My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak: Bringing back Bollywood

Brannavan Gnanalingam revisits his Bollywood awakening in light of Ahi Karunaharan’s latest play, My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak.

Brannavan Gnanalingam revisits his Bollywood awakening in light of Ahi Karunaharan’s latest play, My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak.

In 1990s Aotearoa, it was initially difficult to find Tamil films or Bollywood films to watch. For Sri Lankans like my family, Indian cinema dominated. People went on shopping sprees whenever they went back to Sri Lanka or India. What arose were almost black-market video stores, where an aunty or uncle down the road accumulated a vast treasure trove of VHSs and would share the videos around the community. It was there that my parents would get their films: Bollywood classics, devotional films, cheesy genre films, and some of the latest pirated hits. But they weren’t anything I ever watched – desperate to fit in in Aotearoa, I was never interested in watching what I thought were the same old moustachioed villains getting their comeuppance in films, featuring both extended and unnecessary fight scenes, and badly dubbed, cheesy romantic subplots.

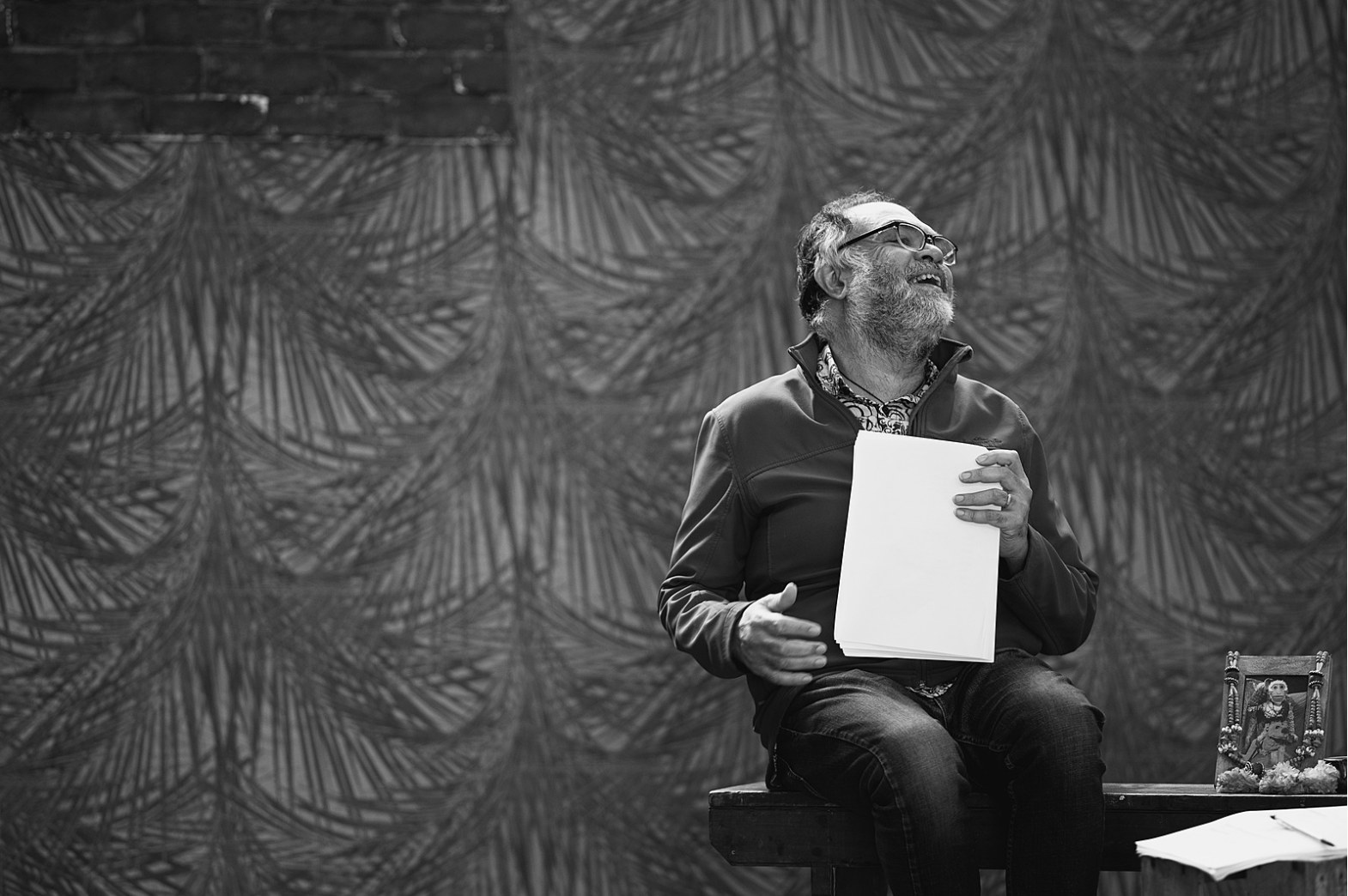

Playwright and director Ahi Karunaharan’s newest piece, My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak, pays tribute to Bollywood cinema. It’s set in Bombay/Mumbai in 1975, at a point in time when the film industry (and Indian society more generally) was starting to undergo some seismic shifts. Karunaharan, unlike me, grew up a huge Bollywood fan. Born in the UK, he spent part of his childhood in Sri Lanka in the 1980s. He distinctly remembers watching the classic 1975 film Sholay with his uncles. “Sholay wasn’t a massive hit, but it had a cult following. The music was massive. The film stayed with me from Sri Lanka. That’s the memory I carried with me from Sri Lanka.”

Karunaharan acknowledges that this love of Bollywood put him at odds with his Lankan friends in Aotearoa, most of whom followed my trajectory and rejected their parents’ films. Karunaharan says, “I don’t know how I got sucked in. They were really violent, really melodramatic. I’d been fed, and lapped it up and it was always part of my growing up. For a lot of my friends, it wasn’t until a retrospective, or in hindsight [that they came to appreciate Bollywood].”

