What's left of the Mugabe way?

Where are the traces of Robert Mugabe? Murdoch Stephens looks at public spaces in post-Mugabe Zimbabwe.

Where are the traces of Robert Mugabe? Murdoch Stephens looks at public spaces in post-Mugabe Zimbabwe.

Lurking beneath the supreme obedience accorded to despots and dictators must be a paranoia that as soon as they are deposed or die, their legacy will be wiped out.

In the last two years of Robert Mugabe's reign in Zimbabwe his interest in his own legacy became obvious. What kind of dictator spends 37 years without making sure his image will endure?

In 2016 two Mugabe statues, one reportedly 10m tall, costing $5 million were commissioned from North Korea. They have not yet arrived due to difficulties around sanctions on Pyongyang and now that Mugabe has been deposed, it is hard to know what will become of them.

Just five days before his ousting Mugabe unveiled the new branding of the Harare International Airport cum Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport. The signs pointing in that direction from central Harare are suspiciously ad hoc, as if Mugabe thought one more show of absolute dominance might rescue him from the coming coup.

Will anything remain of Mugabe’s influence in a hundred years?

As part of a journey from the southwest to the northeast of Africa I spent two-weeks, from Christmas Eve into early January, traveling across Zimbabwe, observing the dust settle on the new government. Even though Mugabe was stripped of power in November a month before I arrived, I still expected to see at least some semblance of his rule. While statues might be toppled, books burnt and portraits torn down, other symbols like faces on currencies, or the names of roads and airports take a little longer to disappear.

Anyone travelling through former Soviet countries will notice hammers and sickles remain in high-up architecture or iron fences, both of which have survived due to the cost of replacing them.

In Ulan Ude in Siberia, for example, an enormous head of Lenin remains in the main square. When I asked locals their thoughts, they replied that it was part of their history and should not be taken down. Indeed, the year in which I asked also marked the 100th year since the ascendency of Lenin at the head of the Bolshevik’s October Revolution.

But will anything remain of Mugabe’s influence in a hundred years?

Given the relatively smooth transition of power – a military coup, not of the state, but of the leadership of a political party – maybe Mugabe’s complex legacy would be enough for him to be protected as a kind of historical relic. Surely part of the softness of the coup and Mugabe’s treatment afterwards can be attributed to his age. While we might fear a toppled 60-year-old, his 93 years make a gentle retirement seem more likely.

Mugabe had always been a fascinating figure to me. As a young New Zealander, I knew more about Zimbabwe than other African countries thanks to the regular cricket matches between our two countries. I talked with friends who'd left Zimbabwe at various points in their lives, and many had strong views against Mugabe – he had forced their white parents from their farms, businesses and communities after all.

In contrast to the single-minded animosity, I was fascinated by the views expressed by Māori Party leaders Tariana Turia and Pita Sharples in 2005 that showed a reluctance to unequivocally demonise Mugabe. This made me consider Mugabe again. How difficult it must be to overthrow the legacy of colonisation and to do so without challenging the underlying economics of land ownership. I looked further back at the history of the country and saw that Mugabe had once been the great hope around the world for a free and strong Zimbabwe.

I looked further back at the history of the country and saw that Mugabe had once been the great hope around the world for a free and strong Zimbabwe.

Despite the complexity of his task, it was Mugabe's comportment that made Mugabe stand out. I've never been able to explain why he seriously – going where hipsters fear to tread – stuck to his toothbrush moustache. Surely, he wasn't so hubristic that he believed that he could break that facial hair from an association with Adolf Hitler. I had always wondered what sort of double bluff that represented or whether he was quite happy to have the comparison made? I suppose a dictator's mind works differently than your average young New Zealander.

Before even arriving in Zimbabwe, I had many reports from Zimbabweans in neighbouring countries. In Namibia I spoke with James, a tour guide and one of the millions of Zimbabweans who are migrant workers and refugees in countries neighbouring their homeland. When asked his thoughts on the Zimbabwe coup d'etat, he replied with gusto: “What do I think?! We are celebrating our independence!”

While there is a tentativeness about both what happened in the coup and whether Mugabe was actually a party to it, there is only jubilation about the prospects ahead. For James, moving past the 37 years of Mugabe's rule was the equivalent to the 1980 independence from white rule. That 1980 independence followed the 1965 independence for Rhodesia, claimed from the United Kingdom by a white minority government.

