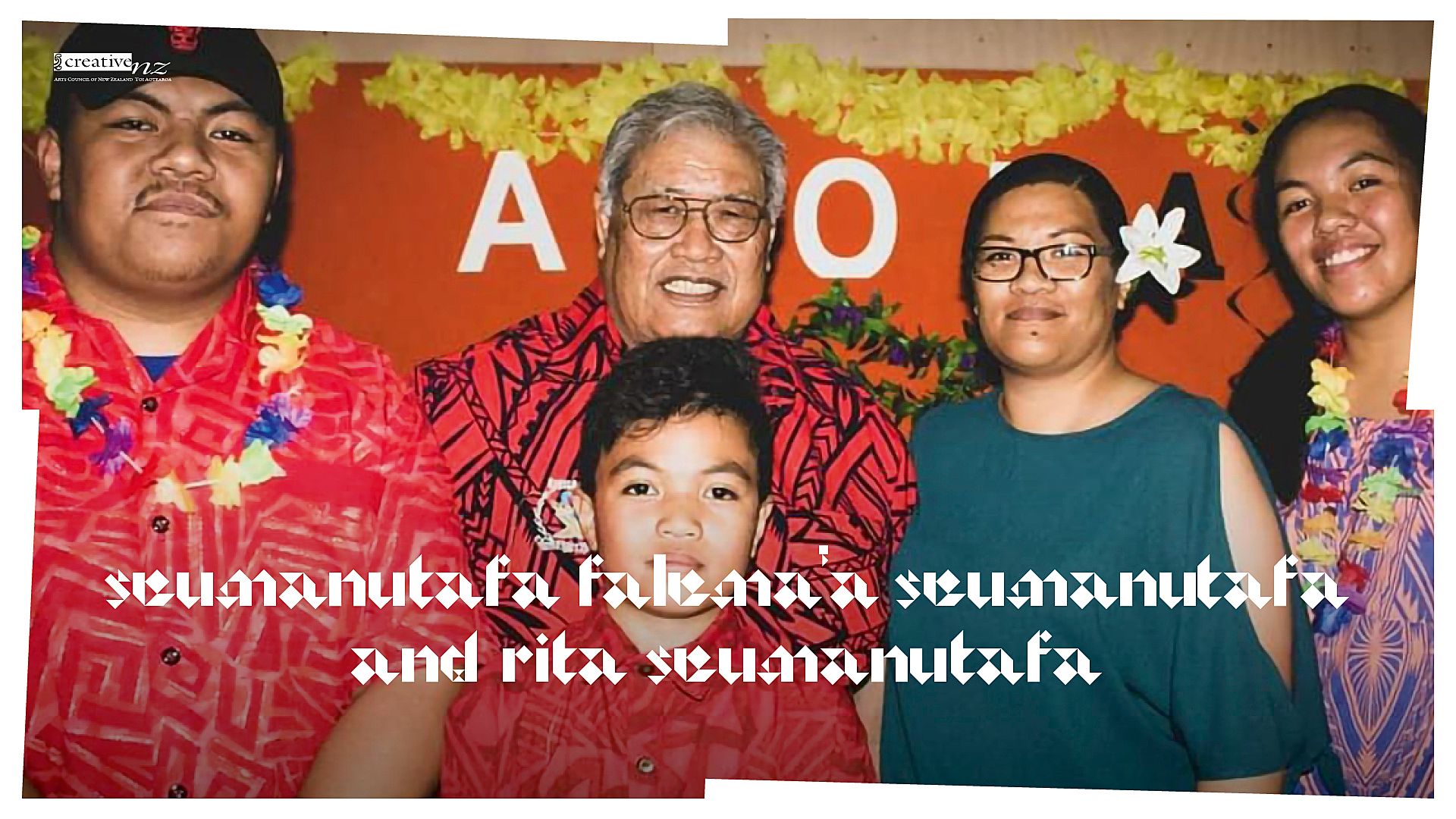

From Savai‘i to Tāmaki Makaurau to Melbourne: A Legacy of Love, Faith and Music

“Let the world know what it took.” Rita Seumanutafa and her father Seumanutafa Falema‘a Seumanutafa share the legacy of their music.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the ground-breaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Lagi-Maama Academy & Consultancy first met Rita in early 2019 when we were invited to be part of Te Pasifika Exhibition Advisory Group with Melbourne Museum for the redevelopment of their Te Pasifika Gallery. Rita was one of the researchers for the exhibition redevelopment team. During our talanoa she shared about her life in Aotearoa, the move to Melbourne and her PhD studies in ethnomusicology. Fast forward to 2022, Lagi-Maama is excited to be working in collaboration with Rita as part of a CNZ funded project called Fāgogo and Fananga – Untapped Knowledge of our Ancestors where we are engaging her knowledge and expertise as an ethnomusicologist. Her musical gifts were predestined well before this time and space and have been lovingly nurtured by her aiga, her beloved communities and driven by her father Seumanutafa’s tautua to God and community.

Dad’s Story — Seumanutafa Falema‘a Seumanutafa

I was 30 years old when I moved to New Zealand on 10 October 1974. It was a rushed, short two days of preparation to get here. I found out about the opportunity to move while I was working in a plantation in Savai‘i, my island of birth. My name was called out over the radio, announcing that I had mail waiting for me at the Samoa Post Office in Upolu. I left the plantation that day and went home to Sasina, where my mother was waiting for me. She listens to the radio all day and confirmed that my name had indeed been called out and that I must hurry to Apia, on the main island, to retrieve my mail.

I had never received mail before, so my mother and I were curious to find out what was sent to me. The next morning, I caught the ferry to Upolu, and headed straight to the post office in town. It was a telegram, a message with a request that I join a new band in Papakura, Auckland, as they were in need of a lead guitarist, and I was recommended to them. I took the message back to Sasina to discuss with my mother, who gave me her blessing to take this opportunity and start a new life in New Zealand. I prepared for my departure the next day.

Seumanutafa posing next to his choir instruments at East Tāmaki CCCS (Congregational Christian Church of Sāmoa), Auckland, 2014. Photo: T Tuia

