NZIFF Week Three, feat. The Red Turtle, The 5th Eye and The Salesman

Doug Dillaman reports back from week 3 of the NZIFF

A film festival is nothing without an audience. Indeed, in the hi-def era, its defining quality might well be the audience. You can curate your own home festivals through VOD or Blu-Ray - even with some of the same films, if you’re into importing and/or VPNs - but you can’t summon the energy or the unpredictability of an audience into your home. Admittedly, it also means you aren’t summoning incessant talkers or mobile device users, although NZIFF’s recent commitment to pre-show warnings means that behaviour seems to be on the wane. (Their slides are also hilarious; I can’t decide if “Don’t annoy our eagle” or the Weiner still suggesting that it’s better to keep your mouth closed sometimes was my favourite.)

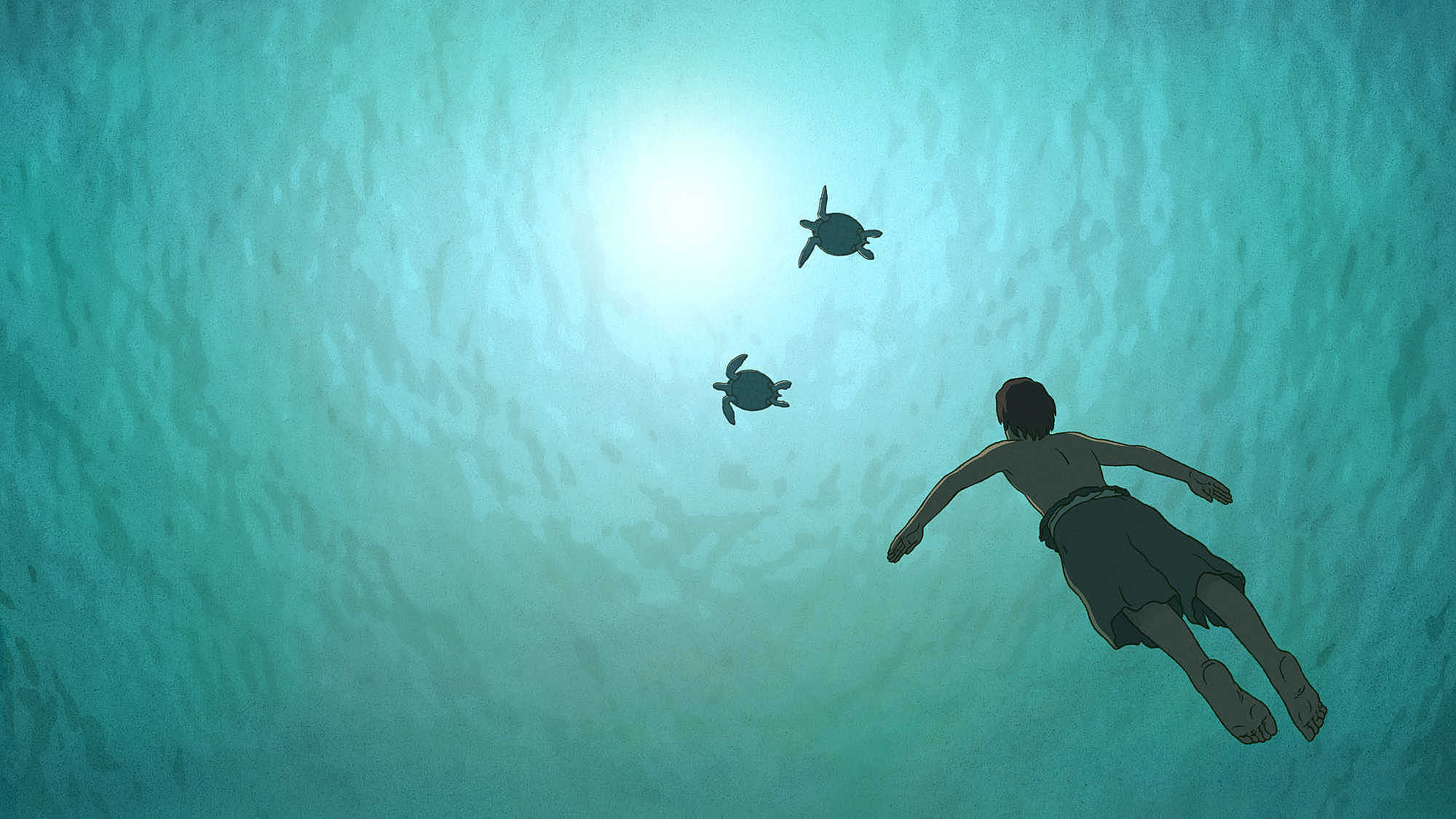

The Red Turtle (Michael Dudok De Wit)

In a crowded, glorious Civic - and if NZIFF had no other reason to exist, the chance to see any movie on the mighty Civic screen would be justification enough - I took a fourth-row seat in the stalls next to a family with two children for Michael Dudok De Wit’s The Red Turtle.

“I remember him!”, the young one, 4 ½, exclaimed when Totoro’s face appeared on the Studio Ghibli logo. But despite Studio Ghibli’s reputation for cuteness, My Neighbor Totoro debuted as a double-feature with the harrowing Grave of the Fireflies, and while The Red Turtle (produced by Fireflies helmer Isao Takahata) isn’t nearly as emotionally eviscerating - few films are - it definitely descends from the less joyous side of the Ghibli family tree.

Now famous as the first European Ghibli film, The Red Turtle starts as a castaway tale that gradually descends into an existentialist nightmare. “Like No Exit, but for kids,” I thought, but it’s not really for kids. Not that it’s particularly harrowing; rather, it’s meditative, limpid, dreamy … or, if you’re the squirmy child next to me, a bit dull.

Eventually, The Red Turtle shifts registers to something less nightmarish, though it never has proper dialogue (a few screams and laughs are the film’s only utterances - presumably no all-star American dub will occur, though it would be a funny joke were it to happen). While a few crabs provide comic relief, the principal attractions are the gorgeous pencil-wash background textures, distinct from any other Ghibli film. The pinpoint eyes also make for non-Ghibilesque human characters: at points, I was reminded more of Toby Morris’ Pencilsword comics than anything else.

NZIFF chose not to include this film in their special kid-centric edition of the brochure, and after a few stray kicks from my intermittent neighbor - he’d crawl upon his mom’s lap, then over to his dad’s lap, then back; those parents did their best, they were saints - it’s clear that was a wise choice. As for adults, it’s perhaps too narratively slight to be fully compelling to most, but for those who are in tune with its feather-light sensibility, swooning may occur.

