No Guts, No Glory: NZ's Malaise At The Venice Biennale

Our best chance to get contemporary New Zealand art in the international spotlight comes but once every two years. So why have we given it to someone who left the country over 50 years ago, and what does it say about us?

Though it arguably peaked as a centre of trade, science and intrigue five centuries ago, Venice continues to throw up all sorts of enigmatic questions for a weary but wide-eyed New Zealander. How does Google operate Streetview when it can't fit a van, let alone a moped through the cobbled streets? How does the working population, overwhelmingly based in retail and hospitality jobs, afford to live there? And why has my country decided to represent itself at the 55th Venice Biennale - one of the few truly international opportunities to showcase a nation's contemporary art - with the work of a man who left New Zealand the year my parents were born?

The permanent country pavilions, a constellation of European and other world powers dictated by the vicissitudes of the 20th century's hot and cold wars, were pay-to-view, and I didn't have enough time to do both them and the city a fair deal. Less important or fortunate countries get a myriad of other venues around the city, most of which are still beautiful. So I traced a zig-zag from where I ate my lunch to the Santa Maria della Peita, where my country was represented by Bill Culbert's Front Door Out Back. On my way I would get Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe - as good a spread as any if you don't get to run with the big dogs.

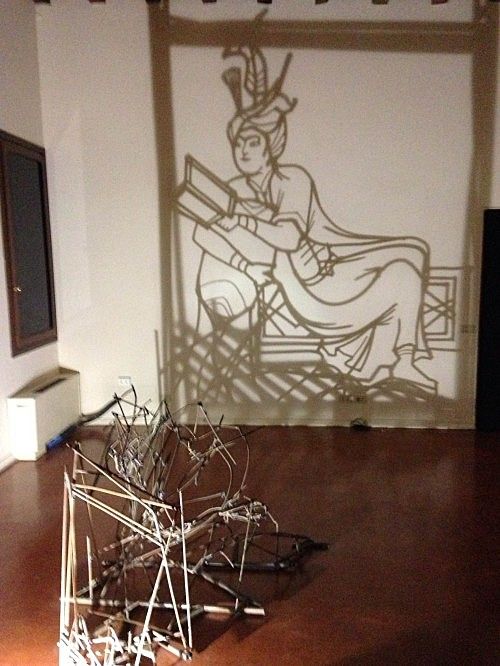

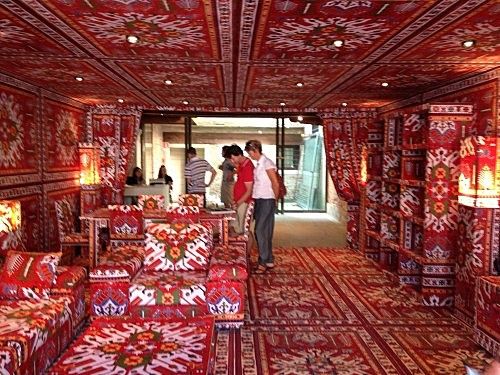

It's also fair to say that none of those countries get a particularly good rap - ravaged by poverty, communism and despotism (still) and not really seen as beacons for any contemporary movement. But here's the thing - they were all tremendous. This year, each country has used their medium-to-small spaces to highlight around half a dozen artists each. Azerbaijan's offerings were tactile and optic treats that beautifully and quietly illustrated the frictions between a very old world and a jarringly new one - photos of a traditional wedding on a digital camera, marshalled together like American prom snaps, a modern middle-class room slathered from the flat-screen down in tapestry carpet, geometric sculptures of extraordinary dexterity that used programmed light to cast ancient iconography.

