All of Our Beginnings: Motherhood in the Exhibition ‘M/other’

Matariki Williams explores the diverse experiences of motherhood through the work of ten mother artists.

Matariki Williams explores the diverse experiences of motherhood through the work of ten mother artists.

Mother. Mum. Mom. Māmā. Responding to motherhood, it is impossible to know where to start, with this experience that is itself a start: a beginning, my beginning, your beginning, all of our beginnings. With this experience that generates so much internet traffic that a new term was coined for mothers who write about their experiences, the mommy blogger, what can my words add to the cacophony? With this experience full of newness, despite being around since the very genesis of humanity, how do I answer the question posed in the exhibition handout: ‘What do you think when you hear the word ‘mother’?’

I’ll start with my reason to visit to Whakatāne. My whānau had gathered to mark what would have been mum’s 60th birthday. We visited her in the Ohingaiti urupā she is buried in, then we visited her mum in the other Ohingaiti urupā, before driving up to Rotorua where one of my sisters was, unable to leave home due to being days away from giving birth. My time that week was, as many of my weeks are, governed by motherhood and whānau.

Waiting impatiently for our nephew’s arrival, we drove to Whakatāne for the day to see M/other. This mother did the unspeakable and forgot to pack lunch, so by the time we arrived, the kids were melting down with hunger and we were running late. Shovelling sushi into the kids, telling them not to share drinks as everyone had a cold, telling them to come back after they ran into the sunshine, waving to the exhibition’s curator Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Tūhoe) as she waited with her child in the entrance to the exhibition centre – it was a crash course in negotiation and management, a reality for parents everywhere.

Once everyone was fed, we walked into the exhibition. Some ran.

