New Horizons, Other Futures: Looking Back on the Blueprint for New Zealand

Alex Mitcalfe Wilson looks back at the Values Party's 1972 manifesto, Blueprint for New Zealand, and compares how the 'future' we occupy now differs from their proposed direction.

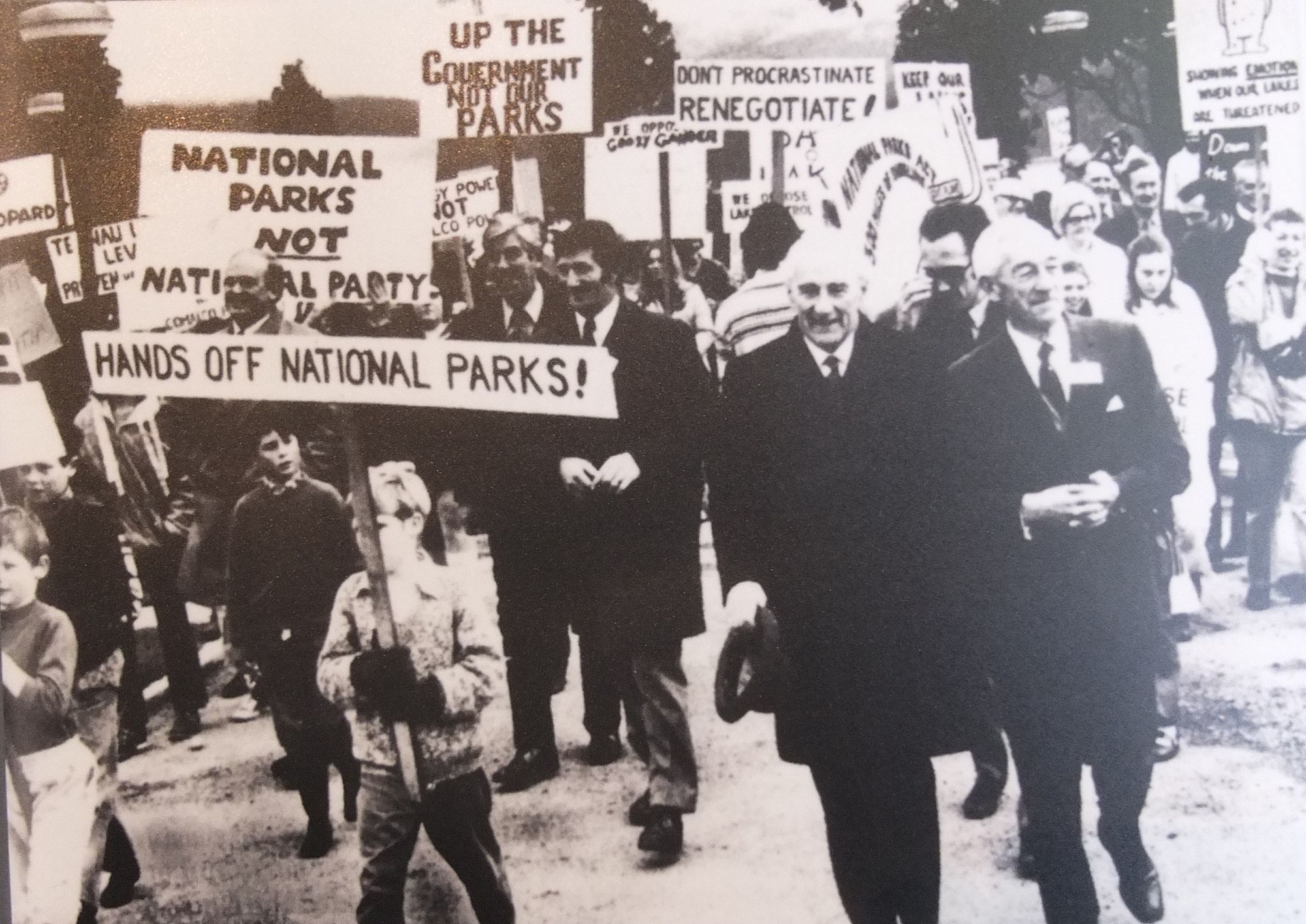

One day, in November 1971, Prime Minister Keith Holyoake’s usual routine ground to a sudden halt. He had flown to Invercargill to celebrate the opening of Comalco’s Tiwai Point aluminium smelter, a major industrial development that was touted as New Zealand’s gateway to a brighter economic future. But, as he stepped from his car at the smelter’s gates, he found himself surrounded by thousands of chanting people, their jeers suggesting that his optimistic view of the smelter’s possibilities was not shared by everyone. New Zealand already had a long, proud history of political protest but this confrontation was the beginning of something entirely new; a movement that centred explicitly on the links between economic development and environmental harm.

