Where Are The New Zealanders At Cannes Film Festival?

Twenty-six years after The Piano, Doug Dillaman goes to Cannes and finds that New Zealand films are conspicuously nowhere to be seen.

Twenty-six years after The Piano, Doug Dillaman goes to Cannes and finds that New Zealand films are conspicuously nowhere to be seen.

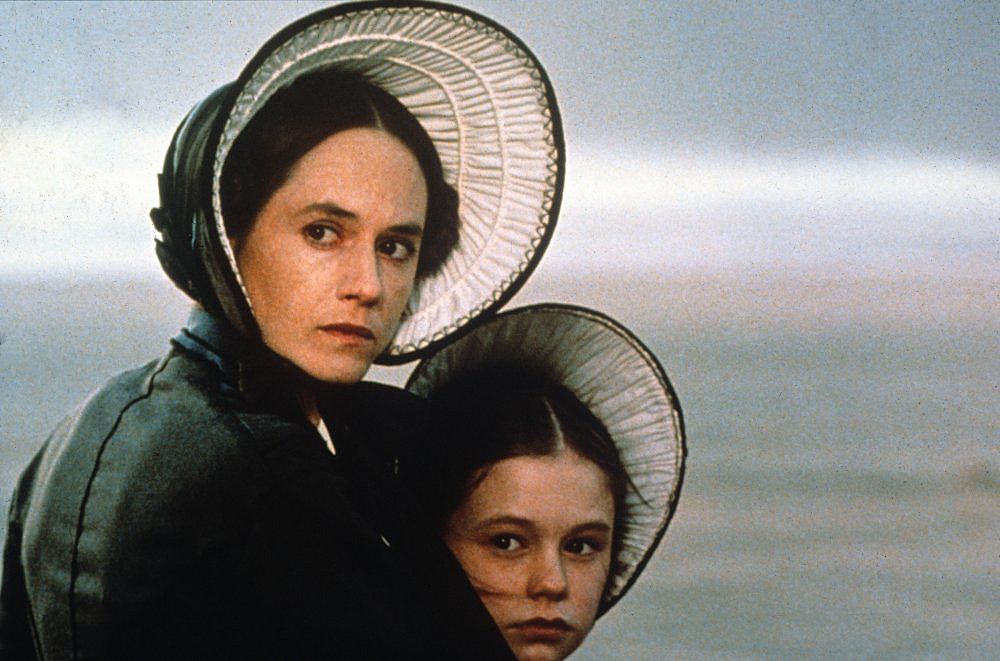

In 1994, no one at Cannes could ignore New Zealand. Off the back of Jane Campion's history-making Palme D'Or victory for The Piano the year prior, 1994’s programme featured not only two short films in competition (Niki Caro's Sure To Rise and Grant Lahood's Lemming Aid), but an entire sidebar of New Zealand short films – only the second time a country had received such an honour. No features were selected for competition, but the market was abuzz over two upcoming films that would premiere later in the year, Heavenly Creatures and Once Were Warriors. After a decade-plus insurgency of Kiwi filmmaking at Cannes – starting with The Scarecrow appearing out of competition in 1982 (Aotearoa's very first representative) and followed in the subsequent decade by feature films Utu, Vigil, Ngati, The Navigator, Crush and 1993’s Desperate Remedies, alongside numerous shorts – the message was clear: Aotearoa had arrived.

Twenty-five years later, where have we gone? The last meaningfully Kiwi film in the Official Selection was Zia Mandviwalla’s short Night Shift in 2012. The Piano remains the last New Zealand film in Official Competition; the only Kiwi feature to screen in Cannes this century is 2001's Rain in Directors’ Fortnight. (For the uninitiated, Directors’ Fortnight is a parallel festival that runs in conjunction with Cannes in a confusing but official relationship, along with other sidebars including Critics’ Week and ACID. There's also Un Certain Regard, which is part of the Official Selection, but not part of the Official Competition.)

