Myth on Myth, Art as Autopsy

Natasha Frost on the work of Heather Straka and Marian Maguire

The accompanying catalogue to Heather Straka’s 2009 series ‘The Sleeping Room’ begins with an explanation of autopsy – what it is (‘a medical procedure to establishing the cause and manner of death’,), and the Greek words it comes from (‘auto’ – self, and ‘opsis’ – spectacle, likeness, or sight).

This makes perfect and literal sense in the context of the exhibition, where paintings of wilting flowers sit alongside images of squares of veined blue-gray human flesh; fingers; a weeping eye in its oyster-like socket, painted in her characteristically glossy, almost gauzy style.

Though the series suggests an autopsy, the conclusions of that autopsy are not put forward. They give no clear indication of a cause or manner of death – rather, they show a process of analysis taking place. Seemingly unfamiliar elements juxtaposed against one another suggest questions, rather than answers. What do the crumpled petals of the flower of Life Still No. 8 have to do with Life Still No. 1, a disembodied greying finger, hacked off at its second joint? Whose eye is that? What’s in that bag with the pink cord?

The process of autopsy is essentially the process of trying to work out an answer to a factually complex question. It’s also not unlike trying to find an intellectual response to a potentially emotionally fraught series of questions. I see elements of this elsewhere in Straka’s work – in her Asian series’ play between copy, originals, and the revisionism that lies in between, for instance; or in the highly controversial exhibition ‘Paradise Lost’, in which images taken from Charles Goldie and Gottfried Lindauer’s Māori portraits were reworked as Catholic saints.

In both of these, Straka took New Zealand symbols – the portraits, in the case of Paradise Lost; a recurring tiki brooch in the Asian series – and foreignised them, placing glowing Roman Catholic hearts over the breasts of Maori portrait subjects; pinning the brooch over and over again to the cheongsam of a 1940s Shanghai girl.

So why does Straka’s work instead lead me back to Canterbury, to compare Marian Maguire’s work to hers? Superficially, they do not seem to have much in common with one another: their styles are not similar, and neither are their techniques. But what they share – beyond the fact that both are white New Zealanders born almost exactly ten years apart; women; educated in Christchurch; artists – is a repeated return to cross-cultural imagery, where New Zealand iconography is placed in a foreign context, to striking effect.

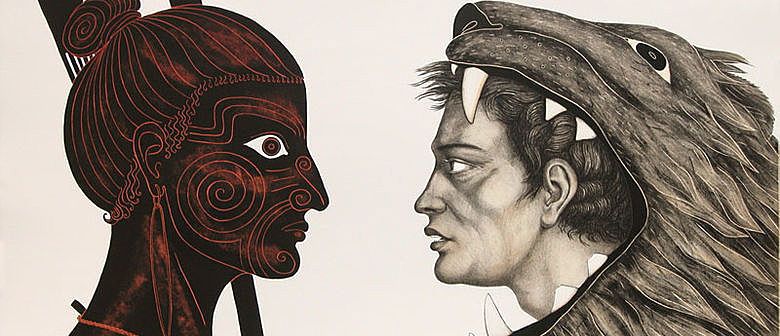

While Heather paints, and trained in sculpture, Marian works largely in lithographic prints and etchings, where the geometric blacks and whites, terracottas and browns of Ancient Greek vase painting depict Classical heroes alongside familiar figures from New Zealand history and myth.

Herakles comes to blows with a taniwha; elsewhere, a slightly startled Odysseus is being ‘orated at’ by James K Baxter. She calls this process ‘layering myth on myth’: a meeting of classical and colonial; two world-views stitched together with the same structural thread.

It is the way that ‘cross-cultural imagery’ comes into play in both of their work that is the most important link: both take New Zealand imagery and stretch it to foreign lands, foreign images, and foreign times. The process of doing so – of making familiar images strange – places these familiar symbols into a foreign context. Does doing so make it easier for us, as New Zealand viewers, to consider our own symbols: what they mean, and why they matter?

If ‘The Sleeping Room’ throws up the questions produced by a literal autopsy, these other series – Straka’s ‘Paradise Lost’, and ‘The Asian’; Maguire’s ‘Southern Myths’, ‘Colonial Encounters’, ‘The Labours of Herakles’ – show a similar methodical process of question-asking and analysis, of trying to work out the cause and manner of a incident. But instead of a fatality, they’re dwelling on the aftermath of a collision of New Zealand imagery, and the questions of history and representation that get caught in the fray.

