Hooked Up to Monadic Device

Sinead Overbye gives herself over to technology, for the sake of art.

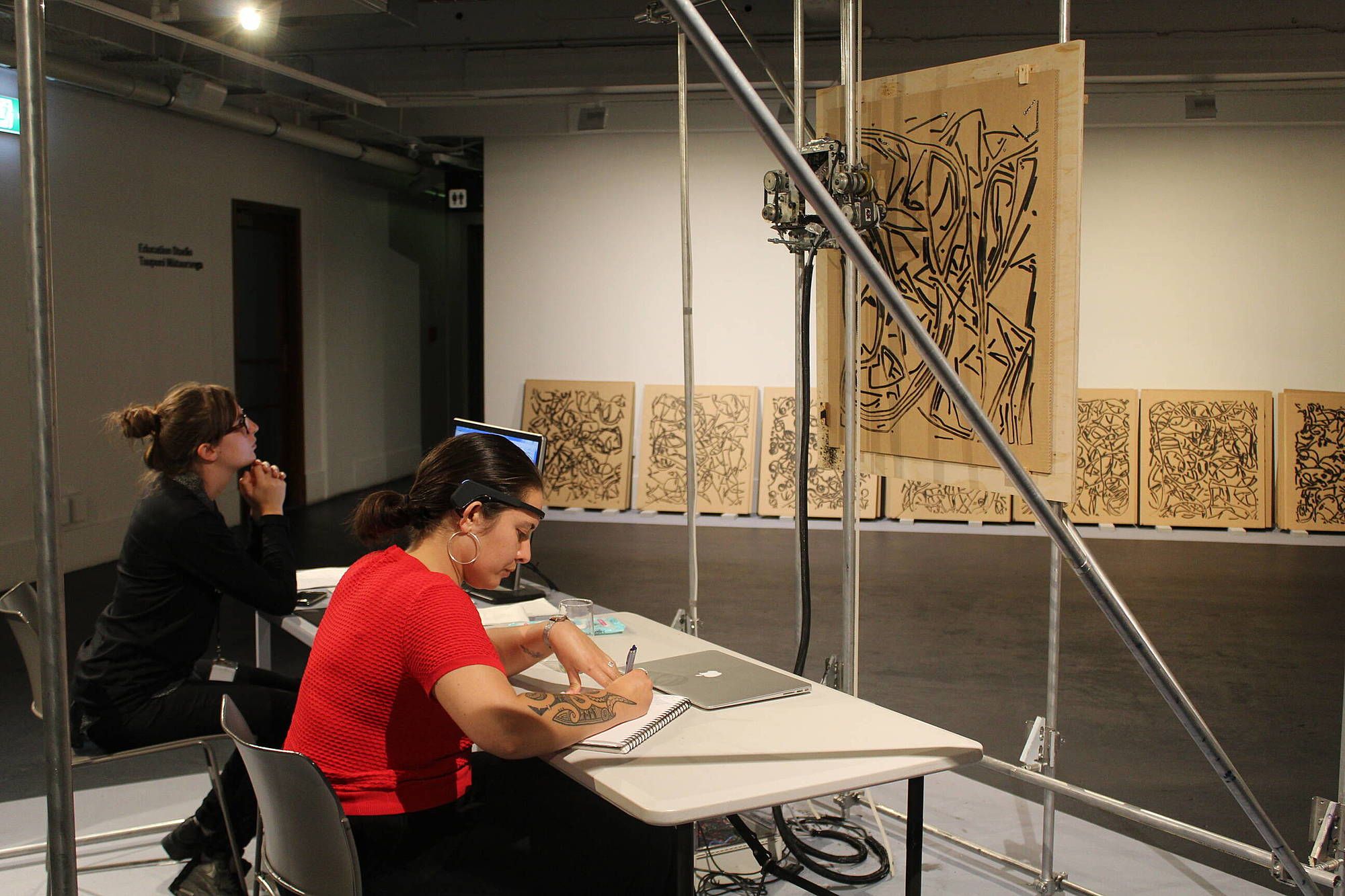

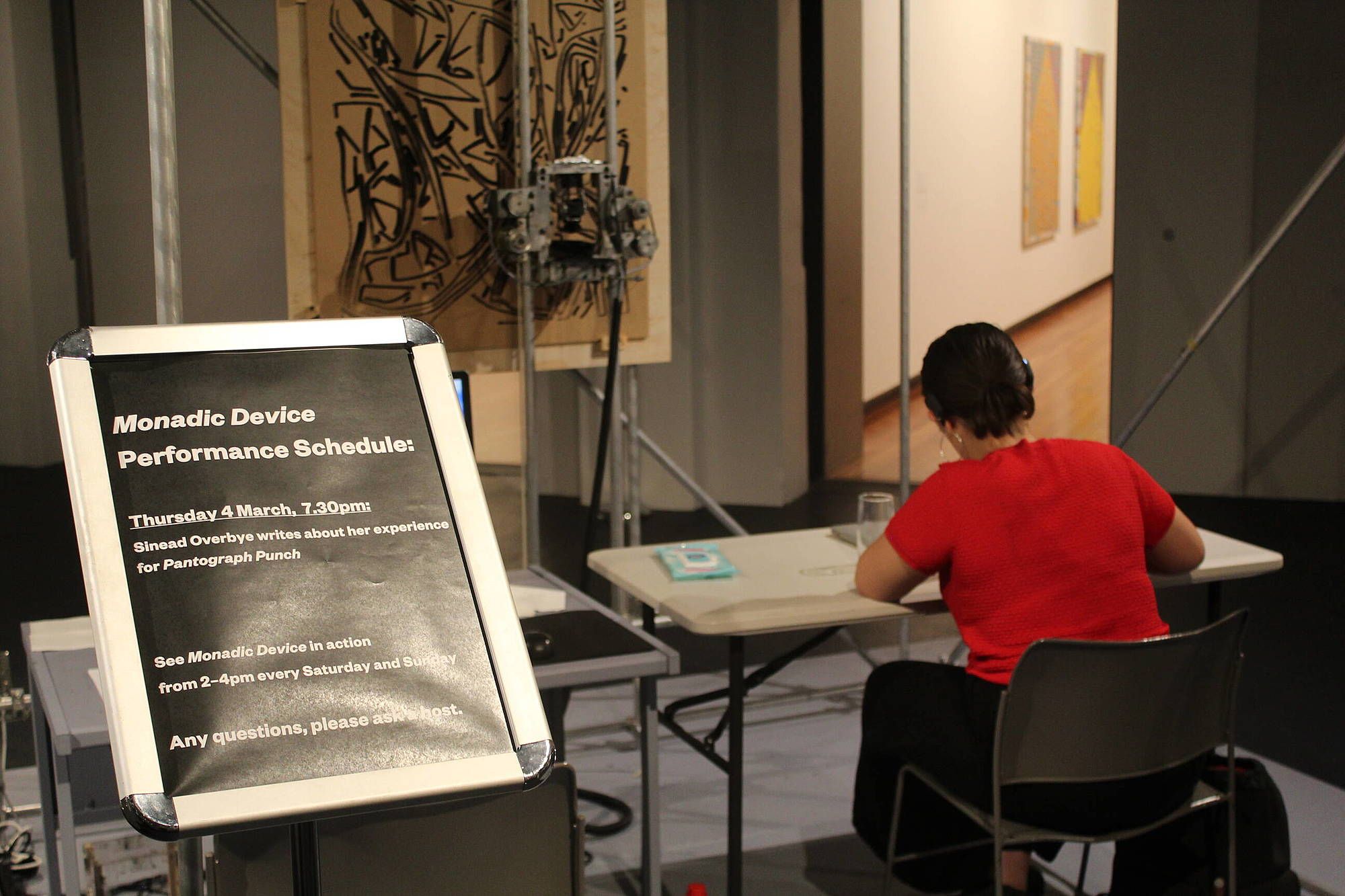

I’m sitting at a table in the middle of City Gallery Wellington with a headset around my forehead, watching as my brainwaves are transformed into a painting before me. Simon Ingram’s painting–performance work Monadic Device is designed to pick up my brainwaves from the headset. These are transmitted onto a computer screen, which is instructed to produce a set of lines corresponding with my brain’s activity. The lines from the screen are then transferred by a mechanical paintbrush onto the canvas before my eyes. Programmed so that the lines never overlap, Monadic Device collects data from my brainwaves as I sit there and perform my activity, but it doesn’t work at the speed of my thoughts – it picks up only on a few of my brainwaves, with which it creates a work of art.