Seumanutafa leading the East Tāmaki CCCS choir during Sunday worship service, Auckland, 2014. Photo: T Tuia

Seumanutafa with his grandson Jeramyah at East Tāmaki CCCS, Auckland, 2014. Photo: R Seumanutafa

My life in New Zealand was good, and I enjoyed the opportunities given to me as a young, single man. I stayed in a house in Ōtāhuhu with 15 or so other Samoans, and there were two houses next door just like ours, and each with the same number of people. So in total there were about 45 of us. We lived together as a village, with all three houses being supervised by Reverend Kalati Perese and his wife, who helped us to find jobs and to send money back home to our families in Samoa. It was only a few short months before the news broke that anyone who had overstayed their working visa was being found and instantly deported back to the islands – that meant our whole three houses of people could be deported at any time. Therefore, our village in Ōtāhuhu was strictly supervised by Reverend Perese, who reminded us every day of our conduct when out and about. We were not allowed to go anywhere other than to our daily jobs, we were not allowed to talk to anyone while making our way to and from work, and we were especially not allowed to discuss our visa status with anyone. These rules helped to keep us from being found by the police and to keep us all together. We all knew how important our lives in New Zealand were for our families back in the islands, so we agreed to abide by the rules. We had lotu (prayers) every evening in one house, while the other house had a large kitchen where our evening meal was being prepared.

We were not allowed to go anywhere other than to our daily jobs, we were not allowed to talk to anyone while making our way to and from work, and we were especially not allowed to discuss our visa status with anyone.

I began a new job at a factory nearby in Mt Wellington. I had only been working there for a few weeks when my supervisor, a Pālagi man, asked me if I was interested in staying back to work overtime. I was surprised to be offered overtime that day, as my Samoan workmates told me that overtime was only given to those who had worked for at least six months at the factory. Before I could accept his offer, I had to ring home to get permission from Reverend Perese and his wife, as finishing late that evening would mean breaking my curfew. Once they agreed to it, I stayed back and worked the overtime shift.

