Ka Pū Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Māori Identities in the Twenty-first Century

In this excerpt from 'Ka Pū Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Māori Identities in the Twenty-first Century,' leading social scientists Tahu Kukutai and Melinda Webber look at modern Māori identities.

In this excerpt from 'Ka Pū Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Māori Identities in the Twenty-first Century,' leading social scientists Tahu Kukutai and Melinda Webber look at modern Māori identities.

Waitangi Day: a national day of celebration, protest and self-reflection since annual commemorations began in 1947. It's a day that reminds New Zealanders of our history, and our complex and changing identity. On this Waitangi Day, we bring you an excerpt from 'Ka Pū Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi Māori Identities in the Twenty-first Century,' a chapter from the forthcoming book, Land of Milk and Honey? Making Sense of Aotearoa New Zealand. The introductory text for sociology students, and also for a general audience, calls on some of the country’s leading social scientists to help make sense of contemporary New Zealand.

Two of those social scientists are Tahu Kukutai (Waikato-Maniapoto, Te Aupōuri) and Melinda Webber (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāpuhi). Books Editor Sarah Jane Barnett had a quick chat with them about the chapter.

Sarah Jane Barnett: This is a fascinating piece of research with information I hadn't come across before. I was wondering, how do you hope to see your research used? Why was this research important to you?

Melinda Webber: Our chapter was designed to emphasise the complexity of Maori identities – they are simultaneously ever changing (because they are necessarily responsive to context, people, space, time) and sure and still (because our reo, tikanga, kawa and connectedness to our whenua, iwi and hapu will forever be the essence of what it means to be Maori).

Funnily enough these two things sound incongruous – but they are not. They ebb and flow, like the tides, and then they settle again. That is why the whakatauki in the title is so relevant because once one identity is worn and/or cast aside, a new one replaces it, naturally. Identities are like that – never fixed, always situational, necessarily fluid.

Tahu Kukutai: I would also add that these are also stories of agency and resistance. Agency is evident in terms of how we continue to identify ourselves in diverse ways; there's no cookie cutter recipe for what it means to be Maori in the 21st century (if there ever was!).

There's also shades of resistance in how we identify. Take the census. The vast majority of those who identify solely as Maori will have Pakeha whakapapa, sometimes a parent. I have a white Australian mother of Scottish descent but identify solely as Maori in the census. Why? Because that part of my whakapapa is irrelevant to my cultural identity. I'm Maori. And proudly so. When I was a kid the census required us to quantify our identities in blood fractions - a colonial hangover that lasted to the 1980s. These designations of identity were never inconsequential - politically, economically, socially, emotionally. As indigenous peoples its important that we define our identities, individually and collectively, as we see fit.