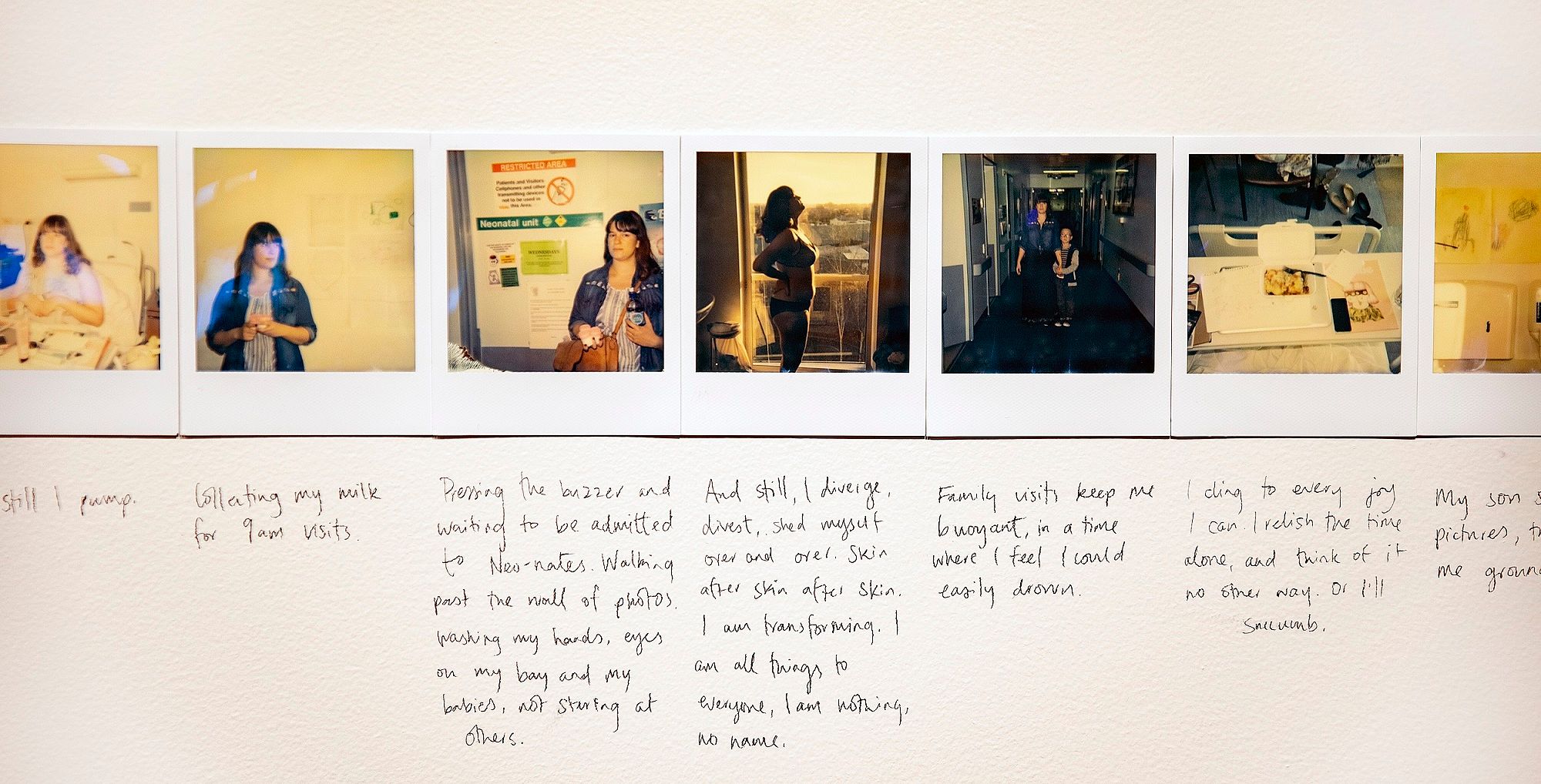

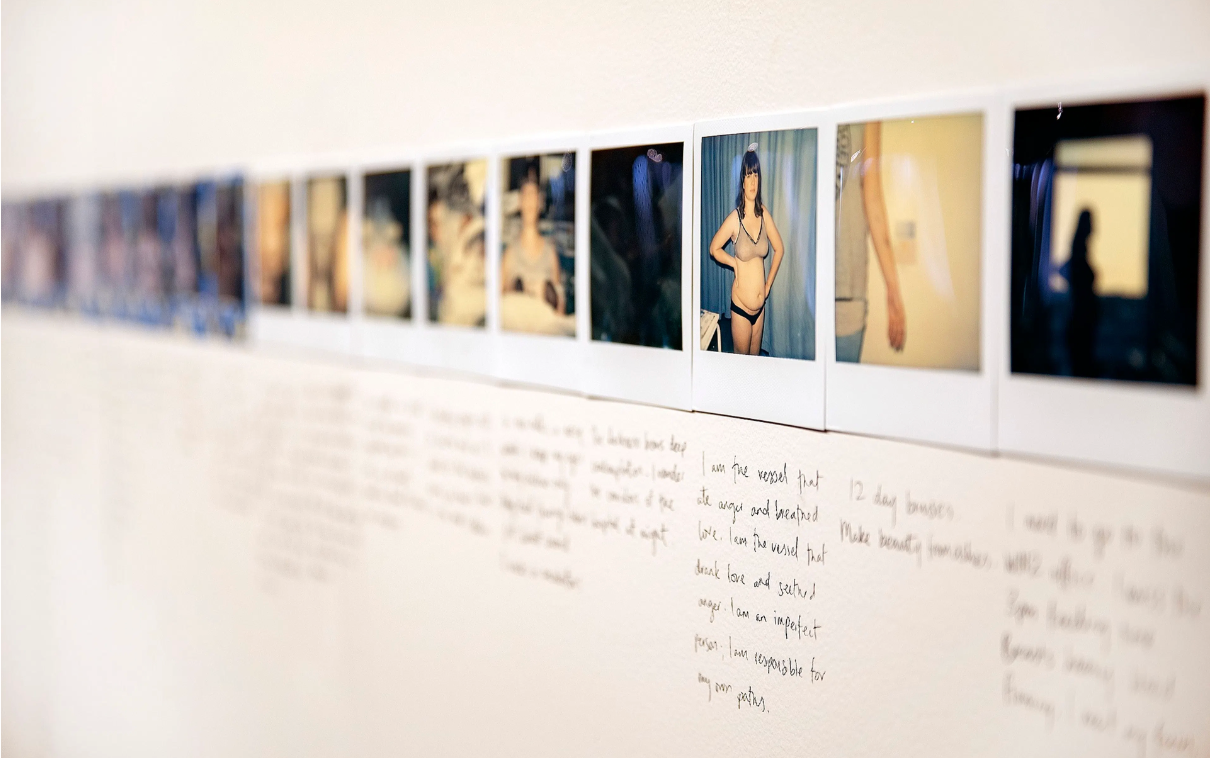

M/other features works by ten artists. Each contribution represents the wholeness of a world that I could delve into, empathise with and, this is rare, see myself in. First to capture my attention was Vessel (2016) from Leala Faleseuga. Comprised of over 100 Polaroids with accompanying hand-written text, it is a documentation of the artist’s experience of pregnancy with twins. The highly romanticised, sepia toned medium of the Polaroid is juxtaposed with Faleseuga’s raw text. This is a storied work, the artist taking with you on her journey of being a house, a home, a vessel, a mother of three, a carrier of life, including her own. Vessel is a work that begs your presence, a work that the word ‘visceral’ wishes it could encapsulate.

Vessel changes each time it is hung, with Faleseuga re-writing the text for each iteration. For this hang, one line reads: “I am a portal split open and redone.” This is where I stop and contemplate the births of my children, both by caesarean. In this line I recognise the disappointment I felt that I couldn’t have the natural birth I’d wanted, the irrational feelings of failure that my body didn’t work how it should have, the realisation that I’d never experience a vaginal delivery. Typing this I realise that motherhood is a never ending flow of judgement, and the first to judge me had been me. Reflecting on Faleseuga’s work I realise this isn’t an isolated reaction – all mothers judge themselves – but if we’re lucky, we can work through it. Yet Vessel also shows me that we can re-write our own perceptions of self, forgive ourselves for being so hard on ourselves.