The protesters who heckled Holyoake that day were concerned about the smelter’s likely environmental impact, as well as the Manapouri hydroelectric expansion that was supposed to power it. Widespread discontent with both plans had crystallised throughout the late 1960s, when Holyoake’s government suggested raising Lake Manapouri by eleven metres - inundating eight hundred hectares of shoreline forest - to increase its hydro station’s capacity. Sacrificing such a unique landscape to support heavy industry seemed a poor trade-off to many New Zealanders, whose vigorous campaign to save Manapouri would generate a 264,000 signature petition and years of nationwide protest.

The petition, and protests like the one that greeted Holyoake that morning, would eventually bear fruit, with Norman Kirk’s newly-elected government swiftly discarding the lake-raising project in 1972. Their campaign also had the wider effect of illuminating a central bias of establishment thinking that had been taken for granted until that time: that economic development was the main project of government, and environmental integrity an optional extra. Politicians from both National and Labour had been caught short by the public opposition to developments like Manapouri. To most of them, it seemed mad that trees, birds and water could be more important than increasing industrial output and chasing the economic growth that it might bring.

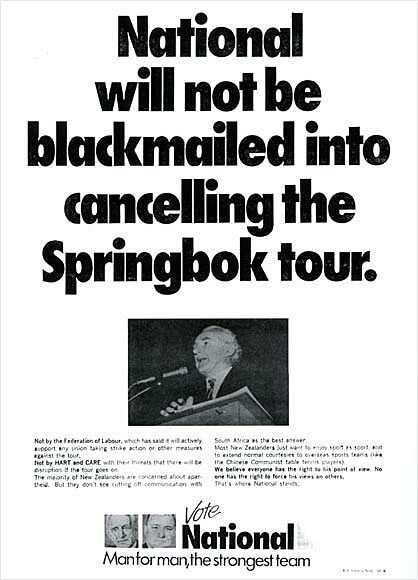

Manapouri was not the only focus for social change by the early 1970s. Alongside an emerging awareness of environmental issues, a growing number of people were concerned with New Zealand’s harsh social realities. As a decade-long economic boom suddenly gave way to low prices for traditional farming commodities, uncertainty and unemployment took the veneer of stability off New Zealand society. Scapegoats were sought by politicians and the press alike, and Māori and new migrants from the Pacific faced pervasive racism. Parochial prejudices also defined our international relations; the National Party’s 1972 election campaign still confidently boasted of their dedication to continued sporting ties with apartheid South Africa.

It was in this harsh climate that a rising generation of young people, more highly educated than their parents and raised in relative wealth, began to look beyond the traditions of earlier generations and seek out new cultural influences from the United States and United Kingdom. This increasing awareness of international happenings - from psychedelic music and recreational drug culture to the Black Panther Party and Women’s Liberation - shed new light on old cultural habits. Global debates on gender, ethnicity, colonialism and sexuality were suddenly audible in a country which had previously valued convention and silence.

At the time of the 1972 election, there were many dark and unspoken corners that these new ideas suddenly threw into sharp relief: New Zealand soldiers were still fighting in Vietnam, nuclear testing continued in the Pacific, identity-based discrimination was ubiquitous and generally legal (particularly for housing and employment purposes), and the effects of racism, colonial oppression and environmental degradation were obvious to those who looked.

