Migration, Opportunity and Betrayal - A Personal Retrospective

On some social issues, the distinctions between political parties is clear-cut. But when it comes to migration, Pasan Jayasinghe and Sahanika Ratanyake argue, progressive voters face a near-impossible choice, and some will feel a sense of betrayal.

There is a deeply entrenched tendency in New Zealand political discourse, both amongst those who make policy and those who comment on it, to discuss policies from a neutral standpoint. It’s as if they were observing an experiment, like they weren’t themselves individuals who have been and continue to be affected by the introduction of particular policies. Personal perspectives, such as that of Metiria Turei recently, are notable for their striking rarity.

So we offer the following, on immigration policy, as a counterpoint to the sort of analysis that puts aside the impact of politics on the lives of individuals and consequently presents voting as a simple calculation – a mere tabulation of the pros and cons of policies and the savviness with which they’re presented and deployed, rather than a decision informed by one’s values and life history.

The recent history of immigration policy in New Zealand (particularly policy spearheaded by the Labour Party during its time in government) and the trajectory of our lives are inextricably bound together. Consequently, we have watched the recent debate on immigration, driven by Labour, with disappointment and sadness, not just as immigrants but as voters that both identify as progressive.

Our parents moved to New Zealand during the immigration boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The boom was a direct result of the Immigration Act 1987, passed by the fourth Labour government, which ended preferential treatment for migrants from Britain, Europe and Northern America. It initiated instead an immigration system which assessed immigrants according to their potential contribution to New Zealand’s economy and society.

The 1987 Act was buttressed by the ensuing National government’s introduction of a point-based immigration system in 1991, which ranked the qualities sought in migrants and gave them a priority based on the assigned points. This opened the gate for increased immigration from other parts of the globe, particularly from Asia. Much of the migration during the boom consisted of skilled workers required to fill job shortages in New Zealand. This is in line with our personal histories: both our fathers are civil engineers. Having worked various short-term contracts in the Middle East while we were infants, they were looking for a more permanent place to settle as their children grew older.

These policy reforms resulted in massive social changes within a very short period of time. In just the early 1990s for instance, the numbers of those given approval for residency rose rapidly from 26,000 in 1992, to over 50,000 in 1995. By 2001, a fifth of New Zealand’s population was overseas-born. More importantly, immigrant flows that had largely been homogenous until the late 1980s suddenly became far more diversified.

What we recall of our childhoods reflects the diversity that the origin-neutral immigration system brought about. Sahanika’s childhood best friends in Melville, Hamilton were Chinese, Iraqi and Pākehā, a fact that did not strike any of them as even remotely odd (all three of them were far too busy trying to read all the Baby-Sitters Club books). Across town in Hillcrest, Pasan was just one of many brown candidates competing to play Scary Spice in frenzied re-enactments of Spice Girls videos.

We do not wish to paint a rosy picture of the success of multiculturalism in New Zealand. Whilst we grew up relatively unscathed, our parents faced discrimination and micro-aggressions in various forms. Like most skilled migrants, they found it difficult initially to find the work they were trained for, as they were often overlooked in favour of local employees or immigrants from European backgrounds. Nor did we all acclimate easily to our new home, as the mythology surrounding diversity suggests; the disapproval on her mother’s face when Sahanika bought her Pākehā boyfriend home for the first time suggested otherwise.

Nor do we wish to claim that the motivation for the New Zealand immigration system was altruism or a desire to foster multiculturalism. Rather, the system used and continues to use migrants as human capital for economic advancement. Indeed, the bipartisan consensus on immigration from the late 1980s to the early 2000s positioned New Zealand as a player in a “race” to secure skilled and talented human resources in a competitive global environment.

Under this framework, immigrants are essentially treated as economic units and their worth determined almost purely by the economic value they can contribute. In spite of being such units, however, it is difficult for us to discount the impact the immigration system, and the wider reality of growing up in New Zealand, has had on us.