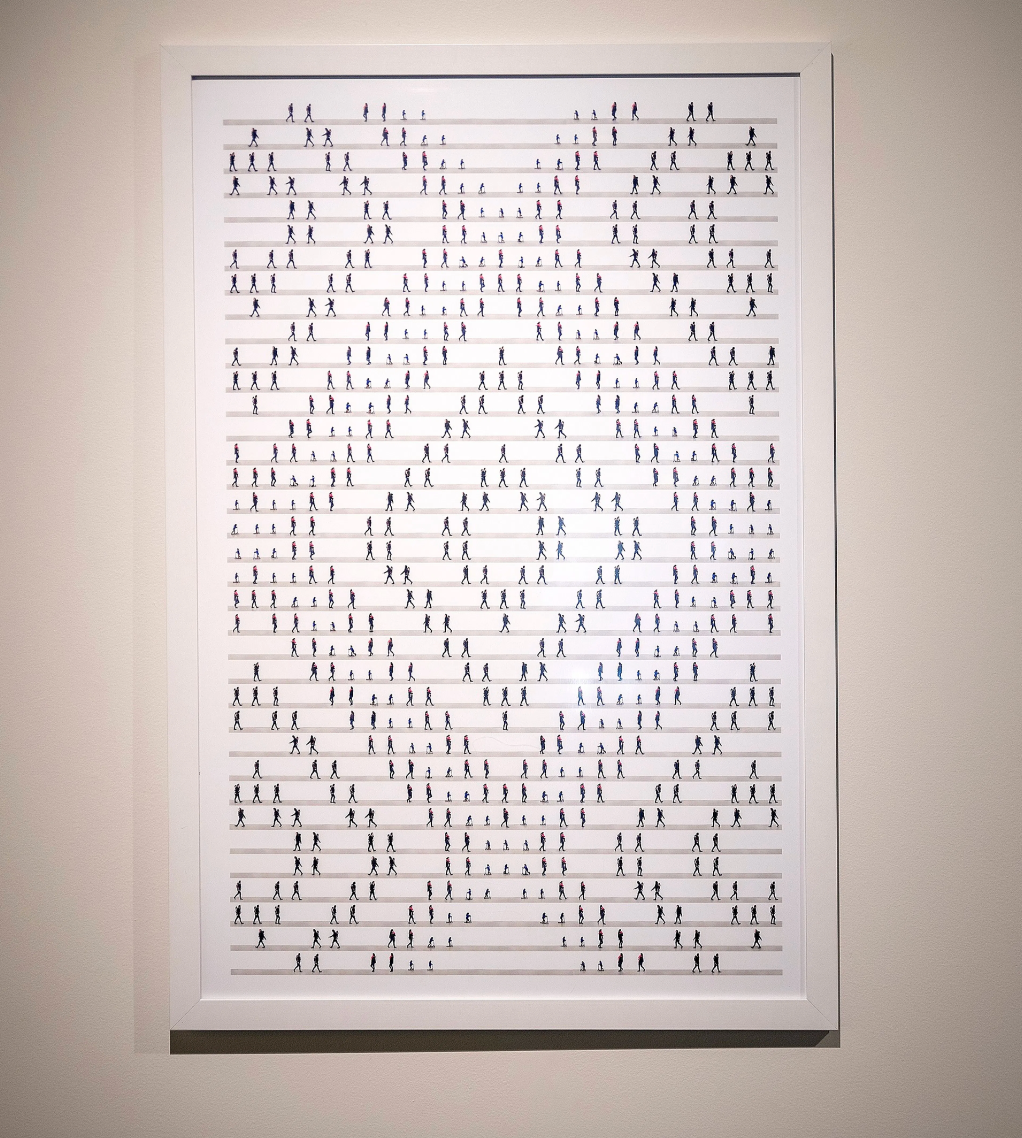

Continuing on, I see another example of the bodily labour of parenthood with Tukutuku (2019) from Erena Baker (Te Ātiawa ki Whakarongotai, Ngāti Toa Rangatira). Her work is a digital photograph depicting the relentless aspect of motherhood that is trying to get your kids to go to sleep please. The photos were taken during Baker’s recent indigenous arts residency in Banff, Canada, where her and her husband, Reweti Arapere, were both invited to participate, and subsequently took their two young children along with them. The work, though static, depicts Baker’s routine of walking her baby to sleep in the residency corridors with her toddler in tow on a scooter. It is the repetition of Tukutuku, conveying endlessness, that is so familiar, so evocative of long nights of murmuring “shhh shhh shhh” and softly swaying side-to-side. Baker’s photographs have been arranged in a pattern reflecting that of tukutuku, it acknowledges the mothers that have shared this same experience over millenia, hoping for the sweet release of sleep. Tukutuku captures that which is momentary, which will pass: you will do this again and again, and then one day your babies will be too big to for it. But your body will forever be imprinted with the feeling of their weight and warmth in your arms.