For completists, there’s also the Cannes market, which is pay-to-play: Kiwi films Daffodils and Capital in the Twenty-First Century screened there for potential buyers this year. And there’s the low-profile Cinema Des Antipodes, a yearly festival featuring Australian and New Zealand films and marketed to locals. This year featured five Kiwi features, including Waru and both Pork Pies. Good luck spotting any of this on the ground, though. Thousands of films screen in Cannes in late May, and only a small fraction of them are selected for the festival itself. And the ones that are being chosen aren't Kiwi. Why?

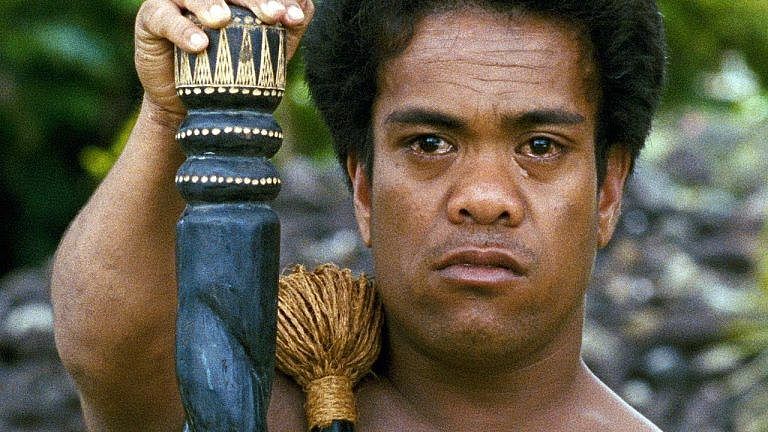

One argument is that Kiwi films these days aren’t good enough to make the cut. And yet, superficially, that doesn't ring true. For one, some legendarily terrible films have made the Official Competition: The Sea Of Trees, The Last Face, and this year's reputed disasterpiece, Mektoub, My Love: Intermezzo. For another, there are some very good Kiwi films with arthouse bona fides. Tusi Tamasese's films The Orator and A Thousand Ropes are as deserving and as strong as this year’s Atlantique. Directors’ Fortnight or Critics’ Week would have suited In My Father's Den and Out Of The Blue. Waru would have been a bold title for Un Certain Regard. You could play this game for a long time.

Another argument: who cares? Kiwi filmmaking doesn't need Cannes to be taken seriously – just ask Taika Waititi or Peter Jackson. Meanwhile, this year has featured high-profile premieres for Vai and For My Father's Kingdom in Berlin, The Chills: The Triumph & Tragedy of Martin Phillipps at SXSW, Come To Daddy at Tribeca, and Bellbird at Sydney. It's hard to argue any of those films would have been better served in France. Cannes isn't the only game in town these days, and after last year's furious flameout with Netflix, which led to Venice snapping up Roma, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and other high-profile titles, some are questioning if it's even the biggest game in town anymore.

Thousands of films screen in Cannes in late May, and only a small fraction of them are selected for the festival itself. And the ones that are being chosen aren't Kiwi. Why?

And yet. It's Cannes. What happens on that red carpet goes around the world like no other film festival. Last year's protest for gender equality made international waves. The walkout at Lars Von Trier’s The House that Jack Built in Cannes 2018 made that film instantly notorious. BlacKkKlansman, meanwhile, went from an unknown quantity by a hit-and-miss director to an electric must-see (and eventual Academy Award winner) after its Cannes opening. And 2019's selection – on paper, at least – was one of the best of the century, with much-heralded newcomers like Mati Diop and Ladj Ly rubbing shoulders with proven quantities like Céline Sciamma and Bong Joon-ho, not to mention titans like Jarmusch, Malick, Almodovar and – oh, yeah – Tarantino.

But New Zealand is nowhere to be seen. So I went to Cannes to find out why.

The opening film of Cannes 2019 was Jim Jarmusch's The Dead Don't Die. I'm a diehard Jarmusch fan, and my opinion, shared by many, is that it's not very good. I saw many films outside the Official Competition that were much, much better. But! The Dead Don't Die has Bill Murray, and Adam Driver, and Selena Gomez, and Tilda Swinton, and RZA, and Chloe Sevigny. And it has a big-name director, one who's been bringing his films to Cannes for 20-plus years. It has red carpet appeal.

