The Brown Core of Mokopōpaki

Eloise Callister-Baker considers K Rd’s newest art gallery.

Eloise Callister-Baker considers K Rd’s newest art gallery.

The gentrified heart of St Kevin's Arcade has arteries spreading down the road. But many of Karangahape Road’s occupants and frequenters – the Auckland Girls’ Grammar School students, sex workers, eccentrics, small-shop owners, immigrants, artists, vagrants – are still present.

At the start of this year, fifteen participants in the Adam Art Gallery Summer Intensive walked with director, Christina Barton, down Karangahape Road to gain insights into Auckland’s contemporary art scene. The group visited Anna Miles Gallery, Michael Lett, Glovebox, Hopkinson & Mossman and met with Artspace director Misal Adnan Yildiz. Each participant wrote essays responding to an aspect of this experience.

As much as the participants seemed to enjoy the experience, they also picked up on the inherent contradictions that exist along this road. One of the participants, Nicola Caldwell, wrote that the galleries on Karangahape Road, “occupy a peculiar place in the social and economic ecology of the area. On the one hand, they are enmeshed in the history of artistic and cultural experimentation and, on the other, they operate as spaces of gentrification, lifting both rent prices and intellectual expectations.” What is happening on Karangahape Road is what has happened and is happening in similar areas around the world, like in New York City’s Chinatown and other districts, London’s Peckham and Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights.

Tea and sandwiches promote conversation, alcohol does not...

Then along came Mokopōpaki.

On 1 March, a month or so after the participants wandered down Karangahape Road, Mokopōpaki opened at 454 Karangahape Road. The new gallery both works with and against the established flow. It exists on a busy road in a city undergoing a housing crisis, but it also deliberately subverts aspects of what we have come to expect of the dealer gallery.

I met Mokopōpaki’s director, Jacob Terre, on a Wednesday evening. He wore a royal-blue cap and glasses with transparent rims and sides. He had come from an opening at Melanie Roger Gallery, which is several doors down from Mokopōpaki. Terre unlocked the gallery and invited me to take a seat underneath the gallery’s noticeboard in the salon. He then popped around the corner to the partly obscured administration area of the gallery to make tea. "Tea and sandwiches promote conversation, alcohol does not," Terre said of why he prefers to serve tea instead of alcohol, especially at openings.

Mokopōpaki also serves a personal function. Named after Terre’s grandfather, Mokopōpaki is his way of connecting to his mother's Māori family "There is some unknown information about that side and I want to discover more about this through artistic means. This enables me to do that.”

Terre (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Raukawa) is a collaborator, architect and artist. Working in Auckland dealer galleries, Michael Lett and Starkwhite, he became drawn to the less restrictive parameters of the art world over architecture. “I found things in the art world could happen a lot more quickly.” This connection to architecture deeply informs Mokopōpaki's identity which has been crafted to "reflect a Māori universe, a centre, a core".

Emma Fenton, another participant in Adam Art Gallery’s Summer Intensive, wrote of St Kevin's Arcade's sterile surface as reflecting "the interior spaces of the dealer galleries that now line Karangahape Road. Consistently fluorescent-lit and white-walled, they are blank spaces in the diverse ecology of the area." She goes on to say, “The dealer gallery’s choice to eschew diversity might begin to reflect de Certeau’s idea of ‘urbanistic’ administration and suppression, were it not for what these spaces proffer.”

Mokopōpaki has something else going on. There is no white wall in any part of the gallery.

If that speaks to the status quo, Mokopōpaki has something else going on. There is no white wall in any part of the gallery. The four main colours in the gallery are from Le Corbusier's Architectural Polychromy colour keyboards conceived in 1931 and 1959. These are “now made under license by Drikolor, a New Zealand colour technology company” and formulated by Terre’s Drikolor’s colour maker and friend Hanna Lacey. “The colour is a key part of its inception,” says Terre. “Before I came along it was white and I have removed all the white to create an anti-white space.” Its brown centre in particular disrupts paradigms of the contemporary, dealer gallery.

The brownness of the gallery’s walls; the Māori themes and stories in the art itself; the use of te reo Māori in many of the exhibited artworks’ titles and accompanying exhibition text; and how Terre works with artists to decide on the exhibition’s curation, all represent the values of the gallery. These are, at least from my existing understanding, a highlighting of Māori values which bring into consideration issues of who is and isn’t represented within dealer galleries. These values also bring to the surface both how identity can influence art making and how it can affect an artist's success.