While watching Claire Harris’ video work EEG (2018), my kids’ laughter from another corner of the gallery got so loud it interrupted Sarah and I talking. Always ones for slapstick laughs, they found Justine Walker’s video work HAPPY (2016) hilarious. HAPPY is over 9 minutes long and depicts an arrangement of brightly-coloured birthday candles being lit and slowly melting, before collapsing through the polystyrene base they are erected on. HAPPY, and Walker’s other work in the show, 100’s & 1000’s (2016), deliberately employ the visually joyous objects that are synonymous with children’s birthday celebrations. Walker's works are the instance in M/other that represents an experience where the desire to become a mother was not fulfilled, a reality that is more common than many people would be aware. As the accompanying label states: “Approximately 1-in-6 couples experience infertility.” Including experiences like Walker’s in the exhibition is so important, and I thank Sarah Hudson for enabling a space for these realities to be shared.

It was perfect timing, really, to be interrupted by my kids laughing while watching EEG, a work in which Harris’s gloved hands pass an egg yolk between them, making a commentary about the inherent compromise of motherhood. Parenthood is a constant series of negotiations with yourself, your children, your partner, your family - the list goes on. I knew that I would need to talk to them later about what HAPPY is about, that I’d need to judge what they would comprehend and how to deliver the message. The juggle is real.

M/other also includes a work that speaks to the loss of a pregnancy. Whetū (2018) by Kararaina Toi is a digital illustration with text that reads: “I can only imagine you in small parts, you are never whole. How do you grieve for someone who never had the chance to exist? How do you love someone you’ve never met?” Miscarriage, though very common (Ministry of Health statistics state that as many as 1 or 2 out of every 10 pregnancies miscarry), is still not widely and openly talked about. I have not experienced miscarriage, though people close to me have, and I have mourned their loss. Whetū is pain writ on the page and I admire the artist’s willingness to share this with visitors.

In one corner of the room is the bright, inviting, playful work of Turumeke Harrington (Ngāi Tahu). Comprised of a ladder, the ubiquitous foam mat of childcare centres and a lightbulb on a long cord, Harrington’s Hey Māmā, come and play with me (2019) offers a sigh of relief to any gallery-going parent that needs a distraction for their kids so they can read the labels in peace. Except, I quickly discovered, it isn’t: “Do not climb ladder” declares the accompanying label.

Sarah explains that Harrington’s work also looks at the juggle of being a mother artist who is often in spaces that do not accommodate the behaviours of children (my own flashbacks flicker before my eyes – a kid toddling toward Shona Rapira Davies’ immense yet incredibly fragile Nga Morehu; a toddler slapping the unglazed canvas of [REDACTED]’s work). When Harrington’s work has been displayed elsewhere, visitors have been able to interact with it, and in these instances the work becomes a health and safety liability for the institution, something which Whakatāne Museum wasn’t able to manage with this show.

Gallery visits with tamariki can often be stressful: wanting to make sure that they are happy, having fun, not going to have a meltdown, and hoping that they might even learn something. As a parent, I wish this was more of a consideration for galleries, and what I see with Hey Māmā, come and play with me is the desire to take away some of this stress and make visiting a gallery a more welcoming, shared experience.

The titular work by Zoe Thompson-Moore appears alongside others she has created. With M/other, Make and make again, With Hold, What we will (2018–19), all made of cotton applique on gingham, Thompson-Moore makes a commentary on the invisible labour that is generally undertaken by mothers. This has been referred to by many as the ‘second shift’, with the related phenomenon being that of ‘emotional labour’, both of which refer to the amount of work that mothers do in the domestic sphere, whether they’re physically undertaking chores or mentally organising the calendars of every other member of the household. Thompson-Moore draws further parallels between the unpaid and underpaid labour that artists endure. Her playful, colourful, delightful textiles are reminiscent of picnic blankets and summer dresses, ultimately belying the more serious overtones of the works.

Jasmine Togo-Brisby’s whakapapa is inextricably linked to the horrors of the Pacific slave trade. As children, her great-great-grandparents were taken from Vanuatu to work on sugarcane plantations and as house servants in Australia, and her work often responds to these histories. Togo-Brisby made skulls from sugar for her work Bittersweet (2013–15), and beat the sugar bags into a tapa for Re:Finery (2016), invoking the making practices of her tīpuna. Her photographic practice places her whānau directly in the frame, where the lens has been used to exploit and deride, Togo-Brisby has taken back and used it as a tool of empowerment. With The Ships Stole Our People (2018), she is pictured alongside her mother and daughter, reflecting the strength of matrilineal ties in her whānau. Together they are powerful.