In trying to talk about more difficult aspects of New Zealand imagery, the foreignisation makes intellectual puzzles out of emotionally fraught questions. Is this a trivialization, or a blessing? Theoretically, it could make it easier to approach them dispassionately. Even when it doesn’t, it perhaps forces us to address why we feel the way we do: take, for instance, the ‘Paradise Lost’ series, which provoked irritation, and, in some cases, anger, when Heather did not ask iwi for their permission to use the images. Immediately, questions appear about who the images belong to - not least because the original images themselves were have a difficult history beyond the regal autonomy they project on first glance.

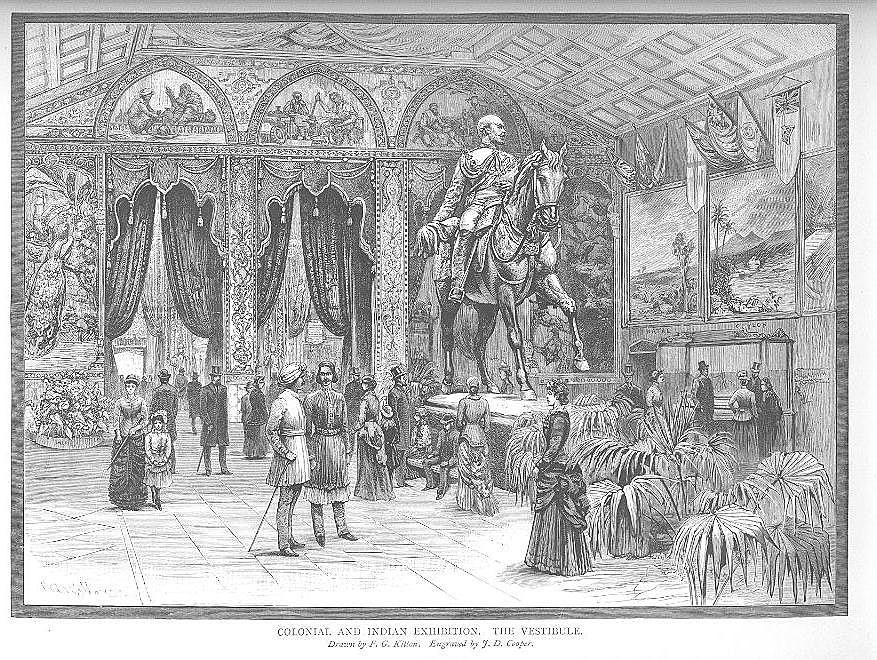

While it is true that Goldie and Lindauer were in many cases commissioned by the portraits’ subjects for the work, the latter’s subsequent exhibition at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 took a patron-artist relationship, more akin to anthropological examination.

On the one hand, the prominent subjects sought to have the work done; in many cases, Lindauer depicts a ruler and their land (at the height of settler confiscation, there is a certain irony in the fact that the land behind them, a sort of sfumato blur of ominous crags and clouds, is treated as the least interesting aspect of the portrait.). Even the lighting designates their high status.

On the other hand, they were taken out of their context and displayed within an exhibition of ‘the exotic’ in London’s South Kensington, laid up alongside ‘living exhibits’ of imported Indian craftsmen. In this sense, they seem to perform a similar function to taxidermy; a more accurate Horniman walrus, viewed by gawking tourists with no real knowledge of how faithful the representation might be. The attention to detail – of the feathers, of the moku – in this context begins to look less like a royal portrait, and more like a way to preserve a manner of life not likely to last much longer. This ties into a then popularly-held contemporary idea of social Darwinism, where ‘inferior races’ were to be well-documented, but would simply fade away when faced with a more robust European way of life.

