Beyond This Horizon: An Oceanic Feeling

Already a lover of cinema and the sea, Doug Dillaman considers Dr. Erika Balsom's new book and curatorial projects within a wider world of watery imagery on screen.

Already a lover of cinema and the sea, Doug Dillaman considers Dr. Erika Balsom's new book and curatorial projects within a wider world of watery imagery on screen.

I: An Oceanic Feeling, the book.

Here, the ocean and the cinema – united by inhuman animus and a penchant for flux – conspire to dislodge man from his pedestal.

An Oceanic Feeling: Cinema and the Sea is the result of Dr. Erika Balsom’s 2017 residency at Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre as International Film Curator in Residence. Officially the first publication in the gallery’s STATEMENTS series, Balsom’s book closely follows the form of Len Lye’s Individual Happiness Now. While the two works are very different – Lye’s a manifesto, Balsom’s a five-fingered riff on a motif – they both share a sense of personal idiosyncrasy. Clocking in at 75 pages, including a generous sampling of stills, An Oceanic Feeling covers roughly the same amount of moving-image works, from A Boat Leaving The Harbour (1895) to .TV (2017) to Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) to Kevin Reynolds’ Waterworld (1995). In the closing filmography, Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) nestles next to Balikbayan #1 Memories of Overdevelopment Redux III (2015) – perhaps the only time they’ve shared space anywhere.

Balsom argues that the ocean has principally been defined as negative space that divides us, and devotes her text to a counterargument, exploring five themes illustrating how the ocean connects us. I’m not fully convinced that the ocean as negative space is the principal way it’s perceived, regardless of what Roland Barthes says – and, indeed, our own Lana Lopesi makes clear that this is specifically a Western colonial view in her book, False Divides – but no matter, as this is largely a framing device for the meat of the book. Exploring a theme per chapter, Balsom considers how moving image has captured the physicality of water, the mystery of undersea creatures, the work afforded by the sea, the lacunae around slave ships, and the perils of international commerce.

In that sense, the book takes on the character of the personal journal of someone returning from sea, reporting sights they’ve seen that you must conjure for yourself

It’s worth noting that Balsom is both an academic – a senior lecturer in film studies at King’s College, London, to be precise – and a critic for film magazines such as Sight and Sound and art publications such as Artforum. This attendant breadth of knowledge, unleashed in a book untethered from the traditional expectations of either academia or specialist audience outlets, permits a dizzying and thrilling chain of association, moving from, for example, the computer-generated waves of Moana (2016) to What the Water Said (1997-2007), a 16mm film made by placing unexposed stock in crab traps in the ocean, in a matter of two pages.

Those curious to see What the Water Said won’t find it online. Nor will they find Hydra Decapita (2010), Atlantiques (2009), Blue Mantle (2010), or many other works that Balsom references. In that sense, the book takes on the character of the personal journal of someone returning from sea, reporting sights they’ve seen that you must conjure for yourself. (Ironically, Tacita Dean’s The Green Ray (2001) – a 16mm film about a visual phenomenon uncapturable on digital video but visible on film – is online, but so badly compressed that said ray is rendered invisible.)

There is perhaps a contradiction that in a book whose title references unboundedness, its tight page count creates a strong sense of boundedness

Like that imagined explorer, Balsom’s perspective is an individual one, borne of personal experience. An Oceanic Feeling makes no pretence of providing a complete taxonomy – indeed, part of the fun for a cinephile is imagining other directions in which Balsom’s project could extend. For instance, while Balsom dedicates a chapter to the otherworldly nature of undersea creatures, there’s a related but discrete topic left unexplored in the ‘othering’ of the ocean as alien. One might look to Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), where the ocean functions as the alien planet, or to James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), where characters are observed from above in a POV identical to the perspective of a scuba diver and Christmas tree worms are found on land, signifying an alien world. Another route would be to consider the ocean as destroyer, either literally as in The Impossible (2012), or figuratively as in Heal The Living (2017), where a road becomes a giant wave to symbolise an impending car crash.

Some might struggle with how much Balsom packs into a terse word count. There is perhaps a contradiction that in a book whose title references unboundedness, its tight page count creates a strong sense of boundedness. Then again, its transient passage from work to work unfolds like a series of waves. As soon as you get the sense and shape of one, it’s gone, and another follows in its wake.

II. My oceanic feeling.

To recognise the presence and proximity of nonhuman interlocutors, to take account of the interdependence of human and not human life, is to court oceanic feeling.

