Machines of Seamless Chaos: On Joseph Herscher

Georgina Langdon-Pole on Joseph Herscher's elaborate Rube Goldberg tributes

I’ve lived with an array of remarkable characters over the years, none of whom are comparable to Joseph Herscher. While most of us spent our flatting days partying, talking about the meaning of life, or settling the burning question of who left the condom in the toilet, Joseph was a man with different ambitions. He spent weeks designing extravagant sets for themed parties. He hosted flat craft nights. At one point, he got us all to participate in a bizarre algorithm dance featuring gimp suits, bondage gear and gigantic plastic breasts. Living with Joseph made you feel alive.

One night, as we pored over YouTube, our flat examined the world of Rube Goldberg machines: elaborate, whimsical contraptions designed to perform simple, everyday tasks. Each machine comprised a series of entertaining chain reactions. Sooner or later though, most of us stumbled to bed. But Joseph was stirred. He began to make his own Rube Goldberg – collecting the detritus we’d all accrued from our various jobs and unfinished projects and hobbies: discarded cardboard, marbles, canvas, levers and hammers.

Over the coming days and weeks, as we laughed, drank, ranted, went to work and came home, Joseph built, hammered, tinkered and drilled around us. Six months later we found ourselves encircled by a giant Rube Goldberg machine. One intricate chain reaction after the next, it wound its way around the walls of our lounge one slide and one switch after the other, ball to cup, pillar to wheel. It culminated with a Creme Egg being smashed to pulp at the end. Rightly, it took its place alongside the other contraptions on YouTube, and it’s outdone most of them – seven years on, it’s got over 2.75 million views. It was the first machine Joseph made, and it set something extraordinary in motion.

Today, Joseph is a full time kinetic artist based in New York. At the moment he is back in New Zealand, working on his most ambitious project yet: Jiwi’s Machines – a YouTube series featuring a range of corscuating devices, live actors, gags and slapstick comedy. The show is based on a character called Jiwi (Short for “jewish kiwi”, this was originally Joseph’s first name, and still is, officially, on his birth certificate. But after his mother received quiet counsel with friends about the name's wisdom in the playground, she caved in and opted for the more conventional “Joseph” instead). The premise is obvious, and gratifying: Jiwi makes machines to make his life easier, but they inevitably backfire, causing chaos to those around him.

I talked to Joseph recently about the joys and challenges of this project. We delved into his journey as a kinetic artist and discussed the process of making such sophisticated creations. We also grappled with the philosophy behind Rube Goldberg machines – specifically, what their playful and elaborate nature provides people in a world obsessed with production, consumption and efficiency.