It seems counterintuitive, to give myself over to technology. To allow myself to become an experiment, after all that has happened throughout history – the way art has treated Indigenous people as commodities, curiosities and objects to be documented, stolen and transported overseas. And yet here I am, being hooked to Monadic Device for art’s sake. Because it fascinates me, that this machine can record data from my brainwaves and use it to create a piece of art.

It fascinates me, that this machine can record brainwaves and use it to create a piece of art

The gallery attendant explains to me how it works, as I sit down. She places the headpiece on my head and shows me the alpha and beta waves of my brain on a phone screen, and tells me how it connects up to Monadic Device, dictating which image will be produced. I’m fascinated. I love to be told who I am. I love for people to come up and say, “This reminded me of you.” My desire to figure out my own identity leads me into strange situations, like this one, of experimenting, of testing waters to try and understand more about myself.

===

As I’m being hooked up to Monadic Device, I start to reflect on the implications of this machine, for me as a Takatāpui, Māori woman. It feels wrong for me to give some of my very own brain data to a machine, for art’s sake. It feels so invasive and ethnographic; I almost expect a colonial settler to pop out with his camera flashing unashamedly and yell, “Aha! We have captured a native Māori!”

I’m aware that I’m willingly placing myself in the position of Observed, of Other. To measure, observe and analyse Indigenous peoples was a crucial stage in colonisation, perpetuating myths about Māori, damaging our perceptions of who we were, leading to real-life consequences. It seems inappropriate for me to take up this space. But I consent to being connected to the headset anyway. I want to see myself as a work of art. I want to see if the image it creates shows me something new about myself, about who I am. I love to be told who I am, and what I’m like. I love to be seen.

===

I have this fear of technology, which is by no means unique to myself. Increasingly, I am aware of the invasiveness of the devices we carry with us every day. What bothers me is not the lack of privacy so much as the way my laptop and phone function as livestreams of my internal thoughts. My search history creates a map of the innermost workings of my brain and is therefore invasive.

We give over our data constantly

We’re acclimatised to a technological environment in which we forfeit our privacy for convenience. We give endless amounts of data to our social media apps. We Google things to figure out the answer to our random thoughts, like ‘Who played Princess Diana in The Crown?’ and ‘What actually happened to Steve from Blue’s Clues?’ We ask Siri to set timers for us while we stand at a distance. We send pictures that don’t have much significance to anyone else, just to show them: This is what I saw, this is what I’m feeling, this is who I’m spending my time with.

We give over our data constantly. Our devices absorb us and reflect us back to ourselves. And we like to see ourselves reflected. We like to manipulate the algorithm so the only thing that seems real is our own pocket of the world, a world that we believe in.

===

The experience of writing while hooked up to Monadic Device is enthralling and scary. People gather in the gallery behind me, watching as the painting appears in real time. I sit there with my notebook, writing, pretending I can’t see them. To these members of the public, I’m a performance artist, a part of the exhibition they’ve come to see.

I hear them making observations about me and asking questions as I sit there, being analysed:

“Can we know what she is thinking?”

“Can we match up each of her thoughts with each line in the painting?”

“What is she writing about?”

“Can we read what you are saying about this experience?”

“It looks as if she’s writing about art.”

“Can we have a copy?’

‘It looks as if her writing is profound.”

“Can she tell us all her thoughts?”

“Can we know what she is thinking?”

Simon Ingram: Monadic Device, City Gallery Wellington, 2021.

This is an experiment. This is a work of art. I am practicing the art of Honesty. I am showing myself to the world, in all my complex energies. It’s strangely confronting, to feel that the machine is getting to know me, the way no human ever could. It is familiarising itself with my brainwaves. Not even I know all those parts of me.

