Naughty Nanas and Sad Old Men: How We've Screwed Up Old Age on Our Stage

From millennial writers to the most successful playwright in New Zealand, Adam Goodall digs into the mistakes that Aotearoa playwrights keep making when they write stories about old age for the stage.

Roger Hall is the most successful playwright in New Zealand, but it looks like he's scared of everyone below retirement age. What's worse is that it might just be our fault... and not in the ways you think. Adam Goodall digs into the mistakes that Aotearoa playwrights – especially the young ones – keep making when they write stories about old age for the stage, and what needs to change to get them right.

Given his reputation for writing breezy comedies for Auckland Theatre Company subscribers, Roger Hall’s 2007 play Who Wants To Be 100? (Anyone Who’s 99) is pretty fucking bleak. Set in a residential care facility on the outskirts of Tāmaki Makaurau, Who Wants To Be 100? is about four men whose ageing bodies and minds are working overtime to bring them down. There are a lot of jokes about Alzheimer's, strokes and shitting yourself. There are also storylines about dying friends, cheating wives and getting abused by the night nurse. It’s a lot.

Hall outdoes himself with one particularly brutal subplot. Leo Maddox, a former All Black, gets a letter from his daughter, Mary: she’s coming over from Brisbane to visit. His kids don’t visit often so he’s understandably thrilled. On the day, though, things go south. Fast.

Leo loses control of his bladder before Mary arrives, ruining his pants. When she finally gets there he’s trapped in his anger, grouching about his age and how she’s only just visiting now. Two of his friends add to the stress by interrupting and interfering while he and Mary are talking. And then Mary reveals why she’s really there: her business has gone under and she and her husband owe their creditors $40,000. Won’t Dad just sell his empty house and give her the money?

Leo refuses. Mary rips into him, calling him out on how he was never there for her and her sisters when they were kids. “You’d have turned up quick enough to watch us play if we’d been sons.” She leaves, and the scene ends on the following stage direction –

HE SITS THERE, LONELY, DESPERATELY SAD.

THEY ALL SIT IN SILENCE FOR A MOMENT FEELING SORRY FOR LEO.

Another version of this betrayal turns up in Hall’s knockabout 2015 comedy Last Legs. Slimy National voters Garry and Trish describe how once they’d decided to move into their North Shore retirement village their children descended on their home like vultures, taking all of their furniture and then selling it on Trade Me months later. “This is what got me,” Garry says bitterly, “my son said coming here – because of the Capital Depreciation clause – robbed them of a chunk of their inheritance.”

You’d almost think Hall was scared of getting old. But there’s more to it than that. In 2012’s You Can Always Hand Them Back, Grandma and Grandpa are outraged that “People don’t do ‘thank yous’ these days!!” In 2014’s Book Ends, wealthy publisher Paul gets ripped a new one for telling the girl on the till that, “A smile or a ‘Good Morning’ would be nice.” A New Zealand Herald review of 2004’s Spreading Out praises the way “[t]wo generations of disappointing children are sketched more quickly, and with less charity, by Hall's pen, to what is, ultimately, perfect effect.”

It might be that Hall is just writing crowd-pleasing stereotypes, same as he does elsewhere in his work: National voters are selfish boors, Greenies are sanctimonious scolds, etcetera, etcetera. It might be that Hall is capturing a zeitgeist, reflecting his generation’s general attitude toward millennials and Gen X-ers. It might even be that Hall, personally, just wants the kids to stay off his lawn. But these stereotypes – sometimes played for laughs, sometimes used to highlight the gross inequities of getting old in the new millennium – reflect a contempt for those of us younger than retirement age.

“This is what got me,” Garry says bitterly, “my son said coming here – because of the Capital Depreciation clause – robbed them of a chunk of their inheritance.”

It’s not an unfamiliar contempt. We’re pretty used to hearing that we’re destroying the society built by our elders. According to them, we’re killing everything from committed relationships to strong handshakes. Hall’s elderly characters reflect the timeless, endless cultural phenomenon of not trusting your kids to take over the steering wheel. His characters don’t like our fads, don’t share our beliefs and don’t trust our motives.

It’s easy to make fun of – look at this out-of-touch old man, shaking his fist at the clouds – especially because we don’t make the same mistakes. We don’t hold old people in contempt, we don’t peddle condescending stereotypes about them, we trust them and we recognise their humanity and we reflect that in our movies and our books and our theatre. Right?

