Love Thy Trolls: What Pākehā Can Do About Online Racism

Julia Craig on what Pākehā can do to make online spaces safer for everyone else.

As the first few cases of COVID-19 in Aotearoa were being reported, the racist comments followed as if on cue. Racism exists (and thrives) throughout all of our structures of society in Aotearoa not unlike other colonised countries. Anti-Chinese sentiment in Aotearoa has been held up by anti-Chinese legislation since the first waves of migration in the 1860s. The abuse towards Chinese people and subsequently our Asian communities at large that ensued as Covid-19 developed was sadly, pretty predictable. In times like these we can draw upon initiatives like Tauiwi Tautoko, run by ActionStation, to rally around communities who are under attack, instead of turning a blind eye. So, while we are all confined to our own homes, allow me to introduce you to a way you can contribute positively to the online space, especially if you are (like me) Pākehā.

In 2018, a study undertaken by research company UMR found that one in three Māori, and one in five Asian and Pacific people experienced racist abuse and harassment online. The majority of this abuse was experienced on Facebook. A separate study by community campaigning organisation ActionStation and Senior Research Fellow at Otago University Dr Judith Sligo found that, on average, readers of Facebook comments encounter nearly five times as many racist comments as “kind or supportive” responses.

The research also shows the impact of this abuse on the individuals targeted, and it is largely unsurprising. The effects of online abuse range from an inability to focus on normal tasks to a loss of self-confidence and a lack of sleep.

I used to be very sceptical about the value of engaging with racism in the comment sections of Facebook. I was still sceptical when I began ActionStation’s Tauiwi Tautoko programme last year, which was developed in response to these sobering research results.

Tauiwi Tautoko (meaning non-Māori support for Māori) is a community of volunteers who trawl through the comment sections of our major media outlets’ Facebook pages to counter the racist and abusive pile-on that all-too-often happens. They are focused on challenging dis-, mis-, and mal-information publicly posted on Facebook that overwhelmingly targets Māori, Pacific, Asian, migrant and refugee communities.

I could not see myself actually starting conversations with Janets and Geoffs over whether people should speak te reo Māori on the radio.

Before undertaking the Tauiwi Tautoko training, I questioned whether it was worth the time and effort in terms of activism – surely there were loftier causes. I don’t even post on my own Facebook page. I consider myself an IRL over-sharer but very social-media-shy. I could not see myself actually starting conversations with Janets and Geoffs over whether people should speak te reo Māori on the radio. I actively avoid reading the comment sections of anything. After forcing myself to have a good look at some comment sections at the beginning of the training, I was not surprised to find that most comments following articles that had anything to do with tangata whenua, refugees and migrants were racially charged (if not outright hate speech).

But what was truly humiliating and shameful to me as a Pākehā, was that the majority of people bothering to challenge such speech were those from the minority groups being attacked. I realised at this point the outrageous privilege that allowed me to excuse myself from comment sections in the first place. Comment sections like these made me feel uncomfortable, made me feel ashamed to be part of the dominant settler-colonial group, so I removed myself quickly from that space and walked back into the comforting arms of amnesia and privilege. I turned a blind eye to racist trolls online because it didn’t seem worth the effort, or it was too disturbing to confront. Minority groups don’t have the privilege to remove themselves from spaces where they feel unsafe.

Minority groups don’t have the privilege to remove themselves from spaces where they feel unsafe.

At this point, it would be useful to define the term ‘racism’. Racism is not just individual racial prejudice, and not just the discriminatory and offensive things people say. Racism is, as Robin DiAngelo describes, “[the] economic, political, social, and cultural structures, actions, and beliefs that systematize and perpetuate an unequal distribution of privileges, resources and power between white people and people of colour.” In Aotearoa, the Pākehā settler-colonial culture is dominant, and controls the means of power in our society. Although everyone can have racial bias, and can discriminate, as DiAngelo points out, “when a racial group’s collective prejudice is backed by the power of legal authority and institutional control, it is transformed into racism.” When I talk about people who say ‘racist’ things in comment sections, I am referring to both the actual harmful and discriminatory words they speak, and the system that reinforces and supports them to speak those words.