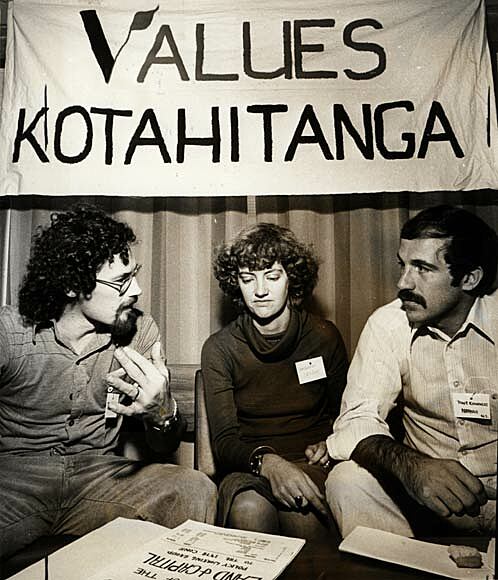

Dissatisfaction with these realities led a significant minority of New Zealanders to engage with the new thinking offered by countercultural and protest groups. In the early 1970s, their energy was visible in gay-rights and feminist movements, nuclear-free, peace and anti-tour campaigns, environmental groups, and a new wave of tino rangatiratanga activists seeking justice for Māori. Though the channels of parliamentary politics remained restricted by a hidebound two-party electoral system, those transformative aspirations were most directly reflected in the newly-formed Values Party.

Looking back from 2014, the Values Party's original platform is still a challenging assessment of our social realities, all the more startling when considered in its context. It’s an unprecedented amalgamation of social justice, conservation, peace and human rights ideals, a document which outlined a path that prefigured future progressive groups of all strains. Although they never won a parliamentary seat, the Values Party would go on to exert a disproportionate influence on political debate, and help pave the way for the Alliance and Green parties.

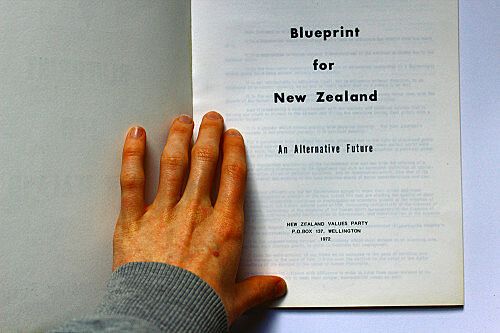

The Values Party often featured in my family’s conversations about politics, pulled out as a reminder that our political history was more than a conflict between National and Labour. They were another intriguing name that fitted into New Zealand’s rich progressive heritage, a story taking in everyone from Te Whiti o Rongomai and Archibald Baxter to the Polynesian Panthers and Native Forest Action. But my interest in them only deepened earlier this year, after I found a copy of their 1972 manifesto, Blueprint for New Zealand: An Alternative Future, in an online bookstore.

The Blueprint is an A4 booklet, fifty-eight pages long, mimeographed and cheaply bound; a humble document with a two-colour cover and a plain buff back. From its first page, Blueprint presents a highly critical study of society and politics in the 1970s, moulded into a radical platform for social transformation.

Its tone is set by a stark opening assessment:

New Zealand is in the grip of a new depression. It is a depression which arises not from a lack of affluence, but almost from too much of it. It is a depression in human values

This contrast between wealth and wellbeing is central to the Values Party’s analysis of New Zealand’s problems. Their manifesto’s main point of distinction from Labour and the traditional left’s assessment of inequality (then or now) is its contention that the visible symptoms of social unrest and environmental destruction inseparable from society’s fascination with economic growth. Rather than proposing ways to mitigate the symptoms of economic disorder, like inequality, inflation or unemployment, the Values Party argued for a society organised on radically different ideals. It was an analysis based on what was possible, and what might be necessary, rather than what seemed simplest to achieve.

Rather than proposing ways to mitigate the symptoms of economic disorder, like inequality, inflation or unemployment, the Values Party argued for a society organised on radically different ideals.

The Blueprint departs from convention at its outset, stating that population and economic growth cannot expand indefinitely. This concept was controversial in 1972, and remains highly contentious today. In place of endless growth, the Values Party asks society to identify a limit beyond which its economy will not grow, a state at which it can continue indefinitely without ruining the lives of its participants, exhausting the inputs it requires or despoiling the environment.

Then and now, it’s hard to understate the extent to which this vision is a total inversion of the familiar political paradigm. Rather than trading off the resources and safety of the future to meet the material desires of the present, the Values Party asked New Zealanders to identify a mode of life that can be sustained indefinitely and to pass up the temptation of individual luxury in doing so. This idea of deliberate restraint echoes the seminal 1972 computer simulation The Limits to Growth, which predicted a collapse in global systems if economic growth was pursued indefinitely.