Erika Balsom

When I go to the ocean, even if I’m fully clothed, I get as close as possible. Beaches are beautiful and all, but there’s a moment when you get close enough so that all land disappears and your field of vision is unbounded water and sky. Something inside me shifts. I don’t know if that’s the oceanic feeling, but it’s my oceanic feeling.

And when the film is just right, I can’t say it’s the same experience as when I go to the sea, but it rhymes

When I go to the cinema, I sit as close as possible without losing the ability to see the full screen without eye-strain. I want to lose the sense of being in a cinema if at all possible. I want to be surrounded by images. I want them to wash over me. And when the film is just right, I can’t say it’s the same experience as when I go to the sea, but it rhymes. Something shifts, my body gets lost in the ebbs and flows of the film. A Ghost Story (2017), Voyage of Time: Life’s Journey (2016), Mandy (2018), Stalker (1979): four films that have nothing in common except that I watched them all fifth row centre at the Civic and they produced this sensation in me.

Of course, I’ve fallen in love with films I’ve seen on a television, even on a laptop. But that moment of physicality in my response, my oceanic feeling, is missing

The feeling is never the same at home. Of course, I’ve fallen in love with films I’ve seen on a television, even on a laptop. But that moment of physicality in my response, my oceanic feeling, is missing. And that’s why I continue to brave the cinema, with its high ticket-prices and unpredictable audience etiquette, while most of my peers have settled for staying at home, immersing themselves in torrents.

For many films, though, it’s not a matter of choice. If you live in Aotearoa, you see them at home, or not at all, particularly when it comes to less-commercial fare. The conventional wisdom is that there’s no market for avant-garde cinema, and as much as I love the New Zealand International Film Festival, the few slots dedicated to marginal programming haven’t been able to make room for recent work by Lav Diaz, Ben Russell, Ben Rivers, Kevin James Emerson, Angela Schanelec, Roberto Minervini or Jodie Mack – and those names are just a sample of the ones I know I’m missing. Which is not to say that the NZIFF should be carrying all the weight, but in Auckland, they carry the bulk of it, with stray underground screenings at Audio Foundation or Te Uru, installations at Te Tuhi, and an occasional deep cut at Academy Cinemas only infrequently popping up on the periphery of the consciousness of most film fans.

