Māori Legends – Aroha Mō Ngā Pukapuka

Aroha Novak on Te Reo Māori picture books, and the Aroha and Awhi you find there.

Growing up in the 1980s and 90s in Ōtepoti Dunedin, my first encounter with racism was when I was about six. My best friend’s sister wouldn’t sit beside me in the car because I was Māori. At that point in my life, I didn’t even know what Māori was, but figured out that I didn’t really want to be one if people were going to be mean to me.

From that moment, I tried to assimilate, ‘beat the odds’, reject the terrible statistics that kept getting hammered in the media about Māori, and to be ‘normal’ or more white/European/Pākehā, like my dad. My mum wouldn’t talk about her whakapapa and we had a real disconnect to our Māori side; apart from Great Uncle Ben, who worked on a dairy farm down south, and Mum’s cousin Hohepa, who was in and out of jail (and bought me my first ever Strawberry Shortcake doll, which made him my favourite relative).

Māori people depicted as normal, as superheroes, as complex characters, not as other, a different class to be constantly picked apart

One thing that did connect me to te ao Māori, however, was books. We are a family of readers – that is the one good thing my dad instilled in us, and is something I have passed down to my children. We consume information on a daily basis through reading and looking at pictures. This is where I learnt about pūrākau – fantastical stories of cheeky demigods and supernatural phenomena, te reo Māori as a poetic and descriptive device and, overall, Māori people depicted as normal, as superheroes, as complex characters, not as other, a different class to be constantly picked apart. Books have always been an escape – a way to be transported to another time, dimension, place, to be outside of yourself and to be in someone else’s shoes, a place where you can exist free of judgements.

The value of books for children is priceless, and the value of te reo Māori pukapuka for tamariki is taonga.

It is this shared love of pukapuka that prompted me and my hoamahi, Alyce Stock, Jill Bowie and Elspeth Moody from Kā Kete Wānaka o Ōtepoti (Dunedin Public Library), to curate an exhibition of children’s pukapuka celebrating the Māori artists and illustrators who have helped to keep te reo Māori visible and alive. All of the books are from the Heritage Collections and most of them span the time period from the 1960s to the 1990s. The aroha that pours from these pukapuka is real and determined, and to be able to share them is a privilege.

Ko Au Tēnei nā Patricia Grace rāua ko Robyn Kahukiwa. Auckland, N.Z.: Longman Paul, 1985.

The whakamā I have felt about being Māori is complex, and shared with many other tangata whenua, so to work on a project like this is a start to overcoming that feeling and replacing it with mana and aroha. The act of elevating these pukapuka to exhibition status, and making sure that te reo Māori is evident in all signage and writing for this exhibition, is vitally important for us as a rōpū to create a safe and accessible space within a historically colonial library collection and system.

As my colleague Alyce says, for Pākehā, doing this kind of work is a real and practical way of being good Tiriti partners – giving the general public access to the information and taonga that are buried deep within institutions is essential. The kaitiaki of collections within these institutions need to be cognisant of other voices and perspectives that are not represented by their staff – they also need to let outsiders in from time to time to look at things from another angle.

important for us as a rōpū to create a safe and accessible space within a historically colonial library collection and system

