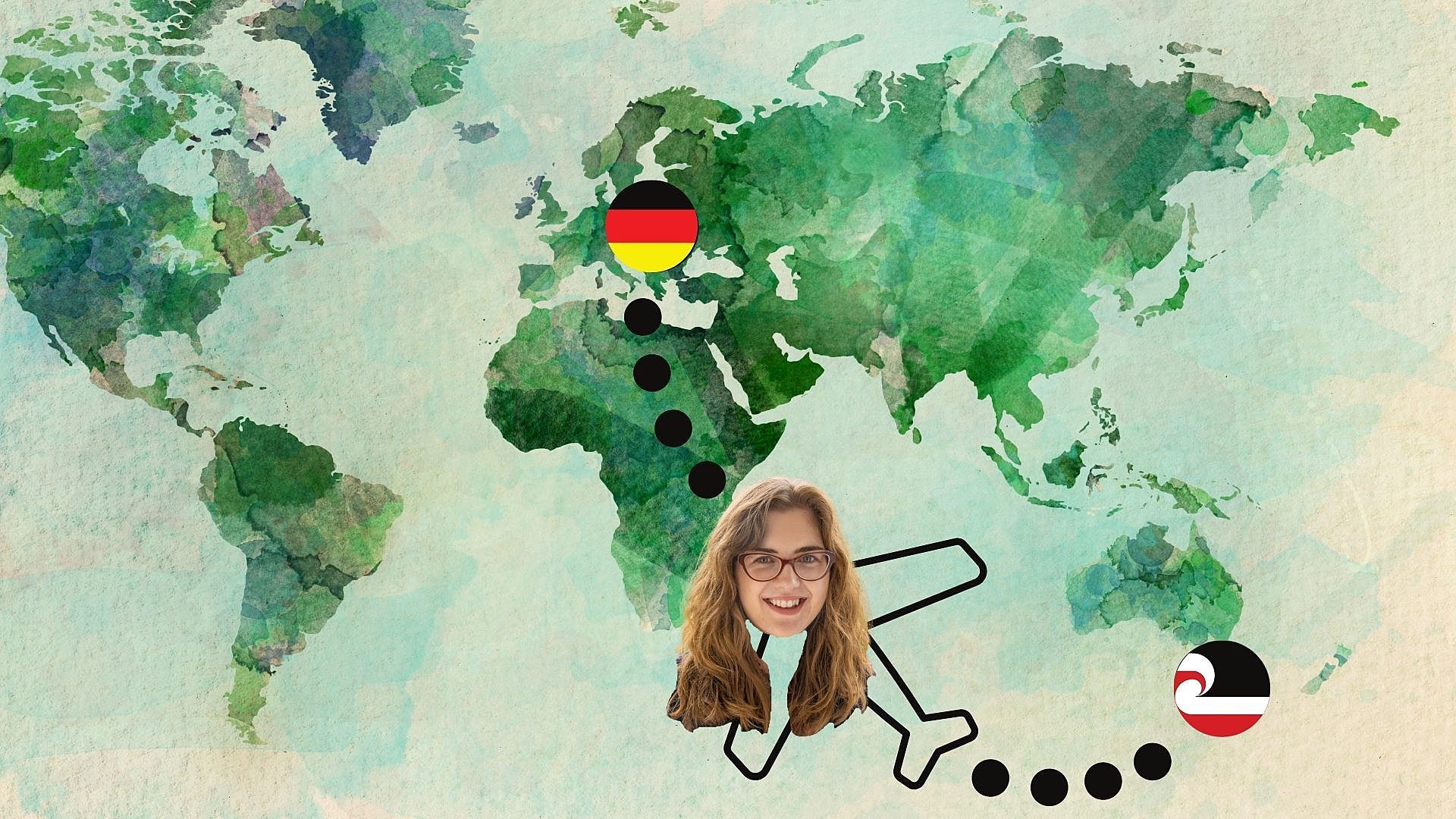

Māori Migrant

Vanessa Ellingham (Te Ātiawa, Taranaki, Ngā Ruahine) on finding her place in the Māori diaspora.

The first meeting of our waiata group is in a quintessential Berlin bar: it’s all wooden floors and vintage velvet couches; it stinks of smoke, and it’s run by Australians.