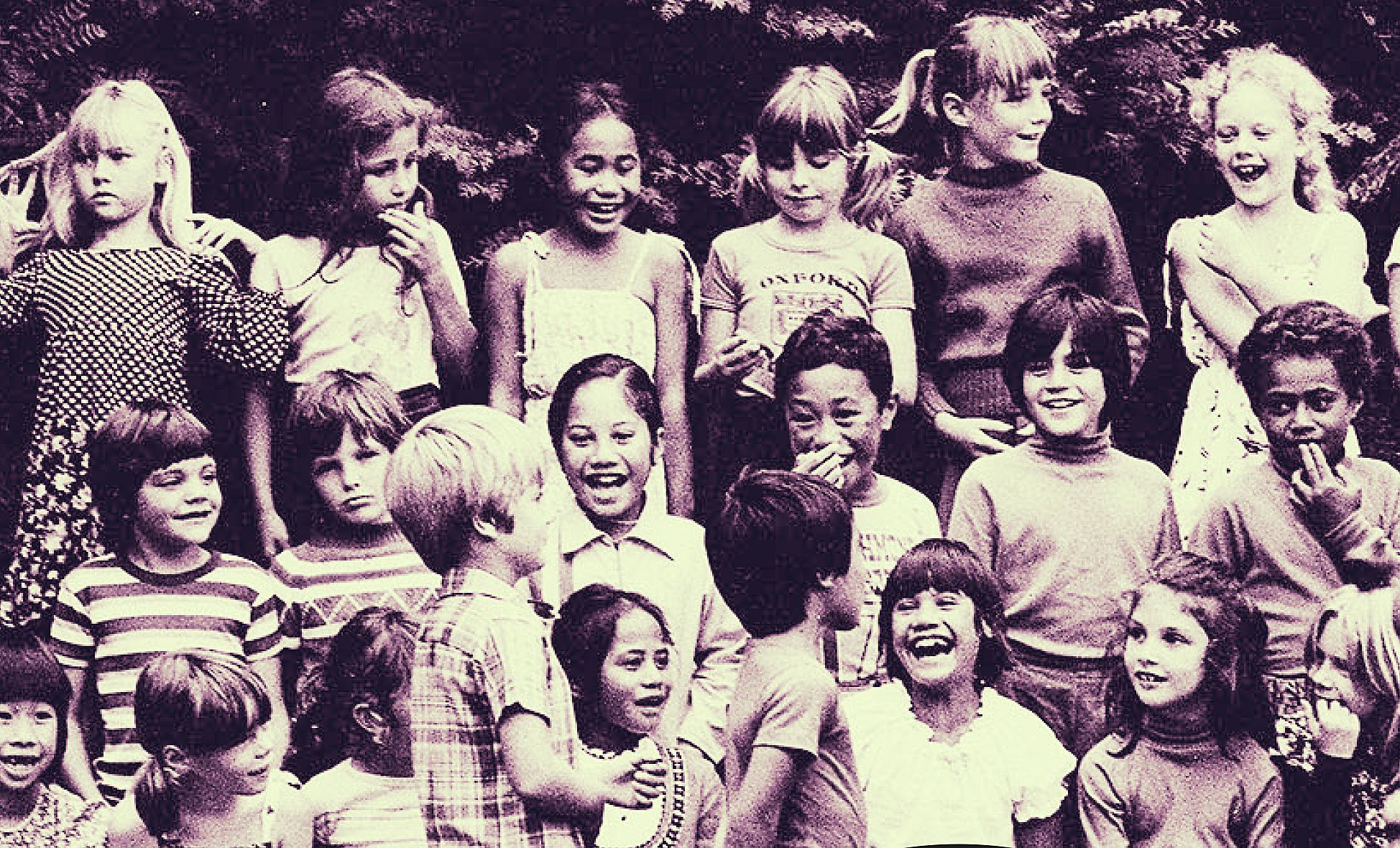

Māori identities in the twenty-first century continue to evolve while retaining vital links with the past. Like indigenous peoples in the colonial settler states of North America and Australia, Māori have shown remarkable resilience in maintaining a distinctive culture and identity in the face of coercive pressures to assimilate. The majority of Māori retain a sense of connection to ancestral iwi and marae, engage in some form of contemporary cultural practice, and see Māori culture as important (Statistics New Zealand 2013a). Māori comprise about 15 per cent of the total population of Aotearoa New Zealand and in some geographical areas the Māori share is as high as half. At the same time, the experience of ongoing forms of colonialism, coupled with demographic transformations and technological innovation, has produced a great deal of cultural and socio-econo diversity within Te Ao Māori (Māori society). This chapter offers a nuanced portrait of the ways Māori peoples adopt diverse cultural expressions to identify themselves, claiming deep connections to elements of traditional Māori identity whilst constantly renewing and reshaping what it means to be Māori in the twenty-first century.

To explore the themes of continuity and change in relation to contemporary Māori identities we draw on the fields of demography, sociology and social psychology. In so doing, we focus on two key contexts where Māori identities are articulated: the national population census and schools. We begin by exploring the dual nature of the census as a site where subjective Māori identities are created and expressed, and where ‘objective’ data about Māori are collected for the purposes of policy and planning. While Māori experiences with census-taking have at times been fraught, we argue that such data can nevertheless enrich our understanding of collective Māori identities and circumstances (Kukutai 2012).