Later that evening, I walked home, taking my usual Panama Road route to Ōtāhuhu. As I neared home, I saw police vans pulling up to a red light close to where I was walking. In each van, I saw familiar faces looking back at me – it was everyone from the three houses. They looked so sad, their wide eyes telling me to run. I got so nervous and felt scared. I knew at that moment that the police officers in the vans were looking at me and probably wondering if I was an overstayer too. I made a quick decision to walk up to the nearest house, stop at the letterbox and pretend to check the mail, then walk up the path to the front steps to sit down and start taking my shoes off. I heard the vans moving, so I looked up and they were driving away. I quickly put my shoes back on, then stood up and ran home as fast as I could. When I got there, one of the girls was standing in the kitchen of the main house, turning off the ovens as the large pots of pig trotters were still boiling away on the stovetops. I asked her what happened, and she told me that the police had barged into the house where everyone was having family lotu. She was in tears as she described what happened – the police had carried Reverend Perese out while he was standing, mid-prayer – two police officers grabbed him by each arm and lifted him up and into the vans while he kept his eyes closed and kept praying. People were screaming and crying as the police took them all. She told me to pack my suitcase and get out of there before they came back looking for anyone left behind.

Within a few minutes, I was on my way, walking down the street in search of my aunty Salu’s house. She would help keep me safe and, when the time was right, help me apply for citizenship.

I was so scared. I didn’t know what to do or who to turn to. Then I remembered that I had a relative, my aunty Salu, from Sasina, who had moved to Auckland before I did. I had been to her house once, but I couldn’t remember how to get there. Within a few minutes, I was on my way, walking down the street in search of my aunty Salu’s house. She would help keep me safe and, when the time was right, help me apply for citizenship. I walked through the streets of Ōtāhuhu, carrying my suitcase in one hand and in the other hand, a plate of pig trotters to eat on the journey. It was dark outside, so I was careful to walk when traffic was light on the road, ready to hide in whatever front yard I happened to be passing if I saw a police car approaching. I couldn’t remember Aunty Salu’s address but I had an idea of what direction to walk and what suburb her house was in. Ōtara was at the other end of Ōtāhuhu so I made my way there and prayed to God that I would get to her place safely and without any trouble from the police. I had been walking for a while, still confused as to what street I should walk down and if I was heading in the right direction with each turn, when a taxi driver pulled up next to me. This kind Indian driver wound down his window and told me to get in – he had passed me a few times while driving passengers and wanted to help me get to my destination. I told him I was sorry I had no money to pay him, and no address to give him. He told me it was okay as he wanted to help. He could tell that I was trying to hide while walking on the street, so I hopped into his taxi and we drove around the streets of Ōtara looking for a familiar street. We drove around for maybe an hour before I finally recognised a street to turn into and, from there, we found Aunty Salu’s house.

I believe that God saved me that night. So I made a promise to Him that I would leave my band life and, instead, use my musical gift for lotu (church).