It is still anyone's guess whether the newest form of independence marks as substantial a change as that which bought Mugabe to power in 1980, or whether – just like the 1965 independence – it is the maintenance of the same government sans it's head of state.

On top of that, there are plenty of rumours still swirling. Perhaps Mugabe orchestrated the coup to keep his wife from taking power?

Or maybe the ruling ZANU-PF really did force him out. But if they did, why grant him so many privileges after being ousted. Not only did he receive $10 million, but his business interests were to remain untouched, he was granted diplomatic status and his family was granted immunity from prosecution for crimes while in office.

While James was optimistic, a young white labourer I met on the train from Victoria Falls to Bulawayo lacked any hope for a new Zimbabwe.

Francis, who had been visiting his girlfriend who worked in the tourist hub, was thoroughly tired of his life in Zimbabwe. His sole desire was to leave; England was his first choice.

Francis had plenty of stories of discrimination and his rhetoric was equivocal: there was racism on both sides, he said, and in particular in the military. He had hoped to serve, but discrimination made him decide to remain as a civilian.

I listened to his story with an open mind, though as the sleeper cabin lightened in the morning my eyes were drawn to a home-made stick-and-poke tattoo on his arm that looked like a three-sided swastika. I googled the image and found it was a triskelion – in this case a neo-Nazi right-wing Afrikaner Resistance Movement. I kept trying to think of a reason this boy would have this tattoo – he looked no older than twenty-two – but ultimately, I had to admit that despite his attempts at sounding even-handed, he had at one point in his life thought it a good idea to have an apartheid symbol tattooed into his flesh.