What we don’t know yet is that this will be our group’s only gathering – a couple of weeks later I’ll be asked to work from home (I’m still here, 20 months later). But on that icy February evening a handful of us Māori living here in Berlin, plus one New Zealand Embassy worker and a British guy, huddle together over photocopied lyrics of waiata Māori and do our best. It feels to me like the start of a new chapter in my Berlin life, one I wouldn’t have even known to dream about.

After karakia whakamutunga, I stand with Ashley and Tu on the corner of Sonnenallee, a street synonymous with shawarma shops, Syrian sweet stores and souped-up cars. We pause to say goodbye, despite the Siberian wind whipping up the street. Ashley’s drawn an illustration of a wahine with flowy black locks, surrounded by the whakataukī: E kore au e ngaro, he kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea, I shall never be lost, for I am a seed sown from Rangiātea.

A wahine surrounded by the whakataukī: E kore au e ngaro, he kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea

The pads of my fingers stick to the underside of the silky white paper as I cradle it on the clammy underground train home, trying to keep my new taonga flat. He kākano, a seed, forever connected by whakapapa, dispersed by the prevailing conditions.

This isn’t the first time Ashley has delivered me exactly what I’ve needed. The previous year, during the occupation at Ihumātao, I watched Instagram lives of thousands of kaitiaki protecting the whenua through long freezing nights, invoking the passive resistance of my own Parihaka ancestors. From half a world away, I saw a woman in a tight skirt suit kneel down in the frosty grass and dig and a boy of no more than ten walk up to a police officer and stick his little arms out. What was I still doing here?

Two days later, I got a Facebook notification to say someone named Ashley had created a meet-up for Māori in Berlin to discuss Ihumātao and how we could tautoko from afar.

Illustration by Ashley Clark.

We bonded over a Tayi Tibble essay about her experience showing up at Ihumātao

Passing for white has plenty of advantages in a world still riddled with white supremacy, but it has often meant feeling like I’m playing catch-up in te ao Māori. I prepared myself to do the same with this new crew, but no need – something about us all being so far away from home meant that we gelled instantly. Five wāhine Māori enjoying some kai, ranting about politics and giggling as if we’d known each other for years.

We bonded over a Tayi Tibble essay some of us had read earlier that morning about her experience showing up at Ihumātao. “[L]ike ‘feel the fear and do it anyway’”, she wrote, “I ‘felt the whakamā and got out of the fucking car’ anyway.” Before I knew it, we were talking about feeling whakamā like it was everyone’s business. My anguish about not being home for important kaupapa wasn’t just mine, it was something many of us carry.

Of course, I wasn’t the only Māori kicking around Europe. And I was hardly the first Māori to go on a haerenga, either. That’s kind of our thing! But some pretty poor New Zealand history education, combined with a lack of community, had left me disconnected from that part of myself, feeling like I was doing it all wrong. I’d already grown up outside te ao Māori. Only a bad Māori would move even further away, I’d thought. Thankfully, joining the Māori in Berlin group, combined with a lot of reading, has helped right my waka. As Talia Marshall observes, for many Māori living away from home, our “way of being at home consists of talking about it.”

Only a bad Māori would move even further away, I’d thought

For anyone else who wasn’t taught in school: our tīpuna were among the world’s most legendary voyagers. Their navigation skills enabled them to traverse Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa and reach Aotearoa about 400 years before Pākehā ever ‘discovered’ our lands. Four thousand years ago, when they set out from Taiwan to populate the Pacific, they already had the skills to begin exploring our moana. Contrary to what I learnt in school, (that they drifted to Aotearoa by accident), our tīpuna absolutely knew what they were doing.

But migration didn’t stop once they reached Aotearoa. There was plenty of movement across and between our islands. Speaking with Te Poihi Campbell, Pouwhakakori at Te Kotahitanga o Te Ātiawa, I learnt that my own people were often on hekenga, especially in the first half of the 1800s. Each heke had a purpose, sometimes fleeing warfare or establishing ourselves in new areas, ideally ones where we could reaffirm whakapapa connections.

Ngāpuhi poet Robert Sullivan has described Māori as being “of waka memory”1; our migration history is embedded in our DNA. European arrival offered opportunities for Māori to see parts of the world outside Te Moana-nui a Kiwa, invoking that waka memory once again. Some Māori joined voyages to other parts of Polynesia not seen by our people for centuries, while others set out to sate their curiosity or build relationships further afield. Some paid their passage by contributing their coveted seafaring skills and knowledge of the moana.