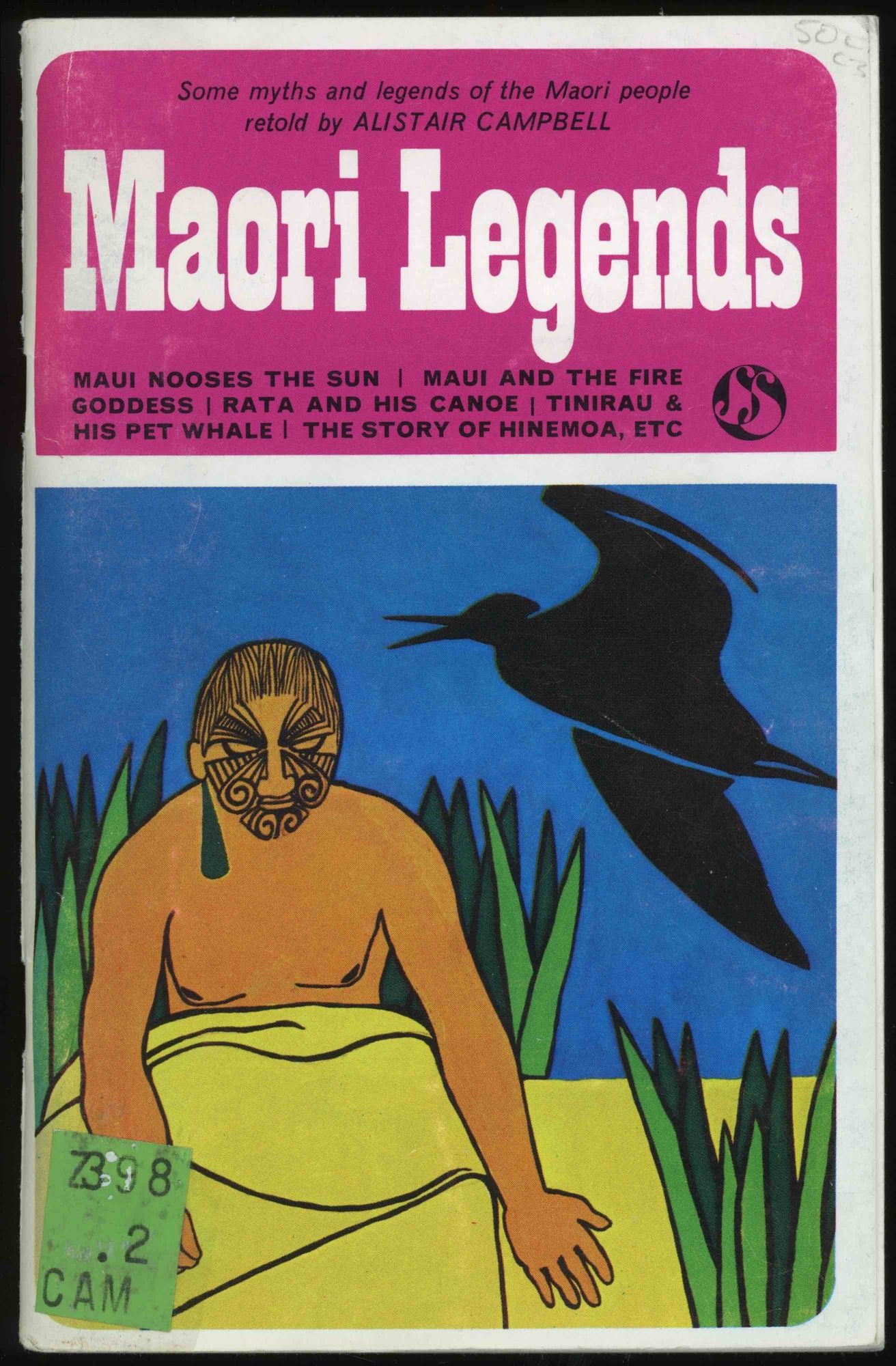

Throughout the process of researching and synthesising information, collectively we found some true legends. One of the first pukapuka we found illustrated by a Māori artist is Māori Legends, written by Alistair Campbell and illustrated by Dame Robin White (Ngāti Awa) in 1969. This pukapuka became our first pou – our starting point for the visual representation of a Māori perspective and the title for the exhibition.

Maori Legends: Some Myths and Legends of the Maori People nā Alistair Campbell i tuhi; nā Robin White kā whakaahua. Paraparaumu, N.Z.: Viking Sevenseas, c1969.

Māori Legends is a play on words: the exhibition is about Māori stories and Māori legends – the artists who illustrated those stories. I was fortunate to be able to interview Dame Robin White about her experience during that time, and asked her what she thought was important about children's books. She says:

