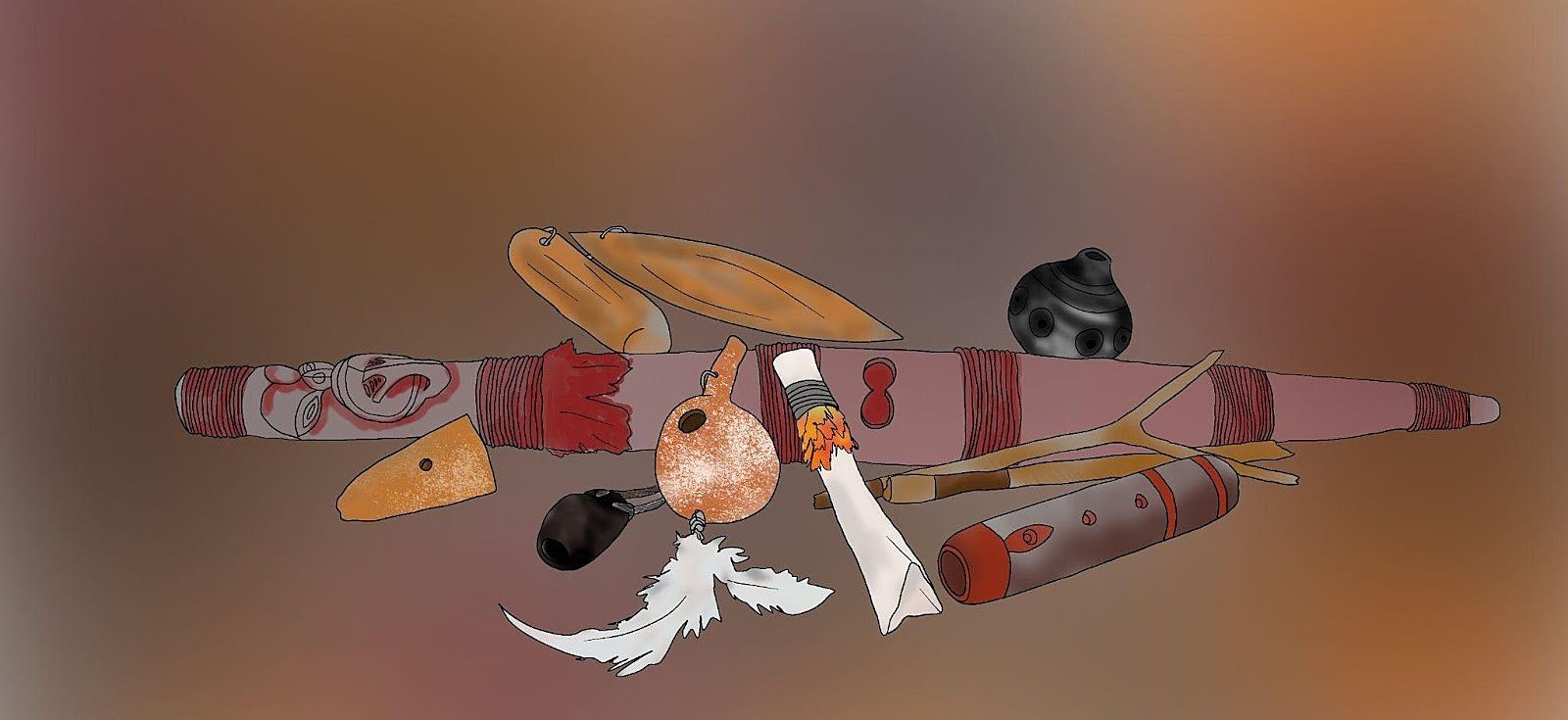

My Taonga

Ana McAllister calls to the taonga pūoro in her collection.

Ngā Kata ō Kōkōwai, wooden kōauau.

Ngā Kata ō Kōkōwai, the laughter of kōkōwai

My tuakana used to tell me to laugh in the face of my enemies. My mother laughs in the face of a Karen at Countdown and then goes home to have a little tangi. It’s all about the taurite. My kōauau was the first taonga I owned. Humble small beginnings. I adorned her with kōkōwai, the awa o ngā atua. Drew a tara on her. And made her sing. Though her song sounds sad, I can sometimes hear the hyena cackle of the aunties. All the aunties. All the way back to the beginning of time, Te Kore. The aunties of Te Kōre cracking up at the thought of Io thinking he’s hot shit. The laughing through the crying, it’s all very urban Māori.

Te Pūkaka ō Hine Moana, bone kōauau.