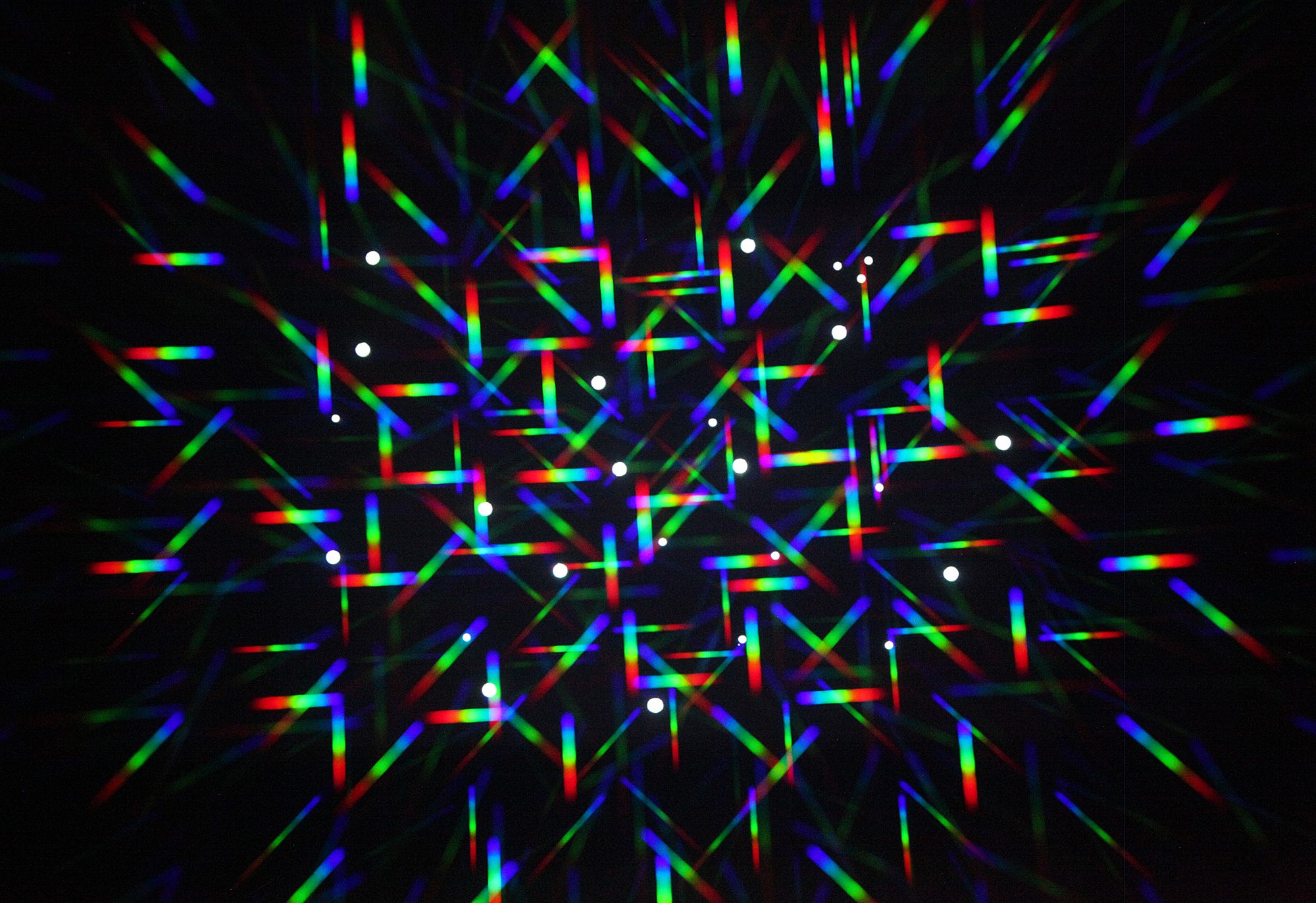

In New Plymouth, it’s a different story. For the past few years, a series of programmes at the Govett-Brewster has been pushing the bounds of moving image art available to civilians. From early series that largely focused on Len Lye’s work (and related moving-image art) or contemporary New Zealand practitioners, the Projection Series has been rapidly growing in both scope and ambition. Earlier this year was their first single-artist contemporary series, focusing on the work of US animator Jodie Mack. As someone who did a road trip down there especially to see her work, let me tell you, it was astonishing. In a programme with no shortage of highlights, Let Your Light Shine (2013), her 3D prismatic work, overwhelmed me with its profusion of hand-drawn lines refracted to surround my field of vision. More than any other of her films, it brought that physical sensation I crave, an out-of-body experience where time slides away.

Now, there’s a new series.

III: An Oceanic Feeling, the projection series.

Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that grey vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

Derek Walcott

An Oceanic Feeling (the projection series) shares a name with Balsom’s book, but they’re more distant relatives than the shared moniker implies. The series is wildly different in scope and focus: ignoring the 19th and 20th century, as well as anything conventionally classified as cinema, Balsom has focused on video artwork produced in the 21st century, mostly in the last four years. As such, An Oceanic Feeling (the book) doesn’t really function as a conventional text for a related series, although all of the works in the series feature in the book.

This betrays the unusual roots of the project. Balsom came to the subject matter in 2014 while on a residency at Fogo Island, Newfoundland, where she was asked to curate a series of films. She found herself more drawn to a writing project related to the ocean, but it floundered for a few years, until she was invited to be Curator in Residence at the Govett-Brewster in 2017.

If curatorial work is a form of advocacy, and platform space is limited, it makes sense to use that platform for both work that you love and work that is unlikely to be seen anywhere else

At first the variant scope of the two projects (the book and the projection series) seems paradoxical, but upon further investigation, it feels increasingly natural. If curatorial work is a form of advocacy, and platform space is limited, it makes sense to use that platform for both work that you love and work that is unlikely to be seen anywhere else.

I would love to report on all eleven works in the series, but the commute to New Plymouth is long and the series is dispersed over several weekends. Thankfully, Te Uru hosted Balsom for her Auckland book launch, and here she screened two of the films from the programme, Sunstone and .TV.

