New York to Napier: Tom Gould on 'Skin'

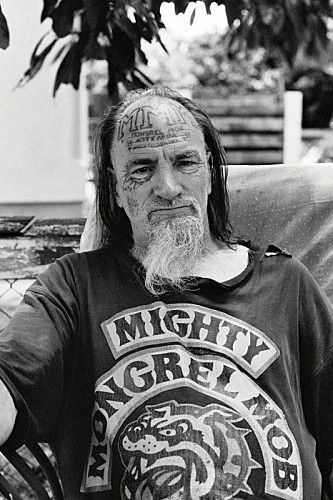

Dominic Hoey talks to expatriate photographer and filmmaker Tom Gould about capturing the moment in a town that's always building over it, jet-setting with Action Bronson, and his powerful short documentary on an upstanding Mongrel Mob member.

At the time of writing, I'm sitting in the Waitakere Ranges, listening to National Radio and breaking up the day by walking my mother’s dogs through the forest. If it wasn't for the odd Instagram photo, and a serious amount of debt, it would be easy to forget that this time last month I was shuffling wide-eyed through the streets of New York.

It was my first visit to the city and from the minute I wandered jet-lagged out of Penn Station, I was struck by its life and movement. The two weeks I spent there are a blur of subways, vegan fast food, drinking, rooftops and art galleries. I found the building from Ghostbusters, performed at the Nuyorican café in the East Village where the modern Hispanic wave of spoken word poetry was pretty much invented, and sought out locations from my favorite Velvet Underground songs.

My own enthusiasm was in slight contrast to everyone I met - from poets, to political activists, to affluent advertising executives - lamenting how the city had changed, how gentrification and a host of new by-laws had left New York a shell of its former self.

Over and over, I was told I’d got here too late. “You should have seen it here ten years ago," people would say about their block, which could mean it was a cool place to party or I might have been shot, or both.

This got me thinking about back home (though I know comparing Grey Lynn to Bushwick is a stretch), how inner-city Auckland has been claimed by the propertied rich, and how I’d wished I had bothered to take more photos before everything was pulled down, modernised, or whitewashed and pastelled over.

Which brings me to New York based and New Zealand born photographer and film maker Tom Gould, who has been documenting two homes for over ten years: his new base in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn and his original haunts in Auckland. Tom dedicates his time to capturing iconic places and people, along with the everyday hubbub of life that surrounds them, before it all disappears.

I first met Tom in 2007, when he took some photos of my tattoos for his zine, The Peeps. Over the next year or so we worked together on a number of different projects and I was always struck by his passion and work ethic. Even in his early twenties Tom seemed to know exactly what he wanted and how he was going to get it. And so in 2009, he packed up and moved straight to New York, where I didn't hear anything from him for a while. Then shoots of Raekwon, members of The Lo Lifes crew decked out in polos and boat shorts, and other well known artists and musicians started appearing on his site. Update after update, it became obvious he hadn't slacked off since leaving our shores.

The last six months have been especially busy, with Tom traversing the globe filming and taking photos of rapper Action Bronson. He's has also finished his first short film, Skin: a documentary about Mongrel Mob member, Martyka “Skin” Brandt who while still active in the gang, has single-handedly raised 10 children, including several as a foster father.

I was lucky enough to watch Skin before sitting down and talking with Tom about the film, his love of photography and whether he thinks New York is still the place to get things happening.

DH- Tom, the movie was dope, very powerful. I was trying to think of a better term but I think that it is what it is.

TG - (laughs) I'm happy to hear that. You’re the first person to see it apart from him (Martyka). It's good after you've spent so much time on something to get it out there.

DH - How long did you spend on it?

TG - I haven't been editing it full time. Its been an on-going project, but I started working on it round Christmas last year so it’s taken about 6 months to get to where we are. I'm pretty happy with the final result. Interested to hear people’s views. I feel the topics addressed in the film are on people's tongues, but it shows a very different side to the gang.

DH - How did you end getting in touch with Martyka?

TG - The whole thing came about because I was leaving New Zealand to come back to the states and I wanted to document New Zealand culture that I found important before I left. Living in the States for so many years and documenting the culture over here, people would always ask whats New Zealand was like. The best way I can ever explain a place is to show people my work, so I felt it was only right to document something important from the country I come from.

I was reading a newspaper article from a local newspaper in Hawkes Bay. The article wasn't about Martyka per se, it was more about the Mongrel Mob starting in the Napier/Hastings region and how they had a bad rep for family neglect and violence and how change was needed. The article mentioned Martyka trying to push fellow mob parents to think about their kids and become better parents.

It described how he was a solo dad of over 20 years that had raised 10 children by himself, 4 of his own and 6 through welfare. This stuck with me and I wanted to speak with Martyka and learn more about his life and see if he would share it with me. I eventually tracked him down, but it took a long time to hear back from him.

Eventually I went down to meet him in Napier over the past Christmas. I didn't really know what his personality was going to be like. People don't open up to someone they have never met face to face over the phone, especially someone with his background, so it was hard to gauge how the film may turn out.

When I went to meet him it was kinda crazy, I still vividly remember first seeing him. I was on my way to Napier and he said to meet me in the National Aquarium car park. So I pull into the carpark and I see him standing by the water smoking a cigarette, dressed in his ridgies, with his Mongrel Mob patch on his back. This was such a strong first image for me, and I made sure we recreated the shot in the film.

I didn't know what to expect at first, but he was an amazing person, man. Full of rich history and still heavily involved in the gang, but with a very positive outlook on things. He had a wonderful family, none of his children are involved in gangs, they're all really stand-up people, which I feel squashes those stereotypes that people get caught up on, that gang members can't raise children.

DH - Marty's a gang member, and a lot of the other people you document are I guess what society would consider outlaws or those “on the fringes”. What is it that attracts you to those kind of people?