In a 2015 New Yorker article titled “What Old Age Is Really Like,” writer Ceridwen Dovey relates the results of a 2009 survey of American attitudes towards old age. That survey found that there was a “sizable gap between the expectations that young and middle-aged adults have about old age and the actual experiences reported by older Americans themselves.” Dovey explains how young and middle-aged adults “anticipate the ‘negative benchmarks’ associated with aging (such as memory loss, illness, or an end to sexual activity) at much higher levels than the old report experiencing them.”

This is the case in New Zealand, too. In a 2016 report by the Office for Seniors Te Tari Kaumātua titled Attitudes towards Ageing, 56 percent of respondents aged 18 to 34 (those awful millennials) and 45 percent of respondents aged 50 to 74 (those horrible boomers) said that they worried about what life would be like when they reached old age. A majority of millennial and boomer respondents said that they were particularly concerned about the possibility of physical deterioration, mental illness and dementia. For many, ageing was synonymous with sickness and degradation.

Those attitudes are reflected in the stories we tell about ageing, especially on our stages. Some of these narratives are narratives of decline, stories about the cruelty and tragedy of getting old. Take, for example, Gary Henderson’s 2004 drama Home Land.

Staged at the Fortune, Circa and Court Theatres between 2004 and 2010, Home Land tells the story of Ken, a stoic 80-year-old farmer who gets around on a walking frame and downs a cocktail of pills each day. He was once a mountain of a man, not unlike Mr Thorpe, the tragic hero of Owen Marshall’s understated short story Requiem in a Townhouse, but now he regularly falls, drops things and loses control of his bladder, reprimanding himself and muttering “clumsy old man” every time. Home Land even opens by making a spectacle of Ken’s failing body –

KEN TAYLOR enters the lounge from the interior of the house. He is 80 years old and uses a walking frame with a cane hanging from it. He has an emergency call button hanging around his neck. You can see he used to be fit. He is crossing the room, heading for his chair. He walks with difficulty. His legs just don’t seem to do what he wants. The walking frame starts to get away from him and he leans further and further forward as his feet lag behind. Finally he is stuck. It would almost be comical if not for Ken’s obvious distress. He tries vainly to walk his legs up to the frame. Finally he takes one hand off the frame to reach for the cane, but his other arm can’t hold his weight. A look of panic seizes him as he loses control and crashes awkwardly and painfully to the floor, overturning the frame. he lies there a moment.

KEN: Aahh ya stupid, useless old man.

Mustering all his strength, he rolls, crawls and claws his way up into the chair. It’s a huge effort and he ends up sitting awkwardly.

Ken can’t look after himself and his children can’t do much better, so they prepare to move him on from the land he once farmed to a retirement home in Dunedin. He fumes about the injustice of it all, mostly in silence, sometimes out loud. “May as well just jump in the offal pit,” he spits. He resents and resists the tyranny of his age right to the end, briefly reclaiming his dignity when he walks through his home for the last time, unassisted. This isn’t subtext, mind. This is straight text. Henderson writes in the stage directions –

This is Ken’s final dignified moment. The staging should acknowledge and respect that without letting it become corny or overblown.