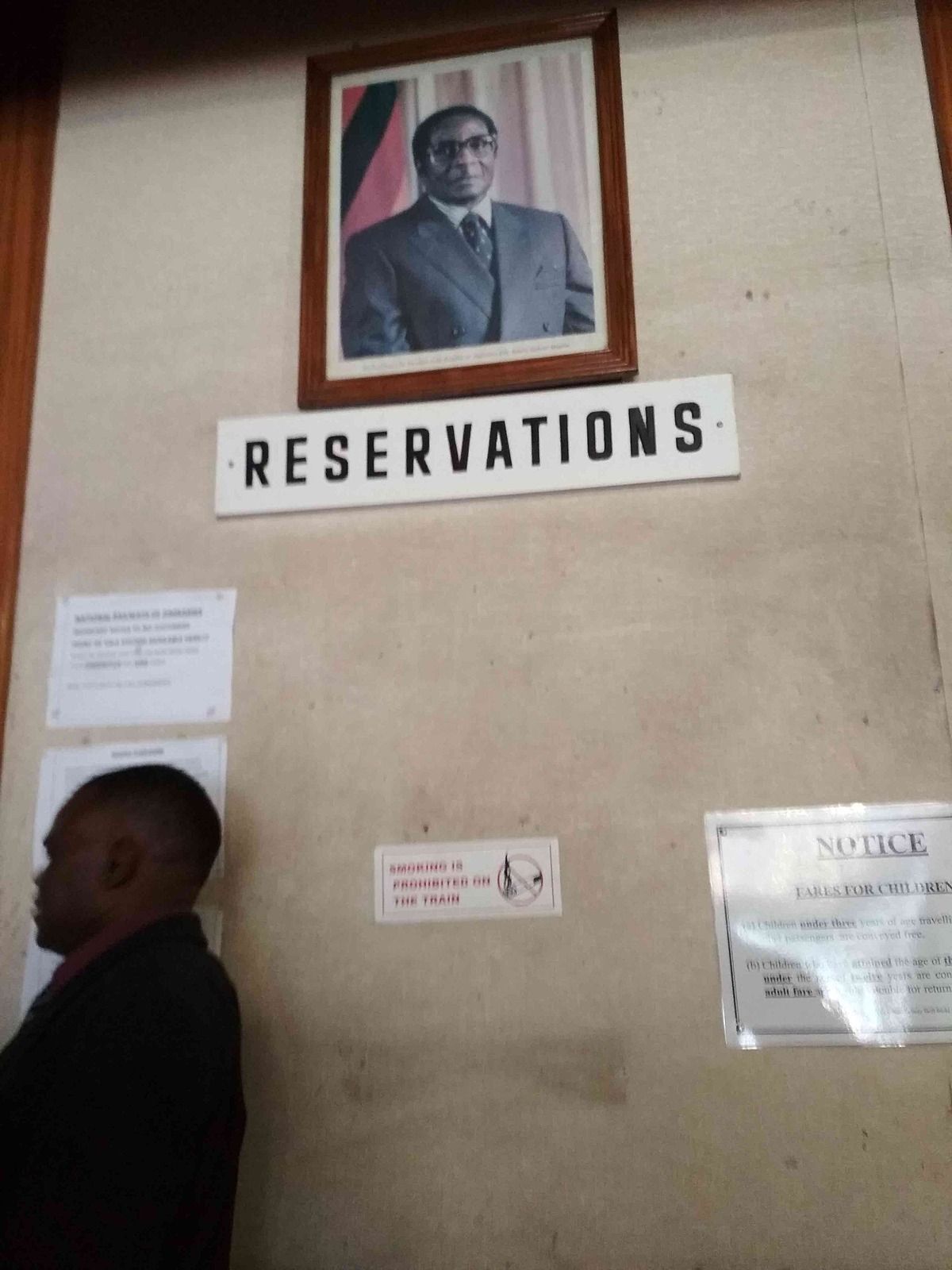

Despite the thought that Mugabe might stick around a while in the popular imagination, I was still surprised to see his portrait at the Bulawayo train station reservation counter in late December. I can imagine holding onto his portrait for a few weeks – maybe storing it next to some spare ticket chits – but who would keep it on the wall? And why?

The same courtesy to Mugabe was not shown in the Nelson Mandela Avenue location of an OK Supermarket in downtown Harare. There the President also stared down over the cashiers – but this President was not Mugabe but his successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa. These were the only presidential portraits I saw in the whole country, though I soon started finding – imaginary or otherwise – curiously blank spots on various official walls where a portrait might once have hung.

Surely, we should be pleased with the removal of all traces of Mugabe? The situation, however, felt half-finished like that feeling when a sports match ends in a draw or a TV show flashes to the credits halfway through the plot with only 'to be continued' to explain the interruption. The answer to my unease came to me courtesy of a Bulawayo hotel owner. When I asked him about the change of government, he stopped me. “The government has not changed; only Mugabe has gone. The rest are all the same.”

The government has not changed; only Mugabe has gone. The rest are all the same

So what are we left with of Mugabe's rule? He was in power for more than a third of a century but he was not on the banknotes. Zimbabwe is one of a handful of countries where the official currency is the US dollar, but in late 2016 they also issued five and two dollar 'bond' notes to match the bond coins that were used as an alternative to nickels, dimes and quarters. Perhaps it was suspicion that the bond would go the same hyperinflation route as the previous dollar that led to no heroes of Zimbabwe past (or present) being placed on the note. After all, who would want their picture associated with the frustration of worthless money?

Then there is the legacy in the everyday lives of the average Zimbabwean, but this will fade in the same way that memories of all of us fade as we pass through the world. There is also his continued presence in headlines of the all the local newspapers, trumpeted: “Mugabe Gets Huge Package”; “Anti-Mugabe Plot Details Emerge”.

