Marking a Return

Mokonui-a-rangi Smith recounts his experience of learning tā moko with his mentor, Croc Coulter. An extract republished from Past the Tower, Under the Tree.

Essay republished from Past the Tower, Under the Tree: Twelve Stories of Learning in Community edited by Balamohan Shingade and Erena Shingade, published by GLORIA Books.

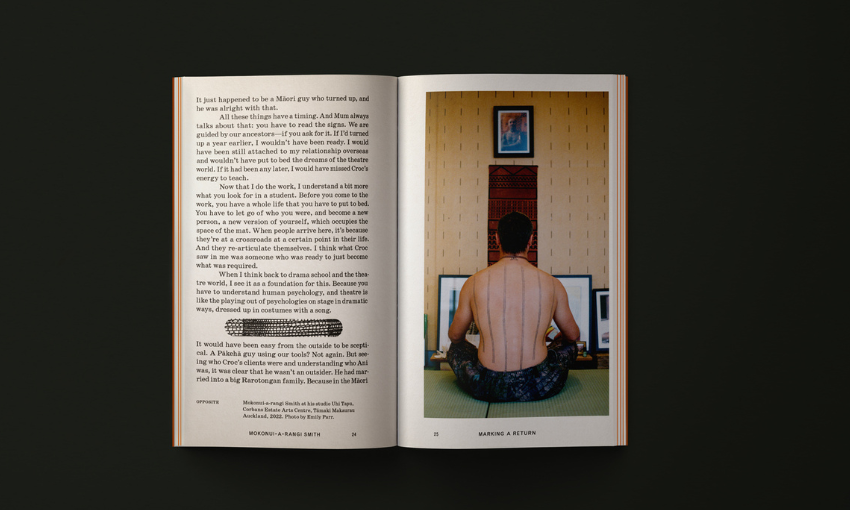

Pages of 'Marking a Return' by Mokonui-a-rangi Smith in Past the Tower, Under the Tree: Twelve Stories of Learning in Community.

The first time I met my teacher was because of an art project. My cousin asked me to help with a project in Rarotonga called the Oceanic Performance Biennale—a kind of a wānanga space for performance artists and scientists to come together and talk about climate change. My cousin couldn’t make it in the end, so I had to represent her when I arrived to meet the person on the ground, Ani O’Neill. Although I didn’t know who this Cook Island artist was till that point, it felt like some kind of divine intervention thing, because for a couple of years before that, I had been following someone who turned out to be her husband: the tattooist Croc Coulter. Everything that Ani and I did for the Biennale was in their lounge, and Croc would be in the corner doing his drawings for the next day’s tattoo.

In my time following Croc on social media—on YouTube and Instagram—and through other people’s stories, I had been quite intrigued and challenged by him. Here was a solid practitioner, who made beautiful work, but was from England and living in Rarotonga. There were too many abnormalities there to get my head around. But I also felt that there was something very genuine. Other common friends said, ‘Man, if you’re really interested in learning that stuff, you have to go talk to Croc. He’ll be good for you.’ After a few people said that, I thought, ‘Oh, all right. Maybe I should.’ People vouching for him were Samoan, Māori. So, for a long time I had been wanting to meet him. And while I was working with Ani, just seeing the tools in action was mind-blowing. It really touched me.

Towards the end of the trip, I said to Croc, ‘I want to show you these’. I opened my bag and unwrapped a set of tools that I had spent a couple of years making. I had been crafting them, and trying them out on myself, and trying them out on tattooers—just trying to work it out. As I unwrapped them, he kind of looked at me differently. It was like we had entered a whole other situation. Other people were interested in his work, but nobody else had ever turned up with tools. I was the first.

I had been quite intrigued and challenged by him. Here was a solid practitioner, who made beautiful work, but was from England and living in Rarotonga.

Croc considered the situation. We talked about him tattooing me before I left. After some time, he laid out an offer for me to learn to use the tools. He said that if I wanted to learn to make the tools properly, and use them, I could come and live with him. It would take a minimum of three months, but we could begin the process, and take it from there.