Although numerous recent studies have reinforced the danger of unconstrained economic expansion, the notion of a steady-state economy remains well outside the boundaries of mainstream political debate. It is not a stretch to conclude that the economic factors that drive commercial journalism in our society contribute to such exclusion, as profit-driven media conglomerates have little incentive to question a state of affairs which privileges corporate growth as a social good.

Having made what seems a fairly intuitive leap - an endlessly increasing population will consume an expanding amount of resources, making it impossible for society to exist within any material limit - the Blueprint then goes on to outline the many changes in lifestyle, social organisation and family planning that a transition to zero-growth might require. To stabilise population without violence or coercion, it proposes to accelerate the demographic transition to low birthrates and an ageing population which has since been observed in many developed economies. The Blueprint suggests that this should be brought about through a reform of New Zealand’s then-Victorian family planning laws, the provision of sex education in schools, free access to contraceptive advice and liberalised abortion practice.

Rightly aware of the outrage any one of these policy planks would have evoked in 1972, the manifesto matter-of-factly reminds its readers that ignoring such uncomfortable truths will only intensify future trade-offs between resource use and environmental protection, subsidising an unsustainable status quo with the resources of the future. It’s not easy or touchy-feely reasoning: every hard choice about quality of life and environmental impact should be made before it becomes even harder.

The Values Party believed that society would become more humane at the same time as becoming more sustainable - that the two traits would march hand in hand.

At the other end of the equation, the Blueprint also aims to reduce society’s resource use by changing the way businesses make decisions. Instead of inventing new goods that increase profit, the manifesto asks businesspeople to create products and services which help their local communities and place minimal strain on the environment. The Values Party presents this blending of corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship as a means of improving New Zealanders’ quality of life at the same time as subduing the unsustainable pursuit of growth and profit for their own sake. This diversion of energy and innovation towards positive ends defines the manifesto’s conception of how business might be part of the solution, rather than part of the problem.

To paint a picture of this counterfactual world of stable population and socially-minded business, the Blueprint lays out an alternative model for meeting human needs. It presents a world where people are prepared to accept a lifestyle that their planet can sustain, and to work for the dignity and freedom of their fellow citizens. This is both an expansive and aspirational vision of human nature, but the Party consistently argues that its programme of change will foster the empathy and solidarity that such a transition would require.

In their analysis, New Zealand’s endemic racism, sexism and homophobia are all founded in a culture that values conformity, productivity and consumption above all else, treating its people as ‘component[s] of mass production’. The Values Party believed that society would become more humane at the same time as becoming more sustainable - that the two traits would march hand in hand.

Although the manifesto argues that abandoning capitalist growth will make society more inclusive and accepting, it also recognises that all forms of discrimination require targeted remedial action. In constructing its platform for cultural change, the Blueprint draws on the many strands of social activism that were current in its time, outlining wide-ranging reforms that attempt to empower women, LGBTQ, Māori and Pasifika people in relation to their own, stated aspirations. By working to synthesise the varied analyses which underlay the struggles that were occurring in its society, the Values Party went far beyond the policies of their competitors at that point, but also inspired many politicians from other parties to expand their own sense of political possibility

the Values Party went far beyond the policies of their competitors at that point, but also inspired many politicians from other parties to expand their own sense of political possibility.

Despite being radical in their own time, many of the Blueprint’s ideas were slowly implemented by successive governments. Their gradual uptake can be seen in New Zealand’s foreign policy towards South Africa, where the Lange government finally severed diplomatic ties with the apartheid regime in 1984, twelve years after the Values Party asked New Zealand to make its ‘abhorrence of apartheid’ clear.

Incremental progress was also made in relation to the manifesto’s human rights goals; it would be another fourteen years before the Homosexual Law Reform Act finally decriminalised sex between men, and seven more before the Human Rights Act definitively outlawed discrimination on the basis of sexuality, gender identity, ethnicity, disability and other grounds. Law changes have shifted priorities in relation to the environment as well, with many governmental organisations, including the Department of Conservation and Ministry for the Environment, now explicitly required to balance human needs with environmental realities, and observe the Treaty of Waitangi in good faith.