In the second half of this chapter we consider how schools shape the ways Māori students construct their identities. Schools have long been recognised as a site where students receive and begin to understand messages from society about the value of their ethnic identity. Schools are therefore contexts where we make each other ‘ethnic’. Not only are schools central places for forming ethnic identities, but the ways in which teachers and students talk, interact and act in school influences the ways Māori students value and enact their Māori identities in the school context. Furthermore, schools are sites where Māori continue to be subjected to negative expectations that have profound implications for their academic performance (Rubie-Davies, Hattie and Hamilton 2006; Webber 2011).

[E]thnic identity has been found to be ‘consistently positively related to an individual’s self-esteem’ – a positive relationship implies that when a positive sense of ethnic identity increases, self-esteem also increases ... Since self-esteem is determined not only by individual attributes, but also by the collective attributes of the groups with which one identifies, an important question is how Māori cope when they belong to a social group – Māori – that is systemically negatively stereotyped.

Social psychology has always suggested that the social groups to which we belong, and the social identities to which we lay claim, help define who we are and thus constitute an essential part of the self (Tajfel 1981). Another fundamental assumption of social identity theory is that people strive to maintain or increase their self-esteem. Māori identity is one type of group identity that influences the self-concept and self-esteem of its members. Whilst Māori identity is only one of the many components that will comprise an individual’s sense of self, ethnic identity has been found to be ‘consistently positively related to an individual’s self-esteem’ – a positive relationship implies that when a positive sense of ethnic identity increases, self-esteem also increases (Umaña-Taylor 2004, 139). Since self-esteem is determined not only by individual attributes, but also by the collective attributes of the groups with which one identifies, an important question is how Māori cope when they belong to a social group – Māori – that is systemically negatively stereotyped (Mackie and Smith 1998). These socio-emotional aspects of identity development have a significant impact on whether Māori claim, or reject, Māori identity.

Māori Identities in the National Population Census

The five-yearly Census of Population and Dwellings remains the key source of official data about Māori. Such data are used for a wide range of purposes, from determining electoral boundaries and population-based funding in social spending, to informing policies to enhance Māori cultural and linguistic vitality. Despite appeals to the objective and scientific nature of the census, the context and motivations underpinning census- taking have always been tied to the exercise of power. For indigenous peoples worldwide, the census has often served as an instrument of state control and reflected ideas about racial difference that were (and sometimes still are) used to justify European domination (Anderson 1991). In Aotearoa New Zealand, the interest in counting Māori-European ‘halfcastes’ in the 1800s and early 1900s was clearly linked to colonial policies of racial amalgamation and government efforts to limit the boundaries of Māori identity and entitlement (Kukutai 2012). Nowadays, the census tends to be seen as a site for group empowerment and recognition rather than control, and receives broad support from iwi and Māori organisations and communities.

Aotearoa New Zealand is one of a small number of countries around the world that asks multiple identity questions in the census. Since 1991 it has been possible to identify as Māori on the basis of ancestry, ethnicity and iwi (tribe). Each of these is conceptually distinct and yields populations that differ in size and composition. As Table 1 shows, the largest and most inclusive grouping is the Māori descent population (ancestry basis).

Table 1: Parameters of Māori identity (Statistics New Zealand 2013a).

Māori descent 668,724

Māori ethnic group 598,602

Iwi affiliated 545,941

In 2013 the question read: ‘Are you descended from a Māori (that is, did you have a Māori birth parent, grandparent or great-grandparent, etc)?’ Nearly 669,000 individuals ticked the Māori descent box. The number identifying as Māori on the basis of ethnicity – meant as a measure of cultural belonging rather than ancestral heritage – was substantially lower at just under 600,000. Most of the remaining 69,000 Māori descendants identified solely as ‘New Zealand European’ (in 2013 there was no ‘Pākehā’ tick-box). That a sizeable number of New Zealanders acknowledge their Māori ancestry but do not feel Māori in a cultural sense may reflect their level of comfort and familiarity with Te Ao Māori in terms of family upbringing and networks, as well as personal choice.