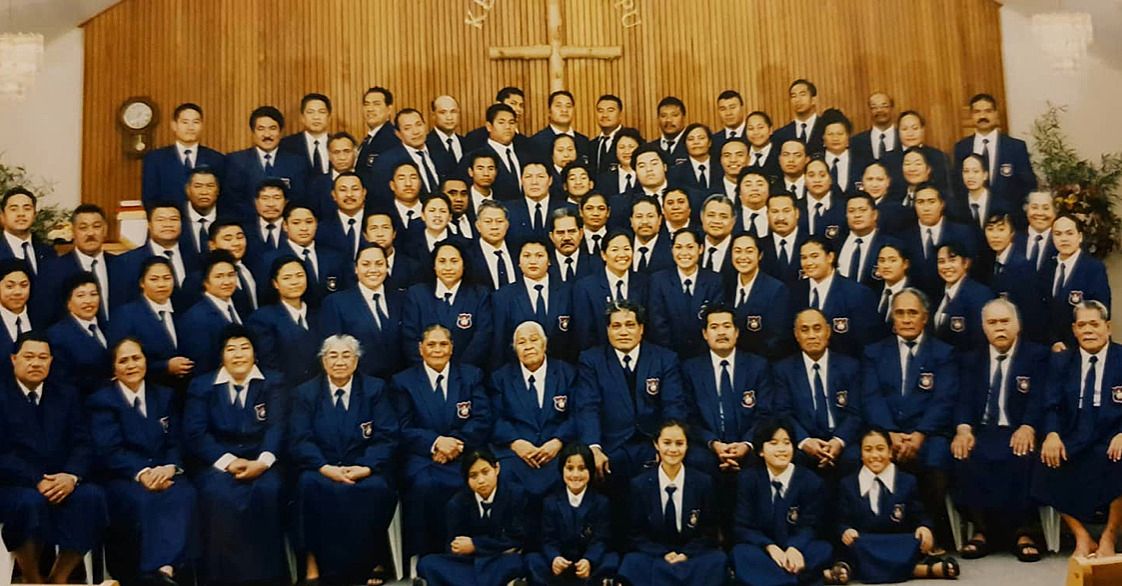

East Tāmaki CCCS choir, featuring both Seumanutafa Falema‘a (fourth row) and Rita (second row). At this time, the congregation was led by Reverend Dr Peniamina Vai (front row) and his faletua, Rosalina, Auckland, 2001. Photo: K Vai

A few years passed, the police search for overstayers came to an end and I was able to apply for my New Zealand citizenship, which I did as soon as I was able to. I enjoyed my job as a welder and tried to learn how to speak English so that I could understand everyone.

In the late 1970s, I got married to Fia Akenese Sola and we had three children – our son Ageli (who we named after Aunty Salu’s father) and our two daughters, Rita and Faaiu. I worked hard to provide for my family, and in 1979 we built our house in Ōtara. I continued to make a good life for myself and my family, and started bringing over my relatives from Samoa, helping them to settle here and start their own families too.

Left to right: Fia Akenese Sola, Seumanutafa (standing) and Rita in the back row and kneeling in front is Ageli with Faaiu on the right, Auckland, 1998.

As a church musician, I spent the first 10 years in New Zealand playing piano for different church choirs – from Manurewa Samoan Methodist Church, to Weymouth Congregational Christian Church of Samoa, to becoming one of six founding families of East Tāmaki Congregational Christian Church of Samoa (CCCS) in 1985 – I have been the Choir Director of East Tāmaki CCCS for almost 40 years now, and it is a role that I will do until I leave this world. From the early 1990s onwards, I have also mentored many young Samoan church musicians – these are young people who have come to me to develop their church music skills. I have also become a father figure for them, and today they have grown into beautiful adults with their own children. I know that they value the importance of paving the way for their future musicians and I am blessed to have been an influence on their lives too.

East Tāmaki CCCS choir being led by three of Seumanutafa’s mentees – Rita Seumanutafa and Lepa Toleafoa on the organs, and Naomi Stretton conducting, Auckland, 2014. Photo: S Muller

Seumanutafa with one of his music mentees, Naomi Stretton, Auckland, 2017. Photo: N Fruean

One of my biggest blessings in life is seeing my daughter Rita become a well-respected and influential musician for our Samoan community and for Pacific Islanders around the world. She is 43 now and out of all our children, she was the one I spent most of my time with, as she inherited my love for music. I began teaching her basic piano skills when she was a little girl, but that didn’t last very long as I only knew a little bit of music theory and couldn’t teach her more than what I knew. When I think of the years of driving her to piano lessons every week, attending her choir and piano recitals, praying for her before her music exams, my heart is always filled with so much gratitude and pride. Even though there were a few years when she had to find her way back to music, she has grown into a beautiful woman who has inspired many with her love of music, God and community. Today, she knows so much more music than me that I always video call her and ask her for help on whatever pese lotu (church songs) I’m working on. I don’t know how much longer I have on this earth, but I will continue to serve God through music, for my family has been blessed many times over, and I am grateful for that.

Rita Seumanutafa, Melbourne, 2012. Photo: S Marshall

When I think of the years of driving her to piano lessons every week, attending her choir and piano recitals, praying for her before her music exams, my heart is always filled with so much gratitude and pride.

1. Rita’s young piano student Ali Natapu, performing at the Rita’s Music School piano recital, with Rita accompanying him, Melbourne, 2016. Photo: R Seumanutafa 2. Seumanutafa playing pese lotu at home while visiting his Melbourne family, Melbourne, 2019. Photo: R Seumanutafa. 3. Seumanutafa speaking to the young members of St Andrew’s Samoan Youth Choir, sharing encouragement. Seated next to him is his grandson, Jeramyah, Melbourne, 2018. Photo: R Seumanutafa

Rita’s Story — Rita Seumanutafa

According to my father, I was four years old when he noticed my ability to sing pese lotu in tune. I was the middle child of three – the most musical, and the one child who eagerly attended church choir practices with my parents. After every choir practice, I would sing all the way home from the back seat of our car. I sang the songs we just learnt at practice and if we didn’t get home by the time I finished singing them, I would sing them again but in the different voice parts each time. My father was always amazed at how well I memorised choir parts and sang them correctly each time, acapella.

