Off The Beaten Track with Aidan Geraghty and Moewai Marsh

Mya Morrison-Middleton meets up with ringatoi Aidan Taira Geraghty and Moewai Marsh to kōrero about their current exhibition 'Ka kore, Kua kore' at Blue Oyster Art Project Space in Ōtepoti.

In this series, our kaimahi at The Pantograph Punch venture out of the big cities and into the regions of Aotearoa to kōrero with some exciting creatives.

For this Off the Beaten Track interview Mya Morrison-Middleton meets up with local ringatoi Aidan Taira Geraghty (Kāi Tahu, Ngāi Tūāhuriri) and Moewai Marsh (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Huirapa, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Te Wairoa). Aidan and Moewai kōrero about their current exhibition Ka kore, Kua kore at Blue Oyster Art Project Space in Ōtepoti.

These three are all familiar with each other, so the conversation moves easily across topics such as the changed landscape in Te Waipounamu, the new year and how to grow as a Māori artist. Aidan and Moewai naturally flow in and out of using Ngāi Tahu mita, which replaces the ‘ng’ sound with a ‘k’.

Mya Morrison-Middleton: I won’t try to pretend I don’t know you both, but for everyone who doesn’t, can you tell us about yourselves and your art practices?

Aidan Taira Geraghty: My art practice draws on a bicultural narrative, from my colonial whakapapa and Māori whakapapa. It’s my attempt to make sense of life on the fringe. I can specifically narrow that down to my engagement and fascination with graffiti and the tattoo industry. Being drawn to these fringe arts that have been historically ostracised, I find myself mirroring that to the struggles our tīpuna had to face in reclaiming their Māoritanga in the post-war periods of the 20th century. I find a strange comfort in those metaphysical similarities. I draw a lot of inspiration from both, and that becomes the output of my practice.

Mya: Where did you study?

Aidan: I studied at Otago Polytechnic, and completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts in contemporary sculpture at Dunedin School of Art. I studied Graphic Design prior to that, and spent two years at the University of Otago studying Māori, anthropology and religion. All aspects of those learnings feed into my contemporary sculptural practice as a whole. Being able to understand not only my own culture, but other cultures is beneficial. I grew up in Tāmaki, in Glen Innes, moved down to Dunedin when I was 14, and have been here since. I am mana whenua here in Ōtepoti, but I still call Tāmaki my home.