The Dead Don't Die embodies the Official Competition ideal: an auteur that functions as a brand, bringing stars that attract flashbulbs from around the world. It's a fitting overture for the 21 films in the Official Competition: a product that sells itself.

At a time when franchises are sucking up more of the box office than ever, a film’s capacity to sell itself is crucial. The Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, James Bond and Disney/Pixar films are safe brand names that guarantee ticket sales. But after that, Game of Thrones (whose finale aired during Cannes and earned more attention on the Croisette than some of the Competition selections) has greater reach than most Cannes films ever will. Serial storytelling is the way of the future, a cleverly-paced series of dopamine hits that guarantees return business in a way that stand-alone feature films can never match.

The only way for ‘arthouse’ product to compete is to provide its own version: auteurs whose latest films act as an entry in a franchise. Perhaps this accounts for the meta-filmmaking elements in The Dead Don't Die (“the next Jarmusch”), or for the preponderance of genre-oriented films in the Official Selection. Auteurs who want to thrive need to join their personal vision to commercial necessities.

The Dead Don't Die embodies the Official Competition ideal: an auteur that functions as a brand, bringing stars that attract flashbulbs from around the world.

Take Romanian director Corneliu Porumboiu. His first feature, 12:08 East of Bucharest, closed with a 45-minute-long live television show micro-analysing the exact moment and location of the Romanian revolution; his subsequent police anti-thriller, Police, Adjective, ended with lengthy recitations of dictionary entries. He's continued with a series of commercially marginal features and documentaries, most of which haven't made it to New Zealand. On paper, his 2019 offering The Whistlers could have played similarly: a corrupt cop travels to the Canary Islands to learn a whistling language so he can speak in code with his collaborators back home.

But from the opening chords of Iggy Pop's "The Passenger", it's clear this is a new Porumboiu, retooled with glossy photography, sexy co-stars, pastel title cards, ready for prime time. Like some other films this year (Jessica Hausner’s sci-fi Little Joe and Arnaud Desplechin’s police procedural Oh Mercy, for two), it’s a departure into a more commercially viable genre. That doesn’t make The Whistlers a bad film; I prefer it to Police, Adjective (though not to Bucharest). But it is clearly the product of Porumboiu’s conscious decision to stop working in the margins and move his brand into the mainstream. It's no coincidence that this is his first film to appear in Official Competition.

So if a crazy Romanian arthouse auteur can make the leap, why can’t a Kiwi?

"We don't shoot our films in winter, so they're not ready at the right time." That was one unlikely, but sensible, explanation offered by New Zealand producer Catherine Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald produced the aforementioned The Orator (which premiered in Venice) and A Thousand Ropes (which premiered in Berlin); she also co-produced That which to come is just a promise, a short film selected for Cannes 2019 Directors’ Fortnight, New Zealand’s only official credit at Cannes this year. It's by Flatform, a European collective, and it's set in Tuvalu. Apart from Kerry Fox's turn in Little Joe, Fitzgerald’s credit as New Zealand producer is the only trace of Aotearoa I'll see on screen in the 29 features and five shorts I take in during the festival. (I’ll get shut out of the new Quentin Tarantino film, missing Zoe Bell's fleeting appearance in Once Upon a Time ... In Hollywood.)

Fitzgerald and I are talking at the New Zealand Film Commission office in Cannes, a first-floor hotel suite near the beach, the night after the big red-carpet premiere, at an event for Kiwis at the festival. The NZFC has flown a fair few producers over here, to support them in their career development and help them make deals with international producers and financiers. I ask some if they’d be willing to share their plans for Cannes on the record, so I can follow up later and find out if they’ve been successful. Generally, they demur. Fair enough: who wants to be known as a producer whose film died at Cannes because they couldn't find a financier?