At the same time Lindauer’s portraits were exhibited to acclaim, the accepted fact of the ‘dying Māori’ was generally lamented by pioneers, if not attributed to some kind of divine design (“Rum, Blankets, Muskets, Tobacco and Diseases have been the great destroyers; but my belief is the Almighty intended it should be so or it would not have been allowed, Out of Evil comes Good,” wrote one 1830 visitor to New Zealand) or seen as a kind of noble purpose (the long-defunct Wellington Independent wrote in 1868 that ‘we, in self-protection, must treat them as a species of savage beasts which must be exterminated to render the colonisation of New Zealand possible’.) Taken and exhibited a world away, the images had been appropriated even in their own age and within their own frames.

It could be argued that Straka’s re-use of the paintings gives them new life: rather than being the ethnographic representations of a dying race, the images show a people whose influence is still seen in New Zealand. The tattoos on their knuckles make them seem alive; they feel. Of course, the burning heart in Hui Love is a Christian symbol – the crucifix perched on top and the thorns that encircle it say as much – but it might also be read as an image of fervent living: the sitter’s spirit is ongoing, his regal power undiminished. Alternatively, do the Māori chiefs take on a cultural significance like that of Catholic saints?

Perhaps, as in ‘The Standing Room’, we don’t need to have answers to these questions: the most important aspect of this cross-cultural imagery; laying myth on myth; art as autopsy, is that it allows us to ask questions we didn’t know that we had, by placing images alongside each other that we didn’t know to be, or might not have thought of as, connected.

***

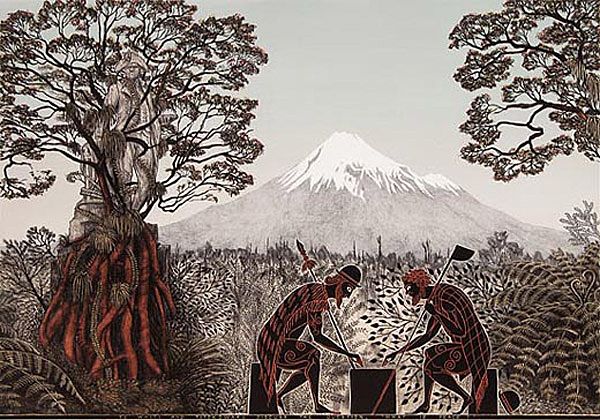

In Marian Maguire’s 2002 series ‘Southern Myths’, Ajax and Achilles make their way across an often hostile and forbidding New Zealand landscape. Ajax constructs a spindly pile of tinder at Manuka Gully in the Cambrian hills; Achilles is killed at Klondyke Corner, a campsite in Canterbury. He lies on the ground, an arrow sticking out from his ankle, as the battle rages on.

We only know the setting of the scene from the title, ‘The Death of Achilles at Klondyke Corner’ – visually, the figures are on a white plain, against black silhouettes of hills. It could be the landscape of Asia Minor – but if myths are untrue, what difference does it make where they take place -why not set it in New Zealand?, More to the point, how much do we really know about New Zealand’s history, especially before European colonisation – and how many ancient heroes, left undocumented, might have died in the valley or by the bush-clad hills of Klondyke Corner?

Questions about New Zealand myth and history come into focus further in Maguire’s series ‘Titokowaru’s Dilemma’, in which the Māori leader, passive resistance campaigner, and master tactician is seen in dialogue with Classical icons and iconography. For a man of contradictions – a devout convert who many believe had trained as a tohunga; an advocate of peace with a strong military background and education; someone who orchestrated resistance while resigning himself to the confiscation of land – he fits accordingly very neatly into Maguire’s lithographs. That contradiction becomes juxtaposition, while his position with those classical greats is one of equity, and sometimes even superiority.

In ‘The Dialogue of Titokowaru and Socrates’, Socrates’ eyes are fixed upon him. Titokowaru speaks, and Socrates listens. They both point at the same vase on the floor, which plays war off passive resistance, but here Titokowaru appears to be teaching Socrates a thing or two. Socrates is not necessarily a figure for the colonising individual: equally, he is not not a European coloniser. The questions remain open, the answers fluid and ephemeral.

This is not the first time that Titokowaru and Socrates meet: elsewhere, they stoke flames in front of Mount Taranaki and ‘discuss the question ‘What is Virtue?’ against a leafy background of ferns and shrubbery. Titokowaru is, as Elizabeth Rankin has also written, represented as a ‘thinking man’; while their cultural contexts may not be the same, he and Socrates are of the same profession. Titokowaru fits easily into a terracotta vase painting; Socrates looks at ease perched on a log in front of a fern. We know that Socrates existed; we know that Titokowaru existed – but both of their histories are blurred by unanswered questions, retellings and contradictions.