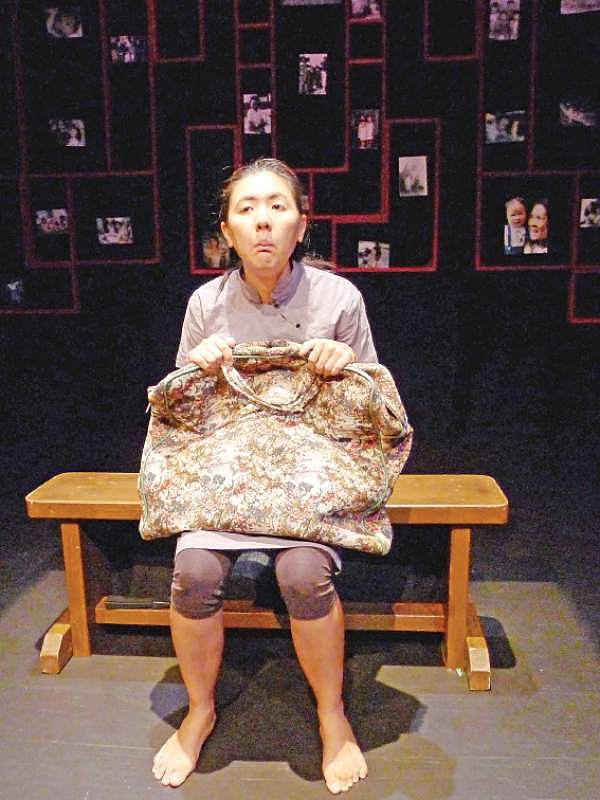

Other plays see ageing as an injustice to be challenged and corrected. Instead of sick, chaste, miserable old people, we get naughty nanas and eccentric granddads. Take Por Por Grace, an 87-year-old who stages a daring escape from her Hong Kong nursing home in order to attend her granddaughter’s wedding in Aotearoa, in Renee Liang’s 2015 comedy-drama Under the Same Moon.

Por Por reflects on her life with romance, and that romantic perspective has an affecting, bittersweet edge – she enjoys talking with her “old friend” the moon and sometimes gets lost in her heartsick memories of her husband Wing. But Liang also plays up Por Por’s eccentricities, building to an extended sequence in which she takes a spontaneous tour around Aotearoa, skinny dips at Lake Taupō, gets arrested and is driven by a police officer back to Tāmaki Makaurau just in time for the wedding.

Sexually active seniors are played for shock and laughs in Bruce Mason Playwriting Award winner Jess Sayer’s 2015 play SHAM, a dark comedy about a battle of humiliation between 50-something Meryl and her dying older sister Neva. It’s not even five minutes after Neva walks in the door with Ann, her eccentric partner of 34 years, that Ann bellows –

ANN: We’re a couple of big old unashamed dykes, aren’t we dear?

NEVA: You’ll have to excuse Ann. She likes to shock people.

ANN: Doesn’t have the same punch as it used to though. Everybody’s decided to get all, “Gay rights, gay rights, they’re people too!” It was far more fun when everyone hated us.

FERN: Was it?...

ANN: Yes! It’s awful now – all the fun’s gone out of it! Getting hard to shock people these days. I decided perhaps if I dyed my hair orange I might keep some of my shock value. But it’s more red than orange, isn’t it?

Ann emerges as a stable, endearing counterpoint to Meryl and Neva, but that doesn’t stop Sayer from exploiting Ann’s open sexuality and mild eccentricities for comedy. She candidly explains that she and Neva “still have quite the sex drive” and that she could never be a vegetarian: “Still enjoy that sort of meat, if you catch my drift.” When Fern, Meryl’s 20-something-year-old daughter, tells Ann that she has a boyfriend, she quips, “You’d have better sex with a woman.”

SHAM might seem like an unconventional example of a naughty-nana narrative because Neva and Ann are only in their late 60s. However, Attitudes towards Ageing reports that New Zealand millennials typically think of old age as starting at 60. Sayer, who was shortlisted for Playmarket’s Playwrights b4 25 award in 2015 for SHAM, reflects that thinking in these characters. Neva and Ann might not be in their 80s, but Sayer writes as if they were. In particular, Sayer treats Ann’s active interest in sex as transgressive in and of itself. It's a conscious play for laughs based on the 'negative benchmark' that ageing means losing your appetite for sex but all it does is reinforce that benchmark's existence.

Ann candidly explains that she and Neva “still have quite the sex drive” and that she could never be a vegetarian: “Still enjoy that sort of meat, if you catch my drift.”

Dovey calls these narratives the “two dominant cultural constructions of old age”: “the doddering, depressed pensioner and the ageless-in-spirit, quirky oddball.” These narratives are are just as dominant in our depictions of old age as they are in America. The older characters that we put on our stages – and this is really key, because we barely even bother to write them in the first place – are typically variations on these narratives. Take the comically frustrated elderly bank robbers, one balancing a shotgun on top of his walking frame, in Joe Musaphia’s 2003 comedy Ugly Customers. Take the eccentric wiccan grandmother in Angie Farrow’s 2017 young-adult play August Moon. Take the matter-of-fact brothel owner hellbent on humiliating her viewers with sexualised audience interaction in Katie Boyle’s 2018 comedy Pat Goldsack’s Swingers Club and Brothel.

