Loving Harry Styles: On Fantasy Relationships and Self-Care

Fantasy relationships with celebrities can actually be a form of self-care, writes Hannah Banks.

It's 1998 and I’m sitting in my sister’s room. There’s this alcove where her dresser sits, and plastered over those three walls are posters of Leonardo DiCaprio, the kind you pull out from teen magazines. I still remember the day we went to see Titanic together. At the end, when Rose lets go and Jack sinks into the water, I sneaked a glance at my sister: she was weeping. That alcove in her room was a shrine to Leo and I adored it. I didn’t understand that kind of crush yet, but I knew that it was exciting, and I couldn’t wait to have one.

Fast-forward to 2011 and I’m reading How To Be A Woman by Caitlin Moran, where I come across this quote that creates a lightning bolt of recognition inside me:

I imagine possible relationships all the time. All the time. My God in my teens I was fucking tragic for it. I scarcely existed in the real world at all. I lived in some kind of…sex Narnia. My love life was busy, exciting, and totally imaginary. My first serious relationship was conducted with a famous comedian of the time, and took place wholly in my head. I’d never met him, spoken to him, or even been in the same room as him – and yet, during one Inter-City journey from Wolverhampton to London Euston, I had one of the most intense relationship experiences of my life: all daydreamed.

I realise: I do this! Specifically, I do this with musicians who have curly, dark-brown hair. I also think: if Caitlin Moran does this, maybe it’s kinda normal. I decide to casually mention one of my imagined relationships to a few friends, and it seems to unlock a treasure chest of secret fantastical love affairs that they’ve all had. These relationships are always detailed and ‘realistic’ to some extent – they just happen to bump into them outside the gig venue; or they go to the same café every morning in Brooklyn – there are timelines, major plot points and recurring scenarios. There’s a freedom to these conversations about our imagined realities where reality itself isn’t important, whereas talking about crushes or unrequited love in our actual lives always has real-world consequences. It can be quite upsetting to imagine what might happen at that upcoming party, and then be inevitably disappointed when the perfect scenario in your head doesn’t play out in reality. But when it’s a fantasy with someone you’ve never met (and likely will never meet), you are free to let your imagination run wild.

This is by no means a new idea. It even has a scientific name: para-social relationships. These were first written about by Donald Horton and Richard Wohl in 1956 in their article ‘Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance’. With the explosion of television in the 1950s, Horton and Wohl discussed a new characteristic, the “illusion of face-to-face relationship with the performer”, and they proposed to call this “relationship between spectator and performer a para-social relationship”. While I think it’s also possible to experience an imagined or fantasy relationship with someone you actually know, Horton and Wohl focus on the illusion of intimacy in parasocial relationships and how this creates a bond between the spectator and performer. They write, “We call it an illusion because the relationship between the persona and any member of his audience is inevitably one-sided, and reciprocity between the two can only be suggested”. That may have been so in the 1950s, but the growth of the internet and social media has given fandoms even more access to those they adore, often willingly provided by the ‘personas’ themselves via Instagram live videos, interaction on Twitter, or VIP meet-and-greet packages at concerts. They can now easily create the illusion of intimacy with their fanbase, even if it is one sided. If this is taken to the extreme it can become erotomania, where the individual starts to believe that the focus of their parasocial relationship actually loves them back.

I always conjured up these romantic trysts in times of devastating heartbreak or extreme stress

In 2002 David C Giles published ‘Parasocial Interaction: A Review of the Literature and a Model for Future Research’. Giles wrote that, “Although a profoundly psychological topic, the implications of parasocial interaction have received little consideration from psychologists”. Giles reviews all the literature on PSI since the publication of Horton and Wohl’s article, and points to research from the 1970s that concluded that “PSI’s most important function was as a source of alternative companionship, resulting from ‘deficiencies’ in social life and dependency on television (i.e., as compensation for loneliness)”. It’s quite a bleak spin, but this is an aspect of my fantasy relationships that really resonates with me now. While I wouldn’t use the word ‘deficient’, I am far more likely to engage in para-social relationships when I’m single, and as Alan Rubin and Elizabeth Perse argue, “PSI may arise from an altruistic human instinct to form attachments with others, at no matter how remote a distance”.