Legislative progress and hard-won legal precedents are not the same as national transformation, though. It’s impressive that the Blueprint’s aspirations haven’t dated, but it’s deeply troubling that its prognosis for 1972 could easily apply to 2014.

To take one example, it is still easy to paint a very depressing picture of New Zealand’s environment and resource use. Since 1972, the area of land covered by native forest has continued to decrease, the impact of dairy farming has intensified and plans are still being made to expand extractive industry. Many indicators of pollution are also trending in the wrong direction, with private car use and the quantity of waste going to landfill both showing little sign of reduction.

Despite notable successes, such as the 1999 ban on native forest logging and piecemeal programmes in support of energy efficiency and waste reduction, New Zealanders’ total impact on the environment is both disproportionate and expanding. This is perhaps clearest in our per capita greenhouse gas emissions, which are already higher than most countries’ and projected to increase a further 13% by 2030. We have not yet struck a durable balance between our desires and the limits of our living planet.

We have not yet struck a durable balance between our desires and the limits of our living planet.

The Blueprint’s goals for liberation and social justice also remain unfulfilled, with this country’s deep-seated prejudices still manifesting in many ways. Economically, New Zealand is a highly unequal society, where the gap between rich and poor has widened faster than in any other wealthy economy over the last two decades. It is a place where many people live in substandard homes, struggle to access medical services, and are unable to feed their children. Racism, sexism and homophobia also remain visible on our streets and in our political debates. Women’s wages are an average of 10% below that of men, the rate of unemployment for Māori is approximately twice that of the population at large and multicultural immigration continues to be a focus for aggression and grievance. These are not the markers of a society which has prioritised equity and justice; they are reminders that our social and economic paradigm remains unstable and dangerous, forty-two years after the Blueprint for New Zealand saw a need for radical change.

Over those four decades, many people have taken up the Blueprint’s proposals and used them to alter the course of this society. It is a text which has lived a long and varied political life. In the present, though, the Blueprint must be read as a provocation, rather than a prescription. It embodies a view of the world which recognised fundamental problems in economics and social organisation but which knew nothing of the cultural and technological shifts which have has defined our age. Because we take for granted so many realities that would have been in the realm of speculation to the manifesto’s authors, it is now a document definitively of the past, even though it imagines a world which is, in some ways, beyond our own.

it is now a document definitively of the past, even though it imagines a world which is, in some ways, beyond our own

What does ultimately date the Blueprint is not its ideals, or the problems that it identifies, so much as its conception of the role of government. In 1972, Keynesian economics, fiercely parochial nationalism and bipartisan acceptance of a strong welfare state made powerful, activist government a central force in New Zealanders’ lives. Young people were still expected to perform national service, government subsidies made up a substantial proportion of farmers’ livelihoods and the first privately owned radio station, Radio Hauraki, had only intruded on total government control of broadcasting six years previously. Whatever New Zealanders thought of their government in 1972, few would have questioned that it was an institution of overwhelming power and authority, with the leverage to force deep change for good or for ill.

Even today, New Zealand’s political system continues to centralise great control in the hands of our leaders. Its single-chamber parliament is unchecked by either a directly elected executive head of state or a court with the power to strike down legislation. In the time of the Blueprint, this governmental agency was even more pronounced. The old, first past the post electoral system created high barriers to entry for third parties and produced majority governments with such frequency that it has been characterised as an era of ‘elective dictatorship’.

This was a paradigm which meant that shifts in political calculus could cause sudden and striking upheavals in New Zealanders’ lives. During the 1951 Waterfront Lockout, for instance, Sidney Holland’s National government was able to rapidly construct what amounted to a police state, where citizens were banned from expressing support for striking workers, or providing aid to their families, and soldiers were deployed to replace locked-out unionists. Living in an era when elected leaders openly exercised such powers of intrusive coercion on a large scale would certainly make the radical policies of the Blueprint seem much more plausible than they might today, where centralised force is deployed with greater selectivity, secrecy and prejudice.

Elsewhere, too, deep and constant change has defined our political environment for three decades. Wide-ranging neoliberal reforms have transformed New Zealand from a nation of protected industry, generous benefits and free education into one of the least regulated societies in the developed world, shattering public perceptions of government’s capabilities and responsibilities.

