Me | We: A Review of The Platform: The Radical Legacy of the Polynesian Panthers

Navigating the space between 'me' and 'we' is both a personal and political act, writes Litia Tuiburelevu.

Although the shortest poem recorded in the English language, this couplet invites some of humanity's most primordial musings: Who is ‘me’? Who are ‘we’? And where do we connect? Navigating the relational space between the individual (‘Me’) and where one fits within the collective (‘We’) can be as much a political as it is a personal act.

For author/academic/activist Melani Anae, a first-generation New Zealand-born Sāmoan, these identity tensions imbue her most recent book The Platform: The Radical Legacy of the Polynesian Panthers (Bridget Williams Books, 2020). The book, which she describes in the introduction as both “deeply personal and highly political”, is somewhat of a genre hybrid, being one part autobiographical and one part narration of the Polynesian Panthers’ radical activism from the 1970s until today.

Anae has touched on the intersection between identity(s) and activism in two comprehensive texts: Tagata o le Moana: Pacific People and Aotearoa New Zealand (2012), and as a co-editor on The Polynesian Panthers: Pacific Protest and Affirmative Action in Aotearoa New Zealand 1971–1981 (2006), as well as in various personal essays published online. I was curious, then, about what new territory The Platform would traverse. While this book fuses various topics addressed in those other works, The Platform’s point of difference is Anae’s level of introspection. The prologue introduces the reader to three rhetorical questions that act as a narrative anchor for the remaining chapters: Did the PPP (Polynesian Panther Party) platform drive my life's work or did my life experiences drive the three-point platform and the continuing work of the PPP? Is there a difference between the two? And does it matter? Although she doesn’t explicitly answer these by the book’s end, they act as a philosophical overture, allowing her to approach issues about her identity, the Pacific community, and the Panthers’ activism with nuance.

Her burgeoning activism, then, was about finding a collective belonging in a world that posited her as ‘other’

This book is written in the first person and Anae’s writing is lucid and matter of fact. She eschews lush prose and favours a more conversational tone that gives the book a universal, inter-generational appeal and accessibility.

The Platform begins, quite literally, with ‘Me’ (O A‘I, I, ME) as Anae reflects on her teenage years growing up in inner-city Auckland. She refers to it as the ‘hood’, offering a prismatic looking-glass on a pre-gentrified Grey Lynn/Ponsonby, the first landing places for many Pacific migrants arriving in Aotearoa. Anae’s world was one cocooned in fa‘a Sāmoa: church, family and school in that order. O A‘I, I, ME is Anae’s coming-of-age story from a studious, god-fearing Sāmoan ‘good girl’ into a political activist in the late 1960s. Her activism wasn’t triggered by a specific encounter per se, rather it was the cumulative effect of bearing witness to ‘everyday racism’ levelled against herself and the Pacific community. She recalls going to the local superette on several occasions and, regardless of being first, was always served after the Pālagi customers.

I would hear the whispers and scowling looks of white customers and shop owners as I entered their space. When I entered shops, they would watch me like a hawk or follow me around until I bought something

This is an oft-repeated story amongst many children of colour whose coming of age ‘aha’ moment is realising that these occurrences aren’t anomalies but part of a larger, more insidious force that brands them as racialised bodies. Her burgeoning activism, then, was about finding a collective belonging in a world that posited her as ‘other’.

The book’s most sobering moment is when Anae describes the ‘annus horribilis’ when, at just 17 years old, she tragically lost seven family members. Anae avoids emotive language in describing her trauma, opting for a more contemplative tone to describe how her personal tragedy calcified into an internalised wall of silence.

My response was to become stubbornly quiet. I didn't want to become buried, I wasn't going to be a doctor or lawyer, I wasn't going to celebrate communion, and I wasn't going to do all the things that were considered normal or expected of a first-generation immigrant child

Her temporary rebellious phase happened to coincide with her first year at university, an environment that challenged her entrenched cultural and religious beliefs. This part might resonate with many Pacific Island students for whom higher education oftentimes severs the invisible contact obliging them to remain wholly subscribed to their communities’ ideals, beliefs and cultural traditions.

