May Fair: Texts by Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua and essa may ranapiri

Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua on Nââwié Tutugoro and essa may ranapiri on Sione Monu for May Fair Art Fair

These texts are republished courtesy of May Fair Art Fair online.

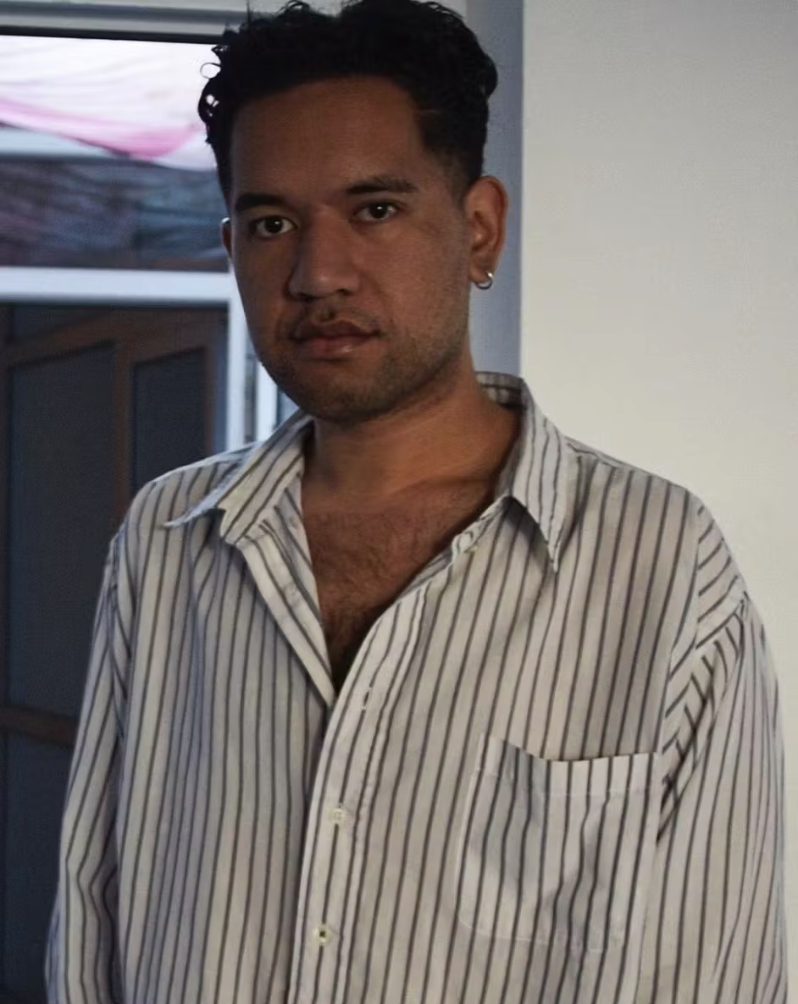

Sione Tuívailala Monū presented by May Fair

What promise, what phrase, what ancient text calls us home? And what do we do when we get there? The water is wet, the trees swaying in the breeze. An arm still quivering. You can hear them snuffling in their sties. O swine of a true believer o cliffs edge and space for all. What God breathes over the oceans, what ocean is already a God? Ready to pull that idol of Coloniser and Whiteness out from the lips of a Jewish rebel, where it never belonged? What Pacific home will bring us queers dignity? Where does it melt our bodies into sand? Islands in a slipstream. I can hear voices are they my own? I can see faces are they my home?

We are brought into a space, by Sione Tuivailala Monu. A space they have created. It is mostly white. A blank space of paleness. A white coconut tree stretches to the digital ceiling. There is a sow, her pigs are suckling, the sow is white and the pigs are white. There are coconuts strewn across the ground, they are also white. Different kinds of milk, in different kinds of bodies. There is a seat to sit on. A place to find rest, to breathe deep in the things we can taste and touch. The seat is also white.

There is a window or a simulacrum of a window looking out onto a blue sky. The only things of colour are a series of images and masks that hang from the wall. There are flowers growing from each one, a direct link to the whenua of Tonga, of Sione’s home village their tūrangawaewae, Kanokupolu. We see the name Kanokupolu on one of the masks. There is no doubt. The masks reflect the identities we wear on our faces; as a queer Pacific person these masks speak to the multitudes that we must inhabit. As a queer Māori person I think of Christmas with my family, I think of first dates, I think of going out to get bread; do I wear this mask for safety or that mask for truth? We can hide from some. We can sink back into culture. We can become inscrutable to the pākehā gaze. But we have to carry our homes, our whakapapa inside us. We can’t creep away from that.