That was it. His offer felt surreal—like something out of a movie. A beautiful narrative that you always hope for, but you never expect. I was flying back to Auckland the next day after having my leg done, and I promised to go and get organised.

***

I came home. I was enrolled at the University of Auckland to do some papers on Māori material culture, thinking I needed to go down a material cultures study path. Or go into acupuncture—it was one of those two.

I’d recently come back from overseas, where I’d worked for a theatre company. I’d been through drama school and done a couple of years’ work, but I was finished with it. I had gone deep into the space of theatre, to the point where I wasn’t there for the same reason as everybody else. They all wanted to be actors. I didn’t know what I wanted to be. I thought I wanted to be an actor, but maybe I was better off as a director? Maybe I just wanted to tell some stories in Māori. Maybe I was there because people had told me to do acting for years. Intellectually, I was inspired by it. But I knew that there was a limit to my energy in that space.

When you have a sense of adventure, you are inspired. If you’re excited, then that energy carries you through the struggles.

When you have a sense of adventure, you are inspired. If you’re excited, then that energy carries you through the struggles. In the earlier days when I was working and living with a theatre company, there was a self-sustained energy, because it was so awesome. But it was also because I had no responsibility—I was just experiencing it.

At drama school, we had to make a performance every week to show to the school. It was a grinding process, with big ups and big downs—a pressure cooker to make, make, make, make, make, make as many mistakes in front of the teachers as you can and get feedback. Teachers and students would say, ‘That didn’t work. Why? Why not? Try it again.’ ‘Now, did it work? Okay, do it again.’ It’s a high-friction space, and you either come out super sharp, or you come out dull. And through the process, I learned I didn’t want to be an actor. It wasn’t what I was looking for.

For those years, I had set myself up to meet the teachers of the theatre world. I lived and worked with one of them. And they’re incredible—literate, deep thinking and creative. But after seeing it and being with it enough, I started to think that perhaps it was the people that they were writing the plays about that attracted me more. I needed to find who those characters were in real life.

I didn’t want to keep making things that are ephemeral. You can pour your heart into something for a couple of weeks and do a performance, but then it’s gone.

I also learned that I didn’t want to keep making things that are ephemeral. You can pour your heart into something for a couple of weeks and do a performance, but then it’s gone. Totally gone. You’ve got nothing to show for it. Then you work with another director and start again from zero. None of what you did in the previous performance carries over. If the applause feeds you, then you’ve got the energy for it. And if you’re a good craftsperson and you take pride in your acting, then there’s energy for it.

For me, I felt like I was losing energy. If you’re being supported financially, you can get away with doing something that is not quite the right path. Getting paid is its own incentive, but theatre doesn’t pay your bills. All those old mates of mine are still broke in their forties and fifties. None of them can afford to have kids, none of them can own a house. If I wanted to keep going with acting, I had to commit to a move to London, or if I wanted to go and film, LA. And I doubted whether I was still invested enough to move to either.

I finally made the decision to hurry up and retrain before I ended up too far down the track. I had to leave my partner who was over there to come back home and start my life on my own terms in a direction I really wanted. A lot had been left behind. When we think we’re on a linear path, it’s easy to get stuck in a certain idea. It can be hard to let go of the sense that you have already invested so much time, tried to develop expertise, been given opportunities. It is freaky to turn away from it.

When we think we’re on a linear path, it’s easy to get stuck in a certain idea.

Given the situation, it felt like whatever I chose to do, I was going to have to come at it with 150 percent, and just become it. It was so late—it felt like a situation of ‘now or never’. I had a kind of infinite energy, like a slingshot that was fully drawn back. Point me in the direction, and I’ll fly that way.

When I got back from Rarotonga, I went into the university and un-enrolled. I packed my bags, saw the whānau, cleaned up my bedroom. Five days later, I flew back to Rarotonga.