Learning music came naturally to me. Dad was my first keyboard teacher, and taught me everything he could, which consisted of the seven notes of the keyboard and basic note values. We had lessons at home using the old pump organ – the instrument was a little wooden box with an accordion-like sound. To work it, you had to pump the two pedals with your feet and play on the keys at the same time. By the time you finished playing, you would be sweating from all the pedalling. When it was time, my father took me to a piano school – the Auckland School of Music, which was owned by Lenice Frisken. The movie The Sound of Music, which featured beautiful choral music, a pipe organ and the beautiful voices of convent sisters, had an influence in my father’s decision to send me to an older Pālagi lady, who would teach me music ‘the right way’.

Rita Seumanutafa’s music teacher Lenice Frisken. Source https://www.facebook.com/lenice.co.nz

My first years of formal music education showed me a different world of music. My aural skills were well developed thanks to my life of singing and learning songs by ear. However, through piano lessons, I had to learn music ‘properly’, as Dad would say, so I wasn’t allowed to play by ear, I had to read music off the paper. I didn’t agree with this so I secretly played songs by ear when Dad wasn’t around. He had dreams of me becoming a music professor one day and leading the church choir. Instead of piano, he insisted that I learn the electronic organ, as that was the principal instrument for Samoan church choirs.

I was still a beginner student when he insisted that instead of learning songs from student piano books, I should be learning the Salamo or Psalm pieces that our church choir sang for the big combined services. I remember one piano lesson where I sat at the organ as Lenice explained to Dad that, because I was a Grade 1 student at that time (beginner level), she felt it was unfair for me to have to learn the Salamo that Dad gave her, as the pieces were Grade 5 level and beyond. I can still remember Dad’s reply to her each time: “No, my daughter can still learn it.” In his mind, if I just practised the Salamo pieces, I could still champion them – even as a beginner. He was right. My dad also insisted that I meet the benchmark at each music level, so every year I sat practical and theory of music exams, and was examined by the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, and Trinity College – prestigious examination boards from London, England.

People would ask my dad who my piano teacher was and Dad would always recommend Lenice’s school, even making sure that parents got to personally meet her when they visited the school. I noticed a lot of Samoan children enrolling into her school in the late 90s to early 2000s – a few of them are church musicians today – and I believe that Dad played a big part in the rising enrolment numbers from our community during that time. Lenice was an accomplished pianist and educator, and the certificates and qualifications that hung on the wall at her music school proved it. Our power bill could be overdue and our power at risk of disconnection, but Dad would insist that my piano fees be paid first so that I could continue my learning. We lived in Ōtara, but I attended Manurewa High School because it was closer to my music school.

Our power bill could be overdue and our power at risk of disconnection, but Dad would insist that my piano fees be paid first so that I could continue my learning.

As you can imagine, my father had very serious aspirations for my musical life, and training began as soon as I was old enough to handle it. I started playing the organ for church when I was 10 years old, and by the age of 16 I was teaching and conducting the church choir. I also had a part-time job teaching piano students at Lenice’s school. By 19, I began composing pese lotu for Sunday services. For my birthday, Dad bought me a cassette-tape album every year from the age of eight. Sometimes it was Punialava‘a, sometimes it was UB40, then on my 11th birthday my parents bought me my first organ – a Yamaha Electone.

My teen years were spent playing pese lotu for at least one hour every day and sometimes, when Dad wasn’t around, my cousins and I would do our own karaoke from the organ – I would play pop songs from The Carpenters, Jackson 5 and The Sound of Music while they would sing. I wasn’t allowed to study music in high school because Dad didn’t want a high-school teacher messing with the education that I received from Lenice’s school. However, in my final year of high school, Dad let me sit Bursary Music as a subject because the new music teacher, Mr Nigel Weekes, was a professional choir director, and anyone who had this level of expertise in the subject of choral music sat in the category of ‘Lenice’ in my dad’s eyes.