Turning to iwi, just under 536,000 individuals reported at least one iwi affiliation in the 2013 census, representing 83 per cent of the wider Māori descent group (Statistics New Zealand 2013a). This share is surprisingly high when we consider that most Māori live outside of their tribal rohe (boundaries). The migration of Māori from rural heartlands to towns and cities after World War II dramatically changed the Māori social structure. A classic study of urban Māori migrants in the 1950s observed that, for many, ‘the tribe was largely an abstract concept’ (Metge 1964). The revitalisation of iwi identity, a process that began in the 1970s, reflects a number of factors including Treaty settlement processes which have raised both the public profile of iwi and the incentives for individuals to affiliate, along with shifts in the broader socio-political environment. A significant driver of iwi population growth in the census is the addition of ‘new’ affiliates who have discovered or reconnected with their whakapapa (genealogy) (Kukutai and Rarere 2013). Waikato and Ngāi Tahu (Kāi Tahu) are instructive examples. Between 1991 and 2013 each iwi increased by 80 and 170 per cent respectively. This growth far exceeds what can be explained by natural increase alone (i.e., more births than deaths). Little is known about whether these patterns of identification carry over into membership registers maintained by iwi themselves. While the census relies entirely on self-report, iwi registers typically require some form of social recognition – such as endorsement by a kaumātua (elder) – and specific details of a whakapapa connection to marae or hapū (sub-tribe). In such contexts, self-identification alone is insufficient to be recognised as an iwi member. Interestingly, in the census, Māori women were more likely than men to identify with an iwi, particularly in middle age (Kukutai and Rarere 2013). Women were also more likely to report having knowledge of their ancestral connections to hapū, awa (river), maunga (mountain) and tupuna (ancestors) (44 per cent of Māori women knew all these, compared to 37 per cent of Māori men) (Statistics New Zealand 2013a).

While most Māori are counted in all three census groupings shown in Table 1, there are stark differences between those who have multiple expressive ties to Te Ao Māori, and those whose only connection is through ancestry (Kukutai 2010). The former are much more likely to speak te reo Māori, to live in areas with a high Māori population share, to be partnered with a Māori and to have a lower socio-economic status. The reasons for this are complex but reflect, among other things, long-standing ethnic inequalities, differences in access to Māori culture and networks, and changes in the ‘costs’ associated with being Māori.

Emerging Māori Identities

In contemporary Aotearoa, Māori students experience diverse realities and their ethnic identities take various forms in response to the contexts within which they are shaped (Durie 2005). Drawing on Penetito (2011, 29), we assert that ‘there are multiple ways of being Māori’, none of which are more tuturu (authentic) than the other. Research has shown that the ethnic identities of Māori students can be positively influenced by acquiring and/or maintaining a sense of connection to iwi, hapū and marae, and by engaging in various Māori cultural practices (Hollis 2013; Rata 2012). Nevertheless, there are many Māori who continue to feel disengaged from Māori culture, and as Penetito (2011, 44) has noted, many Māori in this category ‘don’t know how to join in or how to belong’. Penetito has also stated that disengaged Māori differ in their willingness and ability to access Māori culture, noting that ‘they do not know what that is, where to get it if they want it, or even whether it is something worth wanting’ (29). For those people of Māori descent who do not consider themselves to be culturally distinct from non-Māori, the social category ‘Māori’ may not hold much personal significance (Rata 2012). Similarly, there are Māori who consider themselves more affiliated to their iwi or hapū rather than the pan-Māori label. What is clear is that Māori have a plethora of identity options available to them.

For most, if not all of us, our socialisation as racial-ethnic-cultural beings begins early in life within our whānau (family), and much of this socialisation continues during the compulsory years of schooling, from preschool to secondary school, and even further during post-compulsory education, should a person go, and beyond. Māori identity therefore emerges in institutional, cultural and familial contexts; it is neither static nor one-dimensional...