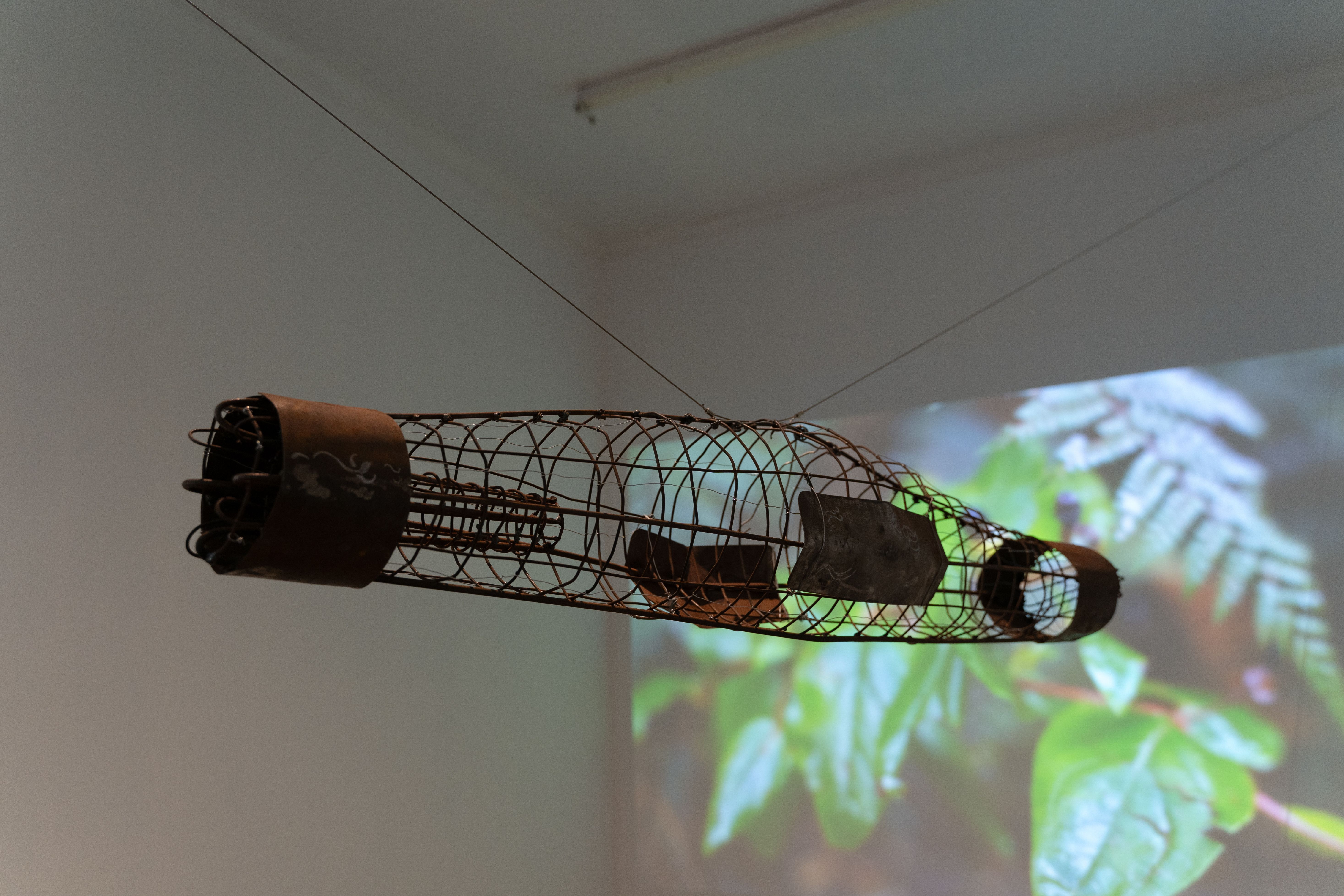

Aidan Taira Geraghty, Matekai, Galvanised and oxidised steel, 2021-23. Photo: Rosa Nevison

Moewai Marsh: Kia ora! I studied for three years and got my bachelor’s degree, also at Dunedin School of Art. I grew up here in Ōtepoti. Alongside that I’ve been studying mahi toi through Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, which has contributed hugely to my arts practice and to my own personal growth within my Māoritanga. My art practice is growing and evolving every year. I’m always learning something new from an artist, a kaumātua, a master weaver, my nan, my colleagues. I’m slowly getting strands of precious mātauraka from special people and that means so much to me as a creative. At art school I majored in painting, and the knowledge I had within te ao Māori was small. I had very few connections and I felt a whole lot of whakamā about myself and my identity. I often asked myself questions like “How can I be a Māori artist?” “How do I make relationships?” I struggled to find what I wanted to express back then, especially because I was fresh out of high school when I started art school. I find institutions to be intimidating spaces, but it did help me grow and learn more about myself. I reflect back on my time at art school often and I feel fortunate for the connections I’ve made since.

When I left art school I started forming connections with my rūnaka and Paemanu [Ngāi Tahu Contemporary Visual Artists]. I began learning more about my whakapapa, getting involved with Māori kaupapa and exhibitions with other local Māori ringatoi. I don’t want to be just a painter, or an artist that only works with earth pigments, because I know what I’m like – I’m a haututū, a day dreamer, and a big lover of creativity, whatever that looks like. That could mean bold colours in a painting, or being on my whenua creating a dreamy earth palette of my landscapes or making paper to mimic the surface of Papatūānuku with materials I can find. Whenua pigments are a part of my practice. I’ve been researching and learning about them and they have been such a huge factor of connectivity for me in my toi, which I really value. There’s still so much more to learn! Te ao Māori is huge. There are so many strands of it I want to explore, and that excites me. I’m eager to learn and create as much as I can and I’ll keep grasping on to knowledge and adding that to my kete. I guess for now you can call me an artist who doesn’t know what she is yet.

Mya: What inspired you both to explore the themes of pollution and protecting resources in Ka kore, Kua kore?

