Into Te Ao Mārama: A Review of ‘Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive’

Chevron Hassett reviews the potential and the future of ‘Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive’ at the Dowse Art Museum.

Chevron Hassett reviews the potential and the future in Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive at the Dowse Art Museum.

“In the beginning was Te Kore, the void. Then came Te Pō, the potential. Then Te Ao Mārama, enlightenment. Such was the creation of the world and the process of the creation of my art.” – Cliff Whiting.

To begin we must understand Te Kore, the void. It is the initial construct, before all existence, where pure nothingness resides. Te Kore, like the moments before we were conceived, a space waiting to be filled. As you become aware of what is and what isn’t, so emerges a sense of potential. Potential – this great and vast space to navigate through, to migrate from. It is the foundation for an environment to develop within.

From an understanding of what the potential is, the void that encompasses and restricts changes. The confining walls become boundless, opening a pathway transcending from one point to another, into the realm known as Te Pō.

I cannot describe how vital this realm is to all that we see, to all that we feel, to all that exists within our world. The surface of the realm is woven together with many ropes of tapu, holding and binding an environment to manaaki all that stand within it, allowing all who are shadowed underneath these ropes to become tapu. This is an environment in which we whakapapa to everything around us. There is no ‘you’ or ‘I’ without Te Pō. It is where all growth is produced, creative development is rooted within the whenua of Te Pō; it is the soil for seeds planted out of Te Kore to flourish.

This is where I see the mauri of Māori moving image practices being, sheltered in this nurturing space. Coming out from a hunger within Te Kore and into the many stages of Te Pō.

The Dowse has always felt distant or out of reach to me, though not so much in a physical sense, as it was only a 130 bus-ride away from Naenae. I could easily place my hands amongst the walls and see its artworks in the gallery lights. But it was the imperative essence, which dwells deep within the spirit, that was unable to connect and feel something more than what existed upon the surface. I was a local boy who felt foreign within the gallery walls, the works spoke in languages unfamiliar to the ear and I tried to engage. But everything seemed to be over my head and the works I saw seemed unusual or out of place.

Recently, a calling to reconnect with The Dowse Museum came. Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive curated by Melanie Oliver and Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi) called outwards, I could not ignore it any more. The need to go was heavy on me, a feeling of importance. I had to go, I had to be there.

The first step I took inside, it hit me. Without warning this blanket of warmth covered me, a flutter of life lit up inside and the presence of the artworks – scaling the walls and encompassing the gallery space – spoke. There was power filling the room, it was like a wave, flowing, swimming to greet you. It was at my feet and pulling me towards it. Each step into the gallery this presence grew and grew, asserting its place and providing a reminder of where I stand. Where we stand.

Of course, the fabulous mana wahine Lisa Reihana (Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngāi Tū) stole my attention with her revolutionary waharoa work from 1997. Called Native Portraits n.19897, it is difficult to explain the emotion it made me feel. I was only three years old when this work was made, it’s crazy to fathom I was still in a car seat while Reihana, as a young woman, was shaping a moment in time, a moment that would stand for decades. Native Portraits n.19897 is an eleven-channel work resembling the traditional carved waharoa, gateway, with intricately carved figures who guard the entrance on many marae around the motu. Reihana acknowledges the lineage of carving but directs herself forward, to the future, extending the recognised understanding of a waharoa into a more familiar form for the contemporary position of our people today. Reihana streams a rich understanding of her whakapapa and, combined with mastery of her camera technique, a waharoa appears.