When the gallery is open, Terre hangs a handmade flag outside; when it is closed, the flag is returned to the window display at the front of the gallery. The flag is made of strips of grey, brown, blue, black and yellow, which are colours that appear throughout the gallery. Yellow tape marks the gallery's name on the window. Past the window and first door is a small foyer. Stairs on the right lead to a flat upstairs and straight ahead through another glass door is the gallery.

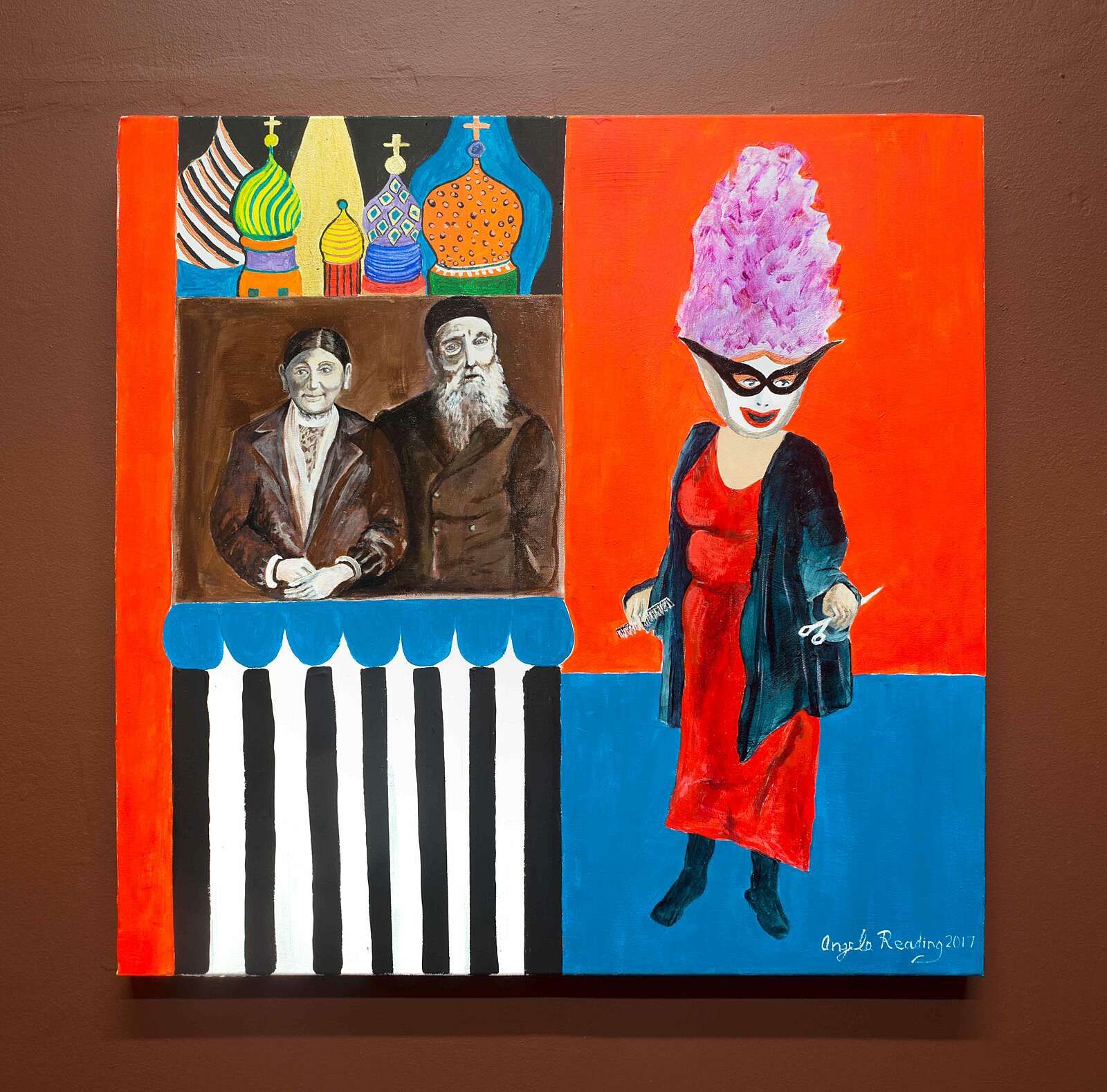

The front room is the Salon des Refusés or Exhibition of Rejects. The walls painted a light grey called gris clair 31 and the ceiling a blue called céruléen moyen. The walls are filled with a motley collection of works for sale. Works are sold and removed from the walls, new works may fill their spaces or Terre may decide to leave the spaces where they hung empty — an evolving show with no fixed timeline. The artists are all people who Terre has come to know over the years; many of them are friends. Some artists are in their twenties; others are much older. Some artists use pseudonyms; others are working within collectives.

Like the artists' themselves the works in the salon diverge in medium and concepts. Eleanor Cooper's All the places no one has ever been is a sand-cast bronze triangle and wand. Ronan Lee's works are found canvases layered with nails, staples, tape and finished with a metallic paint. Trisha McCormick's works are people made of Cadbury Rose chocolate wrappers on paper and photographs of what looks like scrubbing brushes with modern doll-faces painted on.

I want to challenge artists to consider this place where they are; I want them to think about identity ownership and the meanings of all those things in the creative production of work. I ask artists to respond to the brown condition, the brownness, the Māori centre in a way that they want to.

The terre sienne brûlée 31 brown walls of the gallery's second room beckon. While the works in this room are also for sale, the brown room is its own distinct exhibition space. As well as its brown walls, the room also has a shower (currently without the showerhead) permanently installed in its corner as per the landlord's requirements.

For exhibitions in the brown room, Terre invites artists to respond to the brownness of the space, which is a political as well as an aesthetic choice, and produce new works for it. "I want to challenge artists to consider this place where they are; I want them to think about identity ownership and the meanings of all those things in the creative production of work. I ask artists to respond to the brown condition, the brownness, the Māori centre in a way that they want to. If they’re interested in doing that, the work is born out of the space. It’s not brought in from the studio, or readymade or an old idea – it’s a new idea I’m looking for."