Seen in profile, deep in conversation, we find ourselves asking quite how different they both are; what relation they have to each other; whether we value their thoughts and contributions in the same way – and if not, why not. In autopsy, we ask questions about a personal history, and what has happened: here, we ask questions about how we think about what never happened at all. They are less different than they seem.

If autopsy is a way of working out the manner of death, embalming can be seen as a cosmetic way of denying that death’s visceral, unpleasant reality: of working the fluid through the veins of the body to give the corpse a glowing, life-like appearance, with a view to giving family members a pleasant viewing experience. Following embalming, the theory goes, the person should look almost as if they were able to sit up and say hello. The disruption or violence that we associate with death is invisible. So is it, stylistically, with both Straka and Maguire’s work.

In Straka’s painting, there is a total absence of any brush-strokes; Maguire’s lithographs also seem to have emerged fully-formed – her classical figures, even while they navigate its strangeness, look totally at home in a New Zealand landscape. The stitches between the composite images seem almost entirely absent. In the 2009 catalogue to Straka’s series, those ‘attractive glossy surfaces’ were said to ‘give death a palatable veneer, and are meant to engage, rather than repulse, the viewer.’

Is this stylistic decision a conscious decision to ‘smooth over’ the difficult questions? I would argue it actually makes their appearance all the more unexpected and striking, for they demonstrate the tension between an otherwise visually ‘unified’ piece of work and its dissociated elements or images.

To take Straka’s Asian series as an example: in the vast majority of the Asian series, the central figure wears a tiki brooch. In at least one of the paintings, however, a seemingly innocuous anchor brooch replaces it. She leans on a milk carton, on which is stenciled, in blood red against an otherwise monochromatic painting ‘Whipping Cream’. The words appear to have been printed out – the typefaces are standard Microsoft issue – and stenciled on. They are the most prominent part of the painting.

Suddenly, the anchor brooch, replacing the tiki, falls into context: it’s the logo of the Fonterra-owned dairy brand, Anchor. Is Fonterra really as meaningful a symbol of New Zealand identity as its indigenous people? For some, certainly: Fonterra already operates a number of industial-scale dairy farms in mainland China, promising to operate 30 across the country by 2020, employing hundreds. Before that, a Chinese company it owned a 43% share in was involved in an adulterated milk powder scandal that killed as many as six infants. The subject looks out from the frame, unsmiling and enigmatic.

In Maguire’s ‘Herakles Writes Home’, Herakles’ club leans against the wall, while his lion skin is thrown about the shoulders of his chair. His dog sleeps by the fire, while he bends over his desk, in the process of writing home. A tourist figurine of the Venus de Milo sits on the mantelpiece. Caught in the act of some ‘off-duty’ hero time, he is a colonizer, but he also a man caught far from home, in a foreign place where his trinkets are all he has to connect him to his origins. The stripped landscape out of his window shows Mount Taranaki in the distance, as well as what appears to be a vegetable garden or farm in construction.

Herakles the colonizer is a man trying to make a home for himself on the other side of the world – his Greek-Maori dictionary says as much – but the action of doing so raises its own questions; whether the land outside is his for the stripping; what he is doing; whether he is lonely. Though he is said to be writing home, it is not obvious from the myth to whom he would be writing, so much of his family being dead or estranged. The things he is famous for – his military capacity, ingenuity, courage – seem cast off with the lion skin, and he looks at once very alone, and very out of place. This outwardly European figure does not sit easy against the landscape; you wonder whether he knows why he is there at all.

These questions are for a New Zealand audience, asked by New Zealand artists. In a multicultural country with a very short written history, which belies the length of its human settlement, it pays to find ways to ask questions that we may not know we have about myths we may not even think of as myths. Heather Straka and Marian Maguire help ask, if not answer, these questions. They each embark on the strange and unfamiliar process of making the known foreign – and once they’ve done so, we’re left to piece together the ‘cause and manner’ of New Zealand iconography, unpicking the stitches, and facing what’s real.

Marian Maguire's official site. Heather Straka's profile at Trish Clark Gallery.