And it’s true. I only started properly watching Bollywood at university, when I was forced to teach it at Victoria University in an Asian Cinema paper. My initial reservations disappeared and I grew to love the sudden tonal shifts, the music, the sheer exuberance and joy – and the multitude of other Bollywood films that broke my stereotyped view.

Karunaharan also stood out to me, growing up. I remember visiting his home as a child, and instead of playing cricket like we did at most other Lankan houses, Karunaharan put my sister and me through the paces of theatre sports. Karunaharan was a couple of years ahead of me at Victoria University’s Film and Theatre School, so his trajectory towards the stage didn’t surprise me. Unlike many of us Lankans who also dabbled in the arts, Karunaharan went all in. His career has been uncompromising and single-minded. Karunaharan admits that he felt a responsibility, as one of the few Sri Lankan writers, to “carry all of the community’s story. I don’t think that’s an expectation [from others], that’s an expectation on yourself.” His focus has been to present South Asian stories on stage for us (and the rest of Aotearoa) to watch, and in doing so, he hasn’t compromised his ambition or his values. For someone like me, he has been an absolute hero and trailblazer.

It’s easy to see why this era would be fertile ground for Karunaharan. Bollywood cinema largely had a template that had been well-worn for decades. However, cinema in much of the rest of the world in the 1960s and 1970s started to expand: auteurism, anti-establishment politics and post-colonial ideas were feeding in, particularly in countries that were now a generation on from independence.

During the 60s and 70s, immigration from South Asia to Western countries picked up apace, and global chains of communication (and markets) were spreading within South Asian communities. The Tamil diaspora was also starting, as ethnic tensions in Sri Lanka continued to simmer. Similarly, the late 60s was also obviously a time for Western pop-cultural interest in the ‘East’, where the likes of The Beatles and psychedelia mined Indian cultural traditions.