As to what Mokopōpaki's browness says to the dominant whiteness of the contemporary art scene in Auckland, Terre leaves this to the gallery's visitors. “It’s very clear when you walk in here that something is happening, that there is an energy in here, there’s a specific feeling. It’s certainly not a typical space and of course that’s intentional. The way that people read that and understand it is ultimately up to them."

For Terre, the gallery's browness also imbues community. "In no way is this an exclusive zone at all, it’s actually the opposite, it’s inclusive, because I want to look at how we are the same, not how we are different.” Terre has heard from visitors that it's "welcoming", like "walking into somebody’s home" and it's "personal." "It’s very clear in its direction. It has to be. It’s bold. That’s a very Māori way of being - it’s in your face." Terre has set himself up with a complicated challenge: to establish an anti-white space, but also to maintain a welcoming energy. Terre leaves conclusions about how the gallery critiques the wider art ecology up to visitors.

The concepts shaping Mokopōpaki remind me of an important conversation The Pantograph Punch's Visual Arts Editor Lana Lopesi had with indigenous curators Nigel Borell (Pirirakau, Ngai Te Rangi, Ngati Ranginui, Te Whakatohea; Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki), Ioana Gordon-Smith (Samoa; Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery) and Ema Tavola (Fiji; independent) about their hopes and frustrations within New Zealand's curatorial practice.

When Lopesi asked the curators what conditions were needed for Pākehā and/or tauiwi curators to work with indigenous artists and artists of colour for it to be a mutually beneficial relationship, Borell said it, "comes to the basis of power. Who holds the power in those conversations is inherently important for Pākehā or tauiwi curators to understand because often when you are the dominant culture or voice you are in a position of power and you don’t even realise it because it’s the norm. The dominant culture really needs to think about how power structure informs those conversations."

The gallery's Māori universe is the reference point and what artists respond to. It denormalises whiteness.

By avoiding white walls and asking artists to respond to the brownness of the space and using te reo Māori Terre creates interesting power shifts. The gallery's Māori universe is the reference point and what artists respond to. It denormalises whiteness.