Even Roger Hall isn’t immune. In Who Wants To Be 100?, which he wrote in his late 60s, Hall makes a series of jokes about the Alzheimer’s-suffering Alan having sex with Daphne McGovern upstairs, much to Mr McGovern’s chagrin. In Last Legs, written a decade later, Hall writes a character named Kitty, a sexually active resident at a retirement village. Kitty’s hounded by horny old men and Hall plays their horniness for laughs, but he plays her promiscuity and unashamed sexuality for laughs just as often. In the play’s chaotic final scene, another character almost dies of a stroke while doing some doctor-nurse roleplay with Kitty.

Even though Hall was well into old age at the time he wrote Last Legs, he was still falling into the same traps that ensnare younger writers. Everyone (with luck) gets old – that’s part of what makes it such a complicated node for discrimination and prejudice. Maybe one of the reasons for that is that there’s such a difference between getting old and thinking of yourself as getting old. How does the adage go? That old people still feel like they’re 25 inside?

“In a way, old people are invisible, and we’re not very attractive or interesting to younger people.” The mononymous writer of groundbreaking feminist dramas like Wednesday to Come and Setting the Table, Renée (Ngāti Kahungunu/Scots) has deliberately been developing and writing work in recent years that centres older women. This, she says, is in part because the experiences of ‘being old’ depicted in Aotearoa theatre and literature are full of the same stereotypes. “We’re lonely, we don’t see enough people, we don’t eat well, all those kinds of things.”

“I’ve no doubt in lots of cases that’s absolutely true,” she says, “but there doesn’t seem to be any allowance for those of us who aren’t like that.” She expresses that same frustration in her 2017 patchwork memoir These Two Hands: “When I hear politicians and others refer to me as ‘the elderly’ like we’re all the same height, the same size and genderless – the other – then I feel like having a tantrum. Saying ‘I’m old’ has vigour. There’s a faint little tinge of ‘so what?’ about it.”

"In a way, old people are invisible, and we’re not very attractive or interesting to younger people.”

Many Aotearoa writers work from the baseline that old age is about loss: missed opportunities, dying friends, bodies that just don’t work like they used to. There’s also this assumption that old people universally “don’t feel anymore,” says Renée, that they don’t feel “anger or jealousy or heartache or any of those sorts of things,” because they’re old. That old people are just waiting for the Reaper.

But that’s just not the case. People experience old age differently. Some get worn down quickly, others slowly. Many more stay active and intellectually hungry. Even if they’re slowing down, they continue to work and they continue to put work out into the world. “I have a whole life going on inside me,” says Renée, “that to everyone else who sees me, they just don’t know about it! They see this old woman, and she’s got grey hair, and she talks and she swears, and she works.

“I mean, being old means you still go on getting annoyed and irritated.”

We don’t see all of this on our stages. Characters like Oscar, the 70-year-old furniture mover in James Cain’s 2018 comedy-drama Movers, are rare at best. Most of the time, the old characters we put up on the boards are just sketches without any shade or colour: old and batty, old and wise, old and sad. They’re not shown as full people. They’re just conjunctions. It’s enough to drive anyone in their 70s or 80s to revolt.

Renée says that this homogeneity is the result of younger writers only working from what they see in front of them. Without experiencing old age or talking to the people in their lives who are experiencing old age, what they ‘see’ ends up being influenced by their own assumptions – and we know what those assumptions are.

It’s a short jump from there to writing and devising sentimental depictions of old age. Sentimentality can take on many forms. A tear-jerker portrait of elder loneliness can be just as sentimental as a rose-coloured story about a preternaturally wise grandma or a zany granddad who’s always on adventures. All of these stories are ginned-up to make old age ‘more interesting’ for a younger audience and they all end up reproducing stereotypes in lazy and unthinking ways. They say this is how an old person is, or they say this is how an old person isn’t.

