Is That the Pacific Ocean, or Just My Tears? A Review of Moana Don’t Cry

An exhibition about the Pacific should centre Pacific scholarship, right? Lana Lopesi asks this question of Te Tuhi’s Moana Don’t Cry.

An exhibition about the Pacific should centre Pacific scholarship, right? Lana Lopesi asks this question of Te Tuhi’s Moana Don’t Cry.

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, the Pacific Ocean was progressively divided. European and American explorers cut up the Pacific, what was said to be the last place to meet colonisation, permanently transforming its cultural, economic and ecological landscapes. With these new borders, the notion of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa as tiny “islands in a far sea” was introduced to Pacific or Moana people, who are actually diverse and varied groups of people who speak thousands of different languages and span a 162-million-km2 ocean. These imaginary lines drawn across the Pacific Ocean confined Moana people to their tiny island spaces.

Working against this literal and mental confinement in the 1970s, Albert Wendt promoted the abandonment of colonial understandings of the Moana as divided into small island nations, instead profiling the possibilities of the vast ocean. Later, Epeli Hau’ofa reinforced this advocacy for Oceania in two seminal essays, revisiting pre-colonial ways in which the economic and social world of Moana people relied on the entire ocean. Importantly, he thought that a collective understanding of Oceania would help to free Moana people of “externally generated definitions of our past, present and future.” For all its fluidity and expansiveness, the ocean, or the Moana, has continued to be melded and utilised by Pacific scholars, artists and writers. Exhibitions like Bottled Ocean (1994) and Tangata o le Moana: The story of Pacific people in New Zealand (a long-term exhibition at Te Papa) show how the ocean has become a useful tool for new and critical constructions of selfhood.

