Of War And Guilt

Ben Stanley on the passing of his journalism muse.

Ben Stanley remembers acclaimed and groundbreaking war correspondent Michael Herr, and how his influence (and preoccupations) hang over international correspondents to this day.

Though it had been over for more than forty years, the Vietnam War finally ended for Michael Herr last month.

Herr was 76 when he died in the tiny upstate New York town of Delhi on 23 June. He left behind a wife, Valerie. He was a recluse, a writer who hadn’t penned a single published word for many, many years.

I was in Pittsburgh when I heard the news, attempting to write a relatively innocuous sports story. When I did, I put down my can of beer, closed my laptop – and reached into my backpack to pull out the only book that Herr ever wrote.

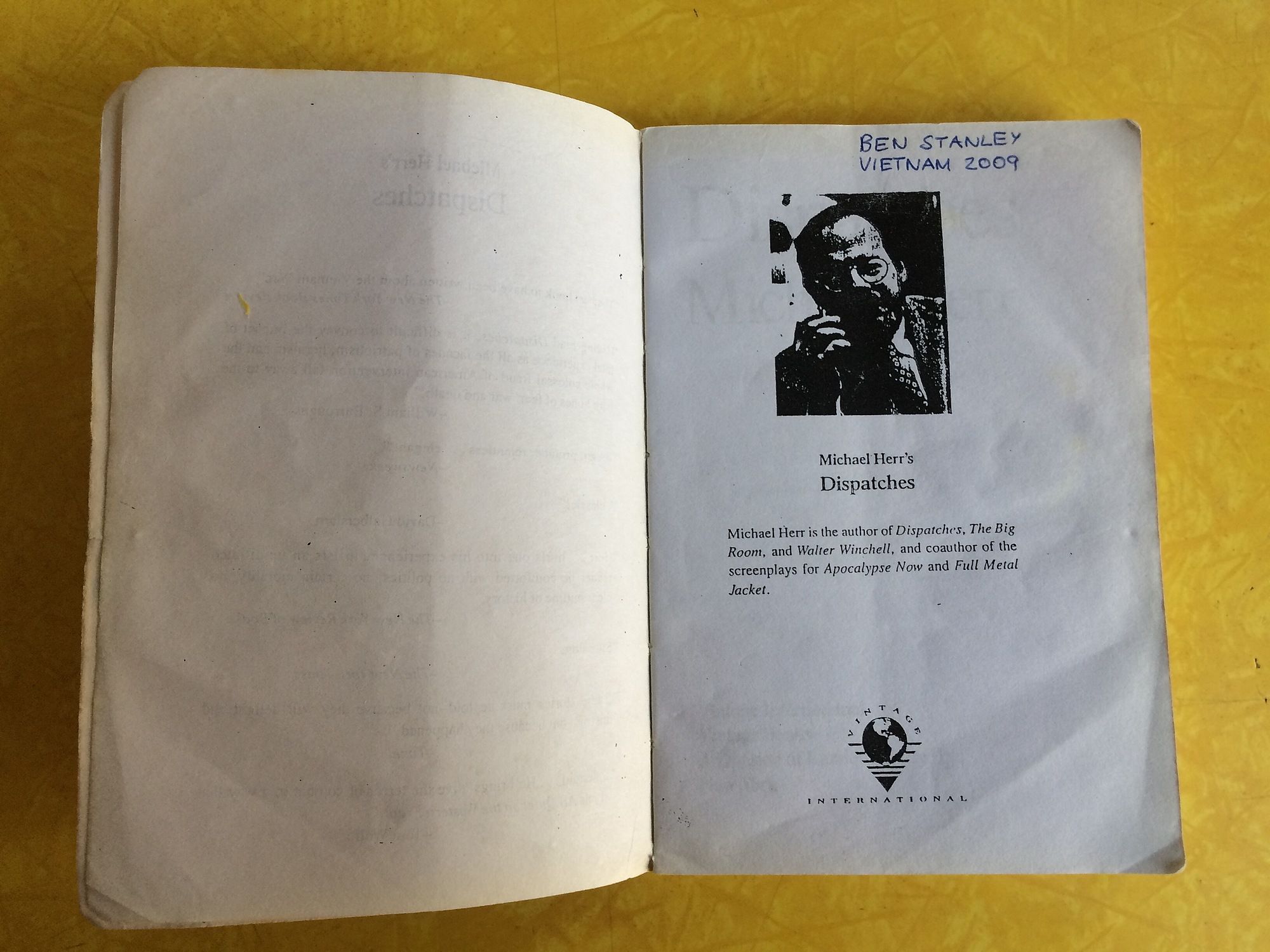

My copy of Dispatches is well worn out by now, as it should be. I have kept it in backpacks, bookshelves, suitcases and carry-ons for nearly seven years. Wherever I had been, it came too.

I bought it from a street peddler in the French Quarter of Hanoi. It was a photocopied fake, the kind of which backpackers to Southeast Asia will be familiar with. Maybe it cost me 30,000 odd dong (around NZ$2), though probably less.

I opened the cover, and there, above a Don McCullin-shot portrait of Herr, I had, in blue ink, penned: ‘BEN STANLEY. VIETNAM. 2009’.

I recognise now what I was trying to do then; trying, in some tiny way, to be part of the ‘Vietnam Experience’, or war as a poet, or war that casts a shadow – dark and mysterious – that I might never fall under.

It’s a typically primal boyhood fantasy that never left me then, or now – but at least it’s one that I’m willing to admit to.

I’ve worn it like a little cross around my neck from the day I picked up the book, if not before. Partly out of pride. Partly out of guilt.

Published in 1977, Dispatches is considered one of the finest books ever written on the subject of war. It is easily one of the best on the Vietnam conflict, and it’s no surprise that over the last fortnight, Herr’s death – and writing - has been memorialised by war correspondents and fellow authors the world over.

From the New York Times to Foreign Policy and all between, the song has remained the same: Dispatches forever changed combat journalism, and the way people have written about war. A paean to futility of it. ‘Herr’s work doesn’t so much loom over contemporary war writing as course within it, a dark ideal and omen all at once,” Matt Gallagher, a former Marine officer and author of the Iraqi War novel Youngblood, wrote in the Paris Review.

