Meeting Big Bird

The sun beat down from the ozone-bereft sky over Mission Bay, where eight-year-old me tugged grumpily at the high collar of my regulation black-and-white music performance outfit.

My formal getup was complemented by the large sunhat jammed on my head: clearly favouring function over form, it was one of those desert hats with the neck flap in a very fetching shade of fluorescent yellow. It was the summer of 1994.

But if my hat clashed with my outfit, at least it matched the plumage of the superstar we’d all brought our tiny violins out to perform for: the one and only Big Bird.

My heat-induced irritation melted away as soon as I got on stage and began scratching away at the Sesame Street theme song under the conductor’s baton of my eight-foot idol (dressed for the occasion in a ruffled tuxedo bib). It remains one of the most enduring memories of my childhood.

For the last 46 years, Big Bird has enthralled generations of kids like me with his gentle nurturing and catchy ditties. He and his ragtag band of friends taught us the alphabet, how to count, what it meant to be “kind” and “loving” and how to cope with feelings like “loneliness” and “sadness”.

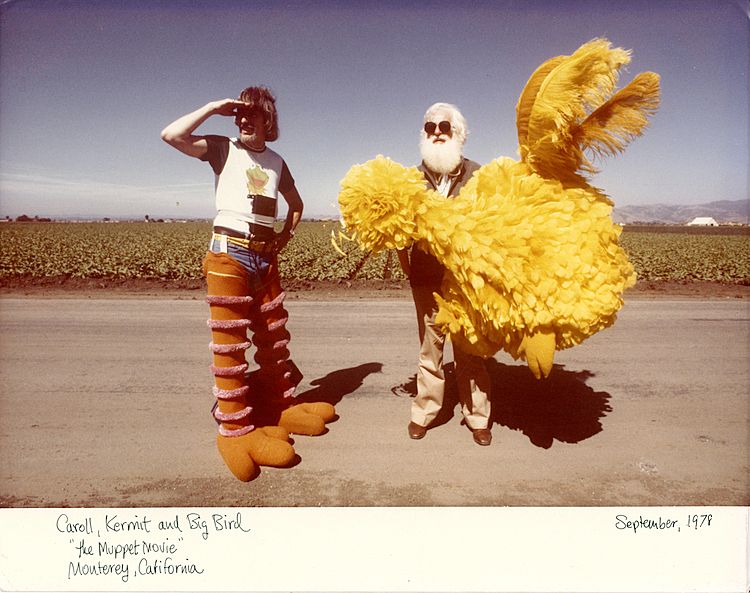

Unbeknownst to us then, the man responsible for creating our feathered friend is Caroll Spinney, now the subject of the documentary I Am Big Bird: The Caroll Spinney Story. The film draws on Spinney’s extensive home video archive to chronicle his upbringing and subsequent illustrious career with Sesame Street. The Big Bird suit, with its 4,000-odd feathers, became a cocoon within which Spinney took shelter after a difficult childhood of peer bullying and paternal abuse.

But despite being in constant awe of Muppet mastermind Jim Henson, working on the Street wasn’t all fun and games for Spinney. There was the dismal pay, the ferocious disputes with director Jon Stone, the frequently numb arm from having it constantly raised above his head to control Big Bird’s facial features.

I Am Big Bird goes to some dark places. Spinney reveals he contemplated suicide after his divorce, recalls breaking down inside the Big Bird suit after performing “It’s Not Easy Being Green” at Jim Henson’s funeral, and grapples with how he avoided death aboard the doomed Challenger space shuttle in 1986 because his costume was too big to fit on board.

But as quickly as the story dips into these difficult moments, it pops back out again, offsetting each with a lighter anecdote that lifts the tone with a reassuring, everything’s-going-to-be-okay-children pat on the back. The focus on breadth over depth makes for an easily watchable but less fulfilling story overall.