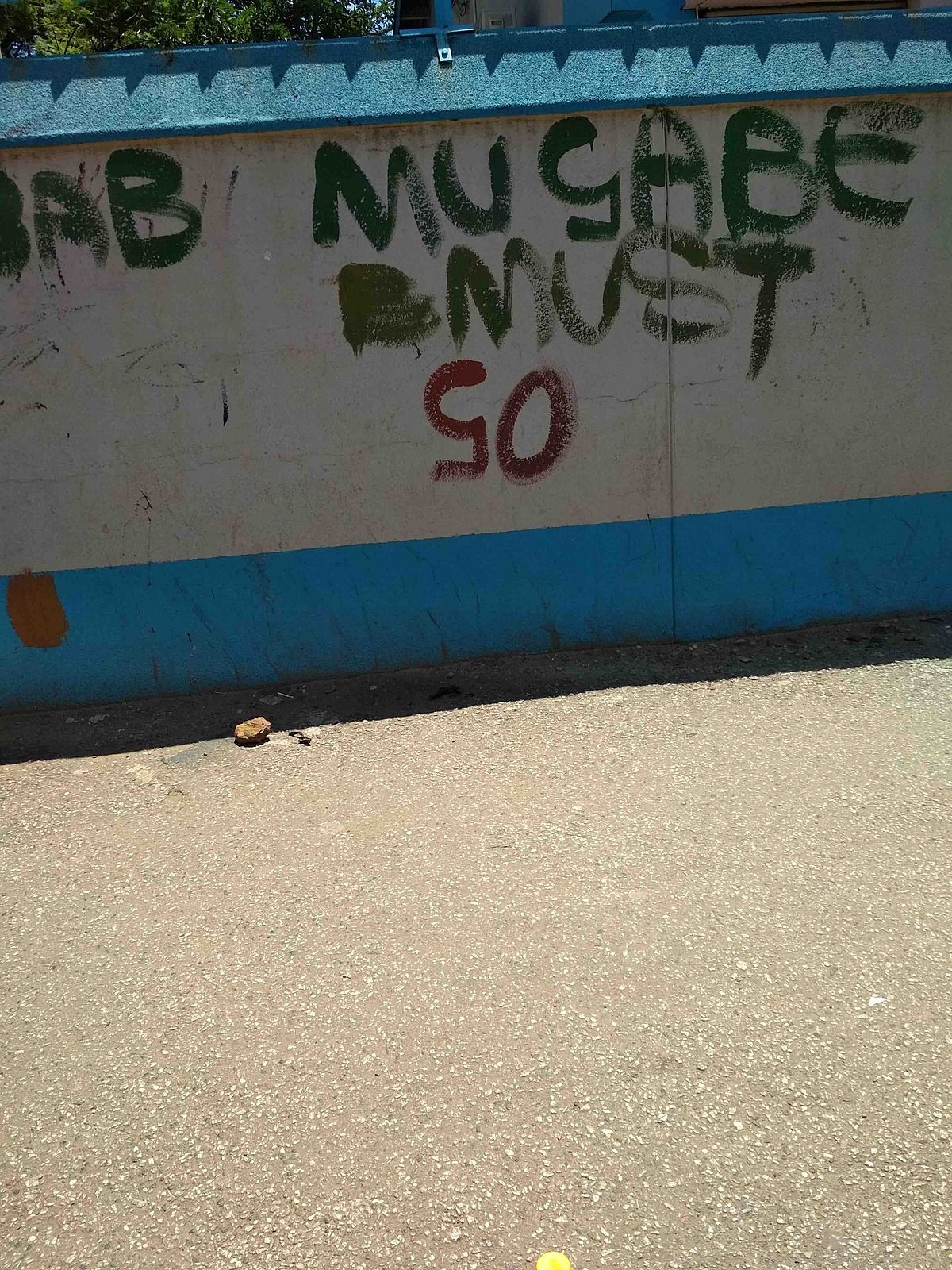

And where one might expect the toppling of a dictator to be accompanied by acres of street graffiti, all I saw was one scrawl – albeit very close to the government headquarters in Harare – which read “Mugabe Must Go”. It must have been a nervous task as not only was a letter covered over beside 'must' but an earlier attempt in the same writing had been abandoned.

The only other place where Mugabe's legacy lingered was his name on the streets: on plaques announcing the opening of places, signs directing people to Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport and the Robert Mugabe Way that run through the centre of Bulawayo and Robert Mugabe Road through Harare. While the plaques may well last, I doubt the airport will keep the name for many more months.

Strolling around Bulawayo I kept trying to find the street sign for Robert Mugabe Way. Cautious travel guides had told me to keep my flashy mobile out of sight, so without the guidance of Google Maps, I walked in the general direction of where I knew it to be. I could not find it. It was not like the streets lacked signs. While other infrastructure was crumbling, the street signs were dutifully present on every corner. But none of them indicated Robert Mugabe Way. There was one street, however, where the concrete signposts were empty; a road name having been taken down.

A pronounced public absence was the fate of Robert Mugabe Way. The same was true of Robert Mugabe Road in Harare, and also for all but one battered road sign on Robert Mugabe Avenue in Mutare.

Back in Bulawayo, I marched into a supermarket, bought another 1.5 litre bottle of water and asked a cashier what had happened to the street signs for Robert Mugabe Way.

“Ah, they've taken them down?” he asked, and seemed genuinely unaware of the change.

“That's a shame” he added as he handed me a receipt, “he's a part of our history.”

All photos are courtesy of the author.