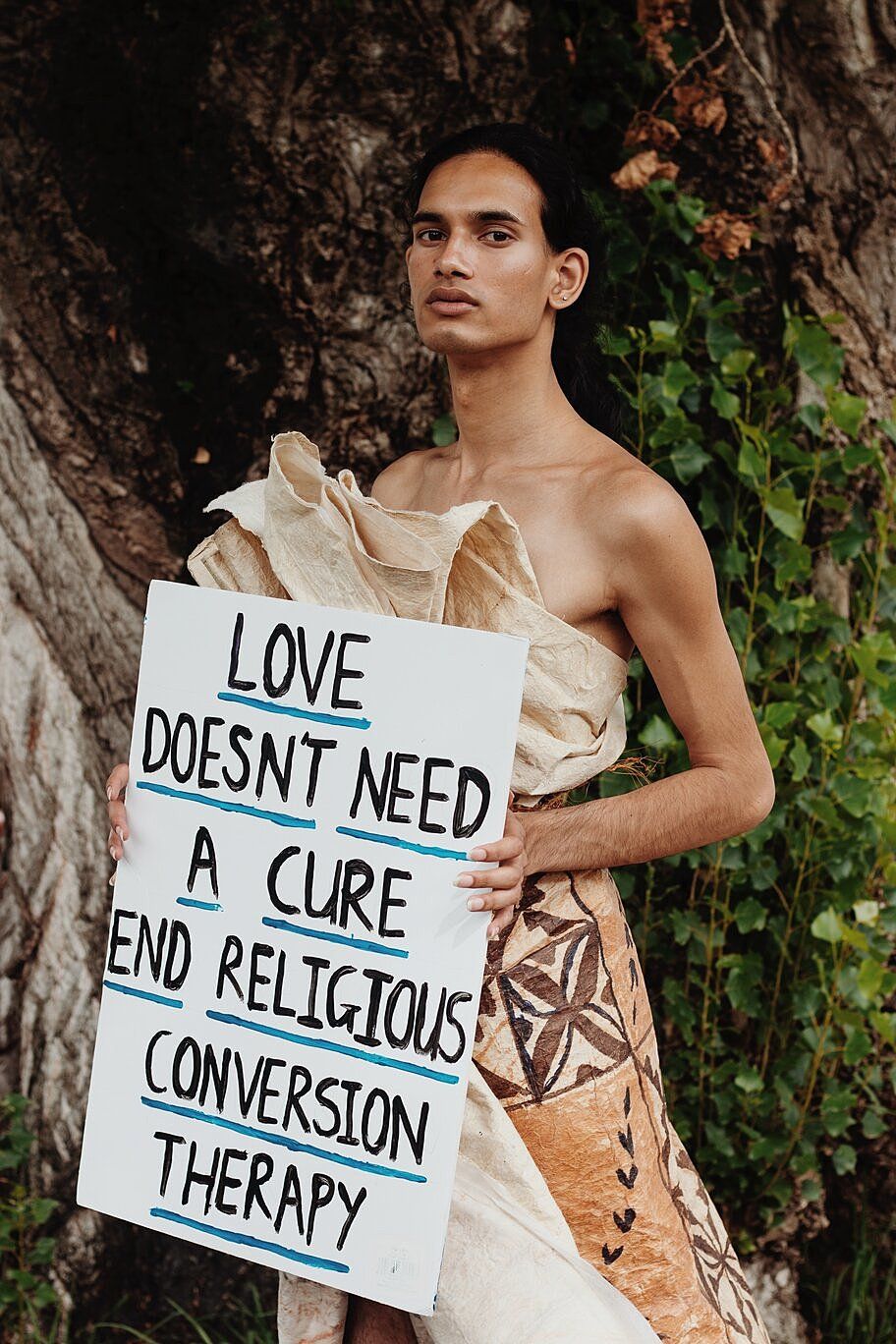

My Queerness is Not an Evil Spirit to be Dispelled

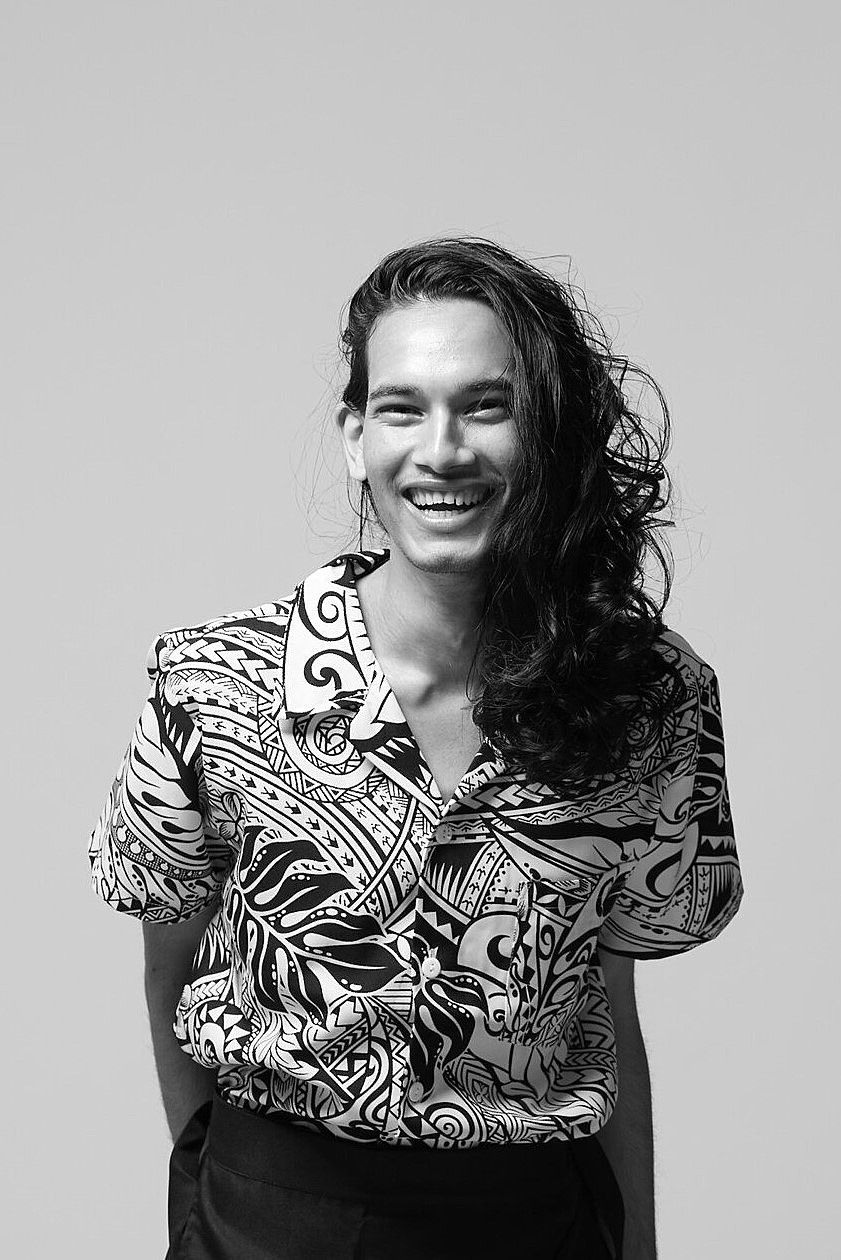

Today Shaneel stands before the justice committee to make an oral submission on the Conversion Practices Prohibition Legislation Bill. This is their story.

Content warning: trauma, colonisation, conversion therapy, suicide

Months before an ethnic coup, I was born in Fiji to an iTaukei (Indigenous Fijian) and Girmitiya family. Girmitiya were the Indian slaves, brought to Fiji by the British colonisers to work on the sugarcane farms. I was lucky to be born into a prestigious family. My grandparents were well respected in our village; they led the temple, cooked, sang at weddings and helped build many houses. They earned their position as elders of the village through years of service.

It was clear to others that I was Queer before I understood it myself. Maybe it was because I carried my hand in the ‘is he… you know’ style. My Queerness wasn't ordinary. While most boys were entertained by rugby, I would sew dolls’ dresses with my mum's best friend's daughters. Years of colonisation and criminalisation forced my Queer ancestors into hiding, so it was time for my ancestors to live their lives through me when I was born. I played with dolls, painted my nails, danced, and for every boyfriend, I made ten girlfriends.

My Queerness started to hurt my grandparents’ standing in the community – it was weaponised against them. In every dispute, someone would bring up my Queerness to invalidate and humiliate my family. The years of service meant nothing if my family accepted me. I was often asked to stop ‘acting like a girl’. I didn't understand what that meant, but I learnt that I needed to stop being me. I tried to carry myself more conservatively and failed. I was overtly Queer. There was no hiding or fix for me.