The impact of tragedy on Spinney is illustrated most starkly by what he doesn’t say, leaving the gaps to be filled by his perceptive and devoted second wife, Debra. She comes across as the more charismatic and outgoing of the pair — the Miss Piggy to his Kermit. Debra and Caroll’s relationship is a delightful binding thread of the film’s narrative and rightfully so, given their unwavering dedication to each other over the decades.

Where I Am Big Bird truly excels is in its use of Spinney’s archive footage. It shows Spinney at his most unguarded: messing around on set, joking with his wife, working on his beloved Big Bird art. It is easy to see where the character inherited his wide-eyed curiosity and open heart from. It keeps Big Bird young — he’s perpetually six years old, which Spinney often jokes makes him “the world’s oldest child star”.

I sometimes worry that I may be the world’s oldest Sesame Street fan, but the roaring success of a 2012 Kickstarter campaign proves I’m not alone. Nearly 2,000 people raised over US$124,000 to get the documentary made. Later that year, Mitt Romney turned Big Bird into a political plaything during the US Presidential campaign. He proposed funding cuts to PBS, which screens Sesame Street, and we suddenly all became very passionate about the funding of American public television.

It’s because we all remember how important the Big Bird and his friends were to us, how much we learned and loved. I watched the show again recently; it was positively hysterical and filled with strange new Muppets like Murray and Abby Cadabby. But it still has that innate ability to teach through entertaining. There are little lessons sprinkled everywhere - not just about letters and numbers, but about adopting pets from shelters and welcoming new kids to your neighbourhood.

Sesame Street’s international co-productions have tackled even meatier issues: increasing HIV/AIDS awareness in South Africa (Takalani Sesame); decreasing school drop-out rates in Bangladesh (Sisimpur); promoting acceptance between Albanian and Serbian children in Kosovo (Rruga Sesam/Ulica Sezam).

New Zealand never had its own co-production, but for a time in the late 1980s, locally produced Te Reo Māori segments replaced the Spanish inserts in the American programme when it screened here. They were directed by Michelanne Forster, who was working in the Children’s Unit of TVNZ at the time. The segments, filmed in the South Island with the Ngāi Tahu iwi, would teach lessons like “H is for Hangi,” and show children enjoying one.

Forster says depicting New Zealand multiculturalism on children’s television was groundbreaking at that time, but she felt uneasy that it was being done by an all-Pākehā team. “I think the wrong people broke the ground. The fatal flaw in the whole thing was that I didn't speak Māori; my researcher wasn't Māori although she had a degree in it. The [Ngāi Tahu] community was very helpful to us and they did whatever they could to make it happen for us, but there was a fatal lack of communication.

“It's the sort of thing that Māori Television [which wasn’t established until 2004] would’ve done beautifully and in the hands of Māori people the idea would've been properly served.”

Despite its well-intentioned attempts to showcase New Zealand culture, Sesame Street ruffled feathers among those who preferred the British model of children’s television embodied by that other Kiwi favourite, Play School, which moved at a slower pace and focused on teaching through repetition.

“[Sesame Street] was very different,” says Forster, who also worked on Play School as a script editor and director. “It used animation, the segments were much shorter - it had an element of comedy and fantasy. Sesame Street was really a lot of fun and I think it probably used the medium of television in a much more creative way. It was just like a sort of spark of light.”

“There was disapproval from some quarters that it would be damaging to children because it moved too fast. There was some concern from the educational sector because the British and the American ways of doing television at that time were quite divided.”

However, the Sesame Street way proved wildly popular and, apart from a six-year absence from New Zealand screens between 2005 and 2011, the show remains a children’s television staple.

