Ka Hao Te Rangatahi: On the Nets of Matthew McIntyre Wilson

Can the ruptures to whakapapa be healed through the weaving of nets?

Can the ruptures to whakapapa be healed through the weaving of nets?

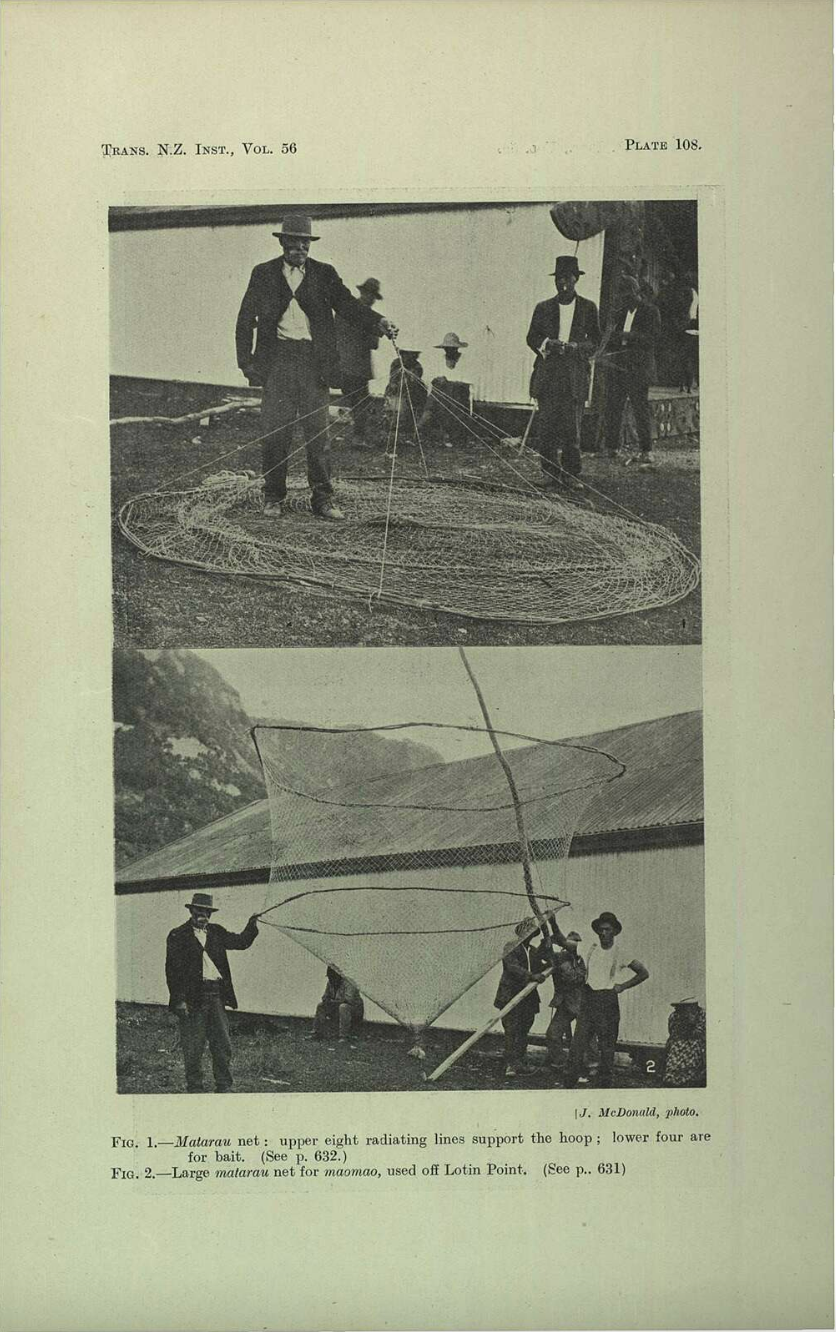

In a photograph taken by J McDonald in the early 20th century, reproduced by Te Rangi Hiroa (Peter Buck) in his 1926 book The Maori Craft of Netting, a moustached man – well put together in a jacket, shirt and tie – looks straight toward the camera. The photograph is tightly cropped, only just accommodating the peak of its subject’s hat, and gives up its entire bottom half to a large, netted structure upon which the man stands. Strings rise from the perimeter of the structure to reach an apex in the man’s outstretched hand. Enough fabric is bunched on the grass for it to be clear that, were he to raise his hand further, the net would continue to expand.

We are not the only audience to this scene. Behind the moustached man, people gather around the outside of a wharenui. Though most are engaged in their own activities, one man – alone and to the side – is caught up with us in the act of looking. His gaze, like ours, fixes on the man atop his net.