A myriad of people are composed together in sequence throughout the piece. Some are adorned with kākahu while others are in piupiu, colonial attire and workmen’s outfits. They transport the viewer back and forth, flicking between an era of before, an era in-between and an era of today. With grace and skill, a poi rotates in and out around the work. There are quiet moments where resting portraits pervade the screens, offering a time to reflect, then with a sharp, swift interruption toa conquer the screen, challenging the viewer, laying out a wero. Before we enter through the waharoa another interruption occurs, wāhine humourlessly halt the space by directing the viewer with the use of a road-worker’s stop-and-go sign. An admirable aspect of the work is Reihana’s ability to bravely and seamlessly intertwine captivating portraits of whānau and friends. With her kaupapa firmly in their hearts they perform with courage and aroha, each person then doing a mihi to the camera. Allowing themselves to be vulnerable to an unknown audience, they guard themselves with finesse, their mana moulds together and collectively everyone stands tall. Subtle in the process but bold in statement, this inclusion of whānau and friends reinforces the values of whanaungatanga from everyday life into the white-walled gallery space, building forth a foundation to scaffold upon the collective representation of her people. As my granddad would say, “That’s the wanawana.”

As my granddad would say, “That’s the wanawana.”

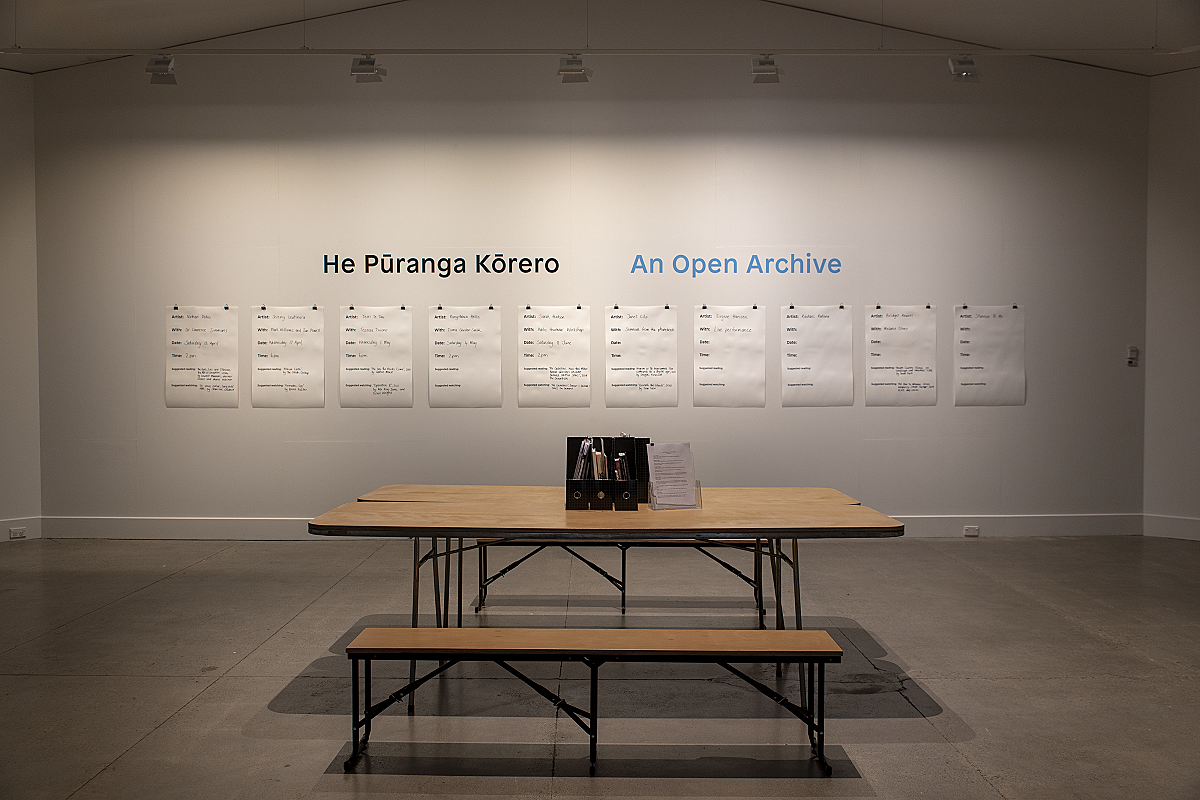

In front of Native Portraits n.19897 is an open space that extends into three other attached rooms. Centred between the three is a room that invites visitors to wānanga, it is a sheltering space for learning and encouraging enlightenment. It is not something you commonly see within an exhibition, so the decision to include such a space and particularly to recognise its need excites me. Arranged in this space is an archive of resources, books and papers, with red tabs poking out of the books signalling out key information that has influenced each artist’s practice. I recognise a few classics that most Māori artists should know and the sense of connection and familiarity is soothing, confirming the feeling of belonging for me. Other books and articles that I had not seen are included on the table – this is refreshing as it feeds new understandings to the audience and provides further access to the kaupapa, succinctly embodying the intentions of the wānanga.

Despite this, probably the most enlightening moment in the room was when I stepped back to assess the space. It hit me that there was huge desire for more. The overwhelming presence was that of Te Kore: the archive shared on the tables illustrated that there was limited coverage of these exhibiting artists’ practices, or even ngā toi Māori more broadly.