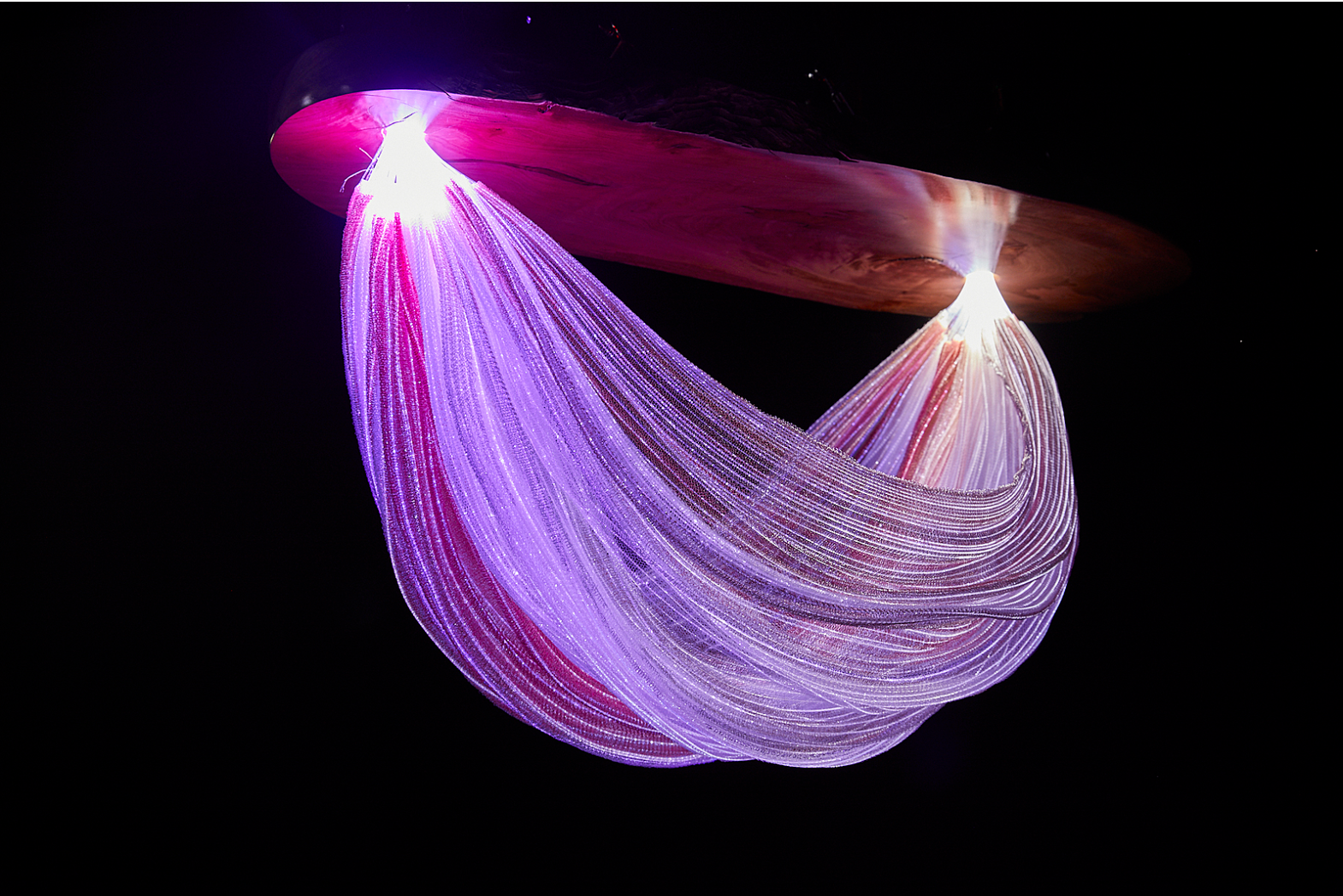

In a darkened room, the glowing sculptures are a somewhat other-worldly offering, almost god-like with their luminescent appearance. Inspired by Te Muri Beach … the pulsing light is said to reference tidal rhythms and encourage a meditative appreciation of the ocean.

More recently, this use of the ocean has become a more mainstream concept too, with films like Disney’s Moana based on an expansive ocean. Vicente Diaz critically claims that the ocean has become valorised as the essential marker of the Pacific. This too has made its way into art. Over the past two years, this conceptual framework has been used outside the Pacific and by non-Pacific people coming into the Pacific. The exhibition Oceania (2018) at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris, used these concepts as its basis. London-based critic and scholar Erika Balsom utilised the ocean to write An Oceanic Feeling: Cinema and the Sea (2018) while on residency at the Govett Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre. And most recently we see it used by curator Gabriela Salgado in Te Tuhi’s latest exhibition, Moana Don’t Cry (1 September–17 November). In Te Tuhi’s signature style of bringing together local and international artists, this exhibition features the work of Charlotte Graham (Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngāti Whanaunga, Ngāti Pāoa, Ngāti Tamaoho); Ioane Ioane (Sāmoa, Aotearoa); Knitlab (Aotearoa, Korea); Graeme Atkins (Ngāti Porou), Alex Monteith (Ireland, Aotearoa), Natalie Robertson (Ngāti Porou, Clan Donnachaidh), Kahurangiariki Smith (Te Arawa, Tainui, Takitimu, Horouta and Mataatua) and Aroha Yates-Smith (Te Arawa, Tainui and Horouta), Tuan Andrew Nguyen (Sai Gon, Viet Nam) and Francis Alÿs (Belgium).

The curatorial text tells us that the exhibition approaches “the ocean from a number of angles.” These angles include Indigenous epistemological understandings of the ocean, and climate change. As curator Salgado writes, “the exhibition addresses the need to protect life as kaitiaki (guardians) with a duty of care for the planet entrusted to us”.

Moana Don’t Cry borrows its name from Ioane Ioane’s opening-night performance of the same name. It also riffs off of Kahurangiariki Smith and Aroha Yates-Smith’s work, He Tangi Aroha – Mama Don’t Cry. So what’s all the crying about?

Walking in to Te Tuhi, the first work you see is Ioane Ioane’s Va’aalo Savaii (2019) which sits in the foyer. A Samoan fishing canoe or va’aalo made by Mulitalo Malu Tautua (Sāmoa) sits underneath a poi made out of blankets and wool which is hung from a 1000 ml IV bag of sodium chloride (the chemical name for salt), suspended from the ceiling. The contrast in materials is somewhat intriguing, if not suspicious, as if the boat out of water needs the bag of salt as a way to remember its oceanic context. Ioane writes, that the va’aalo is a metaphor for the person: “each bit of va’aalo is from nature (no nails, wires, etc.) and self-made by the carver. Therein lies the makeup of a person.” On the opening night a performance, Moana Don’t Cry (2019), involved his daughter Sila Ioane and his niece Shannon Ioane pouring water into the boat. According to the artist, the women’s bodies were metaphors for va’aalo. Ioane writes that “This existence is the moana within and of us.”

Another inclusion of fishing boats in the exhibition comes through the film Bridge / Puente (2006) by Francis Alÿs. As part of his recurring interest in borders, Alÿs organised for fishing boats in both Havana, Cuba, and the Florida Keys, USA, to gather and line up side by side in the ocean. The aim was that enough boats from each side would line up, forming a bridge between the two locations. The bridge in the film seems an earnest symbol of reconnection, to mend the separation between Cuba and the United States that has been in effect since the Cold War. The earnest gesture remains just that, however, when in Bridge / Puente the rough ocean and lack of numbers means it never quite eventuates. A cynic’s take would suggest that the failure in Bridge / Puente exemplifies the way that contemporary art gestures often stay as just that, having little implication in spaces beyond the art gallery. It is a somewhat satisfying reminder of the strength and unpredictability of our turbulent seas, in the light of contemporary art.