I tried to carry myself more conservatively and failed. I was overtly queer. There was no hiding or fix for me.

*

*

In my village, there was one openly Trans woman. The villagers would yell insults at her and sometimes physically hurt her. I watched this as a child and learnt this was about to be my future. It wasn't only about safety; my family's love wasn't promised either. The way people treated openly Queer people convinced me that I could only be safe, happy and loved if I changed.

Fijians are a collective community. Elders in the village were allowed to care for all children. Soon enough, some elders in the village took advantage of this and started to try to pray my Trans away. The collective nature of my community hid my conversion therapy from my family. It was taboo to speak about Queerness in Fiji. There were no words in our vocabulary for Queer identities, but there were many derogatory terms.

The elders tried to free me from the evil spirits that were making me Queer. I was kept away from the boys and from the girls to stop me from becoming Queerer. My Queerness was treated like a virus, if not an evil spirit. My conversion therapy isolated me. I was harmless. I did not want other children to be Queer. I just wanted to survive.

My queerness was treated like a virus, if not an evil spirit.

*

I was at war with myself. The elders promised me that I would burn in hell for the rest of eternity. They assured me that my family would disown me. How could I not want to change? Many people continue to argue that Queer people can consent to conversion therapy. The reality is that no one can. Our entire belief system convinces us that being Queer is sinful and worthy of punishment. Conversion therapy is never a choice for queer people because refusing to convert means saying goodbye to everything we have ever known and loved.

Every story of conversion therapy ends with a Queer person questioning whether life is still worth living. I am lucky I chose to stay. Many don't.

Religious leaders have weaponised the relationship Queer people have with God and manipulated us into thinking God will hate us if we don’t change. God doesn’t care if I am Gay or Trans; being a decent human will suffice. As for these religious leaders, they pushed me into a life of pain and misery, and God will never forgive them for it.

At 21, I am ready to rule hell. If all queer people are going to hell, then that's where I want to be.

*

I moved to Aotearoa in 2014. In the summer of 2017, I was volunteering at Middlemore Hospital when a church leader walked up to me and offered to pray my Gay away. I refused, so he looked at me and said, "It's hot, but do you know what's hotter? Hell." I was once again being promised hell if I didn't suppress my queerness. At 17, going to hell was a frightening idea. At 21, I am ready to rule hell. If all Queer people are going to hell, then that's where I want to be.

I couldn't believe that conversion therapy was still legal in New Zealand. In 2018, the Young Greens, Young Labour and Amanda Ashley petitioned the Government to ban conversion therapy. In response, Marja Lubeck introduced a member's bill into Parliament. That bill was never drawn. In 2019, I stood up in Parliament and demanded they ban conversion therapy. A year later, the Labour Party made it an election promise. The Government bill to ban conversion therapy is with the justice select committee now.

I was expecting most churches to oppose the ban on conversion therapy, and a significant number of them did. I was filled with anxiety when the biggest churches in New Zealand started organising to make submissions to the select committee against banning conversion therapy. It felt as though history was about to repeat itself. But things changed when numerous other churches spoke up in support of banning conversion therapy.

I will not allow this practice to continue.

*

I have loved, and I have been saddened by, seeing parents’ messages to their children supporting a ban on conversion therapy. I love it because we all deserve parents who love us, and I am so happy that some children have that. I am sad because I don't have that, and I know so many Pacific children who don't. Nothing can fill the void for Queer children who’ve been disowned by their families.

Colonisation has significantly shaped my life. It has stolen my community and my family from me. No amount of technology can make up for all the love I never received, and the time I never got to spend with my community. I am enraged at colonisation for taking away so much from the children of the Moana.

Colonisation was the largest-scale conversion therapy of Indigenous peoples. It violently stripped us of our Queerness and conditioned my people with homophobia and transphobia. Conversion therapy severed my ties with my ancestors. Banning conversion therapy is decolonisation. Restoring the place of Queer people is Indigenising.

Conversion therapy is not about praying the Gay away or fixing the Trans. It is about psychologically and physically torturing the most vulnerable to death. I survived conversion therapy. As a survivor, I have to protect Queer children who will suffer the same consequences. My Queerness became aversive to me through constant association with pain and immorality. I will spend a lot of my adult life fixing parts of me that conversion therapy broke, but I will not allow this practice to continue.