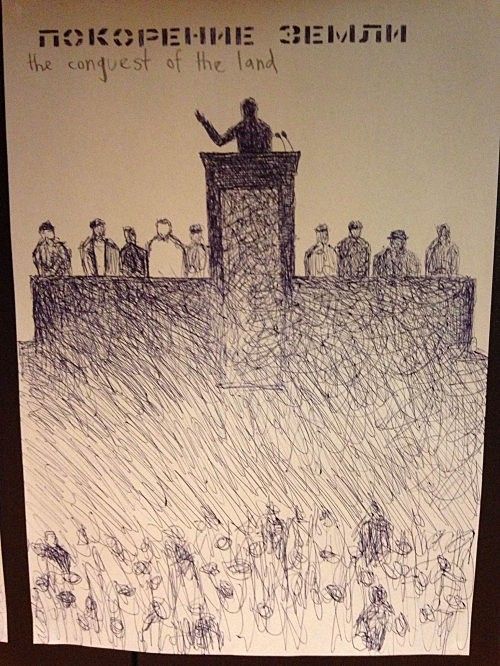

A stone's throw away, the Ukraine, starting with a monument to nothingness in a country that is frantically demolishing a difficult past, failing to offer a future, and freezing citizens in a crushing day-to-day. Here, it was immortalised in the disposable. Hundreds of situations and faces in Biro on paper and matchbox - bad drinks, horizontal depression, and angry young men. Then Zimbabwe, musing on the new expressions of religious belief that emerge after three decades of Mugabe and the political and economic torment that entailed. There are playful cargo cults; there are paintings like confession, so personal and so directed toward another and more spiritual recipient that you want to look away.

