Don't Get Comfortable: A review of The New Animals

Briar Lawry reads Pip Adam's The New Animals, and discovers a compelling novel about the fashion industry that she thinks has a simple narrative, but...

There are few New Zealand writers as exciting and original as Pip Adam. Briar Lawry reads Adam's The New Animals, and discovers a compelling novel about the fashion industry that she thinks has a simple narrative, but...

I have a particular soft spot in my heart for Pip Adam. As a bright-eyed new arrival to the capital, the first book I bought with my Unity shop-girl discount was Adam’s I’m Working On A Building; it’s a book I kept coming back to – at least in part due to twitchy bookseller inclinations to double check the way its intentional upsidedownness was positioned on the shelf. That book was the perfect way to cement myself in the literary wonderland that is central Wellington – challenging, compelling, complex. Completely different from anything I’d happened upon before.

With that in mind, The New Animals seemed curiously simple at the outset. Characters with clear-cut pressures on them, and a sharp rendering of contemporary Auckland. Reading the novel gave me that specific sparkling thrill of places I know.

The fact that the very first paragraph of the book features one character’s internal monologue whine about St Kevin’s Arcade’s descent into shiny gentrified cultural decrepitude is an immediate hook. Particularly, a hook for anyone with overwhelming memories of lackdaisical younger days slouching around in cardigans telling one another how cool we were. Immediate connection with the protagonist. So far, so simple?

The New Animals is about the fashion industry, so says the blurb. For the first two thirds of the book that much is clear. The blurb also refers to the divergent positionings of the Generation Xers and millenials of fashion: cynicsm vs. sincerity. But some things transcend generational divides, and the book’s varied viewpoints are connected by a sense of feeling hard done by. The grim realities of the characters will probably feel uncomfortably familiar for anyone working in any creative industry – be it fashion or theatre or books. The starry eyed up-and-comer. The jaded stalwart. The improbably successful youngster who happens to have significant familial financial backing.

The New Animals is about the fashion industry, so says the blurb. For the first two thirds of the book that much is clear.

The multiple characters mean more deviation from simple narrative – but each character’s relationship to the others is fairly explicit. They are working towards a single collective goal: shooting a new fashion collection the next morning.

Every character has their cross to bear whether it’s the burden of success or a canine reign of terror on a St Johns studio apartment or frenzied overnight garment recreation or a specific kind of a yearning for the ocean.

But there’s no resolution to those issues faced – not that you, the reader, will immediately be aware of that. But at a point, when things have taken a turn for the odd, then odder still... there’s a moment of realisation that you’ve gone entirely off course with a character you had no cause to give particular thought to. Which is surely, in part, why the character in question has felt compelled to take their particular journey.

It’s difficult to go into a great deal of detail without spoiling the unexpected trajectory of the book. But as mentioned at the start of this piece, Pip Adam has a history of carving out new and different kinds of storytelling. So to discover that things veer in an entirely unexpected direction should, in some ways, not come as a surprise. Let this paragraph serve as a warning – detail lies ahead.

Elodie. Elodie seemed like such an unassuming character. Mentioned in a smilingly cherubic kind of way by different characters. Her first mention comes from Carla: ‘Elodie would be good for this. They probably needed Elodie.’ The first time we meet her, she is on the phone to Carla: ‘Everything in her was so light it floated up and away.’

Not name-checked on the blurb – a calculated decision. Elodie falls in the gaps. She is a millenial – yet the other millenials given voice in the book are the leaders of the label, the fashion forefront wunderkinds. Elodie is a make-up artist, relegating her role to supporting, alongside the Generation X hair stylists and pattern cutters.

And yet, it is in the end Elodie’s story. When Elodie is given her own voice, that is the last we hear from anyone else. Whether Tommy, Carla, Sharona et al ever manage to make their last minute shoot of ill-prepared clothes work is unknown. As Elodie leaves the workroom, we leave the wider story... even if we don’t know it at the time. Her sparkling optimism – even when alone with Doug-the-pitbull and her thoughts – is a brittle cover to a sense of existential dread that drives her journey seaward.

At some point, though it’s hard to pin point when, exactly, the story drifts into the gently fantastical.

