We are Recirculated Assemblages: Louise Menzies at Hocken Collections

It matters who we think with, and which stories we choose to tell

It matters who we think with, and which stories we choose to tell.

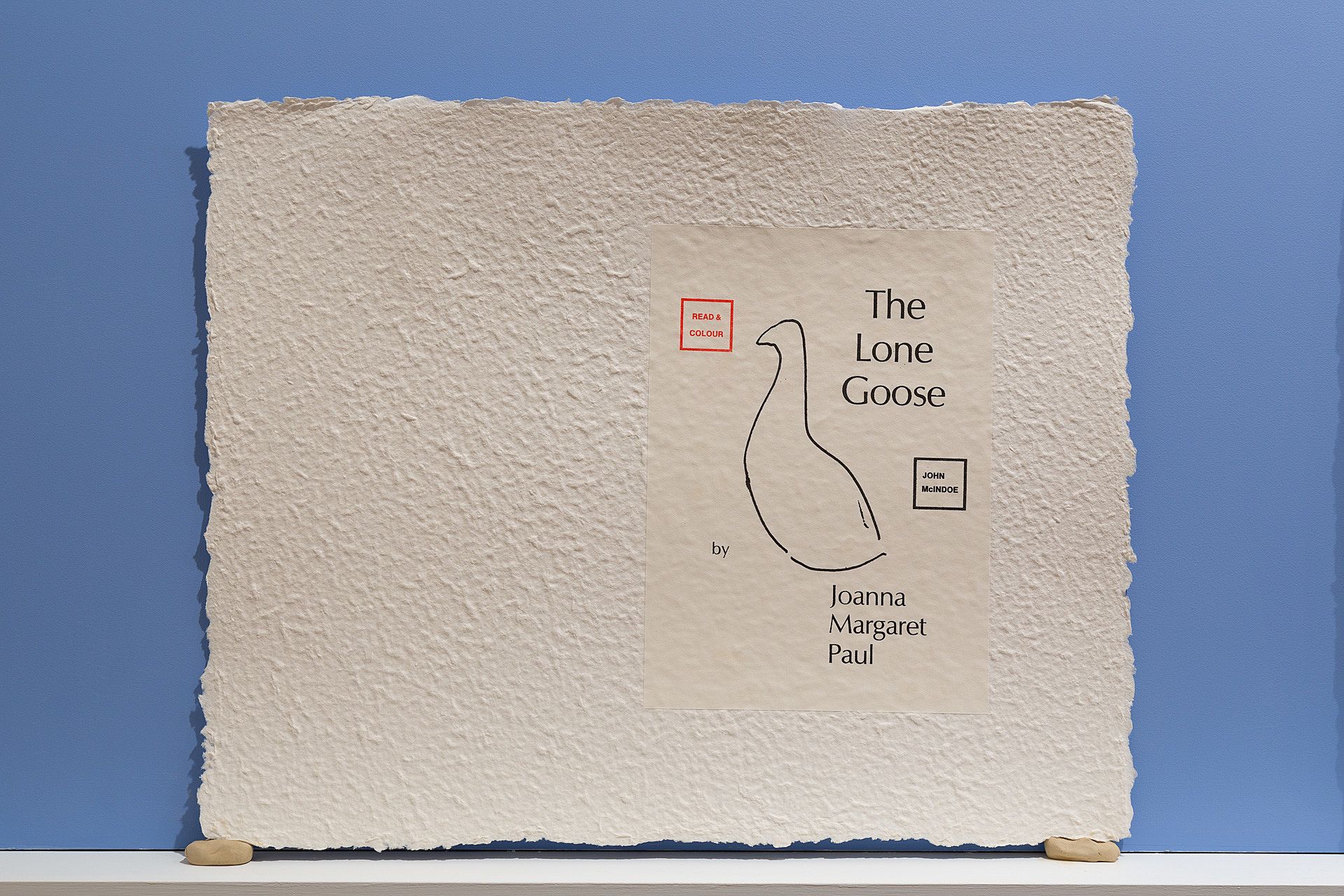