For most, if not all of us, our socialisation as racial-ethnic-cultural beings begins early in life within our whānau (family), and much of this socialisation continues during the compulsory years of schooling, from preschool to secondary school, and even further during post-compulsory education, should a person go, and beyond. Māori identity therefore emerges in institutional, cultural and familial contexts; it is neither static nor one-dimensional; and its meanings, as expressed in schools, neighbourhoods, peer groups and whānau, vary across time, space and place. Our focus here is: how and why Māori identity matters to Māori adolescents; and what factors and perceived associated cultural behaviours may impact on their commitment to this ethnic label.

The Components of Māori Identity

Māori identity, in its broadest sense, comprises three key components – race, ethnicity and culture. The three components interact together to give Māori adolescents a sense of individual and collective identity. The first component is race; we cannot avoid the fact that socially constructed perceptions of race, and consequently racism, are an everyday occurrence for many Māori adolescents. Notions of race essentialise and stereotype Māori, their social statuses, their social behaviours and their social ranking. In the form of racism, race continues to play an important role in determining how Māori adolescents construe, indeed construct, their Māori identity (Webber 2012).

The second component is ethnicity, which is most closely associated with issues of belonging and membership. Ethnic boundaries operate to determine who is a member, and who is not, by the use of criteria such as language, knowledge of descent, participation in cultural activities and the like (for further discussion of what is meant by ethnicity, see Matthewman in this volume). Therefore, Māori identity is largely dependent on adolescents developing knowledge, and eventual mastery of, component three – culture. Culture dictates the appropriate and inappropriate content of a particular ethnicity; typically knowledge of the language, religion, belief system, art, music, dress and traditions of an ethnic group is designated as the basis of membership in that ethnic group. These elements of culture are part of a ‘toolkit’, as Swidler (1986) called it, used to create the meaning and way of life seen to be unique to particular ethnic groups. Thus, culture can be seen as the substance of ethnicity and the mechanism by which adolescents might ‘demonstrate’ their authenticity as group members.

Positive Māori Identity Development

Developing a positive and strong Māori identity can be complex. Primarily, Māori identity is negotiated, defined and produced through an adolescent’s social interactions with others, most importantly their whānau and peers. It is within these interactions that they learn about culture – the behaviours, languages, stories and customs associated with ‘being Māori’. However, Māori identity is also influenced by external racial, social, economic and political messages that shape and inform certain identity choices. These components influence the construction of Māori identity, and the meanings Māori adolescents attach to it.

There are a number of key influences on the ways Māori adolescents construct Māori identities (Hollis 2013; Rata 2012; Webber 2011, 2012). The first is their sense of connectedness and belonging to the Māori label. Māori adolescents, across a range of studies, have consistently asserted that Māori identity is associated with knowing what ‘being Māori’ means, knowing where they come from and knowing what connects them to others as Māori. Hollis’s (2013) model of positive Māori youth development identified relationships, involvement in cultural activities, cultural factors (including access to environments to learn about culture and respecting and valuing culture), education/work, health/healthy lifestyles, socio-historical factors (including history, social attitudes towards Māori and Māori youth, community and media) and personal characteristics (such as resilience and having goals/aspirations) as factors contributing towards positive Māori identity development. Hollis’s research also argued that key indicators of positive Māori identity development included:

- Collective responsibility: Māori adolescents contributing towards the collective (whānau, community and society) and acknowledging their place amongst these groups.

- Successfully navigating the world: Māori adolescents navigating Māori and non-Māori environments with confidence.

- Cultural efficacy: knowing te reo Māori and tikanga (Māori protocols and traditions); being proud of being Māori and wanting to share that with others.

- Health: Māori students attending to their physical, emotional and intellectual health.