In the next photograph, printed below the first, the frame opens up. We are able to see the landscape: a white stretch of sky, the bank onto which the wharenui backs. The subjects have also shifted – the moustached man and his observer, who has removed his jacket, each rest a hand on the net, now fully extended. Two more men gather together to support the long wooden pole which holds the net to height. Standing beside this floating, woven mass, both the men and the wharenui are dwarfed.

I can tell you the name of the moustached man, but not the others. He is Horepa Piri, who at the time of photographing had recently returned from Lotin Point, where the net had been cast, to Te Araroa, where his methods were recorded by Te Rangi Hiroa, and his catch cooked and shared. Because this net is used specifically for catching mātā, and their season runs from the end of January to the beginning of April, we can assume the photograph was taken in the early months of 1923 – the year Elsdon Best, McDonald, Johannes Anderson and Hiroa made an ethnological expedition to Ngāti Porou land, on the east coast of Aotearoa.

They do not, for example, convey the earthy scent the kupenga give off

As much as these photographs tell us, details are lacking. They do not, for example, convey the earthy scent the kupenga give off. I walked into Matthew McIntyre Wilson’s (Taranaki, Ngā Māhanga and Titahi) The New Net, installed in SOLO 2018 at The Dowse, and ran straight back out again. “Arie!” I called excitedly through the galleries, “Come smell this!”

McIntyre Wilson has, as the accompanying wall text reads, “been learning the craft of ta kupenga…[He] approaches the knowledge of the craft as a taonga, concerned with learning not only the skills to produce various fishing nets, but also the history of net makers and how nets were used in everyday lives.” The New Net comprises two examples of the artist’s craft: a matarau, the same form of kupenga Piri unravels in McDonald’s photographs; and a hīnaki purangi, used for catching tuna and upokororo.

The kupenga, which are at the same time looked at and looked through, play a game of catch and release, entangling the viewer in their contours

Also listed on the wall text are five materials: harakeke, kareao, whale bone, muka and kōkawa. Harakeke, carefully selected and partly dried; kareao, a climbing vine; and muka, two-ply strands of scraped fibre, are the materials from which the kupenga are constructed and which carry the heavy scent through the gallery. The whale bone, which is displayed in a small vitrine, has been carved into au, or threading-needles. Kōkawa is also known as andesite, the volcanic rock that hangs as a weight at the base of McIntyre Wilson’s matarau.

Hung in the gallery, McIntyre Wilson’s nets are disorienting. They cast webbed shadows onto the walls and floor, upending the viewer's sense of space by turning the small room in which they are displayed into a vessel. It is clearly no accident that the gallery seems almost to take on the qualities of a body of water – looking up at the roof, I half expected to glimpse the sky, the grey concrete floor like sand beneath my feet. Each kupenga demands a different kind of viewing: the hīnaki purangi, which is long and thin, is displayed stretching horizontally through the room. It feels – it is – lighter than the matarau, for it floats far further from the floor. The matarau, which stretches from ground to ceiling, weighed down by a stone at its base, draws the gaze up and out. The effect, for the viewer navigating the space between, is one of submersion. The kupenga, which are at the same time looked at and looked through, play a game of catch and release, entangling the viewer in their contours.

The New Net grants a presence to Hiroa’s research. It would be easy to assume, upon picking up the damaged and water-stained copy of The Maori Craft of Netting from the library, that the practice is by now confined to the pages of history. The text slips between past and present tenses: “The methods of procuring fish were based upon the careful observations of generations of fisherman…” seems to place the craft firmly in the past. Meanwhile, other observations – “The tugging of the fish at the bait can be distinctly felt on the line” – and the illustrating photographs, speak to the nets’ contemporary use.[1] This is the ethnographic problem: in creating a record for posterity, the discipline freezes its subject in a timeless past. This is not to say that Hiroa was unaware of contradictions in his work, but that although the origins of anthropology lie in the imperial expansion into – and subsequent examination of – ‘new worlds,’ its methods have been interpreted by some, including Hiroa and his colleagues Apirana Ngata and Hirini Moko Mead, as tools for cultural recovery.

... It was something we Polynesians have lost and cannot find, something that we yearn for and cannot recreate

In an anecdote recounted in Rangihiroa Panoho’s Māori Art: History, Architecture, Landscape and Theory, Hiroa recalls the disappointment he felt on arriving at Taputapuātea, the marae at Opoa, Ra’iātea – known to anthropologists as the centre of the ‘Polynesian triangle,’ and by a number of Polynesian cultures as Hawaiki.

