Scepticism and Community: Considering Howick's Malcolm Smith Gallery

Lana Lopesi reflects on the recently opened Malcolm Smith Gallery and the challenges it faces as a community art space.

Lana Lopesi reflects on the recently opened Malcolm Smith Gallery and the challenges it faces as a community art space.

As an active, creative concept, the adda community demands us to begin from the notion of the impossibility of belonging. It calls for a continual un-working of the totalising and exclusionary myths of collectivity upon which community is purportedly formed.

– Balamohan Shingade, ‘The Adda Community’

I first got wind of the changes taking place at UXBRIDGE Arts & Culture over a coffee with Ioana Gordon-Smith, curator at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, and Balamohan Shingade, manager and curator of UXBRIDGE’s Malcolm Smith Gallery, then under construction.

Ioana and I were commissioning a series of essays for Localise, a ‘newspaper’ to accompany last year’s Whau Arts Festival. We wished to explore issues that lacked critical attention – that artists and curators weren’t taking seriously enough. One of these was community art. What, we wondered, did high quality community art look like? And how could you foster it?

Knowing that Shingade was new to his position, we were interested in the ‘strategies and measures’ he was planning to take to the East Auckland community of Howick in which UXBRIDGE was situated. A big question, and maybe a slightly unfair one to ask such a young curator, but Shingade was up for the challenge. His essay, ‘The Adda Community’, unfolded into a manifesto of sorts.

11 June 2016 marked the closure of the ex-Presbyterian church previously used by UXBRIDGE for art exhibitions and performances of all kinds (the space is currently being turned into a theatre), and the opening of the brand spanking new Malcolm Smith Gallery. Gone is the quirky, slightly dingy, all-wood interior. Now we have a clean, white cube designed by Creative Spaces.

The Gallery takes its name from one of the people who founded UXBRIDGE in 1981, an architect who “envisaged a centre for his hometown that would be a beacon for the art and ideas of its day”.