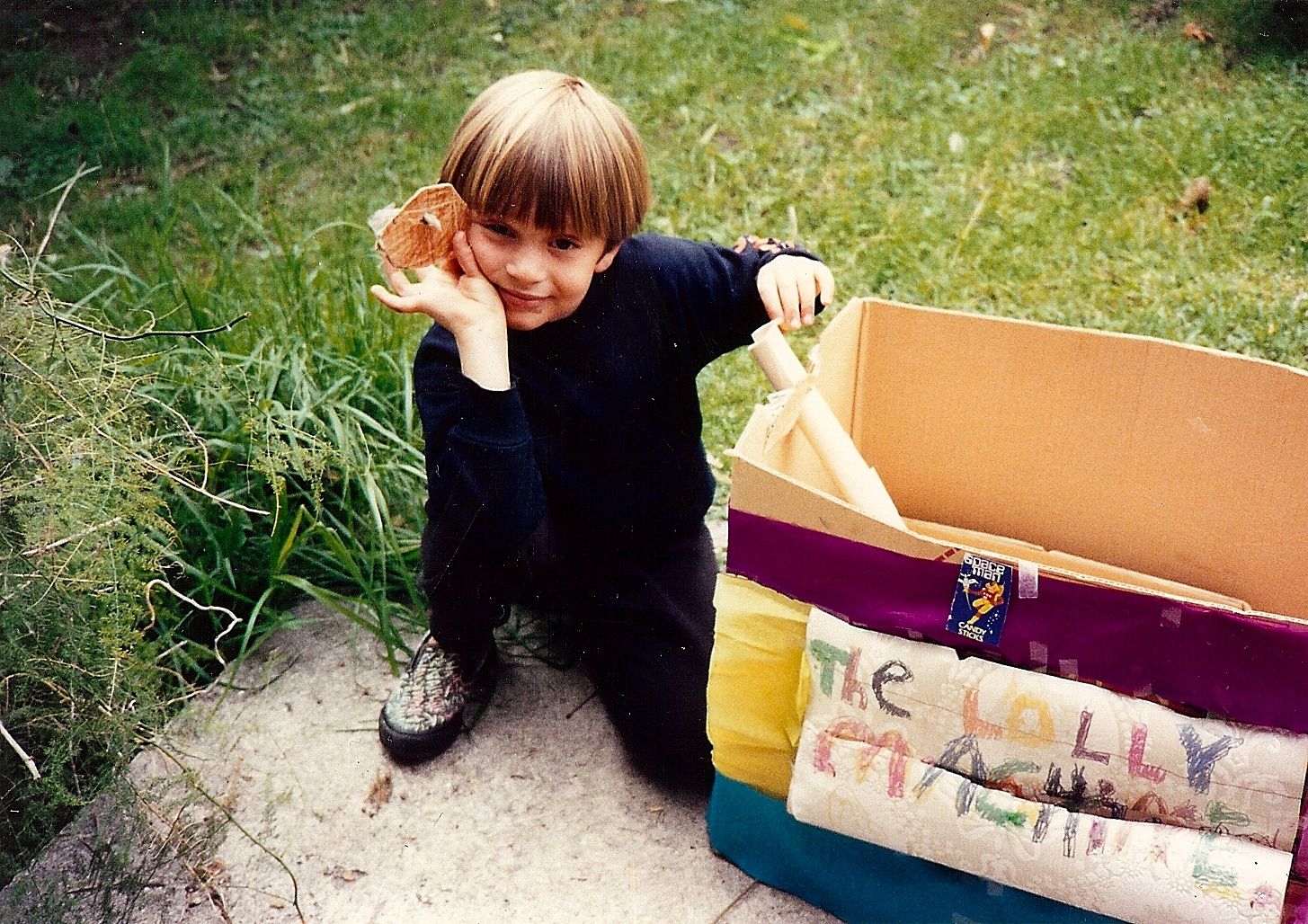

As a child, Joseph was always passionate about invention and design. At 6 years old, he made his first machine. “Its function was to store candy, but I also noticed it made my parents smile”, he says. Later, he created a book holder so his arms wouldn’t get tired while reading, and a machine that helped him pick fruit from trees. He was spurred on by utility, but also the delight he saw in those experiencing what he built.

“I love executing an idea to the point that I can tickle an audience in the same way that I’m tickled when I first think of the concept. That’s the biggest thing”, he says, reflectively. As a 7 year old he built a device to greet his mother when she came home from work late at night. When she opened the door it pulled a string, turning on a tape player with a recorded message: “Welcome home mum, I love you!”

Joseph grew up in Grey Lynn. His parents, Linn (Lorkin, from New Zealand) and Herschel (Herscher, from New York), are both talented musicians and artists in their own right. As a child he was encouraged to play and experiment. But he admits that while his childhood teemed with fun and creativity, it also lacked financial security.

Through his dad, the right to go Stateside beckoned, and our flat soon disbanded. This drove him to New York in his mid-20s, where he pursued a ‘real job’ in software development. It wasn’t long, however, before he was drawn back to inventing. Eventually, he abandoned his career altogether to make his Rube Goldberg machines full-time. Opportunities soon arose. Joseph’s work was included in the Venice Biennale. He starred on Sesame Street and was featured in the New York Times. His journey as a modern-day Rube Goldberg had begun.

“Rube Goldberg” has become such a shorthand for the sort of escalating, homemade flights of fancy Joseph and others have made that it’s easy to assume that the namesake was some sort of fictional mad scientist creation himself. Goldberg, and his equally influential English counterpart, Heath Robinson, were cartoonists and inventors active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Both drew cartoons of machines which performed simple tasks in convoluted ways. The period during which Goldberg and Robinson produced their best, most imaginative work was plagued by war, and driven by the immense technological development that war had set off. For the first time in history, standardised products were produced on a mass scale. Cars became widely available. Vacuum cleaners, irons, washing machines, fridges and heaters made their way to our homes. It was a time when our lives became more efficient than ever before.

Yet Goldberg and Robinson’s cartoons reflected scepticism of our increasingly interdependent relationship with machines. Goldberg described the machines he drew as symbols of "man’s capacity for exerting maximum effort to accomplish minimal results." By depicting contraptions, which completed small tasks in complex and long-winded ways, both artists challenged the role machines had begun to play in people’s lives, making light of our newfound obsession with efficiency, productivity and consumption.

Questioning our preoccupation with production and efficiency is something that resonates for Joseph – especially when technology is so thoroughly digitised, miniaturised, and intangible, and his wind-it-up and watch systems seem alive and vibrant by comparison . “If you get too far down the route of efficiency you become like a machine yourself. What’s the point in just getting to our final destination as quickly as possible? Our final destination is death,” he laughs. “We have to enjoy the process in some way, or what’s the point?”

Over time, his contraptions have become more and more impressive, setting objects in motion in peculiar and enchanting ways. In a knock on effect, marbles race through tunnels. Boiling water heats a sponge, causing it to tilt and release a ball. Eggs slide down picture frames. Chandeliers fall from the ceiling. Vases tumble off tables. Objects swing and bounce, collide and rebound in sequence. Their energies combined, Joseph’s machines have watered plants, poured drinks, made toast, turned the pages of a newspaper and got him dressed.