We took pictures of speechless stone and inanimate rock. I had made my pilgrimage to Taputapu-ātea, but the dead could not speak to me… I felt a profound regret… It was something we Polynesians have lost and cannot find, something that we yearn for and cannot recreate. The background in which that spirit was engendered has changed beyond recovery. The bleak wind of oblivion had swept over Ōpoa. Foreign weeds grew over the untended courtyard, and stones had fallen from the sacred altar of Taputapu-ātea. The gods had long ago departed.[2]

Here, the “I was there” that is usually so central to the ethnographic register becomes “I did not hear.” Of course, the processes through which field trips such as Hiroa’s worked to record the customs and cultures of societies have always effected change themselves. The trouble, in this instance, is Hiroa’s conviction that he has arrived too late. If the allegorical foundations of ethnology rest, as James Clifford claims, on the irresistible image of the ruin, then at Taputapuātea, Hiroa was forced to confront that.[3] But how does one move past it?

“We are all,” writes Albert Wendt, “in search of that Heaven, that Hawaiki, where our hearts will find meaning; most of us never find it, or, in the moment of finding it, fail to recognise it.”[4]

In another photograph, this one reproduced in Māori Art, Paratene Ngata demonstrates the construction of te hīnaki. He sits on the ground, one leg tucked beneath the other, looking intently at the thread running between his two hands. To his left sits Johannes Anderson, whose eyes track the passing of the thread through Ngata’s hands. Left again is Hiroa, cigarette in mouth, taking notes. Between the three men rests the hīnaki.

Looking at McIntyre Wilson’s kupenga, I think of their whakapapa. I think of the artist’s eyes passing over these photographs, reading Hiroa’s text, seeking out kupenga in communities and in museums, reflecting on their use and disuse. I think of the many kupenga that have been cast into water; the animals they have snared. The hands that worked them into being; the plants that made their existence possible. I wonder, standing in the webbed shadows of The New Net, at how language fails me; I try to imagine a way to differentiate between outcome and process, object and whakapapa.

It seems impossible not to be moved by the materiality of the kupenga

“Ka pū te ruha, ka hao te rangatahi,” goes the whakatauki that translates into English “as the old net is cast aside, the new net goes fishing.” The New Net Goes Fishing, Witi Ihimaera’s second collection of short stories, published in 1977, draws its title from the whakatauki; as does McIntyre Wilson’s work. In ‘Gathering of the Whakapapa,’ a story included in Ihimaera’s collection, an unnamed mokopuna watches on as his grandfather, Nani Tama, works to reconstruct a record of their whakapapa which was lost in a fire. As he recounts:

[Nani Tama] had begun to rewrite the village family genealogy. He had started to re-establish our links not only with our past, but also with our land and with each other in the present. Although we would always be bereft of those other village treasures consumed in the fire, our history as revealed to us through our whakapapa could still be reclaimed. There was time yet, time yet to dig again our toes into the earth and shout our challenge to the changing world: This is us, this is our history, this is our land, and we together are the tangata whenua, the people of this land.[5]

Like McIntyre Wilson’s work, Ihimaera’s passage speaks to a concern with the materials through which “history is revealed to us by” and knowledge is made tangibly present. It seems impossible not to be moved by the materiality of the kupenga. Their construction – a dizzying matrix of knots – is testimony to the craftsmanship Hiroa sought to record in his research. And although the hīnaki purangi and matarau exhibited in The New Net are contemporary, and although the fibre from which they are made is far younger than the knowledge of the craft which Hiroa sought to capture, they carry with them the history of their use.