Photo supplied by Mokonui-a-rangi Smith

The beginning of the apprenticeship was the coolest thing. Croc had given me a list of things to bring: materials like pigs’ tusks, and certain tools I needed, so I brought them and laid them out. He then asked whether I knew how to weave. I didn’t, so we began from the beginning, making kikau blinds. We took a machete, climbed up a ladder and cut some coconut fronds down. We sat and spent two days weaving panels which would then be strung up as the walls for the tatau hut. The panels were quite textured and created beautifully dappled light. They let the wind through, but not full gusts. There was a moment of recognition when I thought that I’ve heard of this—when the teacher doesn’t teach you what you want to learn. They go around the other way, and they teach you other stuff first.

I liked the way Croc created that space. It was a way to warm up, feel each other out, and get talking. He wasn’t giving away anything too quickly. And from out of that space came resonances, like when I remembered that my mum’s a weaver, or that my koro and kuia were weavers. And Ani’s an expert weaver.

We started to build our relationship and get to know each other. We were looking after the hut before we got started, looking after the place where all the work and learning was going to happen. That was beautiful and I took note.

The day-to-day was relaxed. There was lots of drinking tea in the morning and then our first task would be to go and sharpen the tools and clean up the hut. We’d talk about technical stuff there—materials, processes for making tools. We stuck to toolmaking to start with.

When the teacher doesn’t teach you what you want to learn. They go around the other way, and they teach you other stuff first.

And then it was lunchtime and the heat of the day, so we often went into town and did some shopping or ran some errands. Or we’d have a client. I’d cook everyone lunch and then go and join them to do the stretching. I learned to stretch with Croc—to occupy that job and learn all the stuff around how to manage the body, how to stretch the skin properly, how to clean up the ink as you’re going along without wiping away the design, how to look after the client and maintain the energy while Croc’s focus is somewhere else. In the late afternoon or early evening, we’d clean the tools and do the maintenance before watching a movie and doing a bit of drawing at night.

It was amazing how industrious Croc was. Every day, he was making, making, making. Alongside our practice, we built an Airbnb house on their land, so we were going back and forth building for eight hours a day. If Croc wasn’t building, he was drawing. If he wasn’t drawing, he was fixing his motorbike. If he wasn’t fixing his motorbike, he was tattooing. Or he was recovering to do one of those jobs. He never stopped. Coming from drama school with a really strong work ethic, I was down with that. It was a pace of life I loved.

What was amazing was how Croc could maintain that pace even though his energy levels were super low. He struggled a lot and had painkillers to do what he did. But he inspired me with a concise use of energy and a real ability to relax—when he was drinking a cup of tea, he was drinking a cup of tea. He was able to bring full focus into the tea, and then into the tattooing, and not have the energy lag and bleed into each other. It taught me to relax. He would tell me, ‘Hey, just chill. I know it’s hard when you come from the city, but you will learn to slow down.

He inspired me with a concise use of energy and a real ability to relax—when he was drinking a cup of tea, he was drinking a cup of tea.

I live like that more and more now and I’m grateful for it. But I think a lot of it comes from the intensity of the work—it’s a full focus, and yet, it’s a soft focus. You can’t be stressing, because it will influence the experience of your client—you can’t have that effect on them. I’m sure he got that stuff from living in India—a culture that knows meditation, and pace, and appreciation. He was able to bring it into the tattoo world.

I also had to do a lot of yoga for the first few years to be able to sit down for so long. I definitely couldn’t do this work without it. Croc’s mum was a yoga teacher. Back in the ’70s, she taught yoga in prisons. So there is a level of mindfulness, or whatever you want to call it, that grows with the work. After you live like that for a few years, it shapes you.

Croc was dedicated to maintaining the art form to a beautiful standard. He was completely covered in ink, head to toe, which was his self-dedication. During that time, it felt like I was living completely within the womb of learning—being under someone, reforming myself, reformatting. I had stepped out of my environment, and all its distractions and all its needs, and just made myself totally free for this apprenticeship. I based myself in his context and we started from the beginning: I didn’t know things, I made mistakes, I had to be humble, I had to make myself available, put in that energy of being in service for someone. And the reciprocation is that they are teaching you stuff.