Mokopōpaki too reflects what Lopesi said in the conversation about the possible need to have indigenous and other communities being the majority who show works "to make up for the fact that they are not used to seeing themselves in other places like mainstream media."

Terre's collaborations with young, older, marginalised, anonymous and enigmatic artists suggest that no matter how the underlying themes and concepts change in the gallery's subsequent exhibitions, many of the artists who show are likely to continue to be representative of groups working against on beyond the parameters of dominant culture.

Terre led me into the brown room to talk through the show, Other Perspectives. The show does many things – it reacts to the space, it also reacts to and extends on New Perspectives, Artspace's (in collaboration with Simon Denny) ambitious 2016 new artists exhibition that aimed to "distil a panoramic picture of young artistic research and production in Aotearoa". Other Perspectives, curated by Terre, is Mokopōpaki's version of this show, although Terre was careful to clarify that it was not a critique of New Perspectives.

The centre piece of the show is anonymous half sister and brother duo, Yllwbro's Flowers of the Field II. Their work is made of found objects (including a polar bear ornament that references Ursula Cramner who is another artist in the show, an antique wheel, a postcard of a wētā and a Tip Top Eskimo Pie box), blue and brown screen prints on canvases, text from the New Perspectives show and permanent marker reading 'Mokopōpaki' on a print of the late Don Binney's Kōkako, Tiritiri Matangi. These are arranged together as a towering cross. The work is a re-visit of the work Flowers of the Field that appeared in New Perspectives.

Yllwbro's text for the work in the exhibition's booklet addresses the critique of the earlier work in Francis McWhannell and Lana Lopesi's review of the Artspace show. Yllwbro argue that contrary to comments about the earlier work, the latter version of the work does come together as "a unified and articulate conceptual whole." The text also explores each element of the work in darkly humorous (the Tip Top Eskimo Pie box is described as "an iconic, indigenous ice cream treat: chocolate brown on the outside with frozen Treaty partner on the inside), personal (it references friends and the artists' own spiritual/creature identities) and intelligent.

Yllwbro do not come to their openings or reveal their identities, but their spiritual/creature identities are housed in the space. The sister is represented by a wētā that hides in a vintage, extra-large matchbox on a ledge above the shower. Her long antenna poke out of the box. “She’s in the spark box because that’s where she rubs her body together, her legs together to create the ideas that are evident in the work.” The brother is represented by a kōkako and his home is in a bird marae, painted the same grey and blues found in the gallery, which hangs in the narrow foyer of the gallery. Their mystery is not coldly elusive, but charming and thoughtful. Yllwbro seem integral to the identity of the space itself.

LHOOQ/FANIA/PĀNIA!, a "new arrangement of artists", also have work in the show. Part of the collective is away from New Zealand and they have sent the three drawings in gold pen and black tape on newspaper to the gallery from overseas, which PANIA! responded to through drawings of her own in silver and black pen and yellow tape on articles from New Zealand Listener.

PĀNIA! also collaborated with builder and cabinetmaker David Kisler to make He Waiata ō Rāwiri. This work is a found metal bucket adorned with “Rāwiri” written in yellow and grey tape standing on a stool with elongated legs in the shower of the brown room.

Mokopōpaki has created a home to intelligent and interesting collaborations and transgressions.

This culture of overlapping collaborations and conversations are the spirit of Mokopōpaki. Mokopōpaki is young. The changes to Karangahape Road are happening fast, especially as the city rail construction gets further along. But what is clear is that in the gallery’s choice of artists and its decentering of whiteness, Mokopōpaki has created a home to intelligent and interesting collaborations and transgressions. This kind of boldness is all too hard to come by. Seek it out and stop by for tea – maybe even a sandwich.

Mokopōpaki’s walls are a different colour, it uses te reo Māori, its artists are on the whole lesser known and it is privately funded, which suggests a unique freedom compared to a gallery existing on public funding. It seems like it is perfectly setup to make bold political gestures and thoughtful critical commentaries. However, Terre’s elusivity as to what political stances Mokopōpaki is taking and what it is criticising feels like missed opportunities. It is early days yet and I want to give Mokopōpaki the benefit of the doubt. I am eagerly anticipating what’s to come.

Mokopōpaki

26 April 2017 – 10 June 2017

Exhibition photographer: Arekahānara

All photographs courtesy of the artists and Mokopōpaki