Love Letters to the Critic I

With paid critics threatening to go the way of the Haast's, here are a few reasons why you should care.

“Reviewing is not really a respectable occupation” – W. H. Auden

Let’s say we’re in a theatre. The lighting onstage casts the front row in a warm amber wash, and as we pan across the audience we catch the captivated expressions on each person’s face, the occasional mouth hanging open in muted awe. Then we reach the end of the row. Here, we find a figure in a dark coat, hunched over their seat, scribbling blindly into a notebook. When they finally look up, their face is expressionless. Bored, even. Yes. Who else but the critic, that joyless, thin-lipped dick.

But it should come as no surprise: The critic gets a raw deal. Rarely appreciated, they’re the pariahs of the creative industries, exasperatingly vocal audience members whose contributions are rarely considered as valuable as those of whom they critique. And it’s not just artists who undervalue them: it’s those who read them (or don’t) and their employers, too. This year has been a tough one for mainstream criticism, with two standout blows marking the months: First was APN’s decision in April to kill Volume, a street-press publication that brought together some of the greatest young voices in music criticism in this country (full disclosure: I consider fellow Pantograph Puncher Joe Nunweek to be one of them) and more recently was Sunday Star Times’ decision to disestablish the role of Culture Editor and fold it into the ‘Escape’ section.

Given the results of Creative New Zealand’s recent report on public engagement with the arts – with 85% of the population attending a cultural event in the past year and spending an average of $53 a month (coming to a total of $2.31 billion over a twelve-month period) – this suggests that there’s a gap in having an interest in the arts and having an interest in reading about the arts. There’ll be myriad reasons for this gap, but one of the main ones is surely the reciprocal relationship between engagement and quality. In other words: (a) there’s low engagement with criticism in the first place and (b) little motivation to engage more.

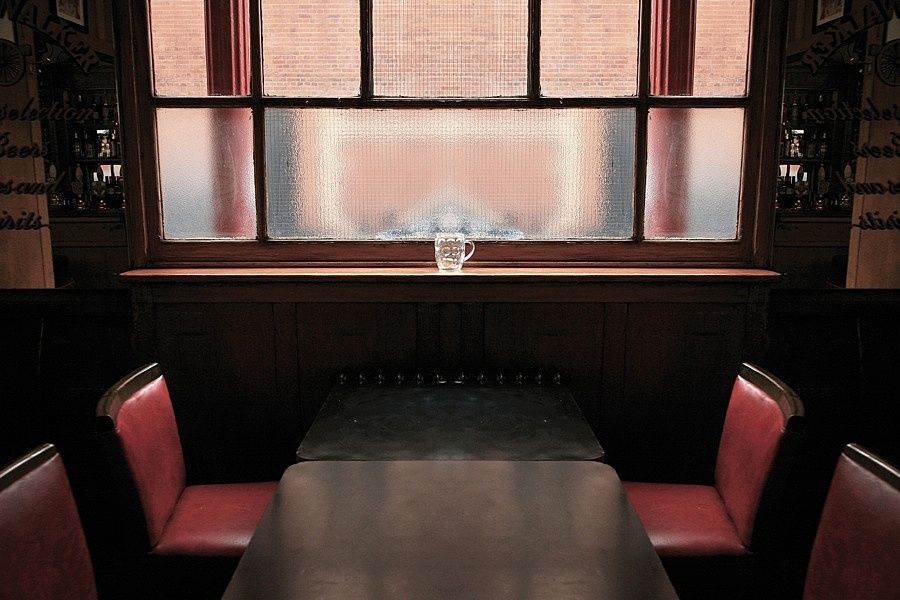

This kills me – like, actually gives me a twinge in the pit of my belly. It’s like watching a couple have dinner in a restaurant where the only sounds they emit over the course of fifty minutes are the clinking of cutlery and a tweet being favourited. It’s painful and it’s punishing, and all you want is for them to see what they’re doing to each other, but maybe it’s not your place to say.

In this case, it is: We need critics. I don’t mean this in the royal sense, or even in the editorial sense. We – all of us – need critics. They’re a filter. They help us decide whether it’d be better to buy the new Justin Bieber or to enjoy being a functioning adult. They articulate their experiences in ways that are equally as exciting as the work itself, and sometimes more so. They stand on the shoulders of giants, or at least they’re clambering up their backs, and so they write with expertise. They can track broad trends and movements in ways that we can’t or don’t. And they’re passionate – truly passionate – about books or film or theatre or music and hold it to a standard that’s higher than whether it simply entertains. For artists, this makes them a source of constructive feedback. This also makes them a gateway to a more meaningful dialogue, and it’s only through this that we can make progress. We need critics. But it’s hard work being one, and in a country like New Zealand, it’s near impossible.