Te Pūkaka ō Hine Moana, the leg bone of Hine Moana

Te Pūkaka ō Hine Moana came to me at the shoreline. Hine gifted herself to me, I humbly received her koha. Hine Moana is so often forgotten nowadays. Like many wāhine, her husband's name has carried across the wind. But me and Hine Moana, we are well acquainted now. We regularly meet at Saint Lukes Mall for a coffee and catch up. She tells me the tales of the world’s birth and her long, white hair jumps with her hiccups of laughter. She asks me about my mahi, always questioning, “E kare, why don’t you ever look after my manu?” I push back and ask her when she’ll send me one. She gives me her leg bone instead.

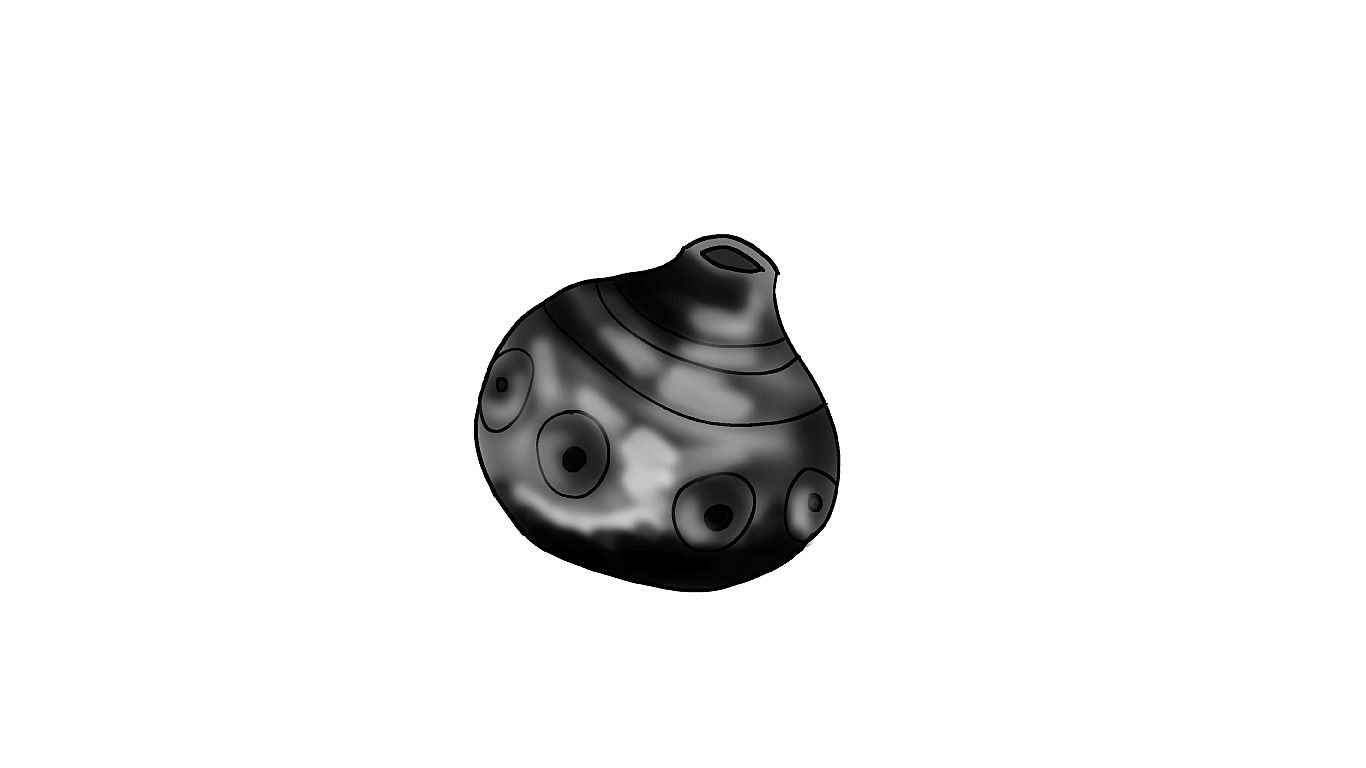

Hinepūtehue ō Hā, nguru made from the neck of a hue.

Hinepūtehue ō Hā

When Hinepūtehue took in the anger of the atua, and returned peace to te ao marama, she became a hue. Now I hold Hinepūtehue in my hands and I whisper secrets into her. I whisper the acts of anger performed against me and ask that she returns to me with peace. The karakia bounces around the puku of Hinepūtehue; I put her to my ear to hear the advice. And she gently whispers, “This Pākehā is not worthy of our forgiveness, I will send a pānui to Whiro, rest now.” I sleep well, cuddling Hinepūtehue, knowing that she has taken my hūneinei away for at least the night.

Pūkeko, poi āwhiowhio made from hue and pūkeko feathers.