So instead I ask about why New Zealand films haven't been chosen, not just this year but in general. Some people blame the films. It's significant that no one can name a film that they feel should have played at Cannes. Others point to the focus on making films for the domestic market instead of the international market. One producer points to the lack of name New Zealand actors who can open a film internationally.

Shorts are still taken seriously as an artform in the European market. A great short can build one's brand as an auteur in a way that a slick demo reel can't.

One recurring refrain is the NZFC’s movement away from treating short films as a stand-alone artform to using them as a "development pathway" for features. This change, made back in the mid 2000s under former CEO Dave Gibson, has been successful for some filmmakers. Most recently, Roseanne Liang's Do No Harm worked as a proof of concept for a feature-length version and as a calling card for Hollywood, earning her a job directing an international action feature starring Chloë Grace Moretz.

But it also helps to account for why New Zealand short films – and, perhaps by extension, features – are no longer a fixture at Cannes. Shorts are still taken seriously as an artform in the European market. A great short can build one's brand as an auteur in a way that a slick demo reel can't. Many first-time feature filmmakers in 2019’s various selections have been at Cannes before, with featured shorts.

Even if I have doubts that making a great short uses the same skill set as making a great feature, there's no arguing with the market. It’s the ugly truth: as much as we who make films like to think of our work as pure art, a film that has any hope of reaching the world must be a commercial proposition. Cannes is not a pathway for the exceptions to that rule. It’s a trade show for films that fit that rule.

When I made my first feature, I applied to Cannes. Why wouldn't you? Everybody dreams of going to Cannes, and you've got to buy a lottery ticket to be in the game. In retrospect, lottery tickets would have been a substantially wiser investment.

Here's what I didn't understand: you shouldn't make a feature film and then see where it fits in the market. Unless you're working with the barest of means, you’re investing a great deal of money and time with negligible opportunities for return. When audiences have thousands of hours of streaming content at their fingertips, optimised by professionals for maximum engagement, "good for a first feature" ain't good enough. Hell, even "objectively good" isn't good enough. Anything short of "great, with easily salable elements", and you're screwed. That’s just as true for film festivals as it is for the multiplex.

The biggest predictor of getting into Cannes is having previously got into Cannes.

The cards are stacked against New Zealand filmmakers getting into Cannes for many reasons, but the main one is that the biggest predictor of getting into Cannes is having previously got into Cannes. Many of the features that debut in sidebars have been developed from shorts that previously appeared in those sidebars. More than half of the directors in competition have been there before, and most of those who haven’t have had features in sidebars. Right now, New Zealand has a generation of filmmakers who have never got a short, much less a feature, into Cannes, and without those fish hooks into the system it's unlikely that their next feature will suddenly be embraced by Cannes.

It’s not that we don’t have the talent. One of the best films I saw at Cannes was Fire Will Come, in Un Certain Regard. It's by French-born Spanish director Oliver Laxe, his third feature, a docufiction about a man arrested for arson who returns to his hometown only to – eventually – come under suspicion when a fire breaks out in the forest. It's a very good film, albeit one that will only appeal to hardcore arthouse audiences. But I don't think it's better than Kiwi films like On an Unknown Beach, The Ground We Won, or The Red House. But Oliver Laxe's previous films have appeared at Cannes, so here we are.

When I approached the NZFC for comment on why no New Zealand features have been in official competition since The Piano, I was expecting them to be displeased with my line of enquiry. I certainly wasn’t expecting their initial response, something none of the dozens of creatives and industry professionals I’d met had mentioned: that The Piano is not a New Zealand film, but, rather, an Australia/France co-production.

The existential question of what it means to be part of a national cinema is a loaded one: you would think a film steeped in New Zealand history and indigenous culture, shot by a Kiwi-born director on an iconic New Zealand beach with some of our most famous actors, would be, I dunno, a little bit New Zealand? You’d think the country that fights for ownership of everything from the pavlova to Russell Crowe would put up a teensy bit more of a claim for The Piano. But that’s the way the industrial game works. Capital means citizenship, and so Flatform’s film is more Kiwi than Campion’s.