The sinking of islands due to rising sea levels is an incredibly imminent reality for places like Kiribati and Tokelau. The Island reminds us of the grave situation of impending climate-change refugees, while offering no solution, only an inevitable end for these populations.

At least one quarter of the carbon dioxide released by burning coal and from oil dissolves into the ocean. When this happens the pH levels drop. This is called ocean acidification, or OA, and impacts on the ability of some organism to produce and maintain their shells. Currently the ocean absorbs around 22 million tons of carbon dioxide per day. Drawing our attention to this is Charlotte Graham’s Whakawaikawa Moana / Acidic Oceans (2017-2019). Two-sided mirrors are attached to the wall and audiences are encouraged to swivel them, revealing words on both sides. The words read ao, oa (meaning ocean acidification), kai, ika, waka, awa, haka and kawakawa. On one side the words read boldly and on the other, negative space is used leaving the words to shine through. Using both sides of the mirrors – the top and bottom, above and below – mimics the way that OA is a product of what happens above sea level but impacts the bottoms of the oceans. Graham draws our consciousness to what is on the other (or perhaps the under) side.

Knitlab’s Te Muri Waters (2019), a new commission, is comprised of three ceiling-mounted sculptures made of monofilament, copper, retroreflective ribbon with fibre-optic strands, macrocarpa and pohutukawa housing. In a darkened room, the glowing sculptures are a somewhat other-worldly offering, almost god-like with their luminescent appearance. Inspired by Te Muri Beach, each of the works references a different body of water – the estuary, the bay and the reef. The pulsing light is said to reference tidal rhythms and encourage a meditative appreciation of the ocean. Amongst the ecological concerns in the other works of the exhibition, this work provides a moment’s reprieve but it also tells us that there is nothing else we can do except take some time out for a meditative breather.

The dystopian undertones of the exhibition are perhaps best exemplified in the film The Island (2017) by Tuan Andrew Nguyen. The Island combines real documentary footage and a narrative storyline of the end of world, where the last two survivors are on Pulau Bidong. Pulau Bidong (a real island) sits off the coast of Malaysia and was once one of the world’s largest refugee camps, at the time said to be the most heavily populated place on earth. The fictional version of the island where the artist’s family once stayed for years is now sinking, and the survivors have to decide what to do, shifting between hope and despair. The sinking of islands due to rising sea levels is an incredibly imminent reality for places like Kiribati and Tokelau. The Island reminds us of the grave situation of impending climate-change refugees, while offering no solution, only an inevitable end for these populations.

After seeing Moana Don’t Cry, the question that I am ultimately left with is, what does it mean for this sense of the ocean (which has become synonymous with self-empowerment for Moana people) to be used as a conceptual, curatorial framework by non-Pacific curators and academics?

The exhibition comes together in a dramatic finale, with a mega collaboration between Graeme Atkins, Alex Monteith, Natalie Robertson, Kahurangiariki Smith and Aroha Yates-Smith. The four-channel projection by Graeme Atkins, Alex Monteith and Natalie Robertson, Te rerenga o Waiorongomai ki uta, ki Waiapu ki tai—The journey of Waiorongomai inland to Waiapu at the coast (2019), highlights the mass erosion along the lower reaches of the Waiapu River that has been happening over the past century. As the work pans across coastlines and landscapes to reveal this damage, written histories of pastoralism and farming run along the bottom. The work is impressive, and has an audio composition by Rachel Shearer.