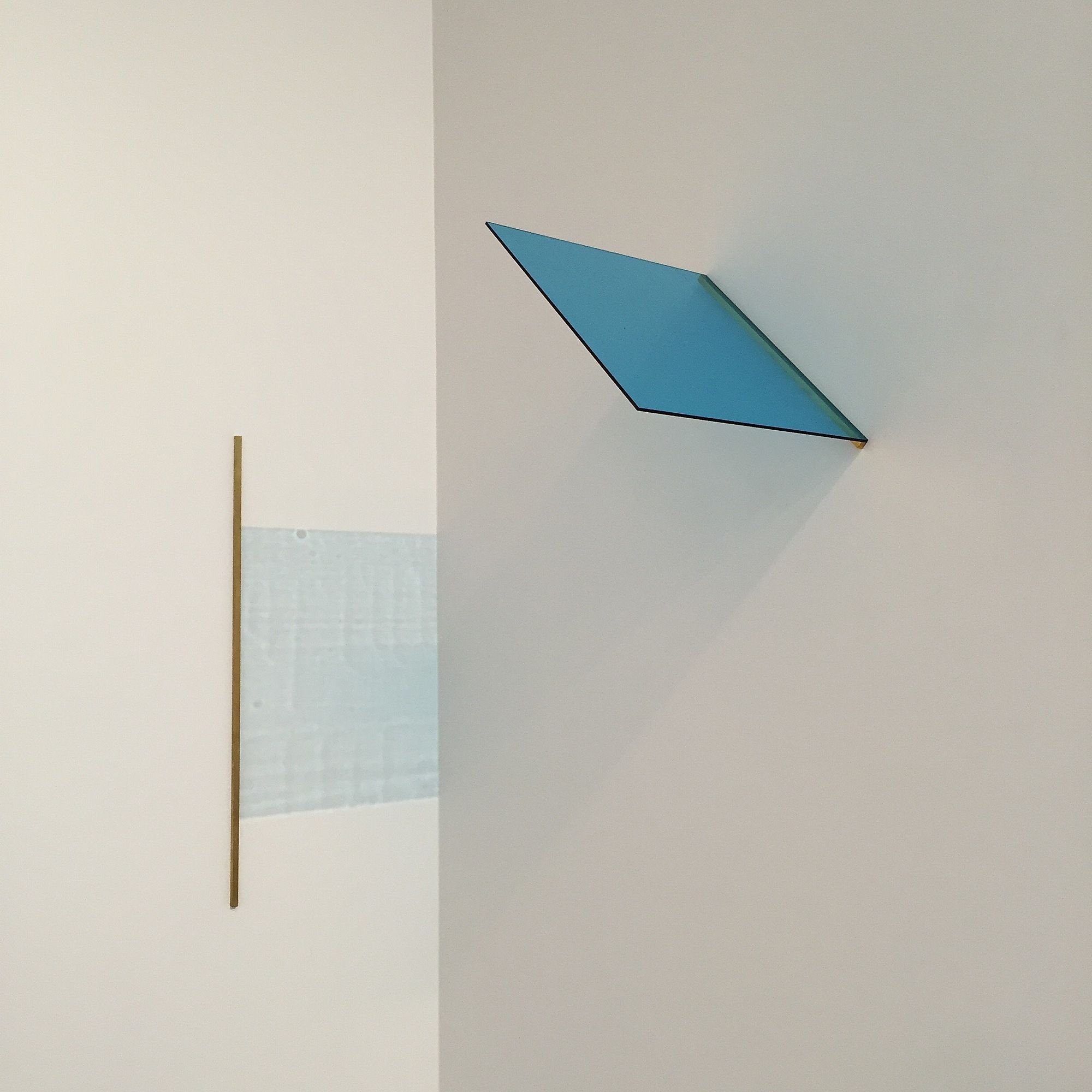

The inaugural exhibition, Soft Architecture, takes its cue from Smith’s profession, centring on art works that relate to architecture. The show includes work by a range of contemporary Aotearoa artists: Katrina Beekhuis, Claudia Dunes, Richard Frater, Samer Hatam, John Ward Knox, Jeremy Leatinuʻu, Shannon Novak, Jeena Shin, Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, and Julia Teale.

With the new space comes an ambitious vision to embrace both local and international contemporary art. Recognising the high Asian population of Howick (near 40%), the Gallery hopes to shape “the success of Asian arts and cultural practices in Aotearoa”.

It’s an exciting prospect. It’s about time we saw a space dedicated to supporting contemporary Asian art. The pan-Asian New Zealand population is projected to grow to 1.26 million by 2038 – surpassing the Māori population and becoming second only to the ‘European or other’ demographic.

If Malcolm Smith Gallery is going to find a unique place for itself so close to Te Tuhi in Pakuranga, this seems an appropriate mission to declare.

*

There is, with adda, a refusal to mortgage the concept of community to identity. Adda is a network of relations that is concerned not with race, class, gender, sexuality and culture, but instead, it is a community that is composed via relations formed across and against these categories. In adda, the bond is that which is commonly open. After all, nothing is expected in adda but idleness and palaver, with the quality of the conversation depending on the relational moods and mind-sets of its participants.

– Balamohan Shingade, ‘The Adda Community’

An elephant in the room – and a problem that Malcolm Smith Gallery has effectively set itself up to combat – is the racial and class tensions that exist in the Howick area. For instance, in 2011, a Christchurch-based, white supremacist group called Right Wing Resistance distributed “stop the Asian invasion” flyers in Northcote, Pakuranga, and Howick.

The following year saw the launch of a campaign, led by the Bucklands Beach Action Society, to prevent the construction of Thurston Place College. This school was to be built in Howick to cater for up 100 young people in Child, Youth and Family care whom authorities believed would benefit from an alternative education.

Residents made comments like, “If I wanted to be surrounded by these cultures, I’d have bought a house in South Auckland.” Some feared that property values would plummet, crime rates and insurance premiums would rise, boats at the local marina would be damaged, and their children would be in danger. Some were quoted as calling it a “prep school for Mt Eden jail”. Charming.

And let’s not forget about the 2004 arson attack on Te Whare o Torere (later rebuilt and renamed Te Whare o Matariki), on the same grounds as UXBRIDGE. A whare! A building associated with the rightful owners of Aotearoa!

One could claim that these were isolated incidents and insist that people say and do stupid things no matter where they live, but the two exhibitions curated by Shingade at UXBRIDGE prior to the opening of Malcolm Smith Gallery suggest that he has no intention of turning a blind eye. Racism is clearly something on his mind.