Ngāpuhi poet Robert Sullivan has described Māori as being “of waka memory”; our migration history embedded in our DNA

There was a lot of interest in meeting the Queen of England, or the King, depending on the period. Ngāpuhi rangatira Hongi Hika met King George in England in 1820 and also spent time at Cambridge writing a Māori–English dictionary.2

In 1824, Ngāti Toa ariki Te Pēhi Kupe jumped aboard a brig headed to England, hoping to procure weapons to avenge his children.3 When the captain fell into the sea, Te Pēhi dived in and saved him, resulting in a close friendship that may have inspired Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

Nineteenth-century Māori on the move did not limit themselves to seeing the English-speaking world. In 1860, Ngāti Maniapoto chief Hemara Te Rerehau and Wiremu Toetoe Tumohe (Ngāti Apakura and Ngāti Wakohike) spent time in Vienna, where they were invited to so many social gatherings that they soon had to get a diary to keep track of them all.4 After they learnt about the printing process during their visit, Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph gifted them a press that was sent to Aotearoa and used to print the first pro-Kīngitanga newspaper.

It's easier to see my own journey as one more link in a more than 200-year whakapapa of Māori voyages to Europe

The fourth Māori King Te Rata continuing a Kingitanga tradition of diplomatic relations with Britain, one that Nanaia Mahuta continues today.

Māori King Tāwhiao’s 1884 diplomatic visit to England is recounted in Roger Blackley’s paper, King Tāwhiao's Big O. E.Framed like that, it’s much easier to see my own journey here not as an anomaly, but as just one more link in a more than 200-year whakapapa of Māori voyages to Europe.

Tāwhiao and his touring party had “a sympathetic hearing in the British press and among the public”, according to O’Malley. Journalists explained the devastation of Waikato land confiscations to their readers and even included tips on how to pronounce Tāwhiao’s name correctly.5 However, the group was ultimately not permitted to meet the Queen, as the British government sought to wipe its hands of ongoing tension in New Zealand.

Not everyone who ventured out came home. Whakarewarewa performer Mākereti Papakura married an Oxfordshire landowner in 1912 after touring England, dedicating one room of her manor to all her taonga Māori. She then opened her homes to Māori soldiers during World War 1, another group of Māori on the move, some of whose descendants still take the names of the Italian towns where their tīpuna served, generations later.

I’m steadied by the knowledge that I’m walking in the footsteps of many Māori before me

Despite the expectations of British missionary hosts eager to assert their own beliefs, in Haerenga, O’Malley finds that early Māori travellers to Europe did so “selectively and on their own terms”,6 driven by their own curiosity and interest in forging diplomatic relationships.

I used to think I’d ended up over here because my education had taught me to pedestal everything European: the languages, the art, the history, the literature, all taking me further and further away from my Māori self. Now I’m steadied by the knowledge that I’m walking in the deliberate footsteps of many Māori before me.

**

Alice Te Punga Somerville’s Once Were Pacific: Māori Connections to Oceania opens with a description of a drawing you’ve probably seen before: an unnamed tāne Māori trading crayfish for cloth offered by British botanist Joseph Banks. All three figures, including the kōura, gesture with flat jazz hands. However, it’s not how they’re rendered but who drew them that’s important here: they were drawn by Tupaia, the Tahitian navigator who guided Cook to our shores. Tupaia’s home was Ra‘iatea, or Rangiātea in Māori, the same one referenced in Ashley’s gift that chilly night on Sonnenallee. Tupaia had arrived from “back home”.

We’ve been shifting home, calling home, invoking home and remembering home for a very, very long time

And the fateful trade he depicted was so much more nuanced than the simple moment of first contact that’s usually foregrounded in the image’s description. As much as it was the first meeting between two peoples, it was also a moment of recognition of the long-remembered migration of our tīpuna. The regular goods Europeans were expecting to hand over were “trumped by large sheets of tapa recently acquired in Tahiti.”7

The aute plant used to make tapa hadn’t thrived in Aotearoa, meaning our tīpuna were unable to produce the tapa their ancestors had brought with them from warmer climes. So when they saw the sailors had tapa on board, the large papery cloth they’d heard of but never seen themselves, they were elated. I’ve lived overseas for almost a decade and I still get teary when I find a parcel in the mail from my mum. So receiving that tapa and recognising it from hundreds of years earlier must have been the best migrant mail delivery of all time. We’ve been shifting home, calling home, invoking home and remembering home for a very, very long time.

Tupaia's drawing of that fateful trade.