Nobody Likes a Critic - But They Should

“Sting... Sting would be another person who’s a hero.

The music he’s created over the years – I don’t really listen to it.

But the fact that he’s making it? I respect that.” – Hansel, Zoolander

We’ve all seen it: somebody writes a negative review and the person being reviewed lashes out. Typical responses: what have you ever done, I thought we were friends, whatever, everyone else loved it and you’re a contrarian bitch.

In some instances the artist will go one further – Opensouls, for example. When Duncan Greive wrote a damning hundred-word review of their performance at the 2003 bFM Summer Series, they responded with the "The Critic", a song that names and shames him in vaguely threatening ways (see Part II for our conversation with Greive and Chip Matthews, the bassist for the now-defunct band).

There are three beliefs that underlie responses like this:

- That someone who creates deserves a basic modicum of respect;

- That negative reviews are unsupportive; and

- A critic should be a voice of the people.

Number one I absolutely support. Apart from childbirth and sex, sharing something you’ve made is the most intimate act you can engage in with another person. When you’ve created a work with sincerity and care, and when you’ve created it for yourself and not somebody else, that’s your soul on the page, or the stage, and if it’s not, you’re not doing art. You’re doing advertising or crafts and calling it something else

Two is where things get dangerous. It’s not an entirely illogical step to take from One. You’re making yourself vulnerable, and when someone slams your expression of that, the response is physical – a cold crawling that starts in your gut and shivers its way across your body. It’s your every insecurity coming into play. Look, if there were a God, the reason we haven’t had a rapture is because He doesn’t want the bad review. We know the pitfalls of our own work. It’s not that a well-written negative review is unfair: it’s that it systematically and stylishly lays those pitfalls out for everyone to see. It’s ultimate humiliation, and it does feel unsupportive, but that doesn’t mean it is.

There is a delicate balance to be struck, though. Take Dale Peck, the bad boy of the New York literati who famously began a review of Rick Moody’s The Black Veil with “Rick Moody is the worst writer of his generation.” In 2004, Stanley Crouch approached him in a crowded restaurant and bitch-slapped him, saying, “If you ever do anything like that again, it’ll be much worse.” Presumably this was in response to a review Peck had written three years earlier of Crouch’s Don’t The Moon Look Lonesome, which he described as “a terrible novel, badly conceived, badly executed, and put forward in bad faith... in response to the question in the novel's title, one wants to answer "No," simply, wearily, but also sternly. "It doesn't."

Mostly I stand by Peck’s right to be mean – his “scorched-earth policy” as novelist Jeffrey Eugenides once called it – because it comes from someone who is fiercely passionate about books and can speak intelligently about them, and because there’s something fundamentally entertaining about watching someone get this outraged over a novel (it’s just a book, mate: chill out).

My official line is that critics like Peck are valuable because they encourage discussion around the work and the form, though when I suggested this with self-satisfied gusto to Fergus Barrowman, editor at Victoria University Press, he hesitated. “I don’t think it’s entirely to our credit that we enjoy vicious reviews as much as we do,” he said, “but we do. I suspect talk about stimulating the wider discussion is a bit of a figleaf.” After a telling moment of indignation, I realised he was right – nasty reviews make for better reading. Bad experiences are funnier than mediocre ones and reading about them gives us voyeuristic pleasure. It takes an existing level of engagement to look beyond the entertainment value of a review like that and discuss the work itself.

Cruel reviews aren’t exactly common in New Zealand, though, particularly when it comes to reviewing New Zealand artists. As Barrowman points out, “Mean reviews really hurt writers, and because we live in such a small community the writers of those reviews quickly get to hear of the emotional harm they’ve caused. That’s why a lot of writers won’t review: they don’t want to be dishonest, and they’re not callous enough to be honest.”

These are unfortunate truths. We’re a nation bounded by two degrees of separation and desperate to avoid confrontation. It’s inevitable that someone will consider a negative review unsupportive, but if this means creating a placid environment where the ability to have an open dialogue is stifled, surely we’re missing the point.

At its heart, a review is about holding an artist accountable, in the same way a journalist might hold a politician accountable. Artists are asking you to sacrifice your dollars and your time, and if they’re claiming to do something (for instance, tell a compelling story) and they’re not, someone should say so. This ties in with the other crucial role a reviewer plays: facilitating commentary around a work in a way that serves both audience and artist. Without this system in place, we’ll get cultural anarchy: a reckless and careless industry that lacks the scaffolding to propel it forward.