Aidan: In my second year of art school I started trying to create a motif for myself that represents pepeha. Through that I came to tuna, which is the predominant kaupapa in my whānau. We are kaitiaki of tuna for Ngāi Tūāhuriri. My first engagement with my Māori identity was learning how to eel in my ancestral river, the Waimakariri. I’ve watched in real time over the past ten years as a lot of the Waimakariri has been lost to the bovine industry due to farming in Canterbury and overuse of the waterways without any challenge. There’s a lot of pollution run-off in the Waimakariri as a result of that, and it’s sad. So I started making these hīnaki that use farming materials. The first one I made was called Matekai, which translates to ‘deathly hunger’. It was an emaciated hīnaki that wouldn’t be able to catch tuna, it wouldn’t hold. I tried to create a sense of melancholy in my works that reflected my perspective of this colonial industry.

Installation view, 2023. Photo: Rosa Nevison

Moewai: I drew inspiration from the Tūturu series that I created for Paemanu: Tauraka Toi. It was made out of paper using invasive plants, and painted with whenua pigments. That was my first time gathering kōkōwai or maukoroa, and other whenua pigments, from each of the landscapes that I whakapapa to. For this show I wanted to explore another layer of my whakapapa. As Aidan was saying, the materials introduced due to colonisation and disrupting our waterways were an interesting crossover with both of our mahi, so I wanted to create an extension of the work Tūturu, highlighting the damage that is happening in te taiao. I wanted to make more paper works and visit sites that had significance to me when I was growing up in Pine Hill, under Kapukataumahaka, with my grandparents. I spent a lot of time at Bethune’s Gully, and have lived by Ōwheo more or less all my life. Those waterways were significant to me growing up, so I felt strongly about making work that highlights the damage that has been done to them. It was a great opportunity to explore something new with my mahi, too.

Mya: Was this your first time collaborating together? Have you enjoyed it? What have you learned from collaborating?

Moewai: I’ve really enjoyed it.

Aidan: Yeah, me too. The juxtaposition of our works created something larger than we anticipated. From my perspective, my works are industrial, intense and rugged, and they sit nicely against the backdrop of yours, which are delicate and thoughtful.

Moewai: Yeah, I agree. Aidan and I collaborated on the river stones that sit in the corner of the gallery space. The stones reach a descending point in the gallery, with the work coming down off the maunga Kapukataumahaka. Aidan’s hīnaki move their way through the awa, and the paper I made has movement when you walk around the room. It gives a sense of flow, and hearing the sounds of the awa in the video installation makes it feel more alive and robust, too. Eventually the works come down to reach the river stones and the kōkōwai at the bottom. He carved all the eels into them and I painted kōkōwai on top. I feel like the collaboration in our mahi adds to the layers of connections and whakapapa we have to this whenua. I really like the sculptural element that Aidan presents in his works and how he creates them to become taonga. We both acknowledge the whakapapa of the resources, the place that these works connect to and the mauri present within them.

Aidan Taira Geraghty & Moewai Marsh, Tuna Heke, Greywacke, kōkōwai, 2023. Photo: Rosa Nevison

Mya: I love the stones! What do you both enjoy about being artists living in Ōtepoti?

Aidan: The community.

Moewai: Yeah, I’d say the same. We have a unique and diverse community here in Ōtepoti. We’re fortunate that we can be a part of it. This year I’ve seen some mīharo as mahi toi and art events are happening here every month. It’s cool to see more art and creativity being represented in our city by local and Māori artists. There are writing workshops, heaps of exhibitions, new art installations and murals. It’s growing and that’s really exciting.

Aidan: Most people are stoked on what you’re doing. They don’t have to enjoy your mahi, they just like to see the creativity. I’ve got Pākehā mates who don’t understand what I’m making, but they are stoked to see that there’s a high output and such a lovely recognition of toi Māori here. It’s positive. It makes me want to keep making more.

Moewai: Me too. It connects us back to our whakapapa. It’s a real privilege to be making work on our whenua. I feel for people that don’t live on their whenua but are making mahi about their landscapes, or maybe their feelings of being disconnected from home. Whereas Aidan and I, we are home. We’re on our whenua and we get to connect and create with different people all the time. I feel lucky to be able to do that.

Moewai Marsh, Whakaora, Wood shavings, clay, kōkōwai, grass, leaves, bark, recycled paper, rubbish, 2023. Photo: Rosa Nevison

Mya: You’ve both been involved in mural projects and public artworks recently. Can you tell me about those?