In the Tauiwi Tautoko programme, there is a prescribed method for engaging with racist commenting on Facebook, and tauiwi follow a step-by-step guide, which has been refined by ActionStation in an ongoing consultation with educators and researchers. Above all, this kaupapa is Indigenous-led, following principles in te ao Māori:

- A slow and considered understanding of where the comment is coming from (āta whakarongo)

- Expressing ideas in terms of personal perspectives and experiences rather than universal truths

- Identifying shared values and imagining better futures together (whanaungatanga)

- Naming barriers that prevent us from reaching that future

By using this method, I immediately noticed the different paths dialogues could take compared to the more hostile routes I saw others on Facebook taking. People became much more receptive to new ways of thinking (and even inclined to admissions of racism) when they fundamentally felt that their personal circumstances were being considered.

In practice, this often started with an open and genuinely curious question about the views they were presenting, to prompt them to explain the background to their comments. Typical questions were: “What experience led you to believe this?” or, “What do you mean by…?” These kinds of questions, based on curiosity rather than judgement, had the effect of lowering the heightened emotional state of the person, making dialogue possible.

Political Scientist Emily Beausoleil describes the way listening is virtually physiologically impossible during a fight-or-flight response, and that asking some simple questions will bring a person down from this level.

Political Scientist Emily Beausoleil describes the way listening is virtually physiologically impossible during a fight-or-flight response, and that asking some simple questions will bring a person down from this level. However, the problem many tauiwi have encountered with this kind of empathetic questioning, is it sometimes feels like endorsement. Asking, “What do you mean by ‘the average kiwi’?” reveals the racist undertones of this statement (the commenter of course meant Pākehā) but it also prompts them to plainly state those thinly veiled racist thoughts. It is thus necessary to quickly follow up with a counter narrative: “It sounds like we have had very different experiences. My own experience has led me to believe…”, or “I believe that everyone deserves [access to housing/education, safety, etc.], don’t you?” Keeping these statements personal avoids a condescending tone that alienates and blocks the possibility of further dialogue.

I want to stress here that this way of engagement is not applicable to all comments. Some are just downright hate speech, and these should be shut down.

This ‘condescending tone’ I mention is dangerous for us Pākehā to slip into, as it assumes the existence of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Pākehā, i.e. racist and non-racist ones. To elaborate on the definition of racism I offered earlier, I have been brought up to understand racism as discrete acts of violence (verbal or physical), which allows us to define ourselves in opposition to others we label as ‘racist’. In other words, if I don’t commit verbal or physical racial violence, I believe I’m not racist and, therefore, I absolve myself of the responsibility for constantly challenging my privilege. As a Pākehā person, I cannot help but be a member of a colonial system that supports racist comments on Facebook. Even if I never knowingly post racist comments, I am part of a system that allows the comments to exist and, therefore, I have a positive obligation to challenge the comments.