It felt like I was living completely within the womb of learning—being under someone, reforming myself, reformatting.

It’s not at all like the education we’re used to—a nine-to-five class with a methodical layout and homework: ‘You will come out with this, if you do this.’ There is none of that. You learn all the human stuff and the business stuff and the craft, all at once. It’s super fluid.

Learning with Croc, I had the feeling of homecoming, like I had finally found a thing, an art form or a craft, and a way of life, which I had been looking for my whole life but didn’t really have the confidence to admit. Usually, you don’t think you’re worthy of doing such special things, but you think other people are. Seeing and hearing the tools in action, and then receiving the work on my leg, felt like a marking of a return to the Pacific Islands. The home of our ancestors. We were marking that history just up the road from our waka, which many hundred years ago went through that channel on its way to Aotearoa. Our ancestors were on those beaches, repairing the waka, feasting. It felt like a special level of reconnection. And then to be offered a kind of a continuation, and an invitation, into that world…

Photo supplied by Mokonui-a-rangi Smith

You don’t plan any of this stuff. There’s a Western system that lays everything out for you in a pre-planned way so that you’re guaranteed that if you do x, you get y. Or ‘you’re going to learn this thing after this course’. With a process like that, you can line yourself up for certain jobs, be able to save money and achieve certain goals. It’s understandable—everyone needs some sense of security and a sense of a channel to build life around.

But I have always been attracted to finding out what you’re really about—a way of being open and in tune and seeing how you can meet people who are going to align with that. My dad used to read us books about Zen teachers and martial artists in Japan, who often leave what they know in order to go find someone who knows what they want to know.

My immediate whānau had laid the foundations for this from the beginning. Not in a projection of me into the tattooing world, or even the fine arts world, so much as a sense of culture and appreciation. All the discussions we used to have growing up helped me develop an enquiring mind, a mind that searched for something of proper value. One of the things my mum and dad talked about was the need to find something to give back to the culture with, to be inspired by, to be faithful and creative with—to try and work all those levels at once.

There was a beautiful kind of harmony, too, in that my name carries the craft as one of its meanings.

They made me into a person who was ready to go find a craft, so it made sense when I decided to go back to Rarotonga. There was a beautiful kind of harmony, too, in that my name carries the craft as one of its meanings. Although it’s a whakapapa name that links us back to a maunga from the East Coast, there are a few translations that relate to tā moko. When Croc held out the offer to me, we could all appreciate that names can have an effect—they can shape you and guide you if you’re open to it. Learning tā moko is not the kind of thing you want to ask for. It was a direction that Croc offered to me, which, in a way, feels even more significant.

He had been waiting for a student. But for a long time, he didn’t want to teach because he didn’t feel like he had that right. And then towards the end, he did want to teach because he wanted to give the tradition back, and make sure it stayed alive in the Cook Islands. It just happened to be a Māori guy who turned up, and he was alright with that.

All these things have a timing. And Mum always talks about that: you have to read the signs. We are guided by our ancestors—if you ask for it. If I’d turned up a year earlier, I wouldn’t have been ready. I would have been still attached to my relationship overseas and wouldn’t have put to bed the dreams of the theatre world. If it had been any later, I would have missed Croc’s energy to teach.

When people arrive here, it’s because they’re at a crossroads at a certain point in their life.

Now that I do the work, I understand a bit more what you look for in a student. Before you come to the work, you have a whole life that you have to put to bed. You have to let go of who you were, and become a new person, a new version of yourself, which occupies the space of the mat. When people arrive here, it’s because they’re at a crossroads at a certain point in their life. And they re-articulate themselves. I think what Croc saw in me was someone who was ready to just become what was required.