Humans need attachment to others, no matter the distance between them. The brutal reality of this need came crashing down on me a few months ago. I moved to Australia at the beginning of the year and am now in lockdown by myself, far away from friends and family, and I’ve found myself briefly revisiting all of my fictional relationships. Of course, they’re really not the same as a hug from my actual loved one who is across the Tasman, but they still provide some comfort to me. Cohen writes that while “Parasocial relationships mostly lack the behavioural components that typify other social relationships…they seem to share many of their emotional aspects”. My imagination can at least provide me comfort and joy, and this will have to sustain me until we can hug again. In their article ‘Parasocial Relationships and Self-Discrepancies’, Jaye Derrick, Shira Gabriel and Brooke Tippin write that the experience of empathy is hugely important in parasocial relationships. They state that normally “empathy is an affective reaction produced in response to another person’s emotion” and that “in real relationships, empathy is strongly related to relationship closeness”. I’ve always considered myself to be an empathetic person and I care deeply about the people around me. Empathy is crucial to the construction of a parasocial relationship. As these interactions are not reciprocal, “empathic reactions represent the majority of emotional reactions” within a parasocial relationship.

I had never really thought that much about the significant parasocial relationships that I’ve had, until a couple of years ago. Obviously, I thought about each one in great detail at the time, but I had never realised the connection between them all. Not only were they with musicians with curly, dark-brown hair, butI always conjured up these romantic trysts in times of devastating heartbreak or extreme stress. While they were based in reality, I was creating a full imaginary world, a “paracosm” each time; they were an escape, a safe haven. When I was sitting on the train, or running, I listened to their music and created whole other lives in my head. I would replay significant scenes or moments from these imagined timelines to help me get to sleep at night. At the time they were perfect relationships, because I couldn’t (or maybe wouldn’t) be hurt within my own imagination.

While my real romantic life was dire, I was having the loveliest time in my imagination

I spent a lot of the late 2000s in a state of perpetual heartache. I was a sucker for unrequited love and didn’t have the confidence to do anything about it. But around the time of my 21st birthday my sister showed me the video for ‘Little Lion Man’ by Mumford and Sons, and I found an escape. First, I loved the song. Second, I fell absolutely in love with the curly-haired piano player – Ben Lovett. I proceeded to watch every interview and video I could find. He was articulate, funny, and perhaps the slightly more sensible one. So, while my real romantic life was dire, I was having the loveliest time in my imagination. Magically, in this alternate reality I was living in London and we met at one of their gigs. It was fun, gentle and romantic. Most of the scenarios involved him playing the piano while I sat in a comfy chair. Although, memorably, for one of his birthdays I made him the piano cake from the Australian Women’s Weekly Children’s Birthday Cake Book (it’s a classic and definitely better than the castle).

Unfortunately, there can be problems when you actually encounter the real person of your parasocial relationship. Caitlin Moran writes about this, recalling being at an event with that famous comedian where a friend had to stop her from confronting him, reminding her that none of it actually happened, they didn’t actually have a child together.

Naturally, I was thrilled when Mumford and Sons announced they were playing in New Zealand at the end of 2012. They were one of my favourites and I would get to see them live. I knew how they arranged themselves on stage and you best believe that I was in the second row, closer to Ben’s side. We were going to meet at this gig. Somehow, he would see me and then, by the miracles of fate with a dash of romantic movie magic, he would bring me backstage. The whole thing would start from here now. The gig was incredible, I wept my way through it. And during the encore, Ben made eye contact with me and smiled, this slow smile that I had seen him do in interviews. It’s like sunshine breaking through clouds. I didn’t get to meet him.

