What Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Got Right ... and Wrong

Jennifer Ward-Lealand Te Atamira deserves New Zealander of the Year and our respect. But Kiwibank got it wrong when they erased the unparalleled work of Māori artists to revitalise te reo.

Jennifer Ward-Lealand Te Atamira deserves New Zealander of the Year and our respect. But Kiwibank got it wrong when they erased the unparalleled work of Māori to revitalise te reo.

The Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Awards were established 11 years ago by an Australian. It’s PR of course – an opportunity for Kiwibank to connect their brand to pride and patriotism. But plenty of social good is spun from commercial intentions, and capitalist causes still have cultural weight. After all, the Oscars are a junket, but Taika Waititi affirming Indigenous artists as the original storytellers has huge impact. This is culture under capitalism.

I’m proud of Jennifer Ward-Lealand for her win as New Zealander of the Year at the Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Awards for her leadership in the performing arts community and dedication to te reo Māori. One of my first jobs out of Toi Whakaari 15 years ago was under Jennifer’s direction. She’s a leader of grace and determination and for a whole sector of artists, she helps inspire a sense of pride in their work.

Jennifer’s dedication to learning te reo Māori to fluency later in life is inspirational and it’s one more strong, amplified voice adding to mainstream revitalisation of the language. My mum pronounces mānuka correctly because she heard Guyon Espiner say it on RNZ. Another person may have heard what inspired Jennifer to learn te reo and they’ll decide to finally sign up to a class. We can never know all the infinitesimal ways public speakers of te reo help lift the language up for everyone else.

A Māori person learning and reclaiming their reo – a language that was stripped from their tupuna through colonisation – is a political act.

When it comes to te reo Māori and awards, there’s an undeniably political dimension to this conversation which shouldn’t be shied away from. A Māori person learning and reclaiming their reo – a language that was stripped from their tūpuna through colonisation – is a political act. There is also nothing neutral about a Pākehā person who is able spend time becoming fluent in the language without feeling the weight of any shame that comes when a deep part of your identity feels unfamiliar to you. While more speakers of te reo should and must be celebrated, it’s against a history where our settler colonial ancestors learned the language as a tool to dispossess Māori of their land and eventually their tongue. It follows that any Pākehā person winning a significant award in New Zealand in part due to their dedication to te reo, is inherently political, and I think it should be expected that it may gather some critique.

This isn’t about Jennifer or her work. Her award is a deserving achievement. This is about acknowledging Māori histories, especially in the performing arts in Aotearoa, an industry I care about and I know Jennifer does too. It’s also simply about the importance of language in te reo Pākehā. So for the PR company, or the marketing department, or whoever wrote the copy and the press releases surrounding the Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Awards, here are some editor’s notes.

When Jennifer’s win was announced, the framing around it caused some questions on Twitter. This word ‘unparalleled’ kept coming up in the PR messaging in relation to Jennifer’s commitment to te reo Māori in a performing arts context and some questioned it online. Our favourite national condemnation – the accusation of tall poppy syndrome – came crashing in however, and wherever that poppy goes, critical nuance dies.

Regardless, the simmer online brought Jennifer herself to tweet on Saturday, “I have been dismayed that my love for te reo has been overstated into a role that I would never claim for myself. My aroha & respect for Māori revitalising their mother tongue, & knowing it is an intrinsically harder road than mine makes me determined 2 b an ally, mō ake tonu atu”.