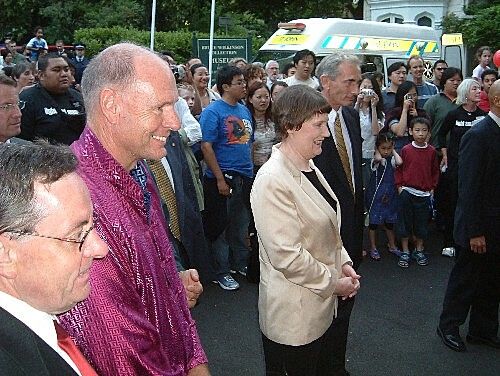

It is the local Labour MPs that we recall being awkwardly yet persistently present at each Sri Lankan New Year’s celebration, dance troupe performance, and cultural food fair we were reluctantly dragged to.

Whilst the scaffolding for the immigration boom was a bipartisan effort, it is Labour that we – and we suspect many other migrants who arrived during the immigration boom – associate with the burgeoning diversity of New Zealand. This may have been due to the timing of our arrivals, coinciding as they did with the onset of the fifth Labour government. It may also have been due to Labour embracing multiculturalism more readily and consistently, which continued to be the case even as National turned away from it in the mid-2000s (under Don Brash’s leadership in particular, the party began echoing the ‘flood of immigrants’ rhetoric so doggedly issued by Winston Peters).

This support was material: from 2003 onwards, the Labour government set up the Office of Ethnic Affairs; developed a Settlement Strategy for new migrants which resulted in a number of Migrant Resource Centres nationwide; and established the Language Line to offer telephone interpretation assistance to speakers of numerous other languages to access important government services. Labour’s only major concession to higher barriers of entry during this time was increasing the English language requirement for migrants.

But Labour’s commitment also went beyond this. It is the local Labour MPs that we recall being awkwardly yet persistently present at each Sri Lankan New Year’s celebration, dance troupe performance, and cultural food fair we were reluctantly dragged to (even though baiting them with “kiwi hot” curries which were actually decidedly spicy was a favourite pastime of Pasan). This was a time when the presence of the entire political spectrum at various cultural events wasn’t so ubiquitous, and an MP’s attendance suggested a real concern and effort.

Our parents diligently voted Labour, with a particular enthusiasm for Helen Clark they otherwise reserved only for the Sri Lankan politicians from their youth. Even if multiculturalism was attractive wrapping paper for the cold economics of immigration policy, we still find it hard to deny its emotional resonance. There was something in the bare fact of recognition, by the state and its representatives themselves, which we sensed was a comfort and reassurance to our parents, who had already navigated numerous tumultuous migrations.

We do not wish to venerate Labour’s policies and politics of race relations overall, or suggest that its relatively permissive multiculturalism absolves itself of its racist policies and actions during this period. The fifth Labour government’s passage of the Foreshore and Seabed Act in 2004 and its orchestration of the Urewera raids in 2007 stand out as just two examples of the party’s reactionary streak. Such interventions complicate the politics of a party very much in conflict with itself over how to engage with New Zealand’s non-Pākehā peoples.

This would be proved once again with the debate on immigration that the party has opened up recently; with it, Labour strayed very far from the original picture we held of the party as an inclusive one in support of diversity and immigration. In June this year, Labour announced a raft of policies to reduce annual net migration by 20,000-30,000 through a combination of limiting student visas for “low value” courses of study; removing work visas without a job offer for applicants graduating with less than a Bachelor-level degree; regionalising the occupation list and implementing a “Kiwis first” hiring policy for employers. These policies have been justified by the party on the basis that record numbers of migrant arrivals are contributing to the country’s housing crisis, putting pressure on hospitals and schools, and increasing road congestion.

The reasoning behind such policies crumbles upon any close scrutiny. The record annual net migration figure of 70,000 the party frequently cites actually comprises some 37,000 New Zealanders returning home from time spent living overseas, and staying put; 21,000 on working holiday visas; 7,000 international student arrivals and 3,000 Australians moving here. In effect, Labour’s policies are aimed at the remaining 10-15,000 migrants at the margins of current net migration. It is difficult to believe that such a number is the main cause of the country’s housing crisis, health and education pressures and congestion, particularly given that most new migrants, and especially migrant students, are not in a position to afford either houses or cars.