Like myself, Joseph came of age in the 1990s, a time when computers exploded into our lives. Computers connected global economies and networks, production and consumption thrived – yet we became ever-more detached from the means that gave us our ends. Today, as we come to terms with the unsustainability of a system centered on speed, growth and efficiency, Joseph’s machines enable people to appreciate process, rather than the end product or result. Every chain reaction in his machines is intriguing. They move at speed. There is little time to anticipate what comes next, or what’s just been. Your deepest concern is with the passage of a marble, or crashing cup, or flicking pencil. You can’t help but become absorbed in a series of fleeting moments.

Joseph’s practice is about grounding people in the moment, but it also urges people to reimagine the objects around them. Children’s minds are expansive. To them every item in a given environment is versatile, their possibilities constantly recast. Sooner or later, adults introduce toys as objects of play; separate from objects with function (typically, those objects that need protecting from small, relentless hands). And often, this subdues innovation.

“There’s a certain amount of playfulness that we drill out of kids from an early age,” Joseph stresses. As children become accustomed to the rules and values of the adult world, objects begin to be classified by efficacy and social rank. Empty toilet rolls stop being microphones and telescopes. Pots cease to be helmet props in dramatic roleplays. In line with a society gripped with consumption, objects become effigies of status and identity. And Joseph rescues the most everyday ones to curate them in obscure ways, challenging these classifications, encouraging people to see their surroundings anew. “That’s my biggest inspiration, I guess: to use objects that we see and use every day in a way that we’ve never used them before”, he says.

The making of such complex machines calls for an understanding of the basic rules of physics, a dry reality under which these systems work or don’t - yet there is also a magical and playful quality to the legacy Jiwi’s Machines inherits. Joseph doesn’t see the different expectations as irreconciliable, his own thinking oscillating quickly between scientific logic and creative ingenuity. His process involves a ‘research’ or ‘play’ phase to generate ideas. This is tactile in nature. He spends time experimenting with the potential of an object: how it feels and travels, and what it’s capable of doing.

Next comes the problem-solving phase, which is more scientific in nature. Here the focus on manipulating objects and examining how they react with one another. The gratification when something works is immensely rewarding. “I guess that’s the most satisfying thing – when you have an idea that makes you laugh inside. You go through hours and hours of work, problem solving and challenges, and then you finally get that moment when you see it for real.”

Although Joseph finds serenity in creating, the uncertainty that comes with manipulating such intricate machines is also ridden with anxiety. If you knock one end of a stack of similar-sized books, they fall like dominoes – other materials aren’t so predictable. “It’s like trying to tame a wild animal – trying to get balls to bounce at a certain angle, or water to splash in a certain way. There’s an inherent amount of chaos to the world around us. I feel like I’m trying to tame that chaos, but often, it doesn’t want to be tamed.”

On YouTube, that first machine he made when we lived together looks like the spur-of-a-moment product of an afternoon’s work. In practice, it took a grueling 600 takes to film. The cardboard was from around the house in different stages of condition and decay, and even a change in humidity would intercept the machine’s chain reactions. Over time he’s become adept at picturing the contraption in his head first, simulating mentally whether or not a sequence will work. Though he admits it’s still testing, that lack of control – going through several stages just to find out whether or not something works in the way you want it to.

The joys and pitfalls of taming machines were particularly confronting during the filming of Jiwi’s Machines. The tensest moment of filming hinged on an essential, uncooperative part of one of the contraptions - a parrot eating a grape. It was the foreman. Without it, the machine couldn’t be set in motion. The crew huddled around the parrot, dangling the grape, luring it to the other end of its cage. It was full and tired. Stubbornly, it refused to move from its perch. Although laughing on reflection, Joseph maintains that this was one of the most nerve-racking moments of his adult life. “If we hadn’t got that shot, the project would have collapsed – it was a very important scene. In a way, this was the most important project of my career. I was banking on it taking me where I wanted to go. My entire career was resting in the hands of this parrot, and whether he felt like eating a grape or not,” he chuckles.

Eventually, the parrot ate. I can’t help but smile when I imagine Joseph desperately coaxing it. Because it’s ridiculous, but it’s also testament to the passion and persistence he has for getting the absurd right. Like many artists, his process is often arduous and fraught with uncertainty. But when the parrot finally eats the grape, or the hamster shuffles across its cage like it should; when an object drops in seamless chaos, or a marble travels with grace along the most convoluted of voyages, it is astonishing. As you watch it happen, the child inside you stirs and surges. Best of all, when you see Joseph’s machines work, you can’t help but laugh out loud, the same way he does the moment he brings an idea to life. Of all the different components of his inventions, that might be the best and most salient one.

Jiwi's Machines is available now, free-to-view in all its coruscating glory, on YouTube.