Capital means citizenship, and so Flatform’s film is more Kiwi than Campion’s.

Cannes is a blinding light, and it blinds those drawn to it from some harsh truths. A total of 1895 feature films applied to Cannes this year; 4240 short films vied for 11 slots in the Official Competition. New Zealand is far from the only country lamenting its absence; Australia was similarly absent, and India, the largest filmmaking production country in the world, has been grousing widely and publicly about its absence. The Official Competition, arguably a showcase for the best in world film, featured only four films with production credits from outside Europe or North America, including Mati Diop’s Atlantique, a co-production between Senegal, France and Belgium. That’s a big chunk of the world left off the stage. Then there’s the pitiful, yet record-breaking, four female directors – out of 21 films – represented in competition.

And in 2019, it turns out, we didn’t have a dog in that fight anyway. According to the NZFC, there were simply no feature films this year that were a) ready for Cannes and that b) all parties involved felt were worth submitting. Which isn’t to say that there wasn’t someone like myself, who submitted without NZFC knowledge. But, to be brutal, if that someone is out there, they never had a chance.

The fact that there were no films to submit to Cannes, of course, implies that it’s not an institutional goal. Are we okay with that? Should we be fighting for a spot on that stage, at a time when the competition is fiercer and Kiwis are increasingly effective at getting their voices heard worldwide in other ways?

I think that the NZFC genuinely wants to do its best in selling each film, and that they fully recognise the significance of Cannes. “Not all films fit all festivals,” says CEO Annabel Sheehan, “but we do always consider the Cannes opportunity and will continue to seek to succeed there.” But selling a film and selling a filmmaker are two different things. And with the NZFC focused on the former, pathways involving the latter – of which Cannes is but one, albeit the glitziest – will only succeed if the filmmaker themselves does the hard yards and understands the business landscape for their art.

This year, the Korean director Bong Joon-ho won the Palme D’Or with his seventh film, the thrilling and powerful Parasite. ‘Director Bong’ didn't make it to Cannes overnight; he’s been on this path since at least 1999. His first two films premiered at the San Sebastian Film Festival. His third film, The Host, premiered in Directors’ Fortnight. His fourth film, Mother, made it all the way to Un Certain Regard. It was only with his sixth film, Okja, that he finally made Official Competition.

The point of recounting that litany is that Cannes can be a long road. For many filmmakers, it might not be the right road. But Parasite is as perfect a blend of personal and commercial interests as any reasonable person could hope for: uncompromisingly caustic in its social commentary, unrelentingly thrilling in its surprises, and 100% what the brand ‘Bong Joon-ho’ has come to promise over the years.

Getting to Cannes in 2019 requires a joining of hands... It takes a long-term commitment to selling an artist and giving them the space to develop their voice.

A talent like Bong Joon-ho’s isn’t generated from thin air by government funding. Even the most dizzying array of funding pathways can only go so far. Individual talents have to be individually nurtured, and so getting to Cannes in 2019 requires a joining of hands between directors with a unique vision and producers with a passion for supporting that vision within the context of a market. It takes a long-term commitment to selling an artist and giving them the space to develop their voice, to let them be distinctive across several stand-alone shorts and feature films. Only then might their name gain the cachet to be that most valuable of commodities: a brand. A Jarmusch. A Tarantino. A Campion!

It also requires filmmakers whose ability to sell their work is as strong as their understanding of the art. Many filmmakers I know – including, historically, myself – have a fundamental fear of the business side of the film business. They want to remain pure, somehow, even while longing for international recognition.

I wish I could send all those filmmakers to Cannes just once. Not just to see the films that premiere and the reception that each gets, but to talk to the industry people they’ll inevitably meet in line. Because, in these conversations, you’re forced to realise that no matter how beautiful and individual your creation may be, it has to fit into a sausage casing to make it to market. And if you don't have the stomach for the butchery, don't expect to be served at the banquet.

Header image: Holly Hunter and Anna Paquin in The Piano (1993, Jane Campion).