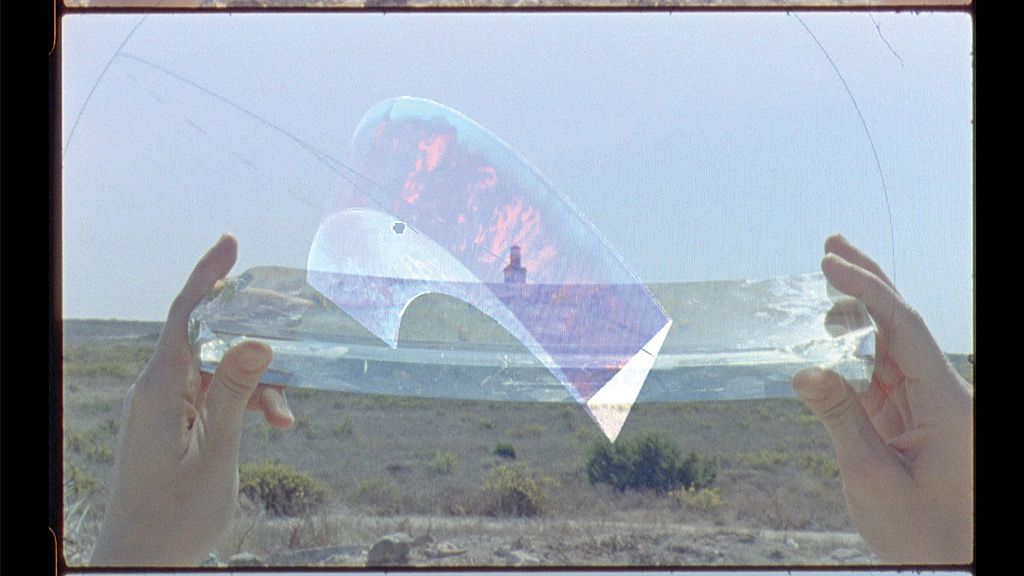

Sunstone (Filipa César and Louis Henderson, 2017) is, from its first shots of the barrier between cliff and sea, a film about edges and connections. It’s about a lighthouse keeper in the westernmost lighthouse in Portugal. It’s about the historic functions of lighthouses and how they work now. It’s a mixture of 16mm grain, YouTube videos of the sea and blunt polygonal digital overlays. There are moments of Len Lye-esque abstraction, but in talking to Balsom it’s clear that, for her, that connection is more coincidental than purposeful.

.TV (G. Antony Svatek, 2017) also deploys YouTube footage, as well as footage from various .tv domains. This domain suffix is owned by Tuvalu, and as onscreen text makes clear throughout the film, it has become one of their main earners. Meanwhile, Tuvalu faces its own all-too-real threat from rising sea levels. But if the country were to no longer exist, would its virtual presence continue?

While .TV asks questions about climate change, it isn’t an issue documentary as such. In fact, An Oceanic Feeling has no room for well-intentioned issue documentaries, in either print or screen form. You won’t find Human Flow, or Blue, or The Cove, or Fire at Sea. The non-commercial forms of Sunstone and .TV, in both aesthetic and duration, position them as entirely something else.

But just how far away are they from cinema, really?

IV. Bridging a gulf.

If your films don’t heal, there’s no point in making them.

Merata Mita

I come to moving image from a cinema background, not a visual art background. But I often find myself drawn to work at the periphery of cinema that I find visually or intellectually compelling – the hand-painted abstractions of Stan Brakhage, the austere haunted spaces of Chantal Akerman, the essay films of Chris Marker, the docufictions of Ben Rivers, the list goes on and on.

You go to a cinema for movies, you go to a gallery for video art. And yet the boundaries are becoming more and more porous

Historically, these exist in a different world from ‘moving-image art’. You go to a cinema for movies, you go to a gallery for video art. And yet the boundaries are becoming more and more porous. Steve McQueen began in galleries before Hunger and 12 Years A Slave became international cinema sensations. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, famous for features such as Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, has taken to museum installations, such as Primitive 2009. Chris Marker moved into gallery work with his Owls at Noon Prelude: The Hollow Men, a multi-screen installation that has been exhibited in both Auckland and Wellington. (And it would be ahistorical to only ascribe this porousness to the present, of course; there is a strong acknowledged affinity between ‘filmmaker’ Stan Brakhage’s abstractions and ‘visual artist’ Len Lye’s work.)

A few days after the Te Uru screenings, I met Balsom in person and asked for her thoughts on this vexing difference, noting the affinities between work on either side of this cinema/visual art divide, and concluding by noting that the audiences were different.

I think you answered your own question. When you look at individual artworks, you think there’s this incredibly creative hybrid space, we don’t need to make distinctions, but there are these two markets. The distinctions are less aesthetic or about practice, and more institutional and infrastructural and economic distinction[s].