Aidan: I was approached by the South Dunedin Street Art Trail to create a mural that represented the pre-colonial history of South Dunedin. The area itself was situated in marshlands called Kaituna, which is all land reclaimed after first contact. Up until the late 1800s there were still kai trails that mana whenua would come inland to use. The mural tries to capture the identity of tuna as a whole, which ties nicely into my work for Ka kore, Kua kore using that motif strongly. I tried to create something that was accessible to everyone. Kaituna speaks to a wider community of people, not just Kāi Tahu, but tākata Māori and tākata Moana as groups represent a decent percentage of whānau who reside in the area. A lot of whānau who are not mana whenua down here don’t have that immediate connection with their whenua, but they can recognise a sense of identity in these motifs.

Moewai: The murals look amazing! I drive past them every day. The kaupapa I worked on is similar to Aidan’s. Last year, I was approached by Ahikā, Aukaha and Dunedin City Council to create artworks to go onto some new recycle hubs being installed on George Street. I’m not going to lie, it was stressful. It challenged how I usually think. I had to approach art making in a different way, because I’m a pen-and-paper kinda gal, so I was experimenting with using Photoshop and using Procreate for the first time.

I was nervous to have my artwork in a public space, because anyone can respond to it. The original design I made, I did not like at all. I was working with Aroha Novak and Simon Kaan, and a week before it was due I changed the whole design. Aroha was like, “Just do it. We’ll smash it out. I want you to be happy with it and for it to represent what’s important to you.” I’m grateful for all their tautoko in making that happen, because the design I did create relates more to my current practice and it does tie into Ka kore, Kua kore. It talks about being good kaitiaki for our whenua and caring about the landscapes that we are in.

Installation view, 2023. Photo: Rosa Nevison

A lot of my practice is about being still. Being gentle with the land, gentle with myself and slowing down. My mahi and my thoughts get messy when I’m not being present. It’s a good reminder for myself and for others to slow down. Good mahi comes with good intentions and taking your time. There are motifs of that in the artwork. I drew a manaia on one side, a tuna on the other side, and Papatūānuku is represented in the middle of the design. They all come together as protectors to take care of our earth. All the colours that I chose connect to different landscapes here in Ōtepoti, where I’ve gathered earth pigments from and that connect me to my whakapapa here as a Kāi Tahu artist. It’s a reminder that we have to be good kaitiaki for the land and take more notice of the beauty that surrounds us. Ōtepoti used to be covered in marshlands and had an abundance of tuna, manu, rākau and plenty of other resources. It’s definitely not as abundant anymore, and many of our waterways are polluted, but that doesn’t mean we can’t look after what we have before it’s gone… ka kore, kua kore.

Mya: A final question. What do you both have planned for the new year? Any Matariki celebrations?

Aidan: I am potentially moving to Wānaka to spend some time there. It’s about time I left the nest for a bit. I’ve got a job opportunity working with my cousin Nikau for Rewi Spraggon, he runs Hāngi Master and might be extending his mahi through there, so keep your eyes peeled. I’ve always been a hands-on person with kai. Kai is my love language. Working as a chef and in hospitality for the past ten years coincides with my art practice. It is awesome that I’m able to use my hands to create something that everyone can enjoy in two different worlds. Being able to supplement my art practice by going off and doing something within the framework of kaupapa Māori is special. That’s my new year.

Moewai Marsh, Hokinga, Single channel digital video, 2:17 minutes, looped, 2023. Directed and edited by Adam Gardiner

Moewai: I’ll be celebrating Matariki at my marae, Puketeraki. I’m going to be staying there for two nights for a wānaka. I’m so excited to be on my whenua, with my whānau, and acknowledge my tūpuna. It’s been a busy and full-on year. We’re all looking forward to having some downtime. We all need it.

I was reflecting this morning on future Matariki, in years to come, and how I can align mahi that I’m working on to not coincide with Matariki. To actually block out time where I don’t do any mahi at all, because it is a time to rest and in the past month I haven’t had much rest. I’m doing it all backwards. This isn’t how Matariki should be. How can I be more intentional? How can I be more gentle? I want to be spending more time with my whānau and friends over Matariki. Doing more wānaka. I just want to hang out with my mates, make art, gather dirt, drink lots of tea and eat yummy kai! I’m moving house over Matariki, too. I’m looking forward to a new beginning, setting up my room and hanging all my mahi toi from all my mates and artists I love on my walls. I’m excited!

Ka kore, Kua kore is on at Blue Oyster Art Project Space, 10 June – 15 July 2023

Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.