*

The book’s middle chapters act as the bridge between the ‘me’ and the collective ‘we’, as Anae explores how the Polynesian Panther Party came to fruition. The blueprint for their activism was the United States’ Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program and the writings of its co-founder Bobby Seale in his seminal book Seize the Time, as well as The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The Polynesian Panthers were acutely aware, however, that they couldn’t appropriate the Black American struggle into their experiences as Pacific people in Aotearoa, and their approach needed to be refined and contextualised. They opted for a three-point platform (peaceful resistance, Pacific empowerment and education about persistent and systemic racism), which required ‘conscientizing’ Pākehā, Pacific and Māori to understand systemic racism in Aotearoa – a tricky task when social notions of racism were largely confined to a single metric of hate speech. Furthermore, a movement grounded in inter-minority solidarity required strategic nuance and community building. For the Panthers, this also meant acknowledging their place as manuhiri and ensuring that solidarity with tangata whenua was central to their politics.

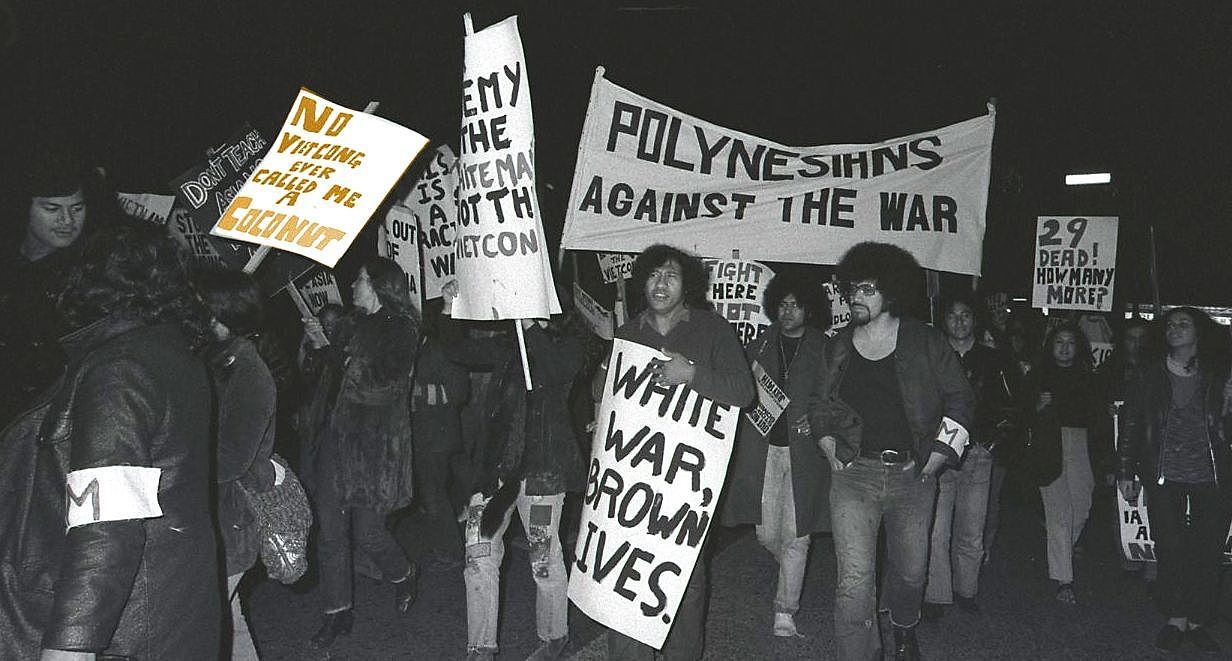

The respective gender ‘roles’ were about ensuring collective balance and nurturing of the vā

Although the PPP legacy is largely remembered through protest, their activism was firmly rooted in less politicised acts of community building; homework centres for Pacific youth, weekly prison visits, elderly care, tenancy dispute resolution, developing legal aid booklets, and the notorious PIG (Police Investigation Group) patrol. One aspect I’d like to have read more about was the women of the PPP, as too often history maligns the contributions of women of colour in activist spaces. Though the PPP legacy is memorialised through images of brown men clad in leather jackets, berets, bula shirts and aviator shades, Anae emphasises that their organisational structure shouldn’t be interpreted as ‘sexist’. Rather, the respective gender ‘roles’ were about ensuring collective balance and nurturing of the vā, with the women central to actualising the Panthers’ vision.