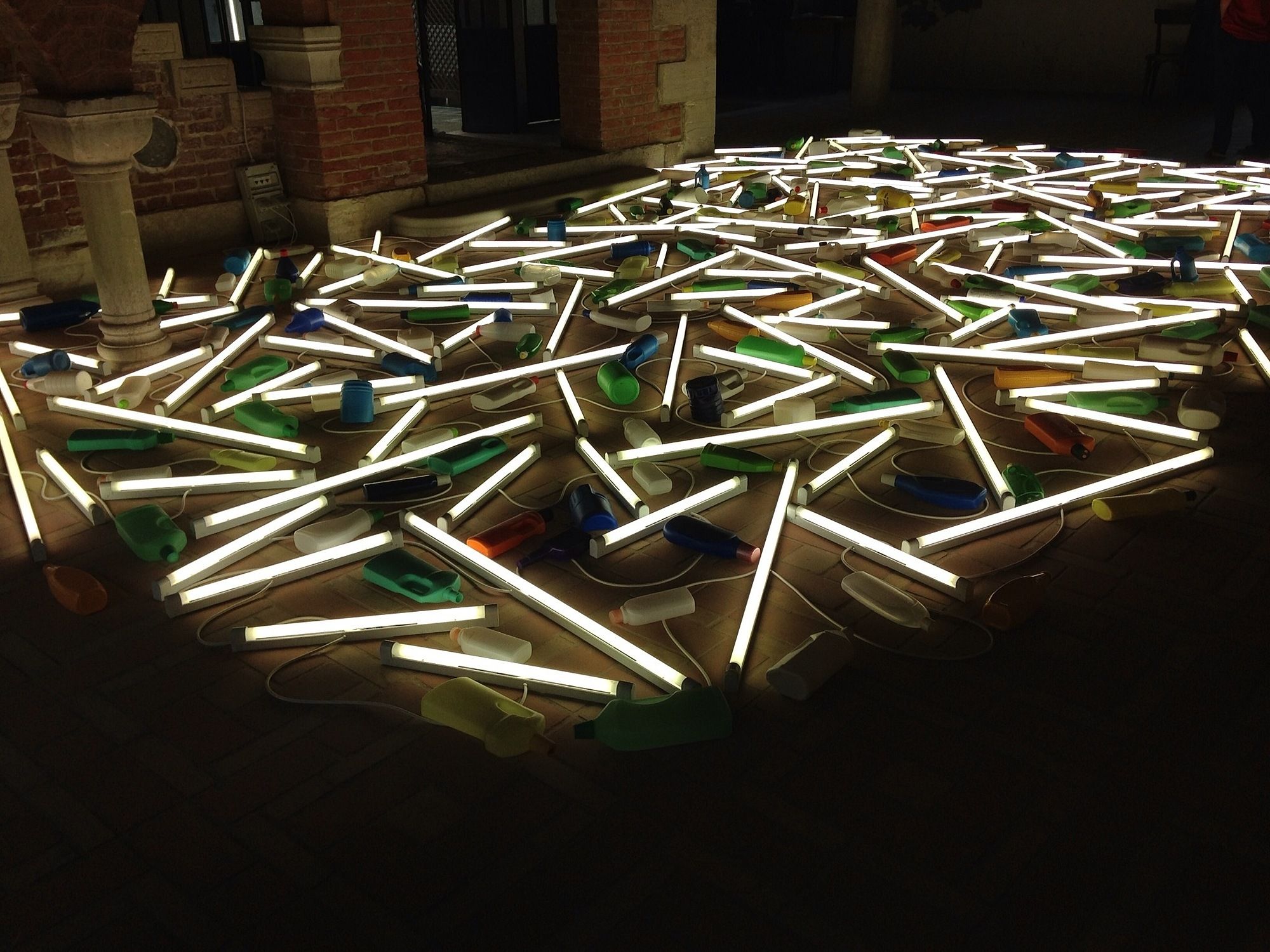

Compared to these, coming to Front Door Out Back is an exasperating sigh that augurs a nagging concern. Culbert welcomes us with halogen lights thrust through antique cabinets, furniture, bric-a-brac, scattered askew in a sea of plastic detergent bottles. At one point, the same lights thread through the new opaque Anchor milk bottles. If there's meant to be a humorous frission of local recognition, it's an awfully small one. To an international audience, it's the equivalent of fronting up at the Edinburgh Fringe, blowing on a pie, exclaiming 'Nek Minnit', and expecting a five-minute standing ovation.

The copy handed out to visitors makes some oblique statements about how Culbert's collection is reflecting on Venice, a city you can probably adequately reflect on while there by stepping outside. Worse, his HUT (2012), ensconced in La Peita's courtyard, is a spare shack of yet more neon tubes that purports to be 'for Christchurch' and the makeshift life its brave citizens have to endure. This is particularly galling, given that Cantabrians haven't just been creating shelters in a practical but artless sense - they've made installations and spaces addressing the post-quake environment that literally fill a book. None of their work is on display at Venice.

This is not all to simply pile on Culbert. Dividing his time between London and the south of France he's sustained an enviably long and enduring career. To produce still at 78 is to be admired, and light is always nice to look at - this is the sort of attractive thing that deserves to accumulate beautifully in the corner of some mercurial millionaire's home when you turn off the pool lights. But these are also the things that damn the administrative choices made - the sheer hubris - to bring this to Venice and say it's ours.

Which is to say: Culbert's established and careful permutations are by definition less contemporary than new practice by younger artists. And while New Zealand can't simply cut off its diaspora and set an arbitrary point at which its expats no longer speak for it, Culbert packed his bags in 1957. Visiting exhibitions aside, his New Zealand is gone, leaving Front Door Out Back to float tepidly and tastefully, with no historical and social context - no Aotearoa - to make an outside audience learn, work or stir. Sitting next to the showcase room of our newest FTA partner, Taiwan, it begins to feel more and more like a trade expo. There's no dirt and no hassle. Ema Tavola spoke on this very website last week about curation that inspires no connection, no engagement. We're here, and it's official from the Ministerial thanks on the pamphlet down.

Who do I think should be there instead? It's not for me to say, because the art I encounter is overwhelmingly that from within my circle of acquaintances, and I approach it all as a total layperson. I know it's often good, but I know it's also overwhelmingly white, middle-class and Auckland-centric. Taking the broad sweep is, presumably, what well-paid and well-resourced administrators should be in their positions to do. I suspect previous Biennale artists like Francis Upritchard (2009) and Michael Parekowhai (2011) come closer demographically to what an introduction to contemporary NZ art might look like, but one or two-artist showcases are both uneconomic and a denial to the forms of collective practise which a number of NZ art communities take pretty seriously. Even our Olympic mentality doesn't warrant mounting a one-man stand, so why should an art show?

For various reasons - some empirical, some subjective - we have a real habit in New Zealand of keeping up with the Joneses. In this little rat race, countries like Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Zimbabwe are the sort of ones we like patting ourselves on the back for being better than, an endless cavalcade of misplaced Borat quotes and vintage hyperinflation zingers. Yet at Venice, all three beat us out hand over fist for courage, belief in youth, belief in the universality of story and experience, respect for their audience. It's self-evidently in the end product, whether that product is to your taste or not.

More ominously: though these are their official missives to Biennale, these are generally not nice countries to be an artist, a writer, a poet or a journalist in. Azerbaijan hasn't had a free and fair election since 1993. Ukraine's Press Freedom rankings continue to plummet Russia-wards. And at least one of Zimbabwe's biennale artists (Michele Mathison) has escaped to the relative safety and prosperity of South Africa rather than stay and fight for a living in his place of birth. Yet I couldn't help but wonder, putting myself in the frame of a mind of a total outsider: which countries' exhibitions look like the product of open, vibrant societies? And which country's seems muted, neutral to a fault and politically fearful?