Pūkeko

Pūkeko flick their tails up with a flash of white when they are hungry, horny, angry or scared. They mate for life, but fuck other manu. Their meat is tough. Best to be stewed for a long, loong time. Takes time to loosen up the flesh. Fling your poi āwhiowhio in the sky and circle it around like a chirping halo. This action, when repeated, will toughen your meat up. Meaning that when someone comes to consume you, they must put in the needed time and effort to tenderise your flesh. Like the pūkeko, I have always been told my meat is too tough. Too thick of a skin. Too angry of a mauri. I flick my skirt up like my Scottish tīpuna and expose my white bum like a pūkeko. I am hungry, horny, angry and scared all at once.

Whatu, nguru.

Whatu

When we were kids, we’d eat rocks. Chuck them in our mouths, wet them with our tongues, and swallow them whole. Yummy! we’d say, walking past the horses for the kids with special needs. I dreamed of the power that rock would give me. Imagined it travelling down my oesophagus, slowly disintegrating and the muscles pushing it down. I thought about the cool shit I must be able to do now. Like fly, or read minds. I told my friend that once I was all-powerful, I’d leave this shithole. After all, what’s a superhero gonna do in Tokoroa. Now that I’m 25, all those stones had to be cut out of my puku. The tohunga sliced from my chest to my pubes. Dug around for a bit. Then pulled out this beautifully formed nguru. Its song is a tangi for a childhood now long gone. And I wish I could go back to Tokoroa and just be normal. I don’t want these powers anymore.

Ngā Rara ō Au, wooden pākuru.

Ngā Rara ō Au, the ribs of me

I have never once slept under the ribs of my tīpuna. Unable to claim that simple rite, I instead grew up sleeping under the ribs of foreign trees. The Norfolk pine grows much better here than it does in Norfolk. My parents thought the same. Took me to the conditions for optimal growth. And I have grown, on foreign soil, as a guest. Flourished on a whenua far from my own. But I do miss the ribs of my tīpuna. So in a half-hearted attempt to build my own whare, I took out two of my ribs, both from the left side so I would walk hunched to one side, the imbalance making me walk in circles. I placed my two ribs over my bed and tied them together with hemp string from The Warehouse. But every night, they slipped apart and the rain got through. Ngā tangi o Ranginui for the love of his life. These ribs of mine simply did not make a strong enough shelter for me. So I took them, one night, and tapped them across my waha as I asked for forgiveness. And Ranginui cried with me. And we cried all night long.

Te Tio ō te Kaihopu, stone manu karanga.

Te Tio ō te Kaihopu, the (bird) call of the catcher

I am Kaihopu ō ngā manu. Ka karanga au ki ngā manu, and they come to me in flocks. Their wings beating against their bodies create a thunderous roar. Their mass blocks the sun from my eyes. Covered underneath their darkness. I call to them and one by one they drop to my feet. The tūī calls back to me in my tipuna matua’s voice. The pīpīwharauroa arrives freshly from Papua Nūkini. The kea and kākā are reunited once again, brought together by my karanga. I rejoice at the taonga I have, and they rejoice at the whakaute I have for them.

Tā te Manawa, wooden pūrerehua.

Tā te Manawa

I once had a lover whose cry would sing at the lowest hum, almost a vibration without an audible sound. Her name was mamae and, man, she felt pain. It is said that when you play a pūrerehua, your wairua moves up the string whirling above your head and out through the instrument to everyone who can hear it. So I would play for mamae, day after day, night after night. Trying to gift my wairua to her. One day she said to me, “Why do you play that pūoro constantly?” I replied, “My love, I want to give my wairua to you, tā te manawa.” She looked at me, puzzled, and said, “You’re making me mamae!” I did not know that under the shadow of Taranaki, pūrerehua is called mamae, and I was the one calling her mamae.

Ngā Tangi ō Kōkōwai, wooden pūtōrino.

Ngā Tangi ō Kōkōwai

Unclench your jaw, breathe in, breathe out. Lately my back has been tight. I wake up at 3am every night in pain. There are men in my dreams who chase after me down dark alleys. They’re white and pale like patupaiarehe, but not. They aren’t mischievous, but angry and violent. They frighten me, and even though I walk keys between knuckles I still don’t put in my headphones. I had these flash security cameras installed, but I just ended up using their audio function to say thank you to the man delivering my food. I have cried every night for the past month, and now I’m so tired that sometimes I see the men following me while I’m awake. I sit on the last carriage of the train with my back to the wall. I watch them, watching me. Now that I lie awake all night, I have started watching The Blacklist. It’s not as good as I remembered. I decided I needed more protection than just the cameras, so I got a pūtōrino made. I sent the carver some kākā feathers to adorn my new lover with. And without my request, the carver covered her in kōkōwai, like Ngā Kata ō Kōkōwai. I got her, and I cried and cried and cried. I have not stopped crying since. I kiss each waha with tears streaming down my face and crying while she sings. And I wonder if the crying is enough to keep the white men away from me. But at least, now, she sings me to sleep.