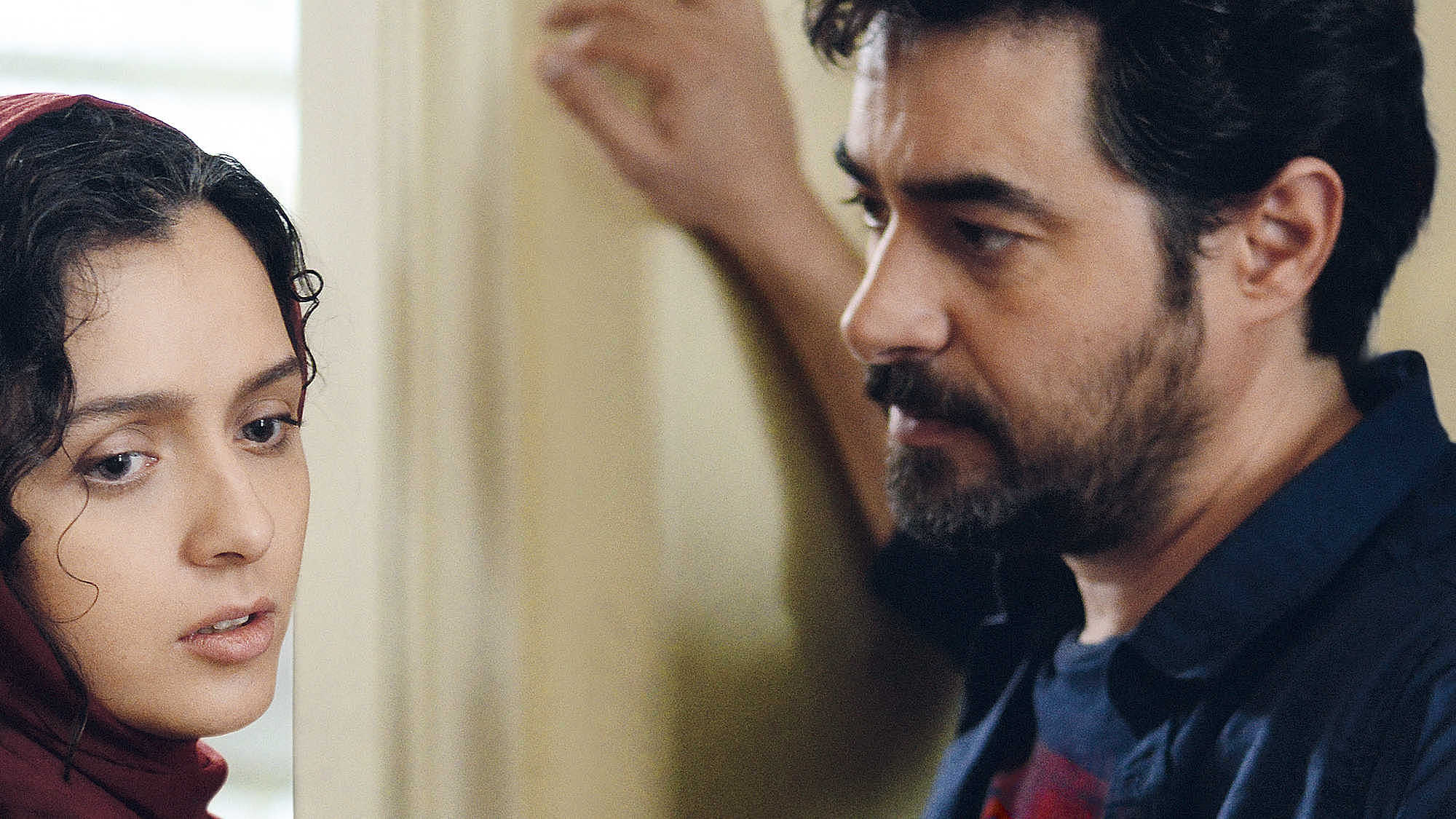

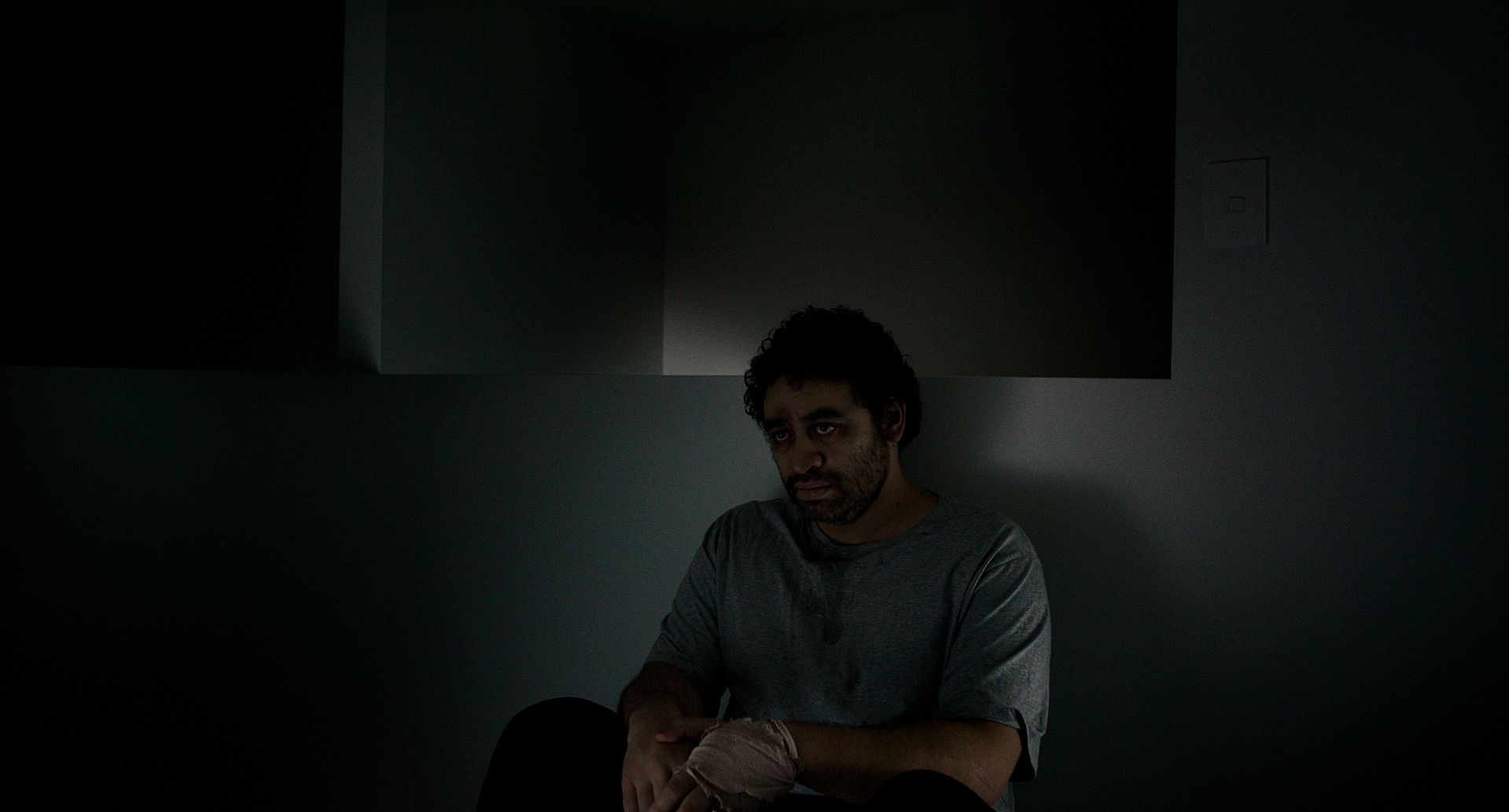

The Salesman (Asghar Farhadi)

At the recently refurbished SkyCity theatre, a capacity crowd turned out for Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman (in some cases absurdly late, an etiquette violation no pre-show slide can prevent). It’s a film of building power, one that raises tension to almost unbearable levels in its final fifteen minutes, by which point I assumed the audience was as one with the film, rapt in its dramatic tension - until two people across the aisle got up and left. I was shocked, though I shouldn’t have been.

After all, I was basically the only person I know who actively disliked Farhadi’s breakout hit A Separation (briefly: I struggle with people yelling at each other all the time, and I struggle with overly constructed plot depicted in an ostensibly realist style: see also Ken Loach, whose well-regarded I, Daniel Blake I avoided with the caution of a peanut-allergy sufferer). Similarly, there are undeniably people who can walk away from The Salesman, perfectly content to remain in the dark about its resolution. And fair enough, though it beggars my mind as to what they could possibly want from a movie.

To back up: The Salesman is about an Iranian couple who are performing the leads in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. A thrilling one-take opening sequence sees their apartment rendered uninhabitable, which leads them to move into their director’s apartment rental, once inhabited by a woman who left her possessions behind. They decide to clear out their predecessor’s belongings, and I then braced for what felt like an overly telegraphed, inevitable confrontation with the last tenant.

This is not what happens, and to share how things really pan out would be impolite. What I can say is that with The Past and now this film, Farhadi has succeeded in winning me over, as his writing skill as a dramatist is matched with his staging skill as a director (although his obsession with mirrors and houses with glass inside is starting to feel like a tic rather than something profound).