At some point, though it’s hard to pin point when, exactly, the story drifts into the gently fantastical. Is it at her first suggestion of a giant woman on the seabed, or before? After? When she reaches a the cold water of a channel, do we imagine that instead of her ensuing tussles with a persistent octopus and discovery of a boat with a skeleton crew, she is dreaming as hypothermia sets in?

These are all thoughts after the fact, however. As I read, I was perfectly willing to entertain Elodie’s thoughts as she swam further and further out to sea. The improbabilities, the impossibilities washed over me as if the book had always had a vein of magical realism through it.

For the first hundred or so pages, my interpretation was that it was those crazy darn millenials who were the 'new animals'... but that still didn’t seem quite right. Floating out in the open ocean, the book’s title became a little clearer: ‘Clothes weren’t right for her, they didn’t belong to the animal she thought she was.’ Worth noting too, is Elodie’s reference to ‘other swimmers, temporary swimmers,’ as a point of difference to her as a newly water-bound creature.

In this new realm, it’s only Elodie’s specific mentions of Carla (and her infatuation with her) that maintain the thead of connection to the first part of the novel. For a while, there was Doug. Until there wasn’t. Then, it is just Elodie, the ocean, and occasional cephalopod appearances.‘She imagined everyone she knew would ride it out. To the bitter end, but not her. She had youth on her side. She laughed out loud for all of them. She would get it ready for them, for when they were finally ready for the new world.’

This is not a book for those who need their stories to have a traditional beginning, middle and end. Everything in this book remains open-ended and unresolved. But it is compelling. It is beautifully executed, thought-provoking in a head-scratching kind of a way. By the time you realise you’ve veered off course, you’re in far too deep and must continue. And you should.

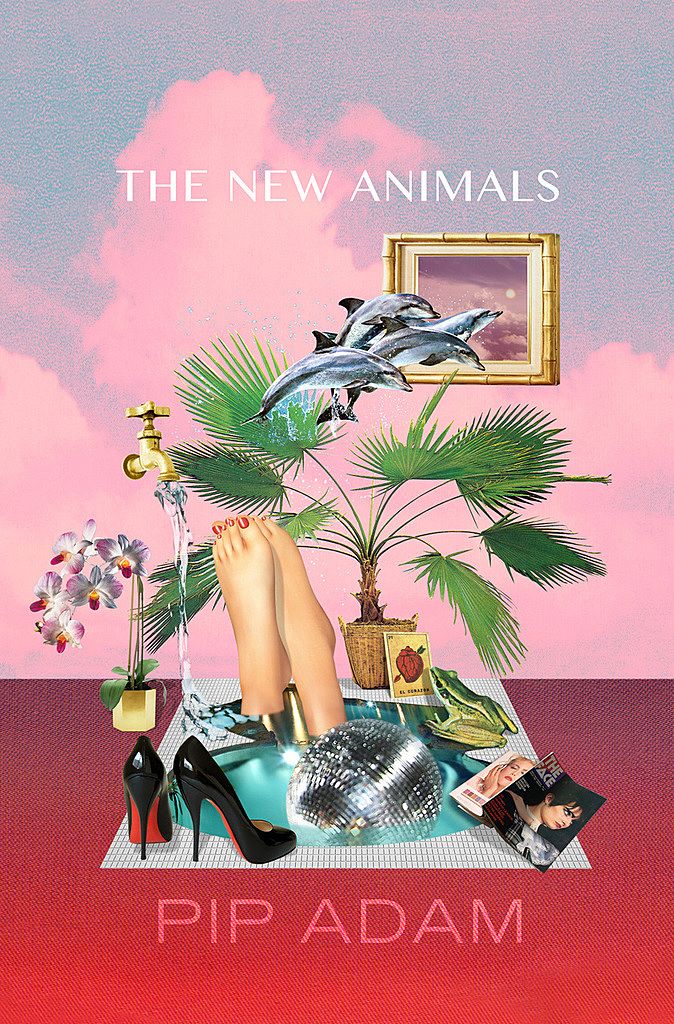

Feature image of Pip Adam by Victoria Birkinshaw. The New Animals is available from Victoria University Press.