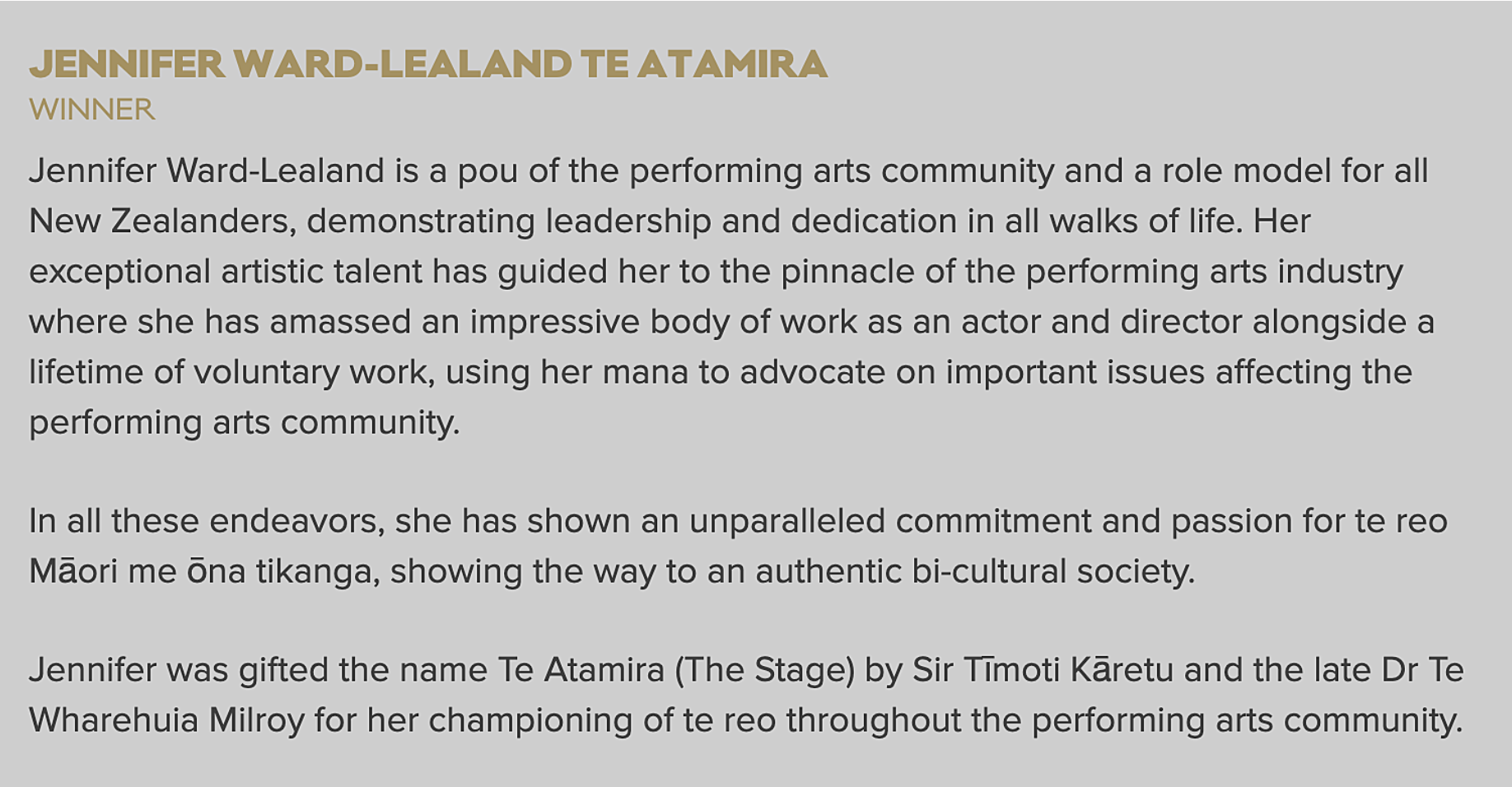

All respect to her. It’s a characteristically gracious acknowledgement, and one that was important to make. So what was that overstatement? It starts with that one word on the winner’s blurb on the Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year website – a word that was subsequently repeated in the media. It’s the kind of word you reach for if you’re writing glossy marketing gush: peerless, unrivalled, exceptional ... unparalleled.

The blurb describes all of Jennifer’s excellent work in the performing arts community then states, “In all these endeavors, she has shown an unparalleled commitment and passion for te reo Māori me ōna tikanga, showing the way to an authentic bi-cultural society” [sic].

The statement was easily taken out of context in the press to mean “unparalleled commitment” to te reo beyond the performing arts, which is, well, madness. In that context, it completely ignores and marginalises the work Māori have done over decades to revitalise their own language.

Even if only in reference to the theatre world, it’s still deeply incorrect. The Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Awards page requires an edit. "Unparalleled", like Old Man’s Beard, must go. It’s tiny, but hugely significant. This is why.

The theatre community in Aotearoa is built on a foundation of strong, connected and vital Māori voices. Seminal Māori theatre company Taki Rua was formed in 1984 and by the mid-90s began te reo Māori seasons at kura kaupapa and marae as well as theatres. Before that, in the late-70s, Jim Moriarty and Brian Potiki formed Te Ika a Māui Players to present Rowley Habib’s The Death of the Land. Hone Kouka emerged from Taki Rua, and with Miria George founded their company Tawata in 2004 to specifically develop and resource Indigenous and kaupapa Māori work. Actor and director Rachel House directed an entirely te reo Māori production of Troilus and Cressida, translated by Te Haumiata Mason, that toured to Shakespeare’s Globe in London. Nancy Brunning directed numerous kaupapa Māori productions, many by fierce te reo Māori advocates, and gave much of her life to uplifting wahine Māori voices.

Elsewhere press releases stated that the winner’s leadership in te reo "increased its use among New Zealand film and theatre for more than a decade". It only takes a glance over the inexhaustive list above to acknowledge that that work has sat with many others for much longer.

Hegemony and privilege are perpetuated through tiny, seemingly imperceptible omissions.

Throughout my career, without a doubt, all of my learning in te reo and tikanga has come from Māori theatre practitioners. I know this would be true for so many of us Pākehā. Toi Whakaari in 2002 was like a shock to the system for a 20-year-old white girl from the Hutt and I learnt from practitioners like Rawiri Paratene, Rangimoana Taylor and Briar Grace-Smith, not to mention my school mates including Te Kohe Tuhaka, Miriama McDowell and Matu Ngaropo. Unlike artforms of more individual pursuit, theatre is communion and ritual, so it lends itself to many aspects of tikanga. Theatre is also, well, life, so for kaupapa Māori practitioners there is no distinction between tikanga as lived and tikanga in the rehearsal room.

I don’t know what an authentic bicultural society is, but I know it doesn’t exist without acknowledging those tangata whenua who Pākehā stole from, who now teach us, and who have fought to uphold their language. In acknowledging the efforts of Pākehā, we must not erase the work of Māori.

Jennifer Ward-Lealand is an excellent recipient of New Zealander of the Year. Advertising opportunities via awards ceremonies are fine – they’re a chance to celebrate genuinely brilliant people doing great things in their communities, affirming their work is important and giving further platform to their causes. But if your brand is celebrating Pākehā in part for their dedication to te reo Māori, you’re not in benign territory. This is our messy history you've waded into, moneybags, and your quick-grab satiny PR copy ain’t gonna cut it. Hegemony and privilege are continued through tiny, seemingly imperceptible omissions. Fix up.