I was beginning to have difficulties squaring my indigeneity with my migrant identity. How could I be both?

Here in Berlin, I run a magazine about migration called NANSEN. When we launched our first issue in 2017, a French newspaper correspondent interviewed me about the magazine. When she asked about my background, I attempted to explain that Māori are an Indigenous population that are both tangata whenua and a people with a migration history of our own.

Quotes are often edited or cut down for brevity, but by the time the article came out and I’d put it through Google Translate, it sounded like I was talking about Māori people as migrants in the same way as any other arrivals to Aotearoa. I felt sick.

I emailed the journalist and asked her to either add in the rest of my quote for more context, or cut the quote entirely. She chose to cut it and, looking back, I’m not surprised. Earlier that year, Disney’s Moana had deftly distilled the tension between rootedness and a yearning to explore, a duality that can be difficult for grown adults to get our heads around. I was beginning to have my own difficulties squaring my indigeneity with my migrant identity. How could I be both? The interview had been one more big plop in the bucket that said I was doing it all wrong.

I wondered if, by becoming a migrant, I’d cut myself off from being Māori altogether

Narratives about the failure of Māori who aren’t present on their whenua are pervasive and run deep. In the 1990s, being “urban Māori” was often equated with being “non-iwi”, explains Erin Keenan in her doctoral thesis on the topic.8

Some of the kaumātua Keenan interviewed for her thesis rejected the term “urban Māori” as they found it too colonising. It reinforced their perceived separation from their iwi and whenua, whether they saw themselves that way or not.9

Being pushed into ever-shrinking boxes has prevented many of us from being able to imagine who we might be capable of becoming – or who we might have been all along. How often do Māori living away from our tūrangawaewae end up defining ourselves by how much reo we do or don’t speak, how often we do or don’t show up at our marae? Until I met the Māori in Berlin crew, I wondered if, by becoming a migrant, I’d cut myself off from being Māori altogether.

What if I wasn’t lost, or dissenting, but representing?

For the second issue of NANSEN magazine, I interviewed Kalaf Epalanga. He’s a writer and musician best known as part of a band that fuses Angolan beats with European dance music, synthesising the group’s mixed roots.

Born in Angola shortly after its independence from Portuguese rule, Kalaf has lived in Europe for more than two decades. I asked him what it meant to be present in Europe, specifically in Portugal, the nation that colonised his own. He told me that his visibility as a successful black man in Portugal sent a strong message – that it might even be more important for him to be present in Europe than back in Angola. This flipped the way I’d seen myself as a Māori living in Europe. What if I wasn’t lost, or dissenting, but representing?

When I tell Germans I’m Māori they say, “you don’t look Māori”, as if that might be news to me

Of course, when I tell Germans that I’m Māori they almost always say, “you don’t look Māori”, as if that might be news to me. Still, I hope I might be able to offer a slightly more nuanced account of what it means to be Māori today: how some of us got disconnected, while others held on. How we’re reconnecting now.

That level of detail might be beyond the realm of small talk, but, still, I want to stand confident in my bothness, as a migrant and an Indigenous person.

I asked Te Poihi Campbell about this duality, and suddenly we were talking about another duality entirely. “We are Indigenous because we come directly from the lands, land features, waterways,” he told me. “Our whakapapa reflects this, our narratives reflect this, it’s just that these kōrero are not in the public arena. The waka kōrero is familiar and has become commonplace but Taranaki has a rich Indigenous kōrero that is just starting to emerge.”

He explained that our tīpuna are the Polynesians who arrived by waka, and also the Kāhui Maunga people who were present in Taranaki long before them. So, another set of tīpuna and another duality. Polynesian voyagers and Te Kāhui Maunga.

“Are you going to cry?” Siddhartha asked. “A Tongan lady came in here once and she cried”

“Whether one can be a migrant and Indigenous at the same time is particularly pressing in the context of a state that articulates itself as a nation of immigrants,” writes Te Punga Somerville.10 With a national narrative based on the common experience of immigration, we may have been led to justify our presence on those terms, hence the dominance of the “waka kōrero”. But we are Indigenous, too – to the moana and to our maunga.