Shahab Hosseini, who played the husband in A Separation, particularly shines here as he attempts to navigate increasingly murky moral waters, but the entire cast is strong, and there are more than a few laughs along the way, showing an increasing commitment to a fully textured dramatic style. Most of the Farhadi fans I talked to put this a shade below his previous two or three films: perhaps the repetition of performances of the play-within-a-film strives for a profundity in its parallels to the main action that isn’t quite earned, or perhaps the dramatic scaffolding is a trifle too obvious for some. Nonetheless, a theatre full of people didn’t care about such quibbles by the time the ending kicks into full gear. (Well, except for two.)

Doglegs (Heath Cozens)

Over at Event Cinemas on Queen Street, a disappointingly light crowd turned out on a rainy Thursday evening for Heath Cozens’ Doglegs. I’m not being sarcastic when I say that I expected a documentary about “superhandicapped” Japanese wrestlers to rake in the crowds, particularly with the director present. But with so many films programmed at NZIFF, some films get lost in the mix, and at least in Auckland, Doglegs seemed to slide past many viewers, which is a damn shame.

Doglegs is an account of a group of Tokyo wrestlers - arguably performance artists - who have various disabilities, none of which prevent them from bringing their finest wrestling chops to the public. There’s something intrinsically confronting about a 40 kg wheelchair-bound man taking to the ring, outside of his wheelchair, and using his legs to try to grab his wife’s neck and pull her to the ground. Whether this is more confronting than a caretaker challenging a man with cerebral palsy in the ring and calling him a “lousy cripple” is a moral calculus you may not have expected to ever have to engage in. In black and white it sounds reprehensible - but what makes it any worse than the trash talk in a traditional wrestling match?

While Cozens isn’t a completely neutral observer - the soundtrack does gently nudge emotions along the way - generally he stands back with his camera and lets the audience do the decision making themselves, whether it’s in the ring watching painful punches or at home watching an alcoholic member aided in his drinking by his caretaker. The film focuses on the charismatic Shintaro, whose mother issues and love travails provide some lighter textures, but I felt most strongly the emotional underpull of Yuki Nakajima, whose debilitating depression recontextualises our notions of disability.

Doglegs resists easy emotional takeaways, neither going for cheap shocks or emotional uplift, and some viewers may find it hard to know what to make of it as a result. That’s not a flaw, but a positive aesthetic choice: after all, would you trust a film that told you how to feel about something that challenged your taboos?

On An Unknown Beach (Adam Luxton and Summer Agnew)

Under the same roof, a few days later, a gratifyingly large crowd turned up for the final night’s screening of On an Unknown Beach. (Note to Xpressway trainspotters: the titular Peter Jefferies song does not feature, though Alastair Galbraith does make a soundtrack appearance.) It was a smaller crowd ninety minutes later, as I noticed at least half a dozen walkouts: it’s almost as if an experimental documentary that rests heavily on performances and philosophizing by Dead C founder Bruce Russell might be polarizing.

Their loss. For those on its wavelength, On an Unknown Beach is an absolute treasure, an uncommon achievement of intuitive genius and one of our country’s great films. The film brings together three searchers - in addition to Christchurch native Russell, who wanders the damaged city making noise music while considering long-rejected digressions in 17th century thought, there’s an undersea researcher exploring coral damage caused by trawling and a poet undergoing hypnotherapy - all while searching for connections internally. Set amongst various landscapes of ruin, filmmakers Adam Luxton and Summer Agnew have nonetheless made one of the most beautiful films of the festival, its sea-bound footage providing an icy static counterpoint to 2012’s chaotic and heaving Leviathan, the red zones of Christchurch given the respect of architecture.

On an Unknown Beach takes patience, as its purpose and intent gradually reveals itself. To call it glacial, while unfair, gives some sense of the sheer physicality of the experience. (Theatrical viewing is strongly recommended, as it makes very strong use of surround sound.) While the logical brain will make connections as On an Unknown Beach develops, subconscious thought plays an increasing role as well. There are large passages of the film I can’t explain after a single viewing, but it’s made with such confidence that it makes transcendent sense. I hope it earns an audience at forward-thinking festivals outside this country, as it richly deserves it.