It’s important to remember that most critics don’t go out of their way to write a negative review. They’re in the position they’re in because they love the form, and the most rewarding part of their job lies in the discovery of something new, and having the opportunity to champion that something and give it an audience it might not have received otherwise. That’s the money shot. A negative review, rather than being vindictive, comes from the pained observation that something isn’t reaching its potential or worse, isn’t even trying. Critics are those weird fans that show up at marathons with plastic cups of electrolyte-infused water for their favourite runner – the kind who get inexplicably emotional when that runner comes in three minutes below their time.

As for the third point – I’m not sure it warrants discussion, despite the fact it’s one of the most common responses to a negative review. Critics have to be accessible to the public, but they should speak to where art has the potential to go, rather than where the populous (and profit-driven commissions) want to take it. Someone’s got to maintain some semblance of artistic integrity, right?

The Democratisation of Criticism

Though many would say otherwise, art simply cannot thrive in this environment. It’s toxic. It devolves reviews into bland recommendations peppered with the occasional minor quibble. Negative comments become so codified in euphemism that they’re rendered not only worthless but misleading – a play that’s incomprehensible and dull becomes ‘experimental’ with ‘moments of brilliance’. Reviews become peacemaking by nature, causing readers to lose interest and their employers to value them less. Critics are given fewer dedicated pages. They suffer ruthless pay cuts.

Exeunt: Excellent writers who have no motivation to keep writing, apart from their love of the form (hint: this isn’t enough, not even with an unhealthy dose of idealism).

Enter: Average writers doing it for the wrong reasons and good writers who can only put in as much time and effort as their pay will allow, i.e. not much.

Scene: An escalating cycle of declining quality and value, with bland and toadyish recommendations cultivating expectations of mediocrity. Lazy reviews that serve only marketing departments instead of everyone that it actually should.

Now, lazy reviews: This is the worst. This is what’s unsupportive. If you are going to review something that is ‘so good you can’t find the words to do it justice’, then why the fuck are you doing it in the first place? You are wasting everybody’s time. There is zero benefit to be gained from giving us a summary of the plot, an unblinking slew of platitudes, and a sycophantic urge to buy this album/see this play/read this book/watch this film. Nor is there any value in being the Garth George of reviewing – don’t revel in your own crotchety ways. Be inspired by art, not by yourself. Neil Kulkarni puts it best when he laments the decline in music criticism, saying:

It reads as if music writing is actually a painful, unpleasant process for those doing it, the annoying production of actual stuff that unfortunately is still attached to the real job of connecting, networking, partying and self-promoting. These are writers surely inspired by no one, and consequently it’s impossible to hear a human voice emerging, or see an effort involved in finding that voice... Where is the writing that speaks across to the readership, across the table, across the room, across the tracks and divisions to illuminate new ideas? Spiked, knocked out, or worse – not even thought of anymore. Reason? Because the WRONG FKN PEOPLE want to be music journalists, beavering hustlers and networkers, passionate ambassadors for their own needy inclusion in da biz, people so damn obsessed with getting their foot in the door they haven’t figured out if they have anything more than fuck-all to say, and couldn’t care less how revoltingly commonplace is the way they express that fuck-all. Style-less automatons of triteness and humbug and horseshit that criminally WASTE your time, and don’t even give you a laff in doing so.

But this is what we’re enabling: mindless and lazy ways of engaging with art. With fewer paid positions, we’re seeing an explosion of bloggers whose only reward for writing a review are tickets to the opening night of a show, where they rub shoulders with C-grade celebs and knock back glass after glass of champagne, all of which are provided courtesy of the production company - and they’re hardly going to bite the hand that feeds. We’re building a false economy of enthusiastic reviewers, satisfied production houses and a public who don’t know any better.

I’m not saying these writers don’t have the chops to write good criticism. Most of them probably do. I’m saying there’s no reason for them to do it. There are scores of good critics out there, though most will be found in American pages – Zadie Smith, Elif Batuman, Marco Roth, James Wood. We have good critics in this country, too, but a lot of them have stopped writing because their talents are better rewarded elsewhere. YOU GUYS. We need the Duncan Greives and Joe Nunweeks and Jolisa Gracewoods and Janet McAllisters of this country. We need people who are intelligent, who still experience art with breathless wonder but who are discerning enough to write about it with a critical eye. But if the only thing we reward are people writing safe recommendations focusing on the kind of minutiae that benefit noone, or bloggers who are clearly inspired not by art but by themselves, and who revel in the kind of cynicism that is neither intelligent nor attractive, then don’t be surprised – and don’t you dare complain – when this is all that we get.