Mmm, it's interesting. I like that question, and I had a few conversations with my husband, with my sister-in-law, one or two others. It's interesting how people have different opinions about, you know, what children's literature should be like. And then I also have the experience of what I was exposed to myself as a child, and what the benefits are that I reaped. What were the benefits to me of how I was introduced to literature, and the kind of literature that I was introduced to. And I think the thing that sits foremost in my mind, in my thoughts, in my hopes for children's literature is that it exposes children to beauty. I mean, the beauty of language, the beauty of thought and action so that… it elevates their tender souls. You know, children are like these little tender plants that can bend and grow in any way they're influenced. They're really susceptible to influence. So, it's a powerful influence, isn't it, literature and books? And this is a means to influence children along the right path so that the potential for good within them is nourished and the potential for going the other way is inhibited because any child can go either way. So I think there's a huge responsibility to provide the best for children. I really dislike the idea of dumbing down and using language that kind of mimics street talk, because it's hip, because it's cool. And sometimes there is a place for that, but… how does it contribute to refinement… and… yeah? And let's look at the experience of language in a traditional Māori context. Before Europeans came there was, you know, no written language, but children would have been exposed constantly to the finest form of poetry. Beautiful use of language. You don't even ... you don't have to understand te reo to understand that these are great artists who stand up on the paepae and… you just listen and it's just so thrillingly beautiful.

Te reo Māori was literally beaten out of whole generations – children were punished for speaking their language. Between 1900 and 1960 the numbers of fluent te reo speakers went from 95 percent of Māori down to 25 percent, exacerbated by educational policies. Community leader and educationalist Hoani Waititi (Te Whānau-ā-Apanui, 1926–1965) created the series Te Rangatahi: A Māori Language Course, published in 1962, as a way to keep te reo Māori in the education sector. As a supplement to this, he also created Te Wharekura, a Māori-language school journal that came from a Māori perspective and also enabled native speakers to become proficient in writing, helping the language to survive. Through Te Wharekura, contemporary Māori artists and writers such as Kātarina Mataira, Cliff Whiting, Ralph Hotere and Robert Jahnke dipped their toes into illustrating and writing stories for Māori, creating a pathway to becoming full-time visual artists.

Before Europeans came there was, you know, no written language, but children would have been exposed constantly to the finest form of poetry.