I like to hear the machine gyrating across the canvas, rotating, elevating. I like to see the strange shapes of my brainwaves come into being, like the birth of an unknown animal. It feels weird to sit here and have my brain data analysed, but it is also entrancing and beautiful. I’m not the kind of person who would do this. I’m always leaving my phone in another room, so that anyone who might be listening through it can’t hear. I’m always deleting my Twitter account, over again, to try and erase my existence from the internet. I go off the grid every other week. But technology is an addiction, and I’m leaping all the way in.

===

The more society shifts, the more frightened I am of being Māori in a world like this one. I am not afraid of my own Māori identity. Rather, I am afraid of the aggressive enthusiasm shown towards te ao Māori at the moment, from those who exist outside of it. I am afraid that there’s a spotlight being cast on Māori that allows us and our culture and our reo to be observed and remarked upon. I am afraid that this spotlight will lead to us losing control of what belongs to us.

More and more, there is a great need for us to protect ourselves, as much as there is also a desire for us to be generous and trusting, and share our knowledge with others. The way that we are being observed at the moment almost, at times, reminds me of the attitude of the first explorers. I think back to those colonial artists who painted Māori as they painted flowers – meticulously, scientifically. This tradition of measuring and categorising in order to form understandings of things has been passed down through the generations and is still being practised on Māori today. We are the curiosities of the age.

I am not just the participant in this artwork, but I am its subject

So to have this device read my brainwaves – read my mind – is strange. And to make an artwork of it – it’s so invasive. I feel anxious, tetchy, like I’m not allowed to look up at the painting. It feels vain, to stare up at it, like catching my reflection in a shop window as I walk past.

===

I always look to machines to tell me who I am. I rely on algorithms. Sometimes I worry that I’ve never had an original thought in my life, that it is not possible to have such a thing in this world where everyone seems to be thinking along the same lines – but not even freely thinking, more like they keep being given things to think about by news, by media, by technology.

We are like birds, flocking. We are making our own individual decisions to fly, coincidentally at the same time. Coincidentally, we are flocking, migrating. Coincidentally, we’re all participating in a larger system. Contributing to it. Feeding off it.

===

In my life as a research assistant, when I am coding data, I think I know what a person is saying, or who they are, but the data they give me is only the briefest glimpse of a full person. “You need to give them room for becoming,”my colleague says. “You’re coding their thoughts now, but these won’t be their thoughts forever, or in a few weeks.”

In every representation of myself, I am constantly in a state of becoming. I am constantly developing myself. Data does not define us, but it can give us a glimpse – like a brain photograph. It’s capturing a moment of my being in this world, of 1.5 hours of my brain’s activity, but it’s not showing the real me, just as my own devices don’t show the real me either.

Simon Ingram: Monadic Device, City Gallery Wellington, 2021.

I am not just the participant in this artwork, but I am its subject – and I cannot converse in a reciprocal way with the machine. The machine takes what it wants from me, as does the audience. They decide what it is and what it means. I cannot choose what to give back to them. These are only my thoughts. I become data, only data, I am data in action, I am an animal I am an artist I am a machine just writing and this is profound this is a reflection this is not just a teenage diary this is the deepest recess of a writerly brain but I am not giving up my power. This artwork is not able to be analysed by others. Its lines and patterns are complex and representative of this moment, and only I will ever know what they mean. Only I will ever read what was written during that session, so the artwork and I are connected, the painting becomes my own.

===

At the beginning of the experience, I feared the machine, that it would tell everyone what I was thinking or who I was. This felt invasive and it frightened me. It felt risky, to sit at Monadic Device and reflect on the implications of being seen in this way. I had hesitations. But the resulting artwork is deeply personal and special to me. It is indecipherable and wholly my own – as much as it belongs to Ingram, its creation was experienced by me alone and required my consensual participation.

I shut my notebook, put down my pen, stare up at the arm as it finishes carving out the last of my thoughts. And when I return to take the painting home, and hang it on my wall, I remember that moment of my life, and the time spent in the device’s presence. I think of all the observers, wanting to analyse my thoughts, and I realise how impossible that is. I am in charge of my own mind. This artwork is meaningful only to me and I think, maybe it is mine.

Monadic Device was exhibited as part of Simon Ingram’s recent exhibition The Algorithmic Impulse, at City Gallery Wellington.