- Personal strengths: individual qualities including confidence, achieving desired goals, personal responsibility and curiosity. (104–5)

Māori adolescents also construct a positive sense of connectedness to their identity as Māori through socialisation messages from their whānau and peers (Webber 2011) and participation in Māori cultural activities (Rata 2012). Arama Rata’s (2012) research showed that a school’s cultural environment can enhance or constrain Māori identification, which in turn can increase or decrease psychological well-being and engagement in learning. Overall, Rata’s results suggested that any school interventions designed to increase Māori adolescents’ cultural engagement could consequently enhance their Māori identity, which could then increase their well-being. Māori adolescents who are ‘well’ are more likely to feel confident in their ability to learn because ‘when adolescents . . . develop healthy, positive, and strong racial identities . . . they are freer to focus on the need to achieve’ (Ford, Grantham and Moore 2006, 16).

Whānau also play a crucial role in helping Māori adolescents to learn about who they are, and who they are not, by means of socialisation into the cultural aspects of their Māori identity. This form of ‘cultural socialisation’ can be evidenced in parental practices, including teaching them about their Māori heritage and histories; promoting cultural customs and traditions; and promoting cultural, racial and ethnic pride, either deliberately or implicitly (Webber 2011). Whānau practices like these are likely to promote racial-ethnic pride in Māori adolescents and prepare them to succeed in both their Māori and non-Māori endeavours.

[T]he most resilient and tenacious Māori adolescents are those who have a well-developed awareness of the role that racism and discrimination could play in their lives. There is clear evidence that having a strong, positive sense of Māori identity may protect Māori adolescents from the negative social and academic impacts of perceived racial-ethnic group barriers or of experiencing interpersonal discrimination and racism based on their ethnic group membership.

Māori adolescents with salient Māori identity, positive attitudes towards their ethnic group and an awareness of racism are more likely to have the resilience to deal with adversity in the form of racist experiences (Webber 2011). Additionally, the most resilient and tenacious Māori adolescents are those who have a well-developed awareness of the role that racism and discrimination could play in their lives. There is clear evidence that having a strong, positive sense of Māori identity may protect Māori adolescents from the negative social and academic impacts of perceived racial-ethnic group barriers or of experiencing interpersonal discrimination and racism based on their ethnic group membership (Webber 2011, 2012).

Conclusion

‘Ka pū te ruha, ka hao te rangatahi’ is a well-known Māori proverb which literally means ‘Once the old fishing net is worn, it is put aside to make way for the new fishing net’. In the case of this chapter, the old net represents what Māori identity may have signified in the past, while the new net represents the changing and situational nature of Māori identity for younger generations. It refers to the constant remaking of Māori identities to better suit changing contexts, communities and collective needs.

Māori identity in the twenty-first century is a slippery concept. Like other collective or social identities, Māori identity is an overarching category that subsumes others within it. As diverse Māori identities have emerged, a new range of identity expressions – or at least more elastic meanings for old identity expressions – have been required. In examining the parameters of Māori identity, it is clear that there is no absolute, definitive meaning regarding what it means to be Māori. However, the enduring thread that continues to bind Māori together is the ongoing relevance of whakapapa, and a commitment to protecting the collective right to build and maintain salient Māori identities. Who and what constitutes someone as Māori will always be a contested question. Māori peoples in twenty-first-century colonial contexts continue to face many challenges, not least of which is the struggle to retain a distinct identity, beliefs, knowledge and cultural traditions.

Note: This excerpt has been edited for length with a section titled 'Multiple Ethnic Identification' appearing in the original; Full references for in-text citations are available as a PDF.

Tahu Kukutai (Waikato-Maniapoto, Te Aupōuri) is an Associate Professor at the Institute of Demographic and Economic Analysis, University of Waikato. She specialises in Māori and indigenous demographic research and has an ongoing interest in how governments around the world count and classify populations by ethnic-racial and citizenship criteria. In a former life she was a journalist.

Melinda Webber (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāpuhi) is Senior Lecturer and Associate Dean in the Faculty of Education at the University of Auckland. Melinda's research examines the ways race, ethnicity, culture and identity impact the lives of young people - particularly Māori students.

This chapter appears in A Land of Milk and Honey? Making sense of Aotearoa New Zealand, available from Auckland University Press.