*

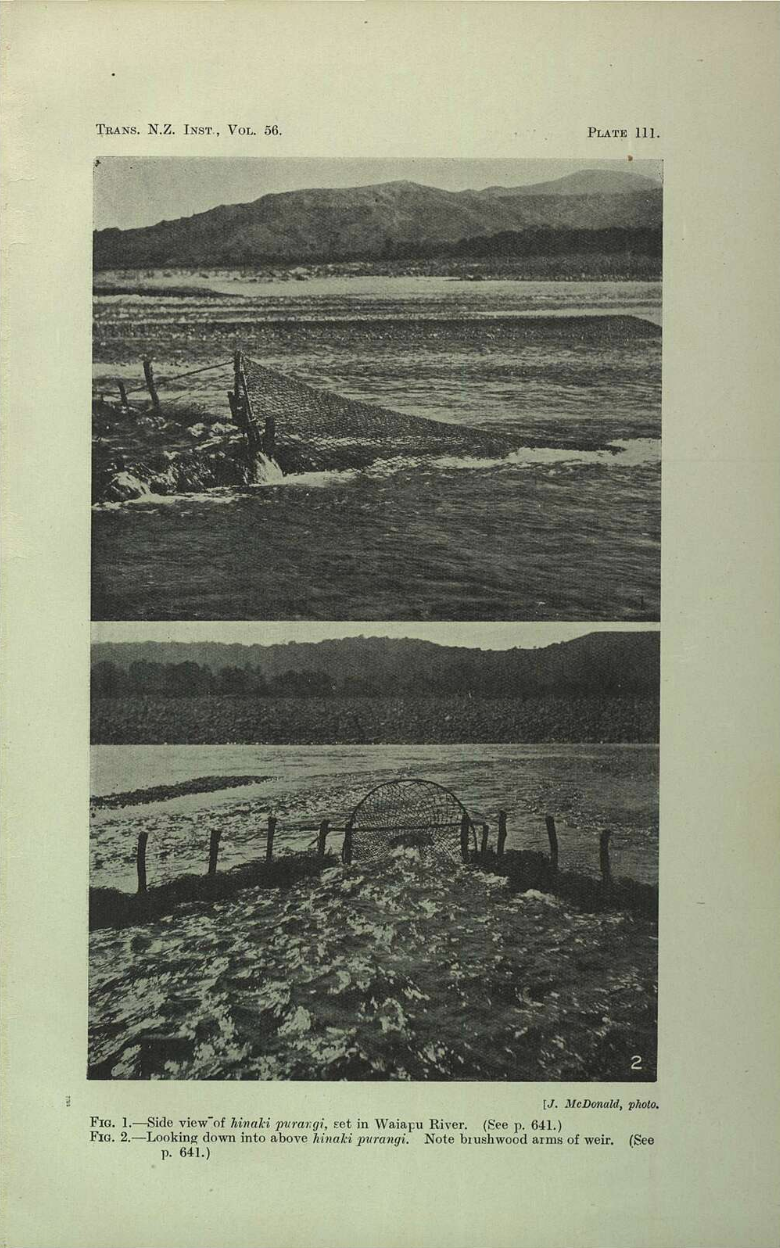

One more photograph. In this one, we look down the barrelled entrance of a hīnaki purangi, set in the Waiapu River. The river’s current sweeps right down the centre of the net. Water extends from the bottom of the frame, giving the impression that the photographer is getting their feet wet. The little fish, hiding beneath the opaque water, are being swept down into the finely meshed end of the net. “There,” Hiroa tells us, “they are packed like sardines by the force of the water, and not even eels can turn back: they speedily die.”[6]

Image from the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa.

What I’m trying to gesture to, in placing The New Net in conversation with these texts and images, is the stories woven into the fabric of the kupenga, for their presence in the exhibition is pervasive. They represent a rebuke to the assumption that there is an absolute difference between material and immaterial culture. Instead, they argue in their various ways, each begets the other.

In this way, museum stores reveal... that collections are assemblies of relationships, where every connection made carries with it an initial rupture

McIntyre Wilson has regularly re-approached, or re-examined, cultural practices – of both construction and collection – in his practice. The exhibition Matthew McIntyre Wilson & Maker Unknown, held at Pātaka Art + Museum in 2014, placed examples of the artist’s weaving alongside works attributed to “Maker Unknown,” speaking to the murkier corners of museum collections and the processes by which they can effect change while ostensibly working to acquire timeless relics of a historic past. In the exhibition’s catalogue, Dr Huhana Smith wrote that “there are two makers in this exhibition as McIntyre Wilson releases aspects of that former creative, human potential from silenced binds.” He does so by taking material seriously: examining the physical composition of objects without clear provenance as a way of engaging directly with the things he wants to understand. I’m thinking now of my friend and mentor Matariki Williams, who has written previously that “We’re always told how whakapapa represents the ways that Māori are connected, what is not mentioned is how it reveals what we’ve lost." In this way, museum stores reveal – as Matthew McIntyre Wilson & Maker Unknown pushed for the gallery space to illustrate – that collections are assemblies of relationships, where every connection made carries with it an initial rupture.

Much has been said about the ‘decline’ and subsequent ‘revitalisation’ of Māori art; enough that I do not feel any compulsion to rehash those arguments here, nor to point toward the complexities of such language. What I admire most in McIntyre Wilson’s work is the way it is situated firmly in a Māori intellectual tradition, that it can be traced through a history that is fraught, divisive and Indigenous. His kupenga come out of this history and into the contemporary art gallery, to exist on their own terms: to be as much themselves as they are those that came before them.

[1] Te Rangi Hiroa, The Maori Craft of Netting (Wellington, NZ: Govt. Print, 1926).

[2] Hiroa quoted in Rangihiroa Panoho, Māori Art: History, Architecture, Landscape and Theory(Auckland: David Bateman, 2015), 151.

[3] James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Allegory,” in Writing Culture, edited by James Clifford and George E Marcus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 98-121.

[4] Albert Wendt, “Towards a New Oceania,” Mana Reviewvol. 1, no. 1 (1976): 49.

[5] Witi Ihimaera, “Gathering of the Whakapapa,” in The New Net Goes Fishing(Auckland: Heinemann, 1977), 28-29.

[6] Hiroa, “The Maori Craft,” 641.