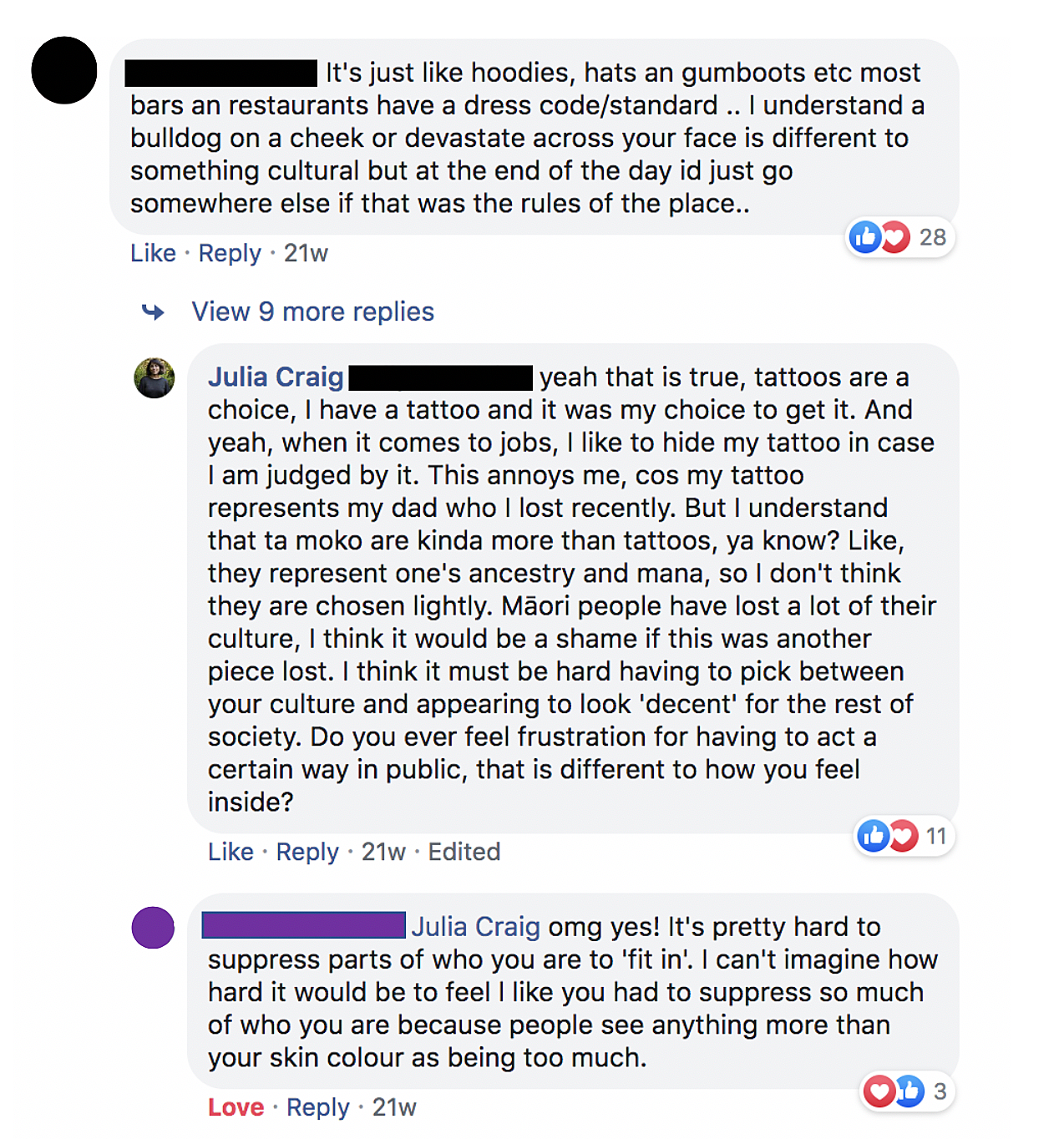

Here's a brief interaction I had with someone under a Stuff article titled "Man with tā moko turned away from Melbourne restaurant":

Although we never actually had a back-and-forth dialogue, I considered this a win because they ‘hearted’ my post. I have to assume the love reaction meant they supported at least some of my comments. Before the Tauiwi Tautoko training, my response to their comment would have been much more defamatory, labelling them racist and accused them of white privilege. I probably wouldn’t have been wrong, but would it have got us anywhere?