I could speak and engage with music more than I knew my own Samoan language and culture – music literally was my life.

I could speak and engage with music more than I knew my own Samoan language and culture – music literally was my life. As a musician, I knew my place in the community, and as an educated musician and daughter of a devout church musician – especially one so serious as my dad – I knew that my life was a rare one. For 14 years, my weekly music routine was choir practices on Wednesday evening, preparation on Saturday afternoon, and Sunday morning service. During that time, there were also a few short years of music service for the Bible Baptist Church across the road, which added Sunday, Monday and Friday evenings to my music routine. When I look back, I am amazed at myself – how on earth did I get through those years? Also, while others may interpret my life during this time as musically fanatical, I reflect on those years with gratitude and awe. I am so lucky to have lived it.

As I grew older, I wanted to focus on other aspects of life. I got married, had children and moved to Melbourne, Australia. I slowly started to live a life that wasn’t saturated with music. In my first few years of living in Melbourne I couldn’t afford a keyboard, so for the first time in my life I did not own a musical instrument. During this time, I learned more about the Pasefika community here – everyone was so spread out across the outer suburbs, living in small population pockets. You couldn’t walk down the road to your aunty’s house or even walk to church, because ‘down the road’ meant at least a 15-minute drive. The Samoan community was smaller than what I was used to, the church groups were small too, and the people were different. I came from my safe little community in South Auckland where we all knew each other, to a community of different Pasefika people who came from many New Zealand cities.

I got a taste of a somewhat simpler life in those first few years. I was a stay-at-home mum and had no ties to any Samoan church. I guess I started to enjoy the freedom of not having to be responsible for Sunday morning music every weekend. Sleeping in on a Sunday morning, and not thinking about pese lotu on a Saturday afternoon, took some getting used to. However, on my regular phone calls with Mum and Dad, they always reminded me of the gift that I was blessed with, making a point of telling me that my gift was not meant to be kept hidden, and that I needed to share it, so others could be blessed too.

However, on my regular phone calls with Mum and Dad, they always reminded me of the gift that I was blessed with, making a point of telling me that my gift was not meant to be kept hidden, and that I needed to share it, so others could be blessed too.

One day, I felt the call. My return to the choir occurred one Sunday as we attended a new church service. The congregation was smaller than I was used to, and the choir sounded different from the ones back in New Zealand. I sat during the service, not paying much attention to the Reverend at the pulpit because my attention, and all my senses, were tuned in to the small choir. It was hard not to compare this choir to what I grew up with back home, but one thing stuck out for me. There I was, with all these musical skills and knowledge, and here was this choir, singing pese lotu but with no one at the piano. It sat there empty and unused during the entire service, because there was no pianist in this group of worshippers. I was filled with so much conviction and deep shame at that moment. The sacrifices that my parents made for me were going to waste because I was hoarding this gift all to myself. After the service, I went up to the church minister and asked him when the next choir practice was, and so began the end of my sabbatical and the beginning of my best life.

From that moment on, my music ministry became much more than just something for church. Over time I realised that there were many things missing from within the small Pasefika community here in Melbourne – there was no constant platform for cultural learning, engagement and celebration. If you weren’t part of a Pasefika church community, you were missing out. It was sad to see that many of our people here were cut off from opportunities where they could practice culture or even express it. I understood that my upbringing in the Samoan church in South Auckland gave me the skills needed to activate events that would help bring Pasefika music and other creative arts to the front of our community’s minds. So in 2006, and in the years following, I set out to shake things up. I founded Pasefika community groups, choirs and countless initiatives and programmes in order to fill the gaps. My music ministry expanded from the church choir to a wider platform as an ethnomusicologist, community-engagement consultant and change maker. For me, music was the solution to a more connected, healthier and harmonious Pasefika community.

For me, music was the solution to a more connected, healthier and harmonious Pasefika community.

1. Promotion of an upcoming multicultural choir programme hosted by Brimbank City Council, featuring Rita as guest music director, Melbourne, 2017. Photo: PICAA Inc. 2. Rita addressing the audience at the Shepparton Pasifika Festival, Shepparton, 2018. Photo: Know Your Roots Inc.

Rita leading a rehearsal with the ReHavaiki cast, Melbourne, 2017. Photo: PICAA Inc.