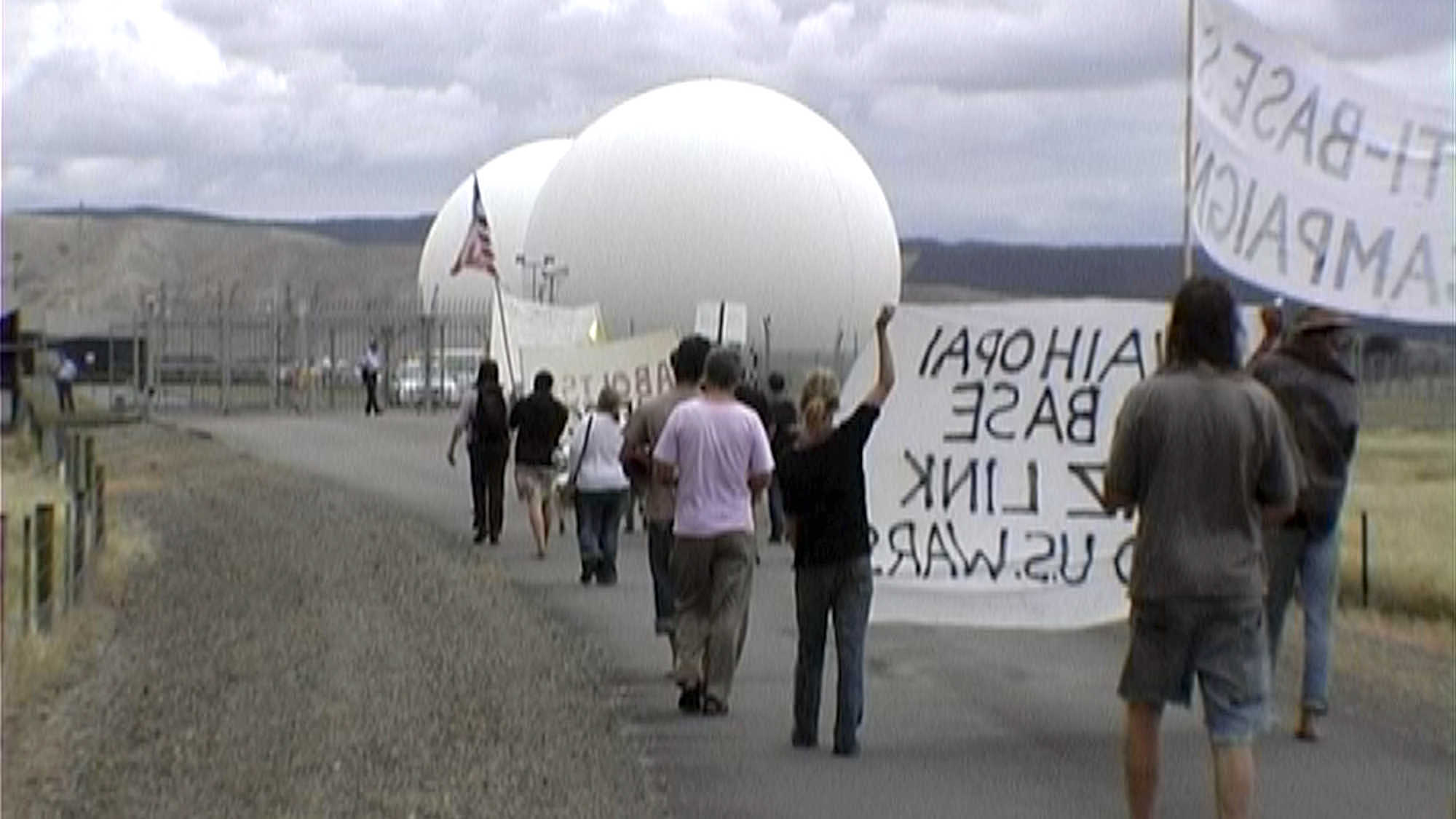

The 5th Eye (Errol Wright and Abi King-Jones)

Entering Academy Cinemas for The 5th Eye, I was handed a flyer for a protest against an international arms fair coming up in November. While tangential to the topic of the film - New Zealand’s encroaching surveillance state and fealty to United States intelligence services - it braced me for what I feared might be a choir-preaching and unfocused left-wing cri du coeur.