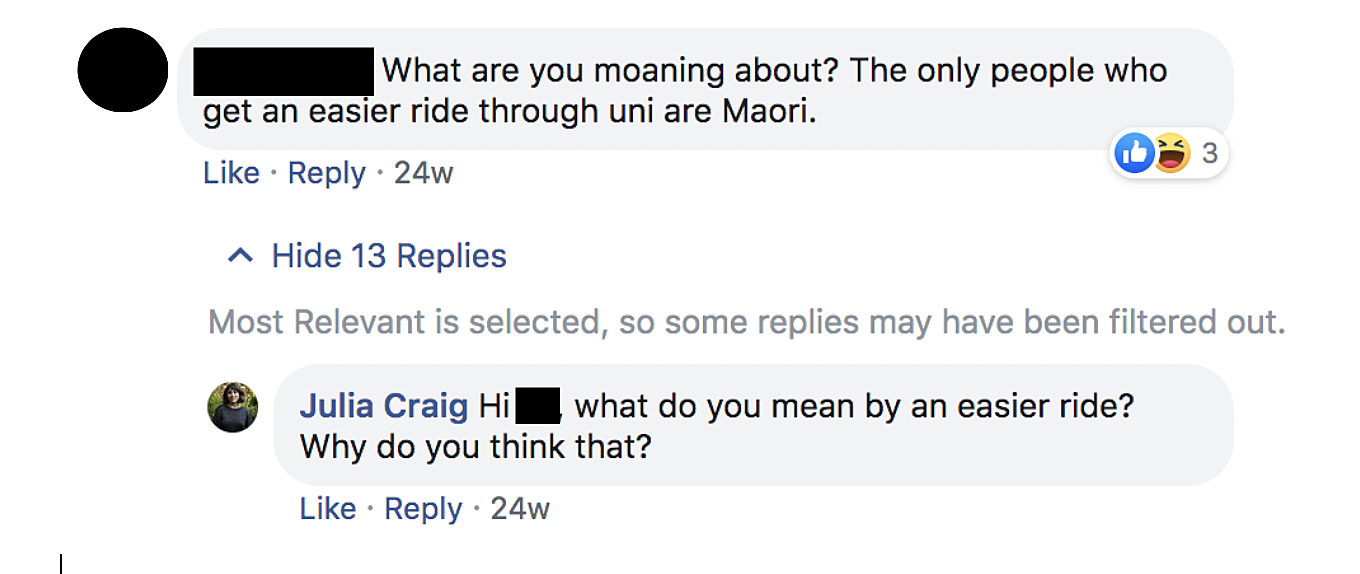

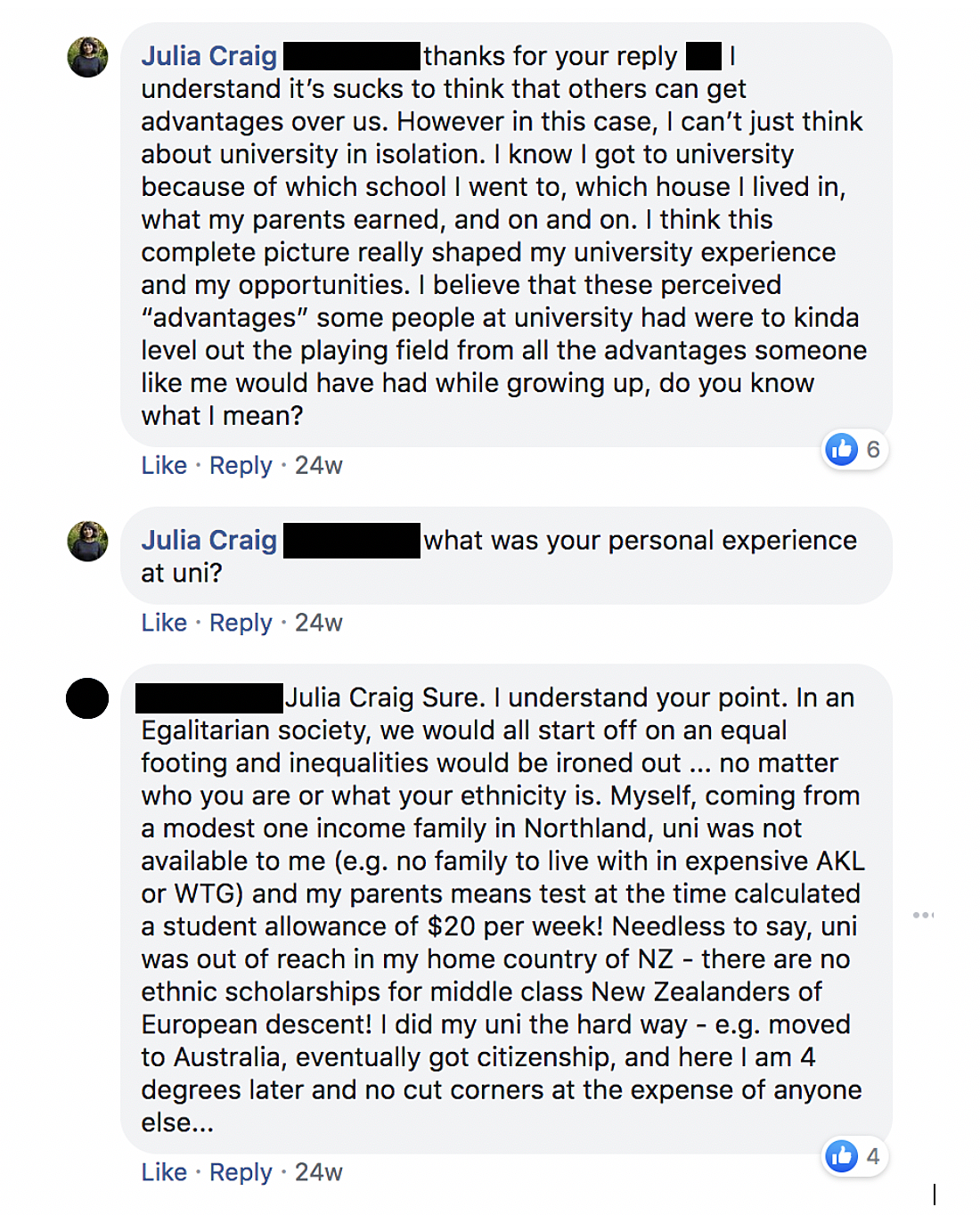

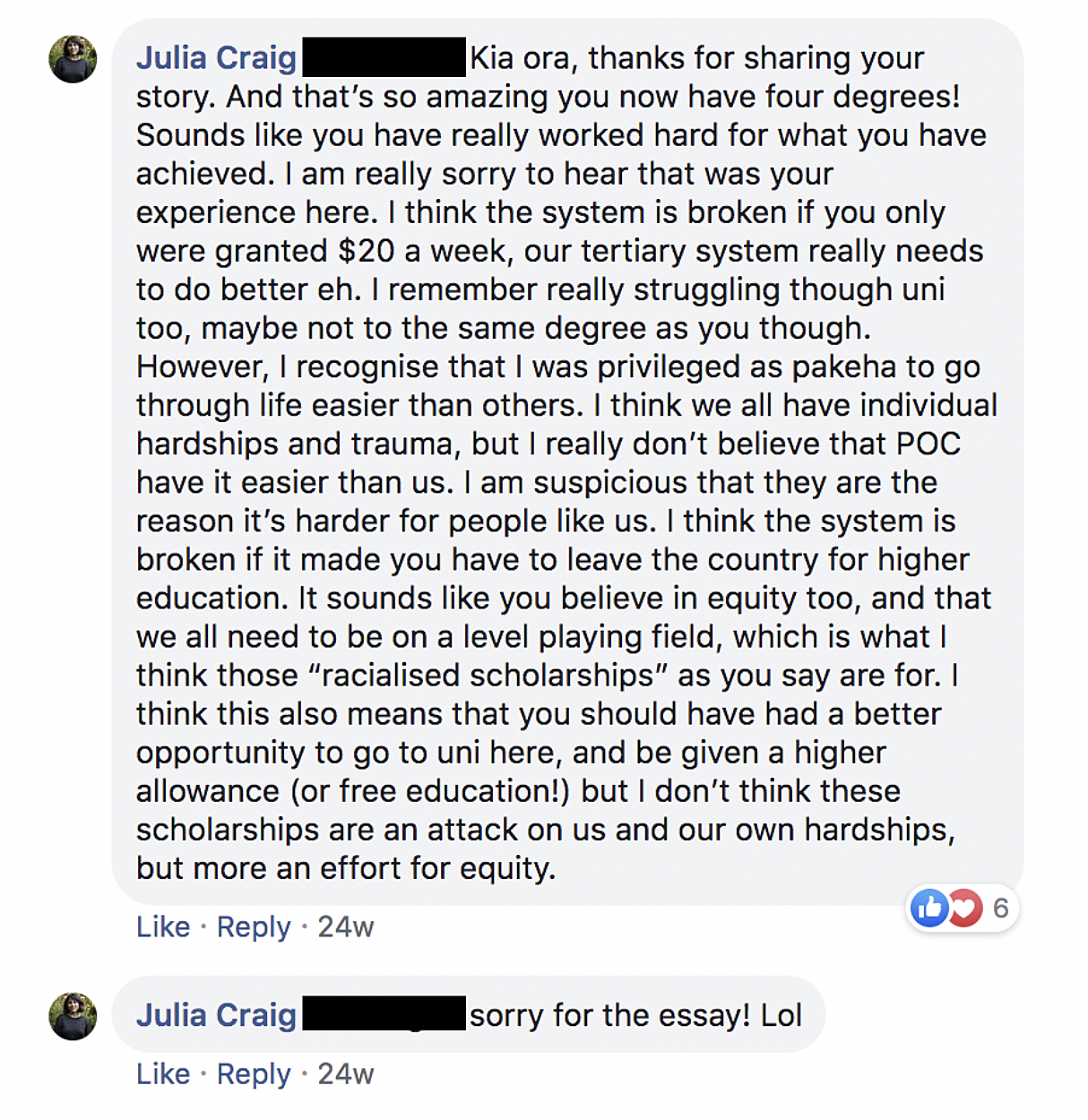

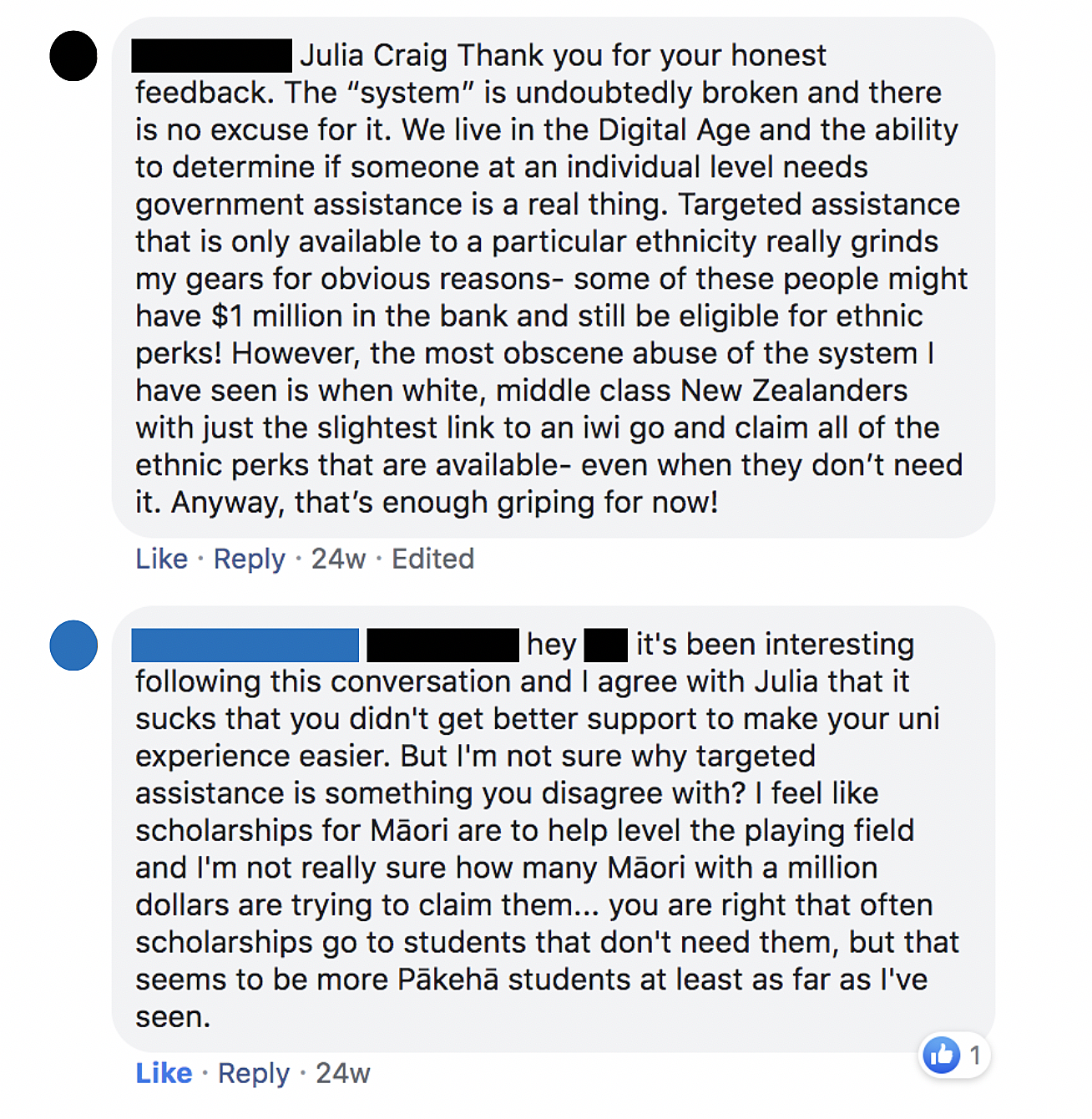

Here’s an example of a more meaty exchange, under an opinion piece by Lana Lopesi for Stuff, titled “If students feel tokenised, it's no wonder there's a lack of Pasifika professors” (some of the messages have since been deleted, so here’s what’s left of the conversation):

Although the article has nothing to do with Māori, this person still found a way to attack them. This relates back to that statistic I first quoted you, that one in three Māori experience abuse online. This is perhaps because some people can find any excuse to take an anti-Māori stance. It continued:

This exchange is a good example of someone’s personal experience shaping their worldview – and overriding any other expert knowledge or objective reality. If someone believes we are all born the same, and should be treated equally then we cannot easily change these deep-held views. They are supported by, among many things, the lack of any colonial history taught in schools, and the belief that Aotearoa has the “best race relations in the world”. They are, therefore, hard to shift, so we need to need to be persuasive.