TG - I think it’s interesting. It's not like that's all I photograph or document. I still like beautiful things, but I like finding the beauty in things that are often over looked and ignored. I suppose the main reason I photograph people like that or make films about that subject matter is to open up peoples eyes. People can be so sheltered and narrow minded and never really look outside their comfort zone. Theres so much more to see and to learn from people that don't come from the same lifestyle that you may come from. I feel if you can open people’s eyes their mind will follow.

DH - Do you consider yourself part of that lifestyle?

TG - Nah, not at all. Definitly not. I suppose I came from a varied background. I came from a background where I hung out with all sorts of mischevious characters but I also came from a good family so I was able to see both sides you know. The people my dad would hang with were from all walks of life and often crazy characters, then my mum would be hanging out in the art galleries. I think because of that influence in my upbringing I have an open mind and open eyes to all walks of society, which in turn helps me relate to people I meet and allows me to create the art I want to.

DH- At what point when you were growing up in that environment did you start documenting your surroundings?

TG- I was probably about 16 when I first picked up a camera and started taking pictures, I began as a stills photographer. I got into it being a kid that was always hanging around, into graffiti and art, then it just kinda spread from there. When I was about 18 or 19 I had a next-door neighbor who was a great watercolour painter and photographer and he was the one that first taught me about processing my own film, dark room techniques and all of that. He really taught me the power of documenting things, he was 96 as this stage. He had a big influence on me.

DH – Wow.

TG - And he told me that the only way you can persevere anything in your life is through documenting it, and that stuck with me. Everything changes, your friends will change, your surroundings will change, things get torn down, places you used to hang will disappear. So I started trying to preserve that history and freeze time through photography.

DH - At what point did it become serious? Not just in a financial sense, because its kinda your life now.

TG- Yeah I guess it is, and since it’s also what I like to do in my spare time, often I don't even get paid for it. Like this latest documentary, it came out of my own pocket. I just do it for the love of documentation and sharing stories. I suppose it became “serious” when I became serious about it. I've always been a visual person, I was always into art and once you have that eye you always have it.

DH - When you left for New York, what were your goals?

TG - I just wanted to get out there. I was raised on all that imagery of New York: old hip-hop videos, photography, painted subways. Everything I was first inspired by visually came out of that city. I first came out here in 2009 and at that point my goal was just to get here and to take pictures. I was 21 when I arrived, and once I got here I fell in love with the place and the people.

DH - How did you start making contacts with other artists over there?

TG- The first connections I had were all through graffiti. As soon as I came here I was so hyped off being in New York I would never stay home, I was always out all the time meeting people, exploring…and when you're out, like, that that's how you meet people. People love New Zealanders out here, so I got looked after and luckily met the right people.

DH- Do you think being an outsider gives you an advantage when it comes to documenting the city?

TG – Yeah, for sure. I think having an accent is one of the best things. When you're out and about on the streets taking pictures in crazy places and you’re obviously not from here, you’re almost less intrusive because of your accent, you know? Plus people are always going to remember you: “Oh, it's that white kid from New Zealand.” But the biggest advantage I realized is I had a fresh take, a fresh perspective, everything was new and exciting, so I was constantly taking pictures. That’s one thing you gotta seize because you don't have that perspective for long. If you stay in a place you get lazy and you take things for granted - you don't go out and see things like you used to.

DH- Can you talk about working with Action Bronson over the last - what is it? Six months, or a year at this stage?

TG– Yeah, pretty much six months. I actually first meet him in 2009 through mutual friends. He had only just started rapping, he was kinda just joking round, he was a chef in his father's restaurant at that time and we used to go hang there and he would be cooking up crazy things. Around that time he broke his ankle and was laid up in the hospital and started to write what would be his first release. So I started doing some of his first music videos for that project, and it just blew up and he's became really successful. Six months ago, he flew me back to New Zealand for the Rapture tour and we've been on the road ever since. We've been around the world together in the last half--year. As a photographer, it's a dream to get paid to travel the world. And it's great traveling with him cos he's the craziest dude, the funniest guy, constant entertainment. We've traveled to some amazing places: South Africa, all though the States, Hawaii. On another level, it’s also cool seeing your friends succeed, you know?

DH – With all the changes, do you think the idea that New York is the place to make it still rings true?

TG - For sure man, definitely. I feel if you’re talented you can crack it anywhere. Especially 'cause of the internet. Everyone can see what everyone's doing, it doesn't matter where you are. If someone releases an amazing film in Alaska it can get seen in New Zealand the next day. But in New York there's so much more opportunity, there's more going on, more people, more money. I feel like if you get in the right circles and focus on doing good work you get to places that might not be achievable in New Zealand. I love New Zealand and I see myself being back there one day. So many people back in New Zealand are so talented, man. Down there I think there is such a high standard, like a world standard and across the board: music, sports, fashion, art and of course film. For me, personally, I just enjoy being overseas, meeting new people, being around things that keep me inspired. Over here I can walk down my block and see some wild shit and get inspired.

DH – Lastly, what do you have coming up in the future?

TG - Coming up, I've been working on another Kiwi documentary. This one’s based on Las Vegas, the strip club on K Road, and incidentally New Zealand's oldest strip club. That should come out later in the year.

It was another personal project, something I wanted to document before I left New Zealand. That was the first strip club I ever went to, I snuck in when I was like 14 years old. It comes back to what I was saying before about documentation as the only way you can preserve anything; and I really wanted to document that place before it goes or changes. I feel it’s one of the last pieces of that stream of Auckland history, and that particular era of K Road.

Skin was filmed in Napier, New Zealand and edited and directed by Tom Gould, with music by Fire and Ice.

It can be viewed on Vimeo as a Staff Pick right now.