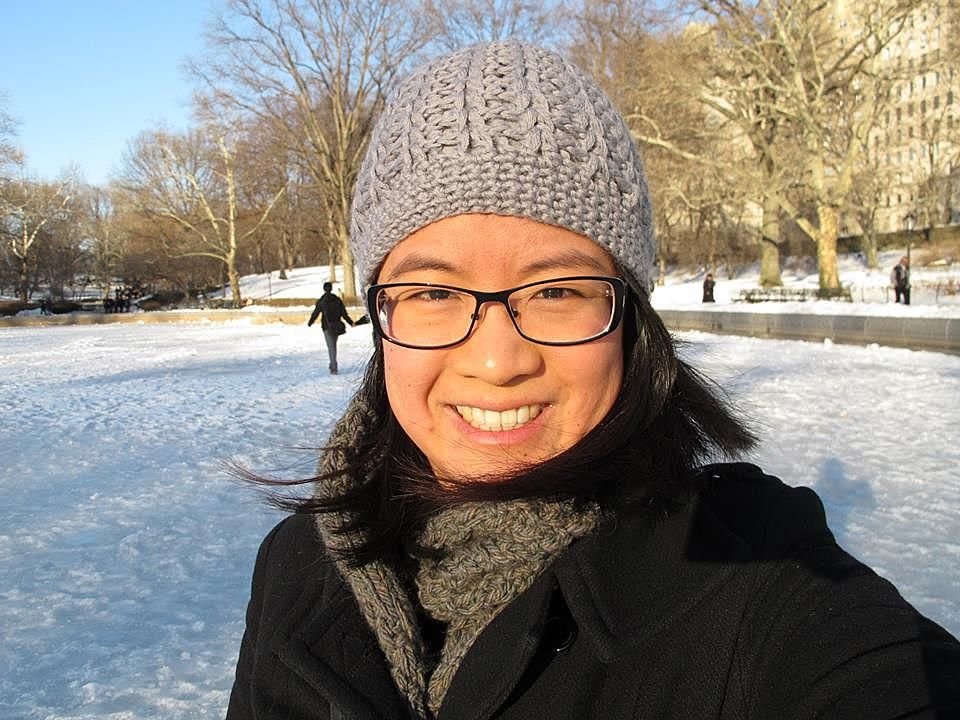

Two decades after my first encounter with Big Bird, I found myself being treated to another audience with him, at a Q&A session following a special screening of I Am Big Bird in New York earlier this year. Spinney, described in the film as a “free spirit”, was much more guarded than I expected, tired even. He quietly answered a few questions from the audience before his wife unfurled a shaggy green monster from a bag: it was Oscar the Grouch, Spinney’s other Sesame Street charge. Oscar was a crowd pleaser for sure, but also a security blanket. Nonetheless, we were enthralled.

I desperately wanted to know whether it Spinney was inside the bird suit that stiflingly hot day in Mission Bay. I knew Spinney had travelled extensively with Sesame Street, but would the American production have bothered to send the real deal all the way down to New Zealand?

I seized the chance to put the question to him during the Q&A, but was so afraid the answer would leave me feeling like I’d met the children’s television equivalent of a shopping mall Santa. But Spinney’s face lit up: “Ah, it was that very hot day!” he recalled. I felt giddy with delight.

The 1994 visit was actually just one of 18 times Spinney visited New Zealand with Sesame Street. But this trip was memorable for being one of the few times his Big Bird suit was afforded its own seat on the plane - at the discounted child fair of course.

When he wasn’t busy conducting children’s orchestras, Spinney went bungy jumping (sans costume), and drove our open highways with his wife, filming hours of footage out the car window.

“New Zealand should be on all your bucket lists!” he told my fellow cinemagoers.

All these decades later, the 81-year-old - the last original Sesame Street muppeteer - remains steadfastly committed to performing as Big Bird. Although he does less of the physical puppetry now, he still lends his voice to the character’s innocent, nasally drawl. His successor, Matt Vogel, has been waiting patiently in the wings since the late 1990s.

“I apologise to him for staying alive for so long!” Spinney quipped.

Let’s hope he has a few more sunny days left in him yet.

I Am Big Bird is released in Australia on 30 July. It will be released in New Zealand cinemas, but no date has been announced yet.