And the white man’s touch has stretched across the Moana and has dug its roots in deep and for so long

Sione finds themselves here in this space, but also in images of this space on Instagram. The four photos on the opposing sides of the room speak to this, images of their trip to Tonga. We can build an identity online an identity that is still tied to whenua, still tied to the land. Sione has found their confidence through the online has reclaimed their identity in this private yet so public space; something I identify with myself. There are so many things I would not know about myself without the internet and social media, but they are still ideologically loaded. The whiteness in the room speaks to this; we can find ourselves here but it isn’t what the pixels want, a few rich white men who care nothing for indigenous lives have constructed this space. And the white man’s touch has stretched across the Moana and has dug its roots in deep and for so long. This can be felt in the queerphobia that emanates from those in power in Tonga this is the mark of the white invader which has whitewashed what was once a culture of acceptance. The legacy of a certain distorted Christianity.

There is no movement in the space but it would be easy to imagine it, the pigs snuffling and the leaves blowing in the breeze, the salt air and water lapping against the beach, the coconuts pivoting where they lie swinging ovoids, they almost look like eggs waiting to be cracked waiting to hatch. There is a nervousness here that is childlike. Where do we grow up and how hidden must we be when we do? There is a light, halogen bars, form a twisted rectangle sun on the ceiling where the light scatters through the trees. We are many things at once, twisting in the white haze. The colour of the masks and the photos speaks to the stillness as it cuts through it, oh how we standout and how brave we are to claim both queerness and indigeneity in doing so! Oh here we are and don’t you dare ignore us!

-- essa may ranapiri on Sione Monu

Nââwié Tutugoro, cassette tape garden recorder, 2020

Nââwié Tutugoro presented by May Fair

'cassette tape garden recorder' is an image of a dream. It collects, forages, extracts, imagines, mythologizes, and yearns. It memorialises, as both elegy and as ode. It is excessive and meandering and playful. It is a house and a womb.

I sit with my friend in this house for months–years–and she explains her life to me. Nââwié Tutugoro was born on the hottest day of 1993 in the back garden of a Grey Lynn villa, a water birth baby. There is sugarcane there, sourced by her father and propagated for his family to sit with and be shaded by, to munch on and contemplate alongside. There are oak leaves too, drifting in from the roadside as a perhaps unwelcome guest, but a guest nonetheless. And then there is the hot tub, an anomaly amongst all that lush green and brown earth, the literal birthplace of the artist. It has warm waters. An extension of the womb and a canal for mother and child to swim in and be held by. It bubbles and swirls and spits. It is life and potentiality.

I speak with my friend about her intentions in attempting to replicate her memories, about rendering them into a sort of digital living quarters. I am reminded of a story she has told me of her father constructing a ‘grande case’ in the back garden where she was born, an ancestral form of ceremonial architecture or dwelling that is specific to the Kanak peoples. He collected and foraged materials from their surrounding neighbourhoods and erected from memory the impressive structure. Like the planting of sugarcane, the grande case locates her father and his family in Kanaky/New Caledonia via Grey Lynn, and vice versa. It acts as another portal to life and its endless potentials, to places seen and unseen, visited and missed. I can tell through her recollections of its building how proud her father was of his achievement, he beams while presenting his work for the camera. There are images of him hosting friends and loved ones over kava, much like Nââwié has hosted me in her house these past few months and years.

Nââwié Tutugoro was born on the hottest day of 1993 in the back garden of a Grey Lynn villa, a water birth baby

I visit the house more frequently and am introduced to other symbols and artefacts that she has rematerialised. She tells me of a mural painted on the family garage exterior in 1998, a joint exercise between father and daughter to mark support for the Nuclear Free Pacific movement. In this house it is abstracted. Its waves flow as blue lines, misty frequencies set in chunks of black. There are also two prints the artist has drawn as a child, one depicts a vase of tendrilous flowers and the other is a portrait of her father “when he had hair.” They are titled ‘boy drank all that magnolia wine’ and ‘mon père cool’ respectively. In this house they are satin towels floating on either side of a washing line, more whimsical than they are functional. They are images, memories reformatted and repurposed in the logic of her dreams. And then there is a Persian rug, the surface upon which her grandfather died and her little brother was born. It holds the hot tub, her birth canal that bubbles and swirls and spits.

There is so much in this house–it is excessive. It exceeds language to produce its own vernacular, defying the strictures of mere ekphrasis or the limited context in which it is presented. It acts in its own logic much like dreams and memories and traumas and joys do. My friend would like you to sit in her house, her grande case, her dreams. To come inside like how the weatherboards and the oak leaves and the sugarcane and the earth has. To perhaps sing a song, hum a tune, or say a prayer. To feel welcomed and loved and at home.

-- Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua on Nââwié Tutugoro

May Fair Art Fair

11th-25th September

Feature image: Sione Monu