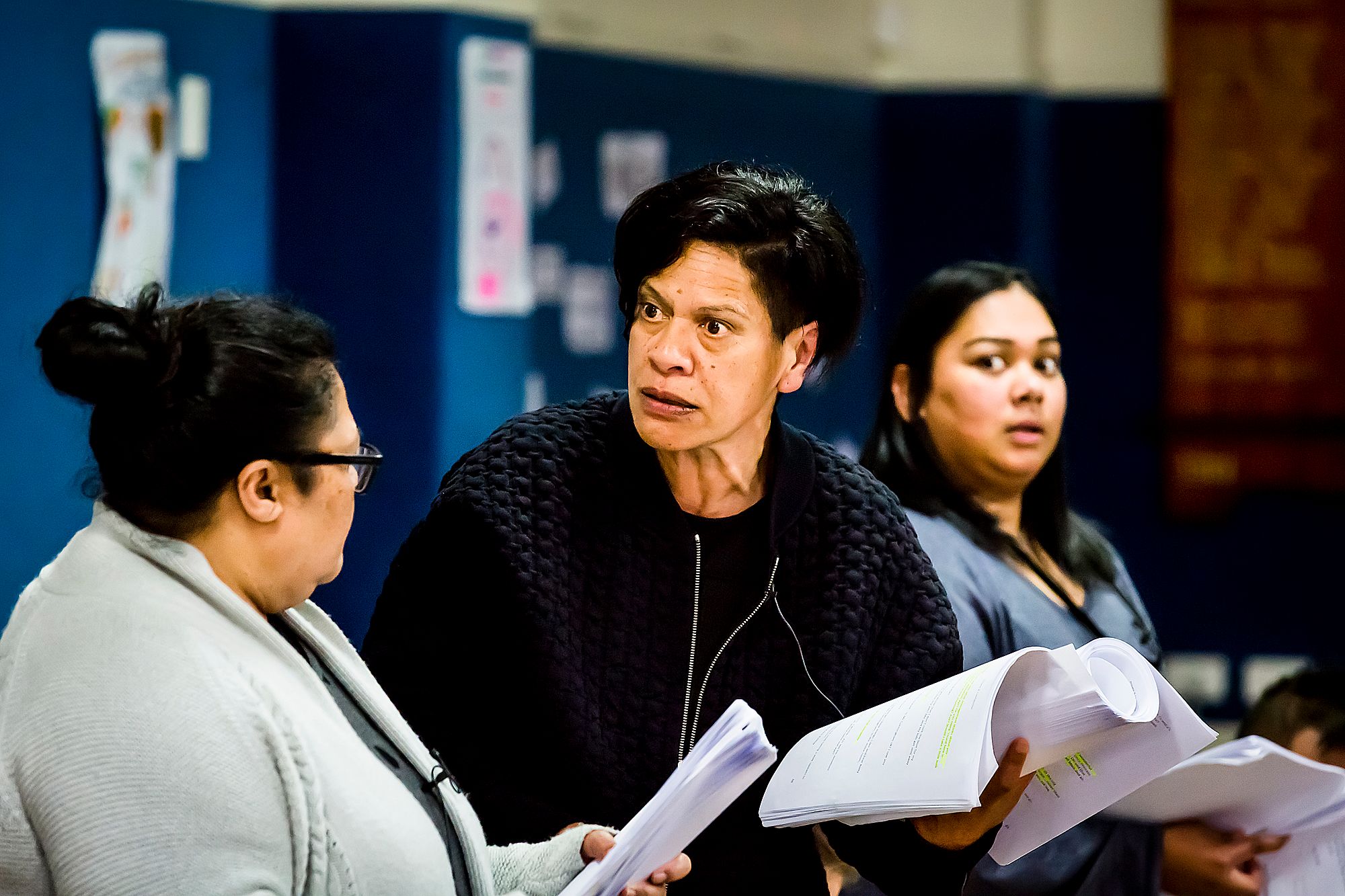

Winner of the Outstanding New New Zealand Play of the Year Award at the 2018 Wellington Theatre Awards, 48-year-old D F Mamea’s 2017 play Still Life with Chickens pushes past these regressive narratives and presents a portrait of old age uninfected by sentimentality. Still Life with Chickens roots itself in Mama, an 80-something Sāmoan woman who is “bowed by the years but with the gardening stamina of someone a quarter her age”. When the play opens, Mama has just buried Blackie, her cat and companion of many years.

Blackie’s death has left her essentially alone in her house, waiting hand and foot on her ill and heavily dependent husband. When a chicken (played in the Auckland Theatre Company production by an expressive and absolutely bloody delightful puppet) intrudes on her prized garden, Mama forges an unlikely and extremely wholesome bond with the bird, who she names Moa.