In a separate room is a video work from Tash Helasdottir-Cole (Ngāti Porou), the only piece commissioned specifically for M/other. Titled Pakiaka (2019), Helasdottir-Cole’s contribution is meditative as it slowly moves around and reveals a tree’s root system. Pakiaka considers what it means to be a mother when you’re not heterosexual, and how this influences the ways family and support networks are built. For many mothers, the building of networks can be a lifeline, providing advice and understanding. The mother on the end of the line in the middle of the night when your baby won’t stop feeding, when you’re changing the 100th nappy of the day – they are invaluable, whether they’re from the root system you were born into, or the one you chose.

Hine-Ahu-One (2014) sits right at the entrance of the exhibition and in some ways she is the beginning and end of the exhibition. By Rhonda Halliday (Ngāpuhi, Te Uri Taniwha, Ngāti Hineira, Pākehā), Hine-Ahu-One is made of burnished and smoke-fired uku and directly references the creation story wherein Tāne-mahuta formed the first woman from earth. Hine-Ahu-One renders a shape resonant of a vagina. Via its opening we can see small feet and the outline of a body. Creation stories vary but my understanding is as follows: the subsequent union between Tāne and Hine-ahu-one begat Hine-tītama; a further union then occurred between Tāne and Hine-tītama, who was so traumatised by the revelation that Tāne was her father that she fled to the underworld and became Hine-nui-te-pō. In that role, she would become the whaea for all when they pass.

In the catalogue to Whakamamae, the exhibition for which the aforementioned Nga Morehu was made, Christina Lyndon writes that the creation of Hine-ahu-one, and the following events, not only gave life to women but was also the first occurrence of the abuse of women. Halliday’s work makes me think of the wonder of life, and the accordant precariousness that comes with anything that is so precious.

It’s not often that I write about every single artist in a group exhibition, usually the column inches for a review or response necessitates omission. However, the artists included in M/other command a considered response to their works. In talking with Sarah Hudson, she conveyed that for some of the artists involved, the making of art is itself political. There’s an expectation of sacrifice when one becomes a parent, and the track record of women in heterosexual couples being the one to sacrifice their artistic vocations when they become mothers is also clear. But there are other marginalising factors for mother artists at play too: key for many parents is isolation – whether that be from a creative network or from being able to access the galleries, curators and writers that can propel careers.

One thing I always note when attending exhibitions is whether or not the works on display have been collected by institutions, and when I raised with Sarah that it appeared that none of the exhibited works were in collections (though Baker’s sold to a private collector shortly after the show opened), she knew this to be true: if women’s art is generally collected less than men’s, and commands lower price tags, am I surprised that the work of mothers is even less so?

As with anything to do with motherhood, this show could have been hung a million different ways, and looked at from innumerable angles. The reality of parenthood is that it is new every single time; even for parents with second, third, fourth children, the experience is never the same. If I were to have more kids now, my experience would be completely influenced by something I never had 6 years ago when my youngest was born: a smartphone. The sheer magnitude of how motherhood is intellectualised, commodified, vilified (fuck you to all the child/breastfeeding/mother-hating click bait), and Insta-fied online nowadays boggles my mind. The even greater offshoot to this is the ways in which diverse experiences of motherhood are shared and celebrated. M/other could live on in endless iterations, into which I’d hope that everyone could find meaning. As the final line in Vessel states, “This journey has no end.”

M/other

Whakatāne Museum and Arts

20 April 2019 – 7 August 2019

Exhibition photos: Troy Baker Photography, courtesy of Whakatāne Museum and Arts