Since 1984, generations of politicians - from Roger Douglas and Ruth Richardson to Jamie Whyte and John Key - have ruthlessly questioned the state’s obligation to pursue social transformation and its competence in providing public services. The postwar notion of government as a benevolent, wise and kind protector has been supplanted by an equally uncritical championing of free markets as the primary instrument for determining and advancing the social good.

The postwar notion of government as a benevolent, wise and kind protector has been supplanted by an equally uncritical championing of free markets as the primary instrument for determining and advancing the social good.

This tendency has dominated governments from both major parties since 1984. It has led to an extraordinary degradation of public services, encompassing the closure of rural hospitals, post offices and schools, the end of free tertiary education, the expansion of charges for publicly-funded healthcare, a reduction in the unemployment benefit to 80% of the level necessary for adequate nutrition, the sale of publicly owned assets and the contracting of private companies to run prisons for profit.

This retreat of government from society’s central needs has fed a growing cynicism among many New Zealanders, who have found it hard to reconcile with politicians’ continuing claims to care about the lives of ordinary people. In an era where government no longer considers itself obliged to provide a meaningful social safety net, it is much harder to imagine a government leading the transition to an equitable, static and universal standard of living.

It is also more difficult to imagine the electorate trusting politicians to lead such change. Trust in parliament has slumped in the decades since the Blueprint was conceived; twenty years later, politicians’ trustworthiness was polling close to that of used-car salesmen. It has been suggested that successive governments’ embrace of deregulation, asset sales and service cuts, despite long-term public opposition, has been one major driver of this trend, as well as an increasingly critical understanding of authority figures in general. This distrust and disengagement are frequently cited as causes for declining electoral participation, meaning that elected officials are now considered by some to be part of the problem, rather than a group who might lead change for the better, whatever their stated goals or party affiliations.

In one sense, the Blueprint reminds us that things that don’t have to be this way; that futility and indifference are not inevitable responses to political difficulty. The Blueprint’s idealism and its belief in the transformative possibilities of an engaged government and citizenry may seem out of step with the attitudes of some New Zealanders, but they also remind us that those attitudes are the conditions, not the limits, of political change in our time.

Indeed, a substantial section of this society remains deeply engaged in politics as they currently exist, trying to address our society’s rolling crises with a range of interventions (economic, social and environmental) that are in some ways as hopeful as those the Blueprint proposed. The question now is not whether their attempts to recalibrate society’s goals are necessary, but whether such change will occur in time to avert the catastrophic scenarios originally predicted in The Limits to Growth, and more recently affirmed by reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Such systemic transformations are infrequent and difficult, but they become more feasible when people understand the historical roots of their present conditions, as well as how their local realities tie into wider global patterns. This interconnectedness and contingency mean a single, broad-brush solution is rarely able to address all aspects of a particular problem, but it also means that the emergent stresses of our society can be addressed in many ways at once, at a number of scales and from different directions.

For a similar document to be as progressive today as the Blueprint was in its time, it would not only have to recognise the present threats to a liveable future, and describe a wishlist of government actions to control them, but also analyse how individuals and groups can foster the changes our world needs, even where government may be reluctant to act on their behalf. Changes in our society’s expectations of government, and our government’s sense of its own responsibilities, mean that the top-down change proposed by the Blueprint can only be one aspect of a multifaceted response to global and national struggles. Equally important is an understanding of how government can be redirected towards this progressive leadership role while political awareness and change is worked into the fabric of everyday life. Approaching the problems of our time on any one of these scales doesn’t preclude approaching them from any other: all approaches to progressive change are incomplete in isolation but many of them are also feasible, effective and complementary.

the top-down change proposed by the Blueprint can only be one aspect of a multifaceted response to global and national struggles

Our society has certainly not achieved the Values Party’s goals of peace, economic justice and sustainability. In fact, it often seems as if these ideals are very far from our leaders’ thoughts. We have chosen a path that is radically different from the one proposed by the Blueprint. It’s a path which has created a world that is as foreign to the Values Party’s aspirations as those aspirations are from the world of 1972.

Because it contains ideas which run so counter to our usual political expectations, the Blueprint for New Zealand is a genuinely challenging document; a text which steps far enough from the conventions of its time to remain provocative and open forty-two years after it first disrupted political debate. It is a glimpse into what an earlier generation dreamed might be possible and it demonstrates how even the most radical imagination can foster real social change.