Mama is a contradictory woman, full of love and irritation and grievances and regrets. She is frustrated at how little her family visit – “E shush, visiting every weekend doesn’t count, a...” – but peppers her lesbian granddaughter, the only one who regularly calls, with questions about when she’ll ‘come right’ and find a man. She misses her friends from “the old days,” the last of whom dies during the play, but her simmering prejudices keep her from connecting with the community on her street, the Māori, Indian and Palagi families living next door.

“What I didn’t want to write was a piece about how hard it is to be old, how hard it is to be lonely and old.”

Mama doesn’t undergo a great transformation, either. In her New Yorker article Dovey writes that “[g]rasping for closure might be the goal of fiction, but it is not necessarily the lived experience of old age.” Mama’s spent most of her life distracting herself from decades’ worth of regrets. Moa’s arrival gives Mama someone to talk to about those past hurts, and Moa’s disappearance forces her to reckon with them. But at the end of that reckoning, Mama resolves to return to the old rhythms of her life –

God, if Moa comes back safe and sound, I… E, who am I joking, a? If you bring her back to me, then good. And if you don’t, ia, I understand, because… because life is for the living, a. And until I die, that is what I will keep doing.

Unlike plays like Home Land and Who Wants To Be 100? which valourise those who ‘suffer’ through the losses and hardships of old age, Still Life with Chickens depicts old age as just another chapter, albeit one informed by the memories and regrets that accumulate over the years. Mama isn’t mourning the loss of her youth or acting out as though she never got old in the first place. She’s just plugging away at her garden and at life in general, stewing over mistakes she made decades ago and nursing wounds that never really healed.

“What I didn’t want to write was a piece about how hard it is to be old, how hard it is to be lonely and old,” Mamea says. “Mama is just whoever she is at that time. She’s lived her life, and it could have been better, she could have made better choices, she could have been a whole lot more, but she is what she is.”

Sentimentality isn’t just a problem for the page. It’s a particularly volatile problem in theatre, because old characters are written to be performed live. They exist as living bodies, sharing space with the audience. How they move, how they talk, how they respond to others in the space – all of these things are physical, present and immediate for the audience watching. “When we write a part for an older person,” says Renée, “the audience actually sees that.”

That presence can be positive and make audience members feel seen and represented. Renée recalls a woman approaching her after a performance of her play Wednesday to Come in August 1984 at Downstage Theatre. The woman wanted to thank her for writing the character of Granna, a woman in her late 70s who spends much of the play recording in her diary things that other characters say. “[She] thanked me for what I was saying about people with dementia,” Renée says, “[and] I’d never seen Granna in that light, but the woman in the audience had immediately seen that – because she’d had experience, I suppose.” Granna was played by Davina Whitehouse, who was in her 70s herself.

A sentimental portrait of old age, though, can poison a performance. Asked to play a collection of stereotypes, actors, especially younger ones, can easily fall back on more stereotypes around how old people move and talk. They might hunch over and make themselves small, shuffle their feet, talk slowly, shake when they’re carrying things, move with stiffness or obvious pain. All of these movements play into the image of old age as sad and sick and painful to experience.

On the other hand, if they’re playing old people who are ‘young in spirit’, they might shake things up a bit. They might move a bit faster or with a bit more elasticity. But they’ll still use those building blocks, mashing the two together. They create an old person who moves differently to other old people in order to draw attention to how much they’re not like other old people.

In his one-man play Talofa Papa, 26-year-old Kasiano Mita plays an old man whose age is communicated through these classic movements. Papa is hunched over a cane for most of the play, knees bowed, shuffling slowly from place to place. Even this play, which is largely sensitive and thoughtful, and critical of Western cultural perspectives about ageing and how we respond to old age, can’t help being sentimental about older family members.

Like Still Life with Chickens, Talofa Papa deals with elder loneliness, a hot topic in public-health circles. Papa lives in an apartment in a retirement home; the show opens with his family arriving for Grandma’s birthday. We, the audience, play his family.

Papa’s age isn’t just communicated through his movement, then; it’s also communicated through that familial relationship. Papa teases us like he’s known us since childhood and scolds us for arriving late or laughing too loud. He picks out individual audience members from the crowd, calls them his “favourite” and gushes about their successes to the rest of us. He asks his favourites to prepare a dance or to lead us in a song for Grandma’s birthday celebrations.