If the issue was simply faulty logic or ineffective policies, it would be politics as usual. However, Labour’s immigration policies and accompanying discourse slid into a dangerous form of scapegoating and xenophobia, all the more shocking given the source. Following the blatant race profiling of the Chinese-sounding last names debacle in 2015, the party has been at pains to emphasise that its policies “aren’t about race” and are in fact “race neutral”.

Notably, (Labour) has never made reference to Canadian, American, Australian or European property investors and land purchasers, who account for a majority of foreign direct investment and land acquisition in the country.

This is, however, at odds with the party’s constant references (at least under the previous leadership) to property investors from China, Chinese home buyers, and Chinese and Indian restaurants. Notably, the party has never made reference to Canadian, American, Australian or European property investors and land purchasers, who account for a majority of foreign direct investment and land acquisition in the country.

Apart from pointing fingers at immigrants from particular locales, Labour’s constant use of phrasing such as “low-skilled people” and students of “low-level education courses” paints a picture of nefarious migrants who use work and study visas as ‘backdoor’ paths to residency and citizenship. This implies that there are legitimate reasons to leave one’s country, and that reasons of economic and social advancement are not amongst them. The inconsistency between the reactionary immigration policy and relatively progressive refugee quota that the party (amongst a number of others) has committed to could be viewed as further evidence of this; it implies that it is only permissible to settle elsewhere if one is forced to, not voluntarily for mere reasons of personal gain.

Our parents are prime examples of the ‘bad’ kind of migrant under this construct: recently, when Sahanika asked her father if the civil war in Sri Lanka was a factor in their decision to immigrate, he offhandedly replied that that had never entered into their calculations. They had resigned themselves to the threat of political instability and violence since that had comprised most of their lives; their motivating reasons lay elsewhere. Ironically, these reasons are the same ones we find New Zealanders migrating to Australia citing: higher wages, the prospect of home ownership, better education, and opportunities for their children – in short, economic and social advancement. It is strange then, that the public discourse is so censorious of those desiring to settle in New Zealand for the increased opportunities it offers. We do not subscribe to this distinction at all; coming as a refugee or as an immigrant to New Zealand, or anywhere else for that matter, are both perfectly legitimate.

For us then, Labour’s policy reversal regarding immigration is fundamentally a betrayal. We do not exaggerate when we say that such a move was entirely unimaginable when we were growing up here. Processing the party’s turn has been deeply unsettling, not simply because we desire a change of government, but because it has required us to interrogate our identities as New Zealanders and immigrants in acutely discomforting ways.

It has also given us keener insight the apparent drift by ethnic minority communities which once voted for Labour en masse in favour of the now openly inclusive National, which under John Key rapidly backed away from Brash’s stance. This voter abandonment must be seen as a natural consequence, not simply of the failure to offer a clear socio-political narrative for such communities (which has been especially pronounced in the post-Clark years), but also of the subtle and blatant racism that has stemmed from the party in recent years. Winning back such voters would require more than the usual tokenistic representation but, at the very least, an unequivocal acknowledgement of the harm caused by the party’s rhetoric.

More broadly, Labour’s positioning on immigration is significant for its normalising effects. One of the country’s historically dominant parties, which for a long period was pro-immigration, now endorsing anti-immigration policies on such a scale has legitimated anti-immigrant xenophobia to a wide degree. The impact of this legitimisation is already clear. Parliamentary parties across nearly the entire political spectrum – barring United Future which fairly unequivocally favours immigration, both policy and rhetoric-wise – now all endorse anti-immigration policies in some form or the other.