When I think back to drama school and the theatre world, I see it as a foundation for this. Because you have to understand human psychology, and theatre is like the playing out of psychologies on stage in dramatic ways, dressed up in costumes with a song.

***

It would have been easy from the outside to be sceptical. A Pākehā guy using our tools? Not again. But seeing who Croc’s clients were and understanding who Ani was, it was clear that he wasn’t an outsider. He had married into a big Rarotongan family. Because in the Māori sense, once you marry in, and if you adopt their way of living, you’re not just the married guy who holds to your own ways. You are adopted and it’s a different situation.

Over time, I heard how Croc had learned from Inia Taylor. He had lived with Inia, and through that he adopted and adapted to Inia’s world. Earlier on, he had been in India for about eight years, living in little villages and caves, staying in temples. Again, he had adopted and adapted. And I think all of that gave him a very… Indigenous feeling. Although he wasn’t Indigenous, there was a spirit of doing things which was very of the earth and of the community. He always wanted to know how the local people did something so he could do it properly. When Ani and Croc got their land in Rarotonga, they planted a coconut in each corner.

You have to be seen working the land, doing some mahi kai collecting or processing, or else you’re just another Pākehā guy who comes and holidays.

Another part of being accepted on the island is gardening. You have to be seen working the land, doing some mahi kai collecting or processing, or else you’re just another Pākehā guy who comes and holidays. So Croc spent a couple of years growing taro and selling it at the market, and making sure good taro was given to the elders.

I don’t think there’s any kind of formula or any set of arguments that could resolve Croc’s place in the whakapapa of tā moko artists. But being humble enough to take on local people’s ways of doing things is really important, and Croc loved that. Spending some time with him, tuned into him being on that frequency, part of me came to terms with it. There was understanding on a nonverbal level.

Another side was seeing who Croc was within the context of a Rarotongan community and the Pacific arts community that I respect. I came to understand that Croc had gone through the right processes to end up where he was—in this really, really rare situation of holding sacred tools as an outsider and occupying sacred space.

How his teacher, Inia, came to teach Croc is harder to understand. Inia saw something in Croc before it had even fully matured. The two had a special connection, but some would say Inia’s decision to teach the craft to a Pākehā outsider was crazy. He went totally against the grain of how Māoridom would think when he invited Croc to live with him and learn from him. Perhaps even Croc didn’t realise the full extent of what it means to take on the tradition, because after he got a couple of years in, he went over to Bali and wrote Inia a big letter about his uncertainties. He felt that the weight of responsibility was too big.

I don’t think there’s any kind of formula or any set of arguments that could resolve Croc’s place in the whakapapa of tā moko artists.

Ultimately, that kind of reflection is a good thing. It’s important to approach learning that way because it’s easy to love the idea of something. Croc had all the freedom in the world beforehand, then all of a sudden, he had proper responsibilities. There’s a moment when you have to decide that this is your craft, and this is your life. But to take on a tradition on the opposite side of the world, without the support of family? That’s something else.

***

After three or fourth months, it was time to go home. Croc and Ani mentioned that there was a waka sailing off next week that needed some crew, and that perhaps I could join it. As someone with terrible seasickness, I did my best to talk my way out of it. But Croc pointed out that if I was reviving the art form, I shouldn’t be flying the tools home on a plane. They should be sailed back to my island, the way they would have arrived.

The seasickness pills didn’t do anything. Neither did those acupressure things. I spewed about eight times a day, and thought I was going to be helicoptered off. I was going to be the embarrassment of the whole crew and the whole revival of the art form: ‘He’s the guy that got flown off the waka by a helicopter.’ That kept me focused. It was one of the most challenging things I’ve ever done. I had four days to prepare to face one of my biggest fears—being in the middle of the ocean and getting stuck out there.

I had four days to prepare to face one of my biggest fears—being in the middle of the ocean and getting stuck out there.