Thankfully, filmmaking pair Errol Wright and Abi King-Jones (of Operation 8 fame) are no purveyors of agit-prop. Relying on interviews and copious archive footage, their film is certainly journalism with a pointed perspective, but it is journalism all the same, of the careful, analytical kind that shows their meticulous work ethic. The 5th Eye calmly and clearly lays out the history of the last few years, often letting the perpetrators of the deeds speak for themselves. (Prime Minister John Key’s frequently smug and disingenuous answers in interview footage speak more than an impassioned critique of him ever could.)

What makes The 5th Eye more than just an impressively researched and constructed history lesson is the story of the Waihopai 3, a small group of religiously motivated activists who deflated a dome hiding a satellite dish on a surveillance base in order to call attention to New Zealand’s role in overseas politics.

Their story is sometimes moving, sometimes infuriating, and often just plain hilarious. It’s like somebody snuck Ocean’s Eleven by way of Florian Habicht into an Alex Gibney film, and while it sounds like the mix shouldn’t take, it’s actually precisely the leavening agent the film needs. While The 5th Eye is perhaps a bit long in the tooth in its closing stretch - a recapitulation of Kim Dotcom’s “Moment of Truth” could particularly benefit from a judicious tightening - I’d support making it compulsory viewing for all New Zealanders prior to the next election. (Particularly if they can watch it without the “benefit” of a question and answer session where four successive audience members decide to make a statement rather than ask a question.)

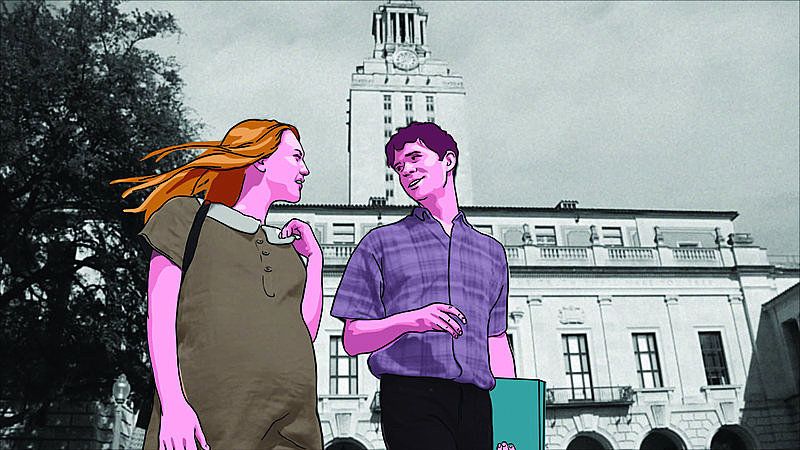

Tower (Keith Maitland)

Where The 5th Eye is sober and calm, Tower throws in everything but the kitchen sink. Film fans might recall Charles Whitman as a name admiringly referenced by R. Lee Ermey's psychopathic drill instructor in Full Metal Jacket. In this present-tense retelling of the1966 University of Texas clocktower shootings, however, he’s an invisible presence for most of the film. The story is embedded firmly with the experience of the survivors - policemen, shooting victims, and innocent bystanders faced with profound moral choices few will ever have to treat as more than a thought exercise: do I run into the firing path of a sniper to rescue a wounded pregnant woman?

You might think that’s enough emotional intensity to drive a documentary, but Tower is just getting started. Combining (often-pixelated) archive footage with the rotoscoping technique popularized in Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly, recreations of the day abound, in varying levels of quality and taste, propelled first by ironic pop music and then a more intense score.

At one point, rock music pounding, spectators running, I felt profoundly uncomfortable: surely this heightened portrait of chaos does more to fuel fantasies than illuminate reality? It’s a discomfort that endured for most of the film, only to dissipate in its final moments as Tower’s moral intent became clear. Most fellow audience members I talked to felt that the end dissipated in energy as well. While I don’t disagree, I feel that giving Whitman’s victims the final word in their own time was also an empowering action, one to keep in mind in a world where survivors so often have their stories drowned out by perpetrators.