Balsom has done much of her academic writing on issues around this divide, including her books Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art (2013) and After Uniqueness: A History of Film and Video Art in Circulation (2017). One distinction she mentioned that made sense to me was that the economics of the art world are controlled by scarcity, while the economics of cinema are facilitated by mass distribution.

We were across from the Ellen Melville Centre, where five moving-image works she had commissioned from New Zealand artists were soon to screen. The curatorial prompt forTruth or Consequences(a project separate from her Govett-Brewster series, presented as part of the annual CIRCUIT Symposium) had nothing to do with the ocean. Instead, Balsom asked the artists for a response to the uncomfortable movement towards a post-truth era. We had a lengthy discussion around her moral belief that it’s important that documentary work in this day and age doesn’t collaborate with the institutions that benefit from a slide away from shared objective truth. (Those interested in detouring deeper into this topic are directed to her essay The Reality-Based Community, presented in Aotearoa at last year’s CIRCUIT Symposium.) Her goal – mission may not be too strong a statement – is to support work that, even if it uses fictive tropes, turns documentary towards an affirmation of truth, instead of a rejection of the possibility of shared understanding.

Perhaps it’s inevitable in a time when the greatest war about reality is whether or not climate change is real that artists would turn to the ocean

Was it coincidental or inevitable that the New Zealand artists selected for Truth or Consequences would prove to be almost as besotted with water as those in An Oceanic Feeling? Either way, from the opening image of Vea Mafile`o’s Toa`ipuapuagā (Strength in Suffering) (2018), water is near inescapable: water quality is an explicit topic of two of the films, and sea passage features in two. Perhaps it’s inevitable in a time when the greatest war about reality is whether or not climate change is real that artists would turn to the ocean.