**

When the shops finally reopened here after a lockdown that lasted all of Berlin’s five-month winter, the first place I visited was Hopscotch, a bookshop centring non-Western and diasporic perspectives. Suddenly surrounded by new books after far too long with my own thoughts and possessions, I asked the owner, Siddhartha, for some guidance. Did he have anything from the Pacific? To my delight, he handed me a book co-edited by Ruth Buchanan, a Berlin artist with Taranaki roots. That was enough for me, but then the very first page of her book I opened revealed a piece written by the artist WharehokaSmith, or, as I call him, Uncle Steve.

“Are you going to cry?” Siddhartha asked. “A Tongan lady came in here once and she cried.”

I emailed Uncle Steve to let him know what I’d found. Turns out I’d got a copy of the book before he’d even had a chance to send copies around to my mum and their other siblings, the ones not living half a world away. He wrote back, “our tīpuna are always looking after us.”

In the 1850s, Te Arawa writer Wiremu Maihi Te Rangikaheke wrote a letter that he hoped to send ‘home’ to Hawaiki

In the 1850s, Te Arawa writer Wiremu Maihi Te Rangikaheke wrote a letter that he hoped to send ‘home’ to our spiritual homeland Hawaiki, having recently met a man from elsewhere in the Pacific who was headed back in that direction.

He requested a shipment of food from Hawaiki, a request Te Punga Somerville interprets as a shipment of knowledge to sate his intellectual and spiritual hunger. “Like the Māori people at Uawa instantly recognising the tapa on Cook’s ship as a manifestation of a bigger picture beyond the here and now, Te Rangikaheke desired to engage in a visceral and personal way with ‘the place from which our ancestors came in former times.’”11

He wrote to “affirm tikanga and seek correction”.12 “Totally me!” I wrote in the margin, thinking of my email home to Te Poihi Campbell, asking if he could confirm what I thought I knew and correct what I didn’t. How I went in search of confirmation of our migrancy and received fresh reassurance of our indigeneity as well.

Morrison finds that Hawaiki might not be one specific physical place but something more elusive

Last year, I found a way to watch Scotty Morrison’s Television New Zealand show Origins from here in Germany. (Accessing TV from home has long been a common migrant struggle. Pre-internet, a migrant stereotype was a satellite dish attached to the roof or apartment balcony, but today we're more likely to use VPNs to overcome geo blocking.) In the show, Morrison seeks out Hawaiki in the various places our ancestors are known to have whakapapa connections: French Polynesia, the Cook Islands, Sāmoa, Vanuatu, Taiwan and even Ethiopia, where evidence of the first humans has been found. Many of his interviewees in Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa use the word “Hawaiki”, but each person he meets locates it in a different place.

Morrison finds that Hawaiki might not be one specific physical place but something more elusive. It might simply be the last place your ancestors left off from.

These days, my feet are still planted here in Berlin, but the nose of my vessel is pointed towards home

This idea is supported in historian Madi Williams’ new book, Polynesia 900–1600. As quoted from the book in E-Tangata, Ngāi Tahu elder Teone Taare Tikao explains that as our tīpuna sailed from island to island, they would name each new place Hawaiki in memory of their previous home.

We descend from Hawaiki, or multiple Hawaikis. And we descend from Rangiātea, our other spiritual home, also known as the first whare wānanga. When we talk about someone pursuing knowledge, we can refer to the whakataukī, Kia puta ai te ihu ki Rangiātea, so that your nose may reach Rangiātea.

I’d long had my head turned towards Europe and everything it has to offer. But the way to release a sore neck is to stretch it back in the other direction. These days, my feet are still planted here in Berlin, but the nose of my vessel is pointed towards home, and all the homes before it.

1 Robert Sullivan, “Waka 100,” in Star Waka (Auckland University Press, 1999).

2 Vincent O’Malley, Haerenga: Early Māori Journeys Across the Globe (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2015), 74–75.

3 Tamihana Te Rauparaha and Ross Calman, He Pukapuka Tātaku i Ngā Mahi a Te Rauparaha Nui (Auckland University Press, 2020), 35, 3–36, 7.

4 O’Malley, Haerenga, 112.

5 Ibid., 134.

6 Ibid., 141.

7 Alice Te Punga Somerville, Once Were Pacific: Māori Connections to Oceania (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), XVI.

8 Erin Keenan, “Māori Urban Migrations and Identities, ‘Ko Ngā Iwi Nuku Whenua’: A study of Urbanisation in the Wellington Region during the Twentieth Century” (PhD diss., Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka 2014), 35.

9 Ibid.

10 Te Punga Somerville, Once Were Pacific, 207.

11 Ibid., 196.

12 Ibid., 210.