The script of My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak is fast and witty, with the rapid-fire banter of the likes of Gilmore Girls. However, the filmic references feel lived in, they don’t feel gratuitous or showy, and they add a considerable amount of intertextual depth to the narrative

Some of the more well-known traditions vividly expressed the push-pull effect of an increasingly globalised filmic world. In particular, Blaxploitation, 1970s Hong Kong action cinema, Italian genres like giallo and spaghetti Westerns merged the genre conventions of Production Code era Hollywood with the politics and anti-heroes of post-Production Code era Hollywood. Anti-heroes became heroes and the powerful became the villainous. There is also a tension within Hollywood, which was itself undergoing a renaissance. The year 1975 is of course when Jaws was released, a moment when Hollywood realised spectacle and Boomer auteurism could be particularly profitable.

One of the key figures in Bollywood’s similar shift was Amitabh Bachchan. He was the ‘angry young man’ of Bollywood cinema (think 1950s Brando in the way he combined rugged good looks with a general insouciance) and films like Sholay did much to change expectations of Bollywood leads. Sholay was inspired by Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns – and it must be said, Clint Eastwood’s films with Leone were huge in South Asia.

The script of My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak is fast and witty, with the rapid-fire banter of the likes of Gilmore Girls. However, the filmic references feel lived in, they don’t feel gratuitous or showy, and they add a considerable amount of intertextual depth to the narrative. The tension of Kamala and Roshan’s relationship is heightened by their film references, their Bollywood-versus-Hollywood patter. Veteran actor Ranikumari harks back to Norma Desmond from Sunset Boulevard, someone who is surrounded by ghosts. The script also showcases Karunaharan’s considerable filmic knowledge in a way that will be particularly satisfying for Bollywood buffs.

While the script is light and breezy, it would however be a mistake to assume the narrative is superficial. Karunaharan has not been afraid, throughout his career, to tackle big, political issues that have affected South Asians: from the effects of the devastating Boxing Day Tsunami and the Sri Lankan Civil War to colonialism and Indira Gandhi’s Emergency. My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak makes patently clear the split personality of being a diaspora and/or minority artist. One of the tensions that exists is the extent to which you need to express your ‘South Asianness’ in your art – the difficulty of toppling the power imbalances that for decades have told you that your art is cheesy or worthless.

More broadly, there is also a clear competing tension between nostalgia and innovation for generations that are trying to supplant the previous one. The characters Ranikumari, Manjit and Roshan are almost stuck in the past, the way things used to be. Karunaharan, by setting the play in 1975, creates a fascinating dynamic as a result.

With the distance of time, he’s able to pay tribute to some of the pioneering voices, the people who gave South Asians a global artistic blueprint. But he also cautions against being too wedded to a mythical past.

With the distance of time, he’s able to pay tribute to some of the pioneering voices, the people who gave South Asians a global artistic blueprint. But he also cautions against being too wedded to a mythical past (and it’s certainly ironic that many of the revolutionary 70s Bollywood stars are firmly in the camp of India’s current lurch to ethnonationalism and nostalgia).

Through this tribute, Karunaharan ‘fills in the gaps’ of the past, bringing to life stories of how we, South Asians, have been shaped. These are stories that have barely been told on stage before in Aotearoa. It allows him, as he describes, “to bring our families to the now by acknowledging the past. There’s distance that allows me to have those uncomfortable conversations.”

Karunaharan maintains a masterly control between a lightness of mood and heavy themes. For all of the darkness hinted at above, My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak is also immensely pleasurable. From the humorous script, to the ‘filmic’ approach with the lighting, to the music and dance, and its gleeful breaking of the fourth wall, there is much to enjoy. Drawing from a cinema that unashamedly wears its emotions on its sleeve, My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak takes pleasure in ephemeral moments, in big foolish gestures, and ultimately in staying true to oneself.

Silo Theatre’s My Heart Goes Thadak Thadak runs from 21 November – 14 December 2019 at the Q Theatre – Loft. Tickets available here.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Silo Theatre and appears in the show programme. Silo covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.