Over coffee, co-curator Reweti expressed to me that “No one is writing about us.” To be honest, if you’d asked me four years ago, when I was studying at Massey University, to name any of these artists, I couldn’t. If you were to ask me if I knew what Māori moving-image practices were, I wouldn’t have been able to say. This is particularly startling because I am Māori, I work with moving image, and not once was I taught about any of the works or artists who are in Māori Moving Image. Yet, their work is so empowering. Each artwork is bilingual insomuch as every thought, detail and skill has been considered. Each artist exhibited can speak to Māori worldviews and to Pākehā worldviews, which not many people can do. Their ability to fluently communicate contemporary Māori existences and narratives through layers of these conventions, creative excellence and uncharted waters is inspiring.

One such work is from 2015, Te Āhua o te Hau ki te Papaioea by Terri Te Tau (Rangitāne, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa). A shifty van, all blacked out, sits silently in an open space in the gallery. Its sliding doors are wide open, encouraging visitors to enter and be engulfed inside the work. The van conveys a sensation, transporting you back to memories of riding in the car as a child, looking out the window as the clouds go by. This great sense of familiarity catches you into a place of nostalgia. Dashboard camera footage projects onto the front windows, lamp-posts and trees go past as the movement of the video drives forward through an urban streetscape. Te Tau takes you on a journey as the van traces a route through the streets of Palmerston North, where four houses were under surveillance during the infamous Operation 8 police surveillance campaign in 2007. The video’s essence of familiarity juxtaposed with the histories attached to the piece make something so far away feel so close. Questioning common perceptions around surveillance, the work presents the point of view of an investigator, an oppressor, viewing the streets through their eyes and subverting the usual position of the subject to the observer.

‘The hau, mana and mauri of the landscape and its occupants offer an alternative to conventional visual surveillance.’ – Terri Te Tau

On my third visit to the exhibition I took some keen rangatahi from the nearby suburb of Taita. For some it was their first time in The Dowse, and others had not been in years. For a number of reasons, it isn’t always accessible for many youth in these areas to visit the gallery, and when they do visit it can be quite a daunting environment. Abstract concepts, academic conversations and clinical perceptions can create barriers to a visitor’s experience. Once the rangatahi entered, everyone’s face lit up and they instantly ditched me to explore the gallery with their friends. A chuckle of laughter echoed out of the van as two of the young girls interacted with the work and, of course, took selfies. A remarkable conversation occured as to how they felt about Te Āhua o te Hau ki te Papaioea. One of the girls said, “It was a beautiful idea of a van” and I asked her if she liked the piece. She responded, “Yes, ‘cause it has a good explanation why they shouldn’t invade people’s privacy.” She was able to connect, but further than that, it challenged her thoughts and changed her understanding of what art could be and how it can communicate.