The celebrations start – and yeah, here’s where the spoilers start too – when a chosen grandchild brings out Grandma’s urn. Grandma, we discover, died several years ago. Rather than attending a surprise birthday party, we’re here with Papa to celebrate her life.

“In Pacific culture… the older generation, they live at home with us, so homes don’t necessarily exist in our culture."

Talofa Papa doesn’t wallow in how sad this is, nor does it try to force on us a cheery tale of a man without age who’s bounced back from grief. Instead, it’s a sensitive story about the value of coming together and remembering together, especially as our families get older. It’s a shared experience, understated and warm and communal.

In that context, Mita’s choice to set Talofa Papa in a retirement home is a pointed critique. “In Pacific culture… the older generation, they live at home with us,” says Mita, “so homes don’t necessarily exist in our culture. It’s not necessarily frowned upon, but the way we were brought up is that our parents looked after us when we were growing up and then, once we’re older, it flips, it’s our time to take care of them.

“I wanted to explore a route where life just gets so busy within our community that we’d try that route [of elderly care]. I wanted to explore what that looks like.”

Māori, Pacific Island and Pākehā communities all have different cultural perspectives on how we should accommodate and care for the elderly. The 2004 study “Intercultural Residential Care in New Zealand,” by University of Auckland academics Dr Liz Kiata-Holland and Prof Ngaire M Kerse, is particularly helpful for understanding this difference. In their study, Kiata and Kerse interviewed a number of caregivers and residents at a residential care facility in Tāmaki Makaurau. All of the interviewed caregivers were of Pacific Island heritage and most of the interviewed residents were Pākehā – samples representative of that care facility’s broader population.

Coming from Sāmoan, Tongan, Fijian and other Pacific backgrounds, the caregivers shared Mita’s understanding of how elderly care is done in their communities: the parents care for their children, then the children care for them in their old age. “A prime example,” Kiata and Kerse explain, “can be seen in Sāmoan etiquette”:

... the relationship between the carer (usually a young person) and the elderly is marked by fa’aaloalo (respect) and alofa (love), and is mutually understood as such. Basic necessities such as food and physical care are given to the elderly at the carer’s discretion. However, the older person and the caregiver understand that submitting to the role of “cared for” does not necessarily mean loss of empowerment for the aged. This is because, culturally, the respect accorded to the elderly is paramount.

Similarly, elderly Māori may have the status of kaumātua conferred upon them when they reach a certain age, carrying mana such that they are then entrusted with carrying the culture of their iwi. Kaumātua are expected to fill a number of roles that are “critical for the survival of tribal mana,” Sir Mason Durie writes in his 1999 paper, “KAUMĀTUATANGA / Reciprocity: Māori Elderly and Whānau.” These roles include nurturing mokopuna, speaking on behalf of the iwi and carrying their culture. These roles can be demanding, especially for older kaumātua, but “the reciprocal obligations on the tribe go some way towards ensuring that the material and emotional needs of the elderly are met, in a way which facilitates active participation in the community.”

Where Māori and Pacific Island communities share a communitarian perspective when it comes to ageing and the role of the elderly in the community, Pākehā typically harbour an individualist perspective and resist the idea of foregoing active agency as they age. Instead of deferring to their children or caregivers, they cash in and move into retirement villages, rest homes and, ultimately, hospices.

Likewise in this worldview, children are individuals and Pākehā parents ‘don’t want to be a burden’ on them. Because of that, they are just as likely to isolate themselves and move away from their families (like in Home Land and Who Wants To Be 100?) as they are to move closer to their families.

There’s a fundamental tension here, and Kiata and Kerse note that this tension is often reflected in the care relationships between Pacific Island caregivers and Pākehā residents. Residents often felt that their caregivers were rough and uncaring, and many refused to form relationships with people whom they considered ‘hired help.’

That dynamic is reflected in Rose Kirkup’s play Unflattering Smock, which had a staged reading at Hannah Playhouse last September. In Unflattering Smock, the caregivers are Sāmoan, Māori, Fijian Indian, Cambodian and Filipino, while the residents we meet are all Pākehā. Kirkup, a former care worker herself, illustrates with dark humour the tensions between how the caregivers work and how residents receive their care. One resident, Mr Ivan, repeatedly refuses care, fights with the women of colour assigned to him and demands his care be provided by the sole Pākehā woman on staff, Lilly, ostensibly because she reminds him of his daughter.