In his article ‘Parasocial Breakups’, Jonathan Cohen writes that “parasocial breakup is quite common”. He agrees that these dissolutions are not as traumatic as the end of an actual romantic relationship or losing a close friend. Nevertheless, “the sadness associated with parasocial breakup is most likely a significant and recurrent feature of viewers’ emotional lives in general and of their experience with the media, more specifically”. I’ve never experienced a full parasocial breakup, probably because of my tendency to imaginatively pursue musicians. They don’t disappear like a television character can, they might just be quiet for a while depending on where they are in their album/touring cycles. I also don’t experience the jolt of the character transforming back into the actor. Rather, what I experienced at the Mumford and Sons gig was disappointment in my own expectations. I had pictured a completely unrealistic scenario of getting to go backstage. I knew this wouldn’t happen, yet I was still a tiny bit disappointed when my imagination didn’t transform into reality. But that smile is still burned into my memory. The parasocial relationship with Ben didn’t end, it just faded and then reignited when I saw them live again at the beginning of 2019. It wasn’t as intense as the first time, it was more like the memory of being in love with an ex-partner.

In their 2008 article Derrik, Gabriel and Tippin write that while parasocial relationships are obviously different to real ones, they also mimic our real relationships and protect us in several ways. They write that:

parasocial relationship partners can counteract rejection from a real relationship. Specifically, thinking about a favorite television show or character negates the mood and esteem effects of social rejection…. Thus, although people consciously know that parasocial relationships are not real relationships, in many ways they feel psychologically real and meaningful…parasocial relationships are also different from real relationships in that there is little to no face‐to‐face interaction and, therefore, little to no risk of rejection.