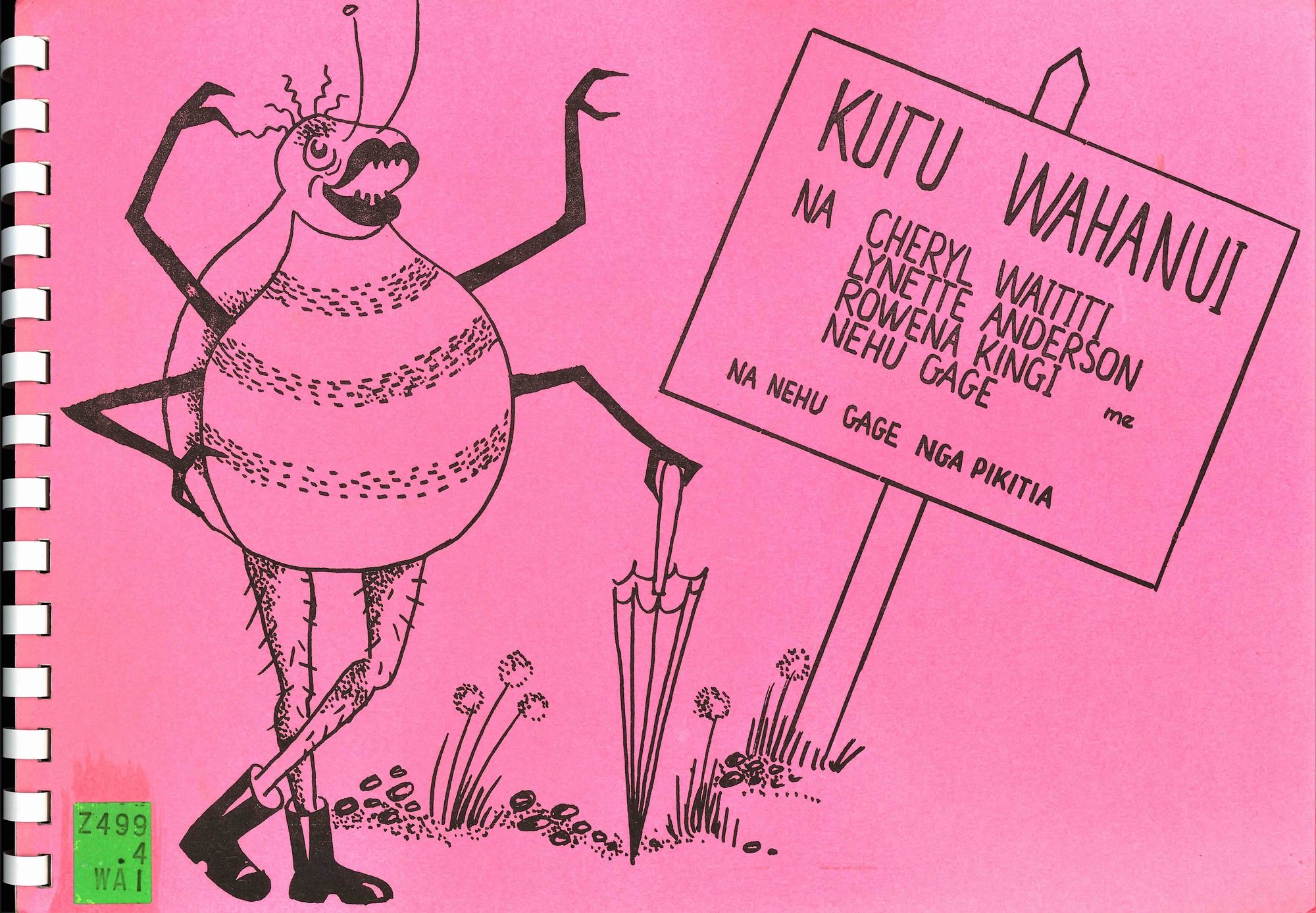

Following on from this, Dame Kāterina Mataira created her own kitset of Māori-language readers[1] in the 1970s. The kitset came with a cassette tape of Mataira reading sentences and singing waiata. She asserts that “bilingualism is the inherent right of every New Zealand child since he derives from, and shares in, a bicultural society”.[2] The picture books, “essentially for children to look at and be read to”,[3] were deliberately published in black and white so that they were easy to reproduce and so that children could colour them in themselves. Created by various writers and illustrators, they span a range of topics and have all sorts of colourful characters – everything from a ghost (Kīkī Kehua) to a flea (Kutu Wahanui). Mataira made these for a Preschool and Junior Primary Māori Language Programme during her time as a research fellow at Waikato University. Credited as being the ‘mother of Kura Kaupapa’, Dame Kāterina Mataira was a true visionary and educationalist, forming her own model of learning – Te Ataarangi – and going on to author and translate many pukapuka for children and adults.

Kutu Wahanui nā Cheryl Waititi rātou ko Lynette Anderson ko Rowena Kingi i tuhituhi; nā Nehu Gage kā whakaahua. Hamilton, N.Z.: Centre for Maori Studies and Research, University of Waikato, c1976.

Finding these pukapuka was magic – this is the taonga that is not easily accessible unless you know what you are looking for, but when you do find it, it is powerful. The sheer determination that went into publishing some of these books is phenomenal and foundational. Without the groundwork these artists, authors and educationalists put in, we would be in a very different place today.

Reading a picture book in te reo Māori is a political act of aroha that we can all do.

Now, as an adult living in Ōtepoti Dunedin, I still see racism. Thankfully not coming from any of my friends’ sisters, but it exists. One thing we can do to beat those ideologies is continue to highlight, celebrate and educate through showing exemplary work by Māori artists, authors and creatives, sharing te mamae me te aroha – the pain and the love – from historical events, redressing misinformation and giving awhi in any way we can. Reading a picture book in te reo Māori is a political act of aroha that we can all do.

Māori Legends

25 June – 9 October 2022

Reed Gallery, 3rd Floor, Dunedin City Library

[1] Kāterina Mataira, Oma Rāpeti (Hamilton: Centre for Māori Studies and Research, University of Waikato, c. 1976).

[2] Kāterina Mataira, Nga Tohutohu: Teaching Manual, Preschool and Junior Primary Maori Language Programme (Hamilton: Centre for Maori Studies and Research, University of Waikato, 1977), 1.

[3] Ibid, 1.

This essay is featured as part of Issue 07: Aroha, guest-edited by Natasha Matila-Smith. Click here to read more contributions.