Anae doesn’t sugar-coat that their activism often came at a great personal cost, resulting in some deep generational cleavages between their families and the wider Pacific community. Anae dispels the myth of cultural homogeneity that is so frequently lumped on the Pacific community. Many of the young Panthers found themselves triply displaced: as racialised bodies ‘othered’ by white middle-class New Zealand, as diasporic children removed from their ancestral homelands, and censured by members of the Pacific communities who saw their activism as disrespectful trouble-making. This section, and the book as a whole, speaks to the intergenerational tension between Pacific parents who migrated across Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa and their New Zealand-born children; the former preoccupied with survival, the latter with self-actualisation. The children questioned their parent’s unwavering deference to authority, questioning why they needed to bow to a society simply because of their immigrant status. Having witnessed their community becoming increasingly marginalised, the youth felt respect could only be given when there was reciprocity and a nurturing of the vā (relational space) between the ‘me’ and the ‘we’ (in this case, society at large). As a result, the Panthers’ activism was oftentimes interpreted as countercultural, with Anae recalling the hurt of being labelled ‘fia Pālagi’ despite their ethos being rooted in service to their families and community.

Liberation can only be achieved through decolonising and re-indigenising one’s thinking

The book’s seventh chapter is a tonal shift from the more descriptive nature of chapters five and six. Anae becomes more self-reflective, returning to the fundamental question of ‘Who am I?’ following a turbulent two decades of Panthers’ activism. This chapter is very much a full-circle moment, centred on ‘aiga, her father and her first visit to Sāmoa. At first blush this chapter seems a little disjointed from the preceding sections, given its chronological shift. Nevertheless I found this section the most enlightening, as Anae moves from a place of identity tension to locating her ‘me’ firmly within the ‘we’; not as distinctive but mutually reinforcing.

*

June 16, 2021 will mark 50 years since Melani, Will, Eta, Fred, Paul, Nooroa, Eddie, Ta and Semi secretly congregated at a house on Keppell Street, Grey Lynn, to form their revolutionary youth movement. It becomes clear that the Panthers’ most enduring activist feat is their ongoing education programme (Panthers Rapp) under the maxim ‘Educate to Liberate’. Activism is not confined to the crucible years of the mid 1970s, its momentum is writ large in the classroom with the next generation. When Melani, Tigi Ness and Alec Toleafoa spoke to my elective law class a few weeks ago, they explained that liberation can only be achieved through decolonising and re-indigenising one’s thinking. Central to achieving this is firstly knowing yourself and where you hold space within the collective. In recent years, the PPP has gained renewed popularity within millennial Pacific popular culture, for example the subtle reference in SWIDT’s award-winning ‘BUNGA’ music video, in PPP merch donned by musos like Melodownz and Teeks, as well as a forthcoming series dramatising the founding of the Polynesian Panthers during Robert Muldoon’s rise to power.

Beyond popular culture, though, Melani acknowledges that the Panthers’ legacy is enduring, bridging historical and contemporary timeframes. Its power is in “its potent mixture of inter-ethnic activism in palagi spaces to annihilate racism, and intra-ethnic activism in Pacific spaces to elucidate cultural non-conformity", a sentiment as relevant now as it was 49 years ago. She ends by drawing on the potent wayfinding metaphor of walking backwards into the future, encouraging the youth to draw on their ancestral knowledge(s) in our collective quest to educate, liberate and eliminate the shackles of oppression. Power to the people.

The Platform: The Radical Legacy of the Polynesian Panthers by Melani Anae is published by Bridget Williams Books