1. Rita addressing the audience during a performance by the Pasefika Vitoria Choir, Melbourne, 2018. Photo: City of Monash 2. Rita as keynote speaker at the Festival of Voices event in Hobart, Tasmania, 2019. Photo: PICAA Inc.

I needed more training in order to do all the creative things I planned to do. So I returned to school at the age of 29, armed with two young children and all the confidence I needed to get through university life as a mature student. I found myself thanking my dad at every opportunity – if it wasn’t for his insistence on me sitting those music exams, I would not have qualified for an audition to enter the Bachelor of Music programme. His prayers and constant encouragement got me through from the degrees of bachelor to doctorate.

Today, my dad’s legacy and plans for my musical life have come to fruition in a way that has – if I’m being honest – surprised us both. Today, I am the only Samoan ethnomusicologist in the world researching and studying the traditional village music of our peoples; I am a classically trained pipe organist and I live and breathe Samoan choral music. I am founder and Managing Director of Pacific Island Creative Arts Australia Inc. (PICAA); I also run a community-engagement organisation called VASA Consultancy; I use YouTube to share pese lotu with fellow Samoan church musicians around the world; I musically direct our CCCS Northgate choir and the Pasefika Vitoria Choir. These opportunities, and the life that my family enjoys today, are from the sweat and prayers of my parents.

I am the only Samoan ethnomusicologist in the world researching and studying the traditional village music of our peoples

I sometimes bump into community elders who know of my dad, and they always comment on how wonderful it is to see his commitment to music and his hard work manifested in the life that I’m living here in Australia. I love to reflect and share my dad’s story with those who want to listen. His story always holds me accountable as a mum today – so that I remember to recognise the natural skills and passions in my own children and do all that I can to help them develop these. There are many stories similar to mine that have not been told, so if you’re reading this and you recognise yourself in our story, then share your story. Let the world know of what it took – the oceans crossed and the years lived – to get you to this moment today. May I always remember my dad’s story and his legacy for many of us who share music with our communities today.

Rita with members of PICAA at the Immigration Museum, on the opening night of the exhibition Tatau: Marks of Polynesia, Melbourne, 2018. Photo: PICAA Inc.

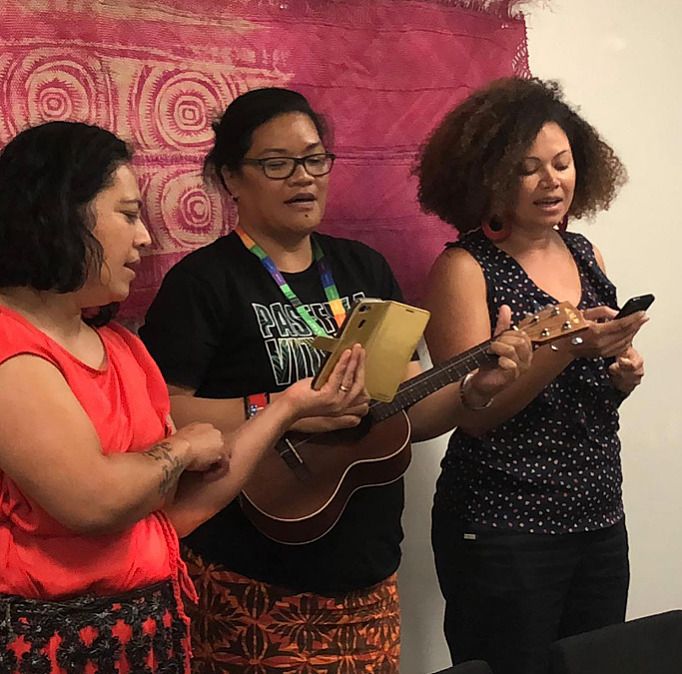

Rita, as researcher at the Melbourne Museum, leading her colleagues Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, Lisa Hilli et al. in song, Melbourne, 2020. Photo: P Preuss

Northgate CCCS on their 30th birthday, featuring their leader Reverend Elder Aviti Etuale and his faletua Sa, 2019, Melbourne. Photo: A Milo

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy.

Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photo: Seumanutafa with his daughter Rita, and grandchildren Jeramyah, Malia and Osty, Melbourne, 2018. Photo: Kaiga Media