Of course, I have no credential to talk about how Herr – the Esquire correspondent to Vietnam when the bulk of Dispatches germinated - influenced journalism. That would be insincere of me. What I can say, very honestly, is what he gave me, and how Dispatches in particular shook me up.

Before Herr’s book, I’d read the other staples of Vietnam literature. The near-mathematical brilliance of Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie and David Halberstam’s The Best and The Brightest. The mysticism of Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. And then: Dispatches.

My first gut reaction felt like listening to the Rolling Stones after listening to Bach or Beethoven. Paragraphs like verses, an entire book like a song, but with a visceral, unmannered intensity.

In Herr’s words, you could feel Vietnam breathe. You could feel the anger, excitement, futility, celebration, disgust and, ultimately, the sad noble defeat of it all.

His language was a fluid, dream-like, informed by the then-counterculture - not caught up on sentimentality or outside meaning – but accepting and embracing the experience, tempering the terror and the exhaustion of the war experience with an irony and rage that bore the mark of his generation. A paean to all faces he saw in the War, and what he saw in the mirror when he got home. Who, and what he kept thinking about.

By Christ, these lines:

‘his face went through about as many changes as a rock when a cloud passes over it.’

Or,

‘Some kept going until they reached the place where an inversion of the expected order happened, a fabulous warp where you took the journey first and then you made your departure.’

Or,

‘You could fly up and into hot tropic sunsets that would change the way you thought about light forever.’

It was a book about the Vietnam War, yes, but more than that: Dispatches was, and remains, a lesson in writing, in language. That’s why I keep it with me.

For a young writer it’s also a lesson in patience and persistence. It took Herr until 1977 to finally get the book out. It sat there in his chest for nearly a decade, passing through a near-nervous breakdown with him, the birth of his child, and then finally manifesting. How painful writing is - that it takes this long - but how undeniably true that it has to. It took so much out of him that he’d never write anything near as significant, again.