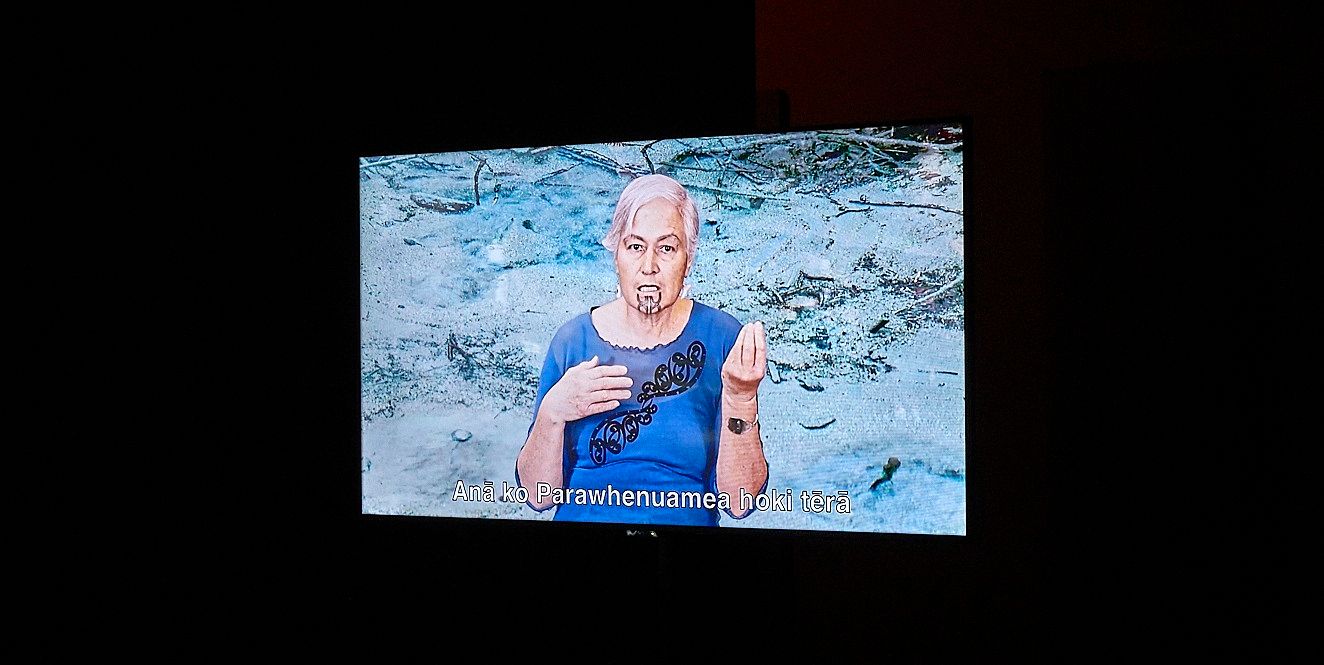

A fifth screen in the room shows He Tangi Aroha – Mama Don’t Cry (2019), by mother and daughter Aroha Yates-Smith and Kahurangiariki Smith. Riffing off karaoke aesthetics and format, Smith collaborates with her mama Yates-Smith to test whether karaoke can be a learning tool for the transmission of cultural knowledge. In this case the cultural knowledge is specifically that of Parawhenuamea, the Māori deity of alluvial waters and silt. He Tangi Aroha is at aesthetic odds with the four-channel projection, but together they also offer a unique harmony. This collaboration highlights the specificity of the ocean and its seas from different vantage points. And Smith and Yates-Smith’s work, through Parawhenuamea, washes away the damage seen on the other screens.

After seeing Moana Don’t Cry, the question that I am ultimately left with is, what does it mean for this sense of the ocean (which has become synonymous with self-empowerment for Moana people) to be used as a conceptual, curatorial framework by non-Pacific curators and academics? The cynic in me thinks that just as the Pacific was the last place to be colonised, it seems too that the Pacific is the last of the ‘exotic’ foreign cultures, ready to be used for it’s conceptual promise for arts sake.

Surely, if Indigenous ways of relating to the ocean were “paramount, to counter narratives of loss articulated by the colonial logic of dispossession”, some of those ontologies would be better represented.

The exhibition makes a nod to the “ontological turn” in which Western anthropology realises that there are other ways of knowing and being in this world. However, with the exception of Carl Mika’s words quoted on the exhibition wall (and in the essay), what is missing from the curation is scholarship from thinkers Indigenous to the Moana or the Pacific Ocean who have been writing this ontological turn into existence since the 1970s. Surely, if Indigenous ways of relating to the ocean were “paramount, to counter narratives of loss articulated by the colonial logic of dispossession”, some of those ontologies would be better represented.

Scholar Vicente Diaz criticises expansive takes of the ocean, saying that it loses the specificities of the seas within it. He writes that this has, “unleashed a tidal wave of expansive thinking through abstracted or improperly scaled or just plain tokenized ideas of Oceans…” Teresia Teaiwa writes that from the edge of the ocean “you can take what you want from the islands”, leaving what you don’t want behind, implying that those who are not in and/or of the islands get to cherry pick the parts they want, leaving everything else behind. While a number of the works in Moana Don’t Cry highlight the specific and multi-layered connection some peoples have to the water, the exhibition as a whole seems to highlight climate disasters, without doing much to mitigate them or find futures for people who call these places home. Overall, the exhibition is a detached curatorial exercise that leaves the artworks alone to do the heavy lifting. Plenty to cry about here.

Moana Don't Cry

Te Tuhi

01 September 2019 - 17 November 2019

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Te Tuhi. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Photographs: Sam Hartnett, courtesy of the artist and Te Tuhi.