Of course, the weather was bad. It was meant to be a ten-day journey, but we took twenty-one. Our first little blip was running out of wind. And then we just sat down from Niue in the middle for five days, turning round in circles. The next blip was a big storm which blew us into Tonga, and one of the crew got hurt. We had to sail into Tonga so he could go to hospital, and someone else to the dentist. We had a couple of days there before the wind swung around. Then we just gunned it from Tonga and raced down to Auckland. It was magic to be out under the stars, in the middle of the moana, and to know that the tools were in the front of the bow.

The waka crew have been doing a parallel revival. They have Marumaru Atua and a couple of small waka sitting in the lagoon there in Rarotonga. It’s picturesque—looking at the lagoon and seeing these waka floating out. They live sailing, they live waka. They’re out there on the moana, stitching the hole in the sail, they’ve got all the routines, they know their chants, and they know their songs, and they know the names of the stars. Their level of commitment to their form was a beautiful ‘setting of tone’ for me.

***

I came back to Auckland to see Inia, Croc’s teacher. He offered for me to live with him and continue the learning at a little studio out West where he does his moko from. I lived in the storage room for a while like Harry Potter, helping with email in the morning, drawing, hanging out, cleaning up at the end of day and having dinner together. We’d debrief and talk about things, before I’d go clean his tools.

Photo supplied by Mokonui-a-rangi Smith

When I was with Inia, I would go back to Rarotonga every two or three months. Croc and I started doing my calf and continued the learning, because after doing some jobs at Inia’s, I had new questions. That was the process: Things would be revealed over time as things became relevant over time.

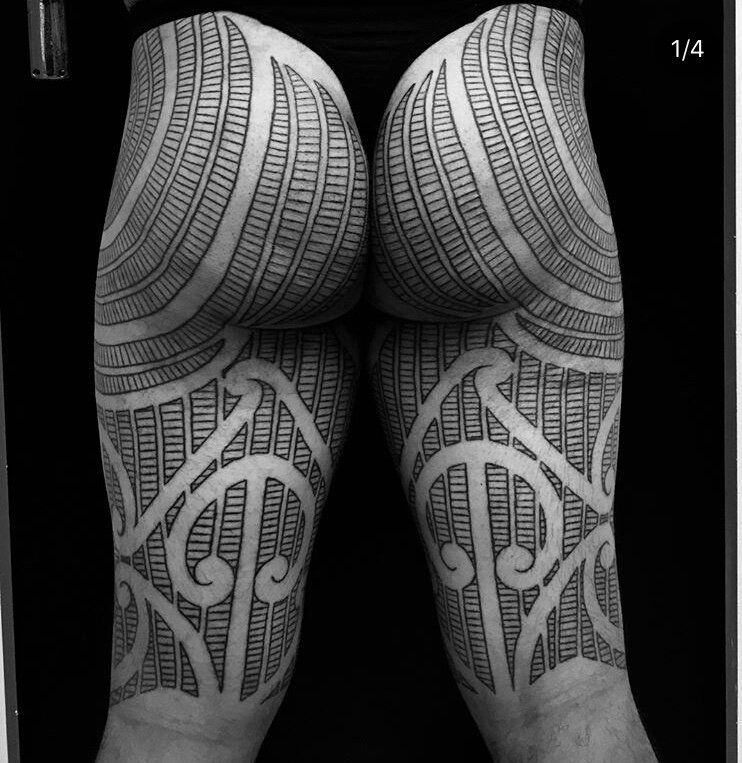

After about a year and a half, I said to Croc that I’d like to get my puhoro. We talked a lot about it, to help ground me within the practice, and help revive a taonga which has not been made with old tools for one hundredsomething years. We began designing it, tapping it.

The reason I kept flying back and forth was that legally, Croc couldn’t come to New Zealand. His terminal illness meant he was barred from entry, even though he was married to a Rarotongan New Zealander and had lived here before. Inia was pushing lawyers to represent Croc and get him back in, and after about three years, there was a law change. Soon, he was coming back for his medical treatment.