Endless Poetry (Alejandro Jodorowsky)

Endless Poetry, the latest film by 87-year old El Topo visionary Alejandro Jodorowsky, has been alternately described as his “most accessible” and “insane”. Both are probably true (although I have yet to see The Rainbow Thief or Tusk). On one hand, compared to the grinding metaphysical screeds of The Holy Mountain (which, to be clear, I adore), this Fellini-esque auto-biopic - installment number two, following The Dance of Reality, and picking up instantly where that film left off - is a straight-up portrait of the artist as a youngish man, not so different from many we’ve seen.

On the other hand, it also involves meat-throwing, nipple painting, piano destroying, intervening stagehands in domestic scenes, interpretive-dance tarot reading off of a nude young man, gratuitous penis sculptures, a dwarf salesman wearing a Nazi uniform, and a sex act whose complete description would get me banned and/or earn me a poetry collection from VUP. And that’s off the top of my head; another viewer could generate a similar yet entirely distinct list.

To surrender to Endless Poetry’s charms requires a certain tolerance for self-aggrandizement, as well as perhaps turning a blind eye to some of Jodorowsky’s more unfortunate tendencies (a recurring plot point has young Jodorowsky rejoicing in not being gay, despite being an artist). And yet, well, I surrender. It takes a special talent to foreground artificiality and have it become a natural surface, yet Jodorowsky makes it look easy.

Entering into the sold-out Rialto screening, surrounded by largely an older audience - who I, perhaps ungenerously, assumed chose the film because of its early Saturday evening time slot and Rialto location rather than any enduring fealty to the director’s lurid genre takes - I predicted mass walkouts and hysteria. Instead, the audience, too, surrendered. One can justifiably scoff at Jodorowsky’s off-camera claims about “psychomagic” or cringe when the self-proclaimed mystic makes inappropriate rape analogies in documentary interviews or encourages incestuous acts on Twitter (seriously), but, as long as the projector runs, he has the undeniable ability to cast a spell.

Spectral Visions (Various Directors)

Back at Academy Cinemas, on the final day, a full house underwent a hypnosis session of its own via the Spectral Visions programme. Five short films by Kiwi filmmakers, linked principally by a commitment to a slow tempo and non-narrative construction, the capacity crowd proved there’s at least a small market for unconventional filmmaking in Auckland, even when up against Pedro Almodovar and Orson Welles.

I’d missed Gavin Hipkins’ Erewhon two years ago, but his latest effort, New Age, is a primal sub-rational invocation, its ritual, intoned passages about the spirit world combining with ruins photography, pottery, and drifting solid color fields to bracing effect. By contrast, I had seen Gabriel White’s Oracle Drive some years back, and though it demonstrated obvious vision and talent, I found it more than a bit maddening. Around the Margins, however, both impressed me and retroactively made me question my reaction to his previous work. Tendencies that read as pretension - particularly in the voice-over delivery and the integration of performance footage - now read to me as puckish humour, and White’s photography of empty lots and McDonald’s in ways to make them resemble alien landscapes can be striking.

Canterbury painter Martin Sagadin used soft-focus and nature photography to dreamy, spaced effect, while veteran Phil Dadson played with dual-screen images of Venetian canals in intriguing ways. The highlight of the program, however, was Alex Backhouse’s Explorer. I’d been invited by the filmmaker to watch a work in progress after writing positively on his previous film (2014’s Unnatural History), but I hadn’t seen the final product, which wisely jettisoned unnecessary plot in favour of atmosphere. Nor had I seen it in a cinema, where the viewer could be entirely developed in an increasingly abstract yet emotionally grounded study of darkened internal spaces, a small house doubling as an entire universe.

It was the most gently captivating textural exploration of half-light and shadow I’d seen since 2011’s Aita. Along with On an Unknown Beach, Explorer was the most exciting local work on display at NZIFF - each straddling a line between conventional form and something more transcendent, voices fully confident yet still capable of surprise - and the festival should be proud of giving such commercially untenable films a platform, and by extension, an audience.

For more of the Punch's film festival coverage, click here.