These cultural perspectives also bleed into the media that we create, and that includes the plays that we put on stage. Too often, the old people we see on our stages are carrying Western colonial baggage, selling us images of old people as burdens: to be wrestled with, or whitewashed and ignored. Talofa Papa pushes back on that. Right up until its knife-twist of a final scene, Talofa Papa is critical of a cultural ideology that presents the elderly as a heavy load that families should feel free to ditch.

The old people we see on our stages are carrying Western colonial baggage, selling us images of old people as burdens: to be wrestled with, or whitewashed and ignored.

Papa’s good-natured audience interaction is key to that. Papa asks us to recite prayers and sing in Sāmoan; he shakes his head and leads us when we can't do it by ourselves; he asks his ‘favourites’ to perform Siva Sāmoa and talks about how Grandma would pass down Siva Sāmoa to her granddaughters. Papa centres us and provokes us to think on our relationships with our own elderly family members: whether we see them as burdens or value them as members of our family and community.

During Talofa Papa’s Kia Mau Festival season at BATS Theatre last June, one moment struck me with its beauty and generosity. Papa thanks us for turning up for Grandma’s birthday and opens the floor. He asks us to stand up and hold hands, which we do. He asks us to close our eyes and commune briefly with Grandma, speaking “with our heart,” which we do, and then he asks us to open our eyes. He points to us, one by one, and asks us to share our memories of Grandma.

Papa is, of course, asking us to share our own memories of our own Grandmas, to openly express our love and appreciation in a communal setting. The moment moves slowly, at Papa’s pace. In that space, Mita calls on us to acknowledge the roles that our parents, grandparents, guardians, caregivers and others have played in our lives, and asks to us to take up that role for them once they get older.

“The piece itself is about community and family,” Mita says. “We’re bringing people on stage, we’re having a blast. It’s about us all sharing a moment together.

“It was more about how do we get Papa what he wanted? Which is to see his family again.”

It is perhaps no coincidence that Talofa Papa and Still Life with Chickens were created by Sāmoan theatremakers. The images of old age we see on our stages are so often influenced by Western, individualist perspectives about how we relate to and treat our elderly population. They’re presented as emotional and capital burdens, sources of guilt and anxiety, tied down to homes and money they’re not using, or they’re dressed up as wacky adventure-seekers, because it would be far too distressing to actually think about them as old. The relationship between writer and character, and performer and character, is too often marked not by fa’aaloalo and alofa, but by condescension and fear.

As young people, we have an obligation to treat our elders as complicated, messy and extremely human, just as much as they have that obligation when they write younger characters. We fail to live up to that obligation when we use old people as vehicles for ironic comedy or sad, self-flagellating narratives about how difficult it is to get old (or, if we’re being honest, how difficult it is for us to look after people in our lives when they get old). We fail our elderly friends and family when we treat them like they’re homogenous, or, worse, like they’re vessels through which we can interrogate our own anxieties and fears about aging.

The relationship between writer and character, and performer and character, is too often marked not by fa’aaloalo and alofa, but by condescension and fear.

These narratives stop us from seeing elderly people as people, and when performed they produce dehumanising images of ageing: the shuffling, sad old man, the hyperactive old woman talking candidly about sex because isn’t that a funny joke, isn’t that just so unexpected? This isn’t about ‘respecting our elders,’ and all the baggage that statement brings, so much as it is about opening our stages to more complex, more empathetic, more community-minded perspectives. It’s about acknowledging the humanity of our elderly and showing care for them in how we represent them on stage. It’s about understanding our elderly friends and family better – and, potentially, preparing ourselves better for the inevitability of our own old age.

And hey, maybe, just maybe, this’ll stop Roger Hall being scared of us. Or maybe he’ll just find another reason to be scared. Could go either way, to be honest. But it can’t hurt to try.

Header image: From left to right, Raymond Hawthorne, Ray Henwood, George Henare and Mark Hadlow in Who Wants To Be 100? (Anyone Who's 99) (2007, Auckland Theatre Company). Photo credit: John McDermott.