The National government has already implemented restrictions on certain temporary visa categories. These changes are reflective of a particular intensification of the points system as a tool for selecting optimal migrants under the government’s watch, including through the increase of points requirements and the introduction of remuneration bands for skilled migrants. Such escalation sits particularly uncomfortably alongside the government’s preferential expedition of citizenship for ultra-wealthy individuals such as Peter Thiel. It takes a model of choosing and privileging of migrants based on nothing more than economic gain to a perverse degree. Further along the continuum, the ACT Party declares itself “pro-immigration” but only on the condition that migrants accept “New Zealand values”.

Meanwhile, New Zealand First, the party that has consistently opposed immigration, has now been emboldened to further advocate even more stringent restrictions on immigration, including cutting net migration to a draconian 10,000 per annum; “strictly controlling” the family reunion visa categories; and increasing the superannuation eligibility requirement from 10 to 25 years of residency. The party has also been empowered to double down on its racist rhetoric by going so far as to make ethnicity-based attacks on reporters whose reporting did not align with the party’s narrative.

Even the Greens, who signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Labour for closer political cooperation, proposed a policy last year of a cap on migration at one per cent of the population. Whilst they have commendably apologised for their rhetoric and policy proposals, it remains to be seen what their revised immigration policies would be. Moreover, given the Greens’ agreement with Labour; their strong reluctance to criticise Labour on the issue; and their refusal to disavow New Zealand First as a coalition partner, it is unclear what material effect the party’s change in positioning would have.

Though its policy changes and its intensified anti-immigration tack were directed by Labour’s previous leadership, they have been duly carried over by the current leadership. The use of softer language and the apparent prioritisation of other issues over immigration do not disguise the fact that their previous policies remain intact in substance.

Whilst the Māori Party has warned against blaming immigrants for social pressures, it has had to quietly revise its unpaid regional internship scheme for migrants and drop its “Kiwis first” employment policies constraining hiring from overseas and restricting temporary work visas. It also entered into an electoral cooperation pact for the election with the Mana Party, whose leader Hone Harawira has recently been advocating for the death penalty for “Chinese” drug dealers.

Though its policy changes and its intensified anti-immigration tack were directed by Labour’s previous leadership, they have been duly carried over by the current leadership. The use of softer language and the apparent prioritisation of other issues over immigration do not disguise the fact that their previous policies remain intact in substance. In fact, the party’s new front on immigration may be even more dangerous than before, as it may make the policies seem palatable or somehow acceptable on balance.

Labour’s position on these issues matters hugely given that it will be the lead party in a potential centre-left government, and its demonstrated ability to pull the political spectrum towards its position on immigration. Consequently, we feel thoroughly trapped by the options available. Even voting for the relatively clean-handed Greens seems ineffectual, as their voice on immigration is likely to be immaterial in potential post-election negotiation scenarios and coalition governing arrangements. Worse yet, the possibility that immigration policy would be a bargaining chip for an opportunistically xenophobic Labour during such scenarios remains very real. What Labour may do once in government, especially alongside a demanding partner like New Zealand First, is alarming to contemplate.

We do not want to refrain from voting like the cliché of apathetic youth, bemoaned each election but rarely taken seriously. Yet at a time when global politics is reflecting the same xenophobia that New Zealand politics seems so pleased to indulge in, we feel it would be morally abhorrent to just make the best of it and vote, as we have done so many times in the past, for “the lesser of two evils”. This time, it is unclear if anyone could be said to hold that title.

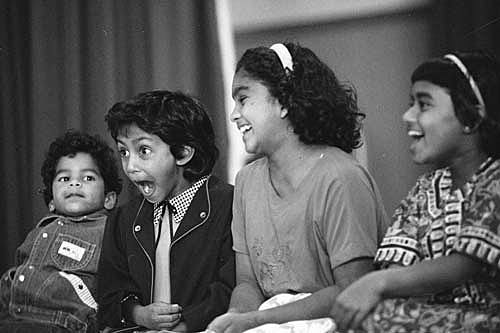

Cover Image: Sri Lankan New Year Celebrations, Paraparaumu, 1991 (Alexander Turnbull Library)