At the same time, we finished my puhoro and the apprenticeship process was coming to its end. When the puhoro was complete, we had a ceremony. It marked a kind of handing over, and the responsibility to uphold tikanga for everything else that happens around this space of tā moko—welcoming whānau in, karakia, whaikōrero, waiata, celebrations…

From there on, instead of the focus being on learning, it was on sharing space. We came to a level where we both understood, and I wasn’t asking questions any-more. We were having a good time, helping each other out at Inia’s place.

When the puhoro was complete, we had a ceremony. It marked a kind of handing over, and the responsibility to uphold tikanga for everything else that happens around this space of tā moko.

After a while, the spiral of hospital treatments began. Croc became weaker and his energy lowered. He had a lung transplant. I knew it was going to happen, but I hoped there would be more time.

All of a sudden, it was clear that the final step of my learning would be to run his tangihanga. His wife was grieving. His best mate and teacher, Inia, was having a rough time and wasn’t on this planet. But I had a feeling of how to run it.

The tangihanga became an extension into the space we had created as we worked together. It was an amazing feeling, like a lesson that was never intended but was definitely a continuation of what he and I had set up. It was the final step in a slow revelation of what a teacher-student relationship could be.

***

The teacher holds a special place, like the guru, who is a human God to the student. You go beyond yourself for them. You can define yourself based on that relationship.

There’s like a whānau aspect to what Croc has given to me. But then there’s a whakapapa aspect of inheritance through him. Energetically, he lives on in me. There is an imprint: that I aspire to grow into what he was, in my own way. The lines on my back were the last tattoo he made.

Mokonui-a-rangi Smith at his studio Uhi Tapu, Corbans Estate Arts Centre, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, 2022. Photo by Emily Parr.

He never tattooed at my studio at Corban’s, but he would pull in on his motorbike, and come and watch us. He’d come and stretch sometimes, when I needed a hand, or he’d come and hang out, and just sit there, talking to the clients while we worked. He was so proud, so happy to just see it alive. There was a sense of closure and context to his life. And I am sure that made the path easier.

***

There have been other kinds of unexpected relationships that have emerged. My partner Raukura Turei and I met for who we are. And then it was revealed that her mum, Jane Cooper, helped write and translate an important Tahitian tatau book back in the ’80s. And her dad, Pita Turei, helped write a tā moko book from the ’90s to the 2000s. It turns out they’re both old mates of Inia’s and used to live up the street. They’ve both built each other’s houses, borrowing the same hammer.

I’ve kind of landed in the middle of it. It’s been awesome for just grounding my mahi within a community who gets it, because Pita is part of the whakapapa as well, in terms of being a recipient and a supporter. Inia did his first piece on Pita.

These days, I have been doing my own research, working on Pita, doing the same lines on his back but with no stretchers and no pillow. I’m always trying to just focus on some aspect of the practice, and during the lockdown, I revisited old questions of mine which I’d shelved while learning under Croc and Inia. How come we normally use pillows? I’m sure none of our old Māori paintings and references have a stretcher. I couldn’t have attempted that kind of experimentation in the early days—it would have just been waving a tool around in the dark. Now I feel more tuned in.

I think something is going to evolve.

We’re experimenting with making the practice and the process lighter. It’s hard to tell whether that means the designs will adapt over time—maybe in a few years, we’ll find out. I think we’ll find that some parts of the body require a certain angle for the design to be on, and other parts of the body will have to be avoided, or we can only tattoo them in a certain way. And perhaps through that, we’ll come to understand why our ancestors had certain forms as a cultural practice. Already with our tools, there are spots where it doesn’t work well and you’re pushing a rock uphill. But after following this path enough, it might influence a style. I think something is going to evolve.

And Pita is super trusting, excited by it, not attached to the end result. Like with Inia, he knows that something good is going to come out of it—if not now, then later. That’s been an awesome support. He comes in here every day and says hi to us, and to the clients. Half the time he knows them. Sometimes he comes to do the morning karakia for us. There is a really beautiful interweaving of different strands of the community in Raukura’s whānau. You don’t plan those things.