The curation of the exhibition presents a sense of freedom where opportunities to engage with the works are self-determined, enticing visitors to project personal insights into the body of Māori moving image practitioners and their histories. In the two rooms next to the archive, more recent works are projected onto the walls by a monthly rotation of artists. These change-outs allow the space to constantly evolve and intrigue, each frame offering a broad representation of unique perspectives and creative directions, laying out an endless pathway for responses to the works. In one room is the rotating cohort of Jeremy Leatinu’u, Ana Iti, Sarah Hudson and Leilani Kake, while the other room hosts Jamie Berry, Pikihuia Haenga and Leala Faleseuga (7558 Collective), Natalie Robertson, and Ngahina Hohaia.

Top left:

Rachael Rakena, … as an individual and not under the name of Ngāi Tahu. 2001.

Bottom right:

Nathan Pohio, Sleeper, 1999.

And so, the wāhine reappear with their signs, calling me to enter through the waharoa, which is still standing, holding a transient presence that enables voyage between two environments. Through the waharoa, I am directed into a capsule of works from the 80s, 90s and early 2000s. Rachael Rakena’s (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāpuhi) 2001 work … as an individual and not under the name of Ngāi Tahu orchestrates a river of magnificence and beauty over the end wall; peaceful dreamtime emanates from Nathan Pohio’s (Kāti Mamoe, Ngāi Tahu, Waitaha) 1999 piece Sleeper; and Nova Paul’s (Ngāpuhi) 2006 work, Pink and White Terraces, presents visuals enriched with vibrant colours. Together these works expand layers of conversations that weave past histories and contemporary Māori lifestyles. Though it is Dr Robert Jahnke’s (Ngāi Taharoa, Te Whānau a Iritekura, Te Whānau a Rakairoa o Ngāti Porou) animation work from 1980, Te Utu. The Battle of the Gods that unexpectedly struck me. Unaware of Jahnke’s early years, I was impressed: Te Utu was nothing like the other works of this time and it is remarkable to experience his creative genius so intertwined within the fabric of his early artworks. Jahnke’s work is interested in the spiritual importance of ātua and their āhua; it transforms the carved figure into a moving form. Te Utu has rarely been seen before, yet here were these ātua: alive, ecstatic, moving and interacting within the screen. Jahnke made you feel their existence. The accompanying soundtrack encapsulates the experience of an earlier time period: entrenched in the work, it is transcendent.

Another of the rangatahi expressed that she liked Jahnke’s work “Because I like to learn about Māori work and history. This piece shows Gods fighting and changing.” She also recognised the skill of the piece: “He [Jahnke] had put so much hard work into it and it shows much detail in what he did.” Her reaction illustrates how the work gave her a sense of pride: pride in seeing her culture represented within the gallery and allowing her to feel empowered by what was around her. That is mana.

Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive is an exhibition that is dynamic in its creative conventions and poetic in the expressive visual language it conveys. Within, it portrays artistic excellence alongside ground-breaking artworks and a love for whānau. Community deserves to be highlighted here because it is so present within the curation and especially within the artists’ works: that value, that respect, that awareness to think larger than yourself is vital and it can be lost at times, but Oliver and Reweti’s emphasis on people elevates the show to another level.

We were in Te Pō, underneath a night of potential. The garden was readied to nurture the growth of the practice. It is perfect timing, during Matariki, as we acknowledge those who have gone before, who began the planting for our years to come, sprouting into the light, that Māori Moving Image springs forth into Te Ao Mārama.

Featuring Ana Iti, Eugene Hansen, Jamie Berry/ Leala Faleseuga/ Pikihuia Haenga (7558 Collective), Janet Lilo, Jasmine Te Hira, Jeremy Leatinu'u, Layne Waerea, Leilani Kake, Lisa Reihana, Natalie Robertson, Nathan Pohio, Nova Paul, Ngahina Hohaia, Rachael Rakena, Rangituhia Hollis, Robert Jahnke, Sarah Hudson and Terri Te Tau.

Curated by Bridget Reweti and Melanie Oliver.

30 Mar – 21 Jul 2019

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with The Dowse Art Museum, which covers the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

All images courtesy of the artists and The Dowse Art Museum.