“People keep asking me to go and write about war for them,” he told the Guardian’s Ed Vulliamy in a rare interview in 2000. “I say: ‘haven’t you read my fucking book? What the fuck would I want to go and do that for?’ Publishers keep sending me books about Vietnam; I wish they’d stop. I’m not interested in Vietnam. It has passed clean through me.”

But a long gestation had always suited Herr. For Esquire, he had the absolute luxury of not having daily or weekly deadlines, firing off a ‘dispatch’ once every few months from his Saigon Hotel, drunk, stoned and haunted by ghosts. Some journalists struggle without urgency.

Herr embraced it where many others would have blown it. In a war where language was so often a political and military tool, he searched between and behind the lines for true meaning. Of the GIs. The Generals. Fellow correspondents – and, famously, photojournalists Tim Page, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone. He found the language of the conflict, rather than simply repeating sources. That’s reportage in the truest sense.

At one stage, he meets a black paratrooper with the 101st who: glided by and said, “I’ve been scaled man, I’m smooth now,” and went on, into my past and I hope his future, leaving me to wonder not what he meant (that was easy), but where he’d been to get his language. Where he’d been to get his language. Where have all of us been to get our own?

In both these things, Herr revealed to me an undeniable and sad truth that I suspected might be true: that as brutal and disgusting as war was, it was also a true, essential human event that had always existed, and will always exist, and that denying it or convincing ourselves that it can be removed from the pale of human experience is totally, and utterly, impossible.

“If war were hell and only hell, and there were no other colours in the pallet, if that was the essence of the experience, and all that there was to the experience, I don’t think people would continue to make war,” Herr said, in 2001, another rare appearance, this time in First Kill, an obscure Dutch documentary on Vietnam.

As a journalist, I mostly work away on stories about sport and athletes, or profiles on well-known people. I take pride in what I do, and have sacrificed much in the pursuit of it. When I’m at my best, as a journalist, I’m helping other New Zealanders learn a little bit about their world, and maybe making them feel less alone, in that.

But I’ve never covered combat, and perhaps I’ll never truly understand Herr meant when he wrote things like ‘the war made them old. They’d live it out, old.” He was looking in, and out, as he said it.

One of my best mates – also a Kiwi - is a combat reporter. He has spent many, many years in the Middle East, covering pretty much any conflict of note in that region over the last decade. Like Herr, the job has taken an undeniable toll on him.

There is a tiredness that he can’t shake, and a short fuse for small talk and inanities. The vague satisfaction his peers will get in a Mt Eden or Grey Lynn cafe on a Saturday morning, with a flat white and a girlfriend, talking house prices, Brexit or newsroom politics – that humdrum comfort has been lost to him. Yet he remains one of the most noble, principled people I’ve ever met; qualities that, somehow, haven’t been distorted by what he has seen.

I’m guilty that I may never earn that level of honest perspective, and, on a certain level, embarrassed that, I might not ever have the courage to. But then again, I’m sorta glad I haven’t tried. That I never gave in to those foolish, irresponsible elements in me, and headed to the frontline, or close enough that, eventually, I’d be engulfed by it.

Instead, those impulses lie quiet and dormant while I write sports stories, drink beer and re-read Dispatches, until familiar areas of the map heat up again – villages are razed and young people are sent to war, and within me a sad silent conflict flares up too. How do you summon the courage to do what Herr did, and, really, why? I still haven’t answered those questions. Maybe that’s why I still carry around the book.

On the second-to-last page of Dispatches, Herr laid out his final thoughts on Vietnam, back in New York, cleaning it all out.

‘Hemingway once described the glimpse he’d had of his soul after being wounded. [He said] it looked like a fine white handkerchief drawing out of his body, floating away and then returning. What floated out of me was more like a huge gray ‘chute. I hung there for a long time waiting for it to open.’

You can only hope that when that ‘chute finally opened and floated away, it had become clean and white too, that all the grey drained away long ago. That silence and solitude gave Herr what he needed.

As for me, Dispatches is a troubled blessing – a reminder of everything that greater writing stirs in me, and a reminder of its possible toll. I can’t wait until I can put the book on a shelf, and leave it there forever. Not quite yet, though.