And that is where it ended. This one did not feel much like a ‘win’. Although we managed to have a civil conversation, I doubt I shifted their mindset much. However, the Tauiwi Tautoko programme would argue that with every person commenting there are a hundred others silently reading. These silent readers are the true target audience of Tauiwi Tautoko. If we leave these comments unchallenged, we reinforce the status quo. You may only move an inch in a one-on-one exchange, but ideally we can inject Facebook with enough compassion and support that racist remarks will no longer be the norm.

I want to be clear that I think anger is a completely valid response to comments like these. The communities being targeted by this racist rhetoric have every right to access the full spectrum of emotions. As Pākehā, we can intervene and have courageous conversations with our own communities because, as Laura O’Connell Rapira aptly explained to me, “you shouldn't have to both experience systemic racism and stand up for yourself.”

At the 2019 ST PAUL St Curatorial Symposium, Professor Alison Jones and Dr Te Kawehau Hoskins from Te Puna Wānanga described the Pākehā relationship with Māori as a journey with no destination. Our learning is never complete – we must commit to lifelong engagement to become better treaty partners. Although Tauiwi Tautoko is about being better treaty partners, it is only one small part of a decolonising kaupapa and is best done in tandem with other forms of activism.

In her book White Fragility, DiAngelo argues that “white progressives cause the most daily damage to people of colour” because they believe they aren’t racist, that they’re ‘woke’ and are thus safe for people of colour. So if these people are ever challenged, they become the most defensive. Their sense of self and their belief that they are a good person (as opposed to a bad, conservative one) is challenged, and they need to do everything to prove otherwise.

The most difficult part of intervening in the comment sections has been resisting the temptation to fact-check and myth-bust. Research shows that fact-checking someone (and especially spell-checking someone) will do little to change their mind. In A Matter of Fact: Talking Truth in a Post-Truth World, Jess Berentson-Shaw challenges the assumption that if we “plug a knowledge gap” people’s beliefs and actions will align accordingly. On the contrary, people will overwhelmingly listen to their values, feelings, and personal experiences as a guide for understanding the world, and these together become a fixed and rigid reality that can diverge significantly from evidence-based research. We can instead try to appeal to a set of values that may be helpful to our cause (and smuggle in some evidence in the process). For example, if someone expresses animosity to refugees and references the housing crisis as an excuse for their xenophobia (I have come across a few examples of this), we can actively listen to what’s beneath the statement, which might reveal a concern for a lack of housing in Aotearoa, and can then appeal to the shared value that everyone deserves a place to live.

One person’s shameful racist comment is also our shame, so let’s ease the burden for our minority communities and have some courageous conversations.

As much as they would like to claim objectivity, journalists are not immune to unconscious bias, and it's easy to find examples of this in action. I would go on to argue there are a lot of instances when some media outlets seem to be deliberately racially provocative to get more engagement on Facebook. This is just one reason the comment sections become such a hub for racist and hateful rhetoric. In order to remain competitive, platforms like Stuff NZ are pumping out as much clickable (i.e. provocative) content as they can, with fewer staff to moderate the public’s comments. Facebook, on the other hand, does have the resources to more effectively moderate misinformation on their platform. ActionStation has recently presented a petition to Parliament calling for the faster removal of harmful content, and to prohibit this content from benefiting from Facebook’s algorithms that propagate such polarising messaging.

Even if we find the courage to spray the comment sections of Stuff and the New Zealand Herald with positivity, I’m under no illusion that we’re going to dismantle racism. We could, however, change the atmosphere of our digital spaces. If we flood Facebook with supportive, balanced, and evidence-based comments, perhaps one day that will be the norm, and others won’t feel so emboldened to attack minority groups. In the time of Covid-19, when our Asian communities feel less safe, we (Pākehā) must take responsibility for this unacceptable reality we have created. As members of the dominant group, all spaces belong to and are controlled by Pākehā, and that includes online spaces. If online spaces are unsafe for minority groups, that’s because Pākehā people allow it. It is, therefore, our duty to make all spaces safer, kinder and better-informed. One person’s shameful racist comment is also our shame, so let’s ease the burden for our minority communities and have some courageous conversations.

Header image by Markus Spiske on Unsplash