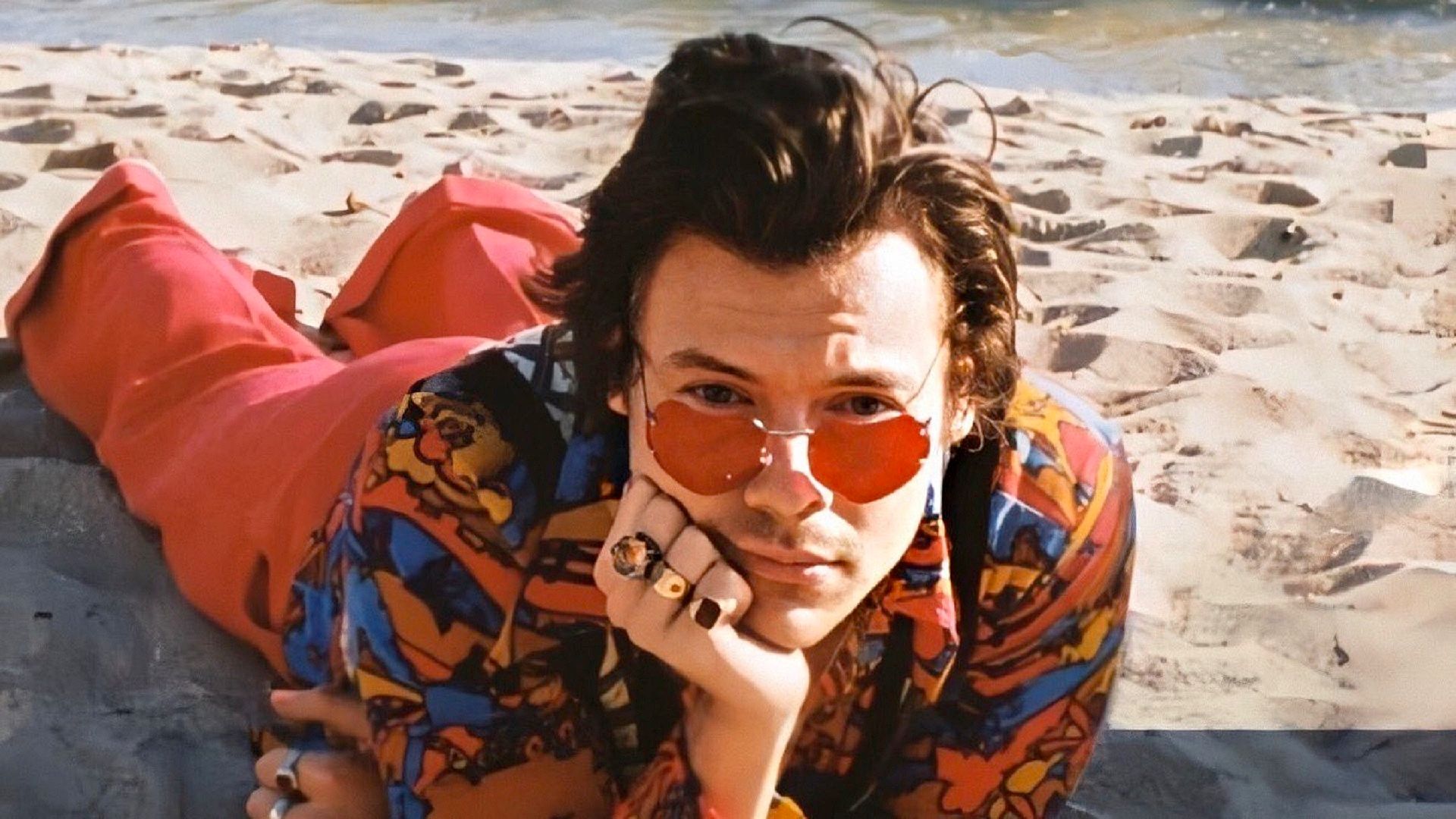

Earlier in this essay I wrote that what connects all my parasocial relationships is that I usually lean into them in times of heartbreak. I can’t be rejected inside my own imagination, so they are safe places to be when real life becomes painful. In 2017 I went through a pretty devastating breakup. Twice. I was also in the final stages of my PhD. In hindsight, I think I was actually looking for a new parasocial relationship even as I could feel my real-life one crumbling all around me. I needed something to think about other than impending grief and the intense pressure of writing a doctoral thesis. Fortunately, Harry Styles (another curly-brown-haired musician) released his debut solo album in 2017. Thanks to One Direction and their fandom of Directioners, there is a lot of content to consume online. The back catalogue of Harry Styles was more than enough to get me through the rest of my PhD. When I was stressed and sad, it was so comforting watching these lads having the best time together.Listening to One Direction, with their driving choruses (perfect for running) and lyrics that told me I was perfect, was the ideal serotonin boost.

For the next year I thrashed that debut Harry Styles album. It became inextricably linked with my PhD. I listened to it on my train commutes from the Wairarapa to Wellington, I learnt to play some of the songs on the ukulele, and I constantly imagined my alternate life and relationship with this incredibly kind and charismatic boy. In early 2018, in the final months of my PhD, the suits Harry wore on his solo world tour kept me going. Every few days new images would appear of Harry in velvet, floral, sheer, sequins, and I would discuss them with a friend. We analysed the fabric choices, connections to art history, glam aesthetics and femme silhouettes. When he wore a black velvet suit with sequined stars and lightning bolts we came up with a new hashtag – #WentFullBowie.

I started to look after myself by retreating into my imagination

I started to view this as a form of self-care. It wasn’t just distraction or procrastination, it brought me joy and allowed my brain to focus on something else for a bit. It’s difficult, in times of emotional distress and stress, to keep going and complete the necessary tasks. So I started to look after myself by retreating into my imagination. If I was alone and feeling overwhelmed (a common occurrence for a doctoral student), or was having trouble getting to sleep, I would spin through my parasocial narrative with Harry, pick a scene and play it like a movie in my mind. This particular paracosm was so detailed that imagining these moments was almost like a form of meditation. On the day I handed in my thesis my mum drove me to the train station. As she started the car, the radio came on and it was playing ‘Sign Of The Times’, the lead single from Harry’s album. Without irony I exclaimed, “It’s a sign!” And we drove to the station in the dark with Harry singing “We gotta get away from here.” It was a perfect reminder to let go of the stress I had been holding for four years. It was time to move on. I played that song a lot that day.

Now, in the darkest timeline of 2020, in the age of physical distancing, parasocial relationships are the only connections that some of us have. I have found that they’re even slipping into my real life and I’ve started imagining the actual reuniting hug I will eventually get to have with my boyfriend. It takes place at the arrivals gate of Wellington airport and it is a gloriously soothing thing to think about. I know that it’s not going to be exactly like the opening and closing scenes of Love Actually (which is what it currently resembles in my head), with soft lighting, gentle piano music, and a Hugh Grant voiceover. It’s going to be even better than that. It’ll be real.