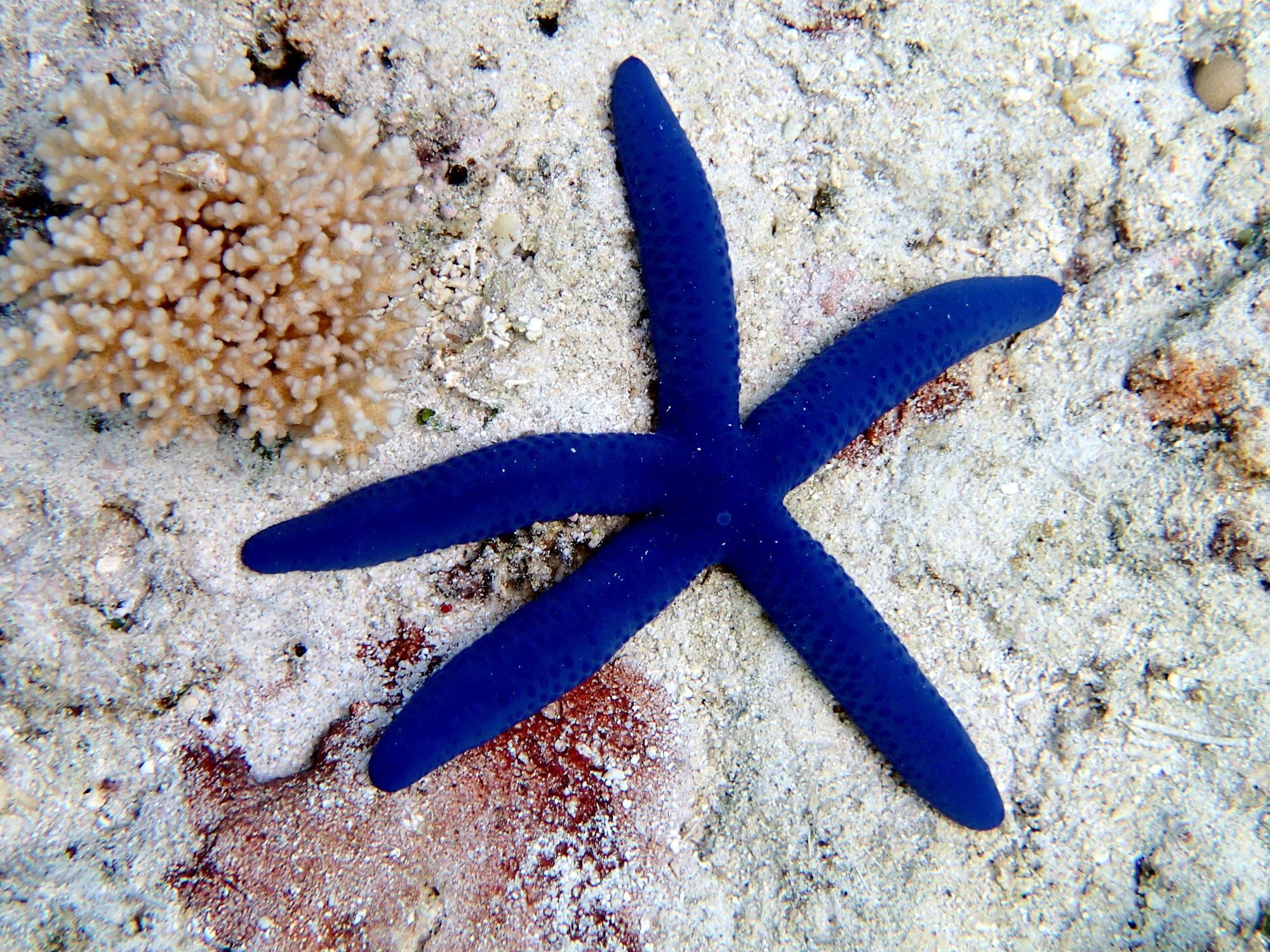

Or maybe it’s just where their inspiration comes from. It’s certainly an inspiration for me. I remember the first time I snorkeled in the South Pacific, and saw a blue starfish, Linckia laevigata, its uneven arms tracing the rocky seabed. If I had known this creature existed before the moment I saw it, I would have spent my days conspiring to find a way to see it. But sometimes you just stumble across sights more perfect than your imagination. Which is why I keep watching new movies, trying new authors, stepping outside my comfort zone.

And at Truth or Consequences, I’m most certainly outside my comfort zone. There are some aesthetic pleasures to be had – I’m always besotted when water appears onscreen, be it in the beguiling reflected forms of Bridget Reweti’s Ziarah (2018) or the shape-shifting split-screen of Janine Randerson’s Interceptor (2018). But many of the chosen aesthetic strategies are highly opaque to me. And as I read Balsom’s accompanying text for Truth or Consequences, which begins with a Jean Baudrillard quote, I’m acutely aware that I am at sea.

No matter how hard I try, cinema is where I feel at home.

V. At home.

A photography of the essence of life itself as the interaction of pulsating and commingling containers.

Stan Brakhage, describing his film Commingled Containers

Stan Brakhage’s Commingled Containers (1997) is a silent study of flowing water, ranging from the close-up to the mind-boggingly micro in a mere three minutes. Brakhage expanded my idea of what film could do, and yet his forceful abstract vision never made its way into the official art world. That it’s not included in An Oceanic Feeling is understandable for many reasons, not least of which is that it’s shot thousands of miles from the ocean.

And yet, it fits, in its own way, or at least with my oceanic feeling. For all of its far-too-brief running time, I’m lost in its beguiling and fresh perspective on water. And I think of the difference between the word, spoken or written, and what it communicates, and the sensation achieved from direct perception. And it’s this that makes An Oceanic Feeling the book and An Oceanic Feeling the series complementary: not just that one gets to see films discussed in the book, but that each medium does something the other couldn’t possibly do.

In a virtual world, what people want is that which cannot be mass produced

Balsom helps run a bi-monthly cinema collective in London, The Machine That Kills Bad People, that pairs features and shorts in unlikely combinations. She notes that “one of the really interesting things that’s happened is that online cinephilia spurs offline activity. London has a really fascinating independent cinema culture, and that is a super important part of what cinema can be and do.”

I put it to Balsom that perhaps this collective experience of cinema-going and experiencing film alongside other bodies ties in with her aforementioned desire for truth as a value, a reality hunger.

I’ve been interested in the resurgence of authenticity as a moral value. In a virtual world, what people want is that which cannot be mass produced. There’s been a renewed interest in collective experience, because it goes against our normal atomised, privatised experience of media.

Tāmaki Makaurau is almost as far away from London as you can get. And yet, even here, murmurs of small passionate curation have come to the fore, with the Academy’s 20th-century women filmmakers programme There She Goes, and the Hollywood’s cult Fridays. And so perhaps there is a space where these disparate films, video art and unclassifiable moving image works that I love can come together, pulsing against each other, commingling, as we immerse ourselves in the light of the screen, in the dark of the cinema, getting lost in something larger than ourselves.

Projection Series #11: An Oceanic Feeling

Curated by Dr Erika Balsom

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

4 August —18 November 2018

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.