His first exhibition was Te Taniwha & The Thread by Joyce Campbell, in collaboration with Ruakituri historian Richard Niania. Here, Shingade declared a connection between his curatorial programme and tangata whenua, acknowledging Howick’s rocky recent history, and making it clear that Ngāi Tai kaumātua would play a role in Malcolm Smith Gallery.

The second exhibition, Mahābhūta: The Great Element by Tiffany Singh also signalled a mending of relationships, this time between UXBRIDGE and the nearby Buddhist temple Fo Guang Shan, where UXBRIDGE holds an annual satellite show.

Previous exhibitions showed little consideration for the religious surroundings. On one occasion, for example, a naked bust was displayed. For Mahābhūta, Singh and Shingade took extra care to ensure that the work would not offend the nuns, even removing the artist’s signature wax sculptures of the Virgin Mary.

While the motives behind Shingade’s programme are not lost on me, and while it’s great to see him tackle such complex issues, I wonder whether a gallery of this scale (or any community gallery in Auckland for that matter) can hope to address them to a meaningful extent.

*

Adda is a community without bondage. As a kind of place/practice, adda opens other possible and potential networks of relations, of living and being with others. The opposite of community, after all, is not purposelessness but loneliness. In this way, a community is conceived as a process within which to experiment by way of social links, connections, and relations, even though the impossibility of collectivity continues to haunt the very activity of the adda community.

– Balamohan Shingade, ‘The Adda Community’

Another elephant in the room is ‘engagement’, a phenomenon that everyone talks about but few seem to understand. I wonder who is walking through the doors of Malcolm Smith Gallery, and what the draw card is for them.

I am rooting for the organisation, but when I read that to “inspire and challenge its audiences, the Gallery will strive to encourage dialogue, foster creativity, and explore meaningful new ideas with insight, imagination, and intelligence,” I can’t help but notice the profusion of buzz words. It sounds like Auckland Council-speak.

We’ve seen a scary turn for community art spaces in the recent restructuring of the Council. Control has been shifted from the gallery coordinators – who are responsible for the day-to-day running of the spaces, and who have actual interaction with audiences – to a team of Ponsonby-based programmers, each spread across two galleries.

On top of this, the spaces offer little to nothing in the way of artist fees. (How artists are supposed to create work of any quality is beyond me.) Instead, we see an outsourcing of initiatives for large sums of money to ‘creative agencies’ such as Alt Group and Fresh Concept, who brand community art through POP, and facilitate events like Urbanesia.

The success of all of this is still measured primarily by counting people – a system that represents only superficial levels of engagement.

The situation is slightly different for UXBRIDGE, which is more autonomous. On the surface, it seems to operate on a similar model to facilities like Corban Estate Arts Centre and Lake House Arts Centre, whose day-to-day business includes art classes, studios for hire, maybe even a theatre or café.

The problem is that the galleries associated with such organisations are really subordinate, and must ask what they can offer the regular attendees of lessons and plays. Will Malcolm Smith Gallery be able to buck the trend?

Community art in Auckland seems, in many ways, to be fighting with itself. Its ultimate goal is to serve local audiences, though it may also declare an ambition to engage with the international art world, as Malcolm Smith Gallery has done.

The dominant approach taken by suburban galleries seems to be to reflect and serve the community by devising a programme tailored to perceived need, then finding art that fits. The issue here is that without the right curator, the programme can end up feeling prescriptive, repetitive. It can be boring.

By contrast, central Auckland galleries, such as Artspace and Objectspace, and those with stronger curatorial teams, such as Te Tuhi and Te Uru, seem to concentrate on coming up with broadly interesting shows, then aiding in audience support.

My impression from Soft Architecture is that Malcolm Smith Gallery is aiming for this second model. Whether the institution will succeed in engaging the community remains to be seen. Art audiences responded well to ‘The Adda Community’, but can it translate into effective, real-life exhibition-making that will attract, interest, and enlighten locals?

With so few examples of high quality community art facilities to hand, it’s hard not to be sceptical. Here’s hoping that Malcolm Smith Gallery, under the stewardship of Balamohan Shingade, will pull off the trick.

Main image: UXBRIDGE Arts & Culture, 2016. Photograph by Francis McWhannell.

Soft Architecture

Malcolm Smith Gallery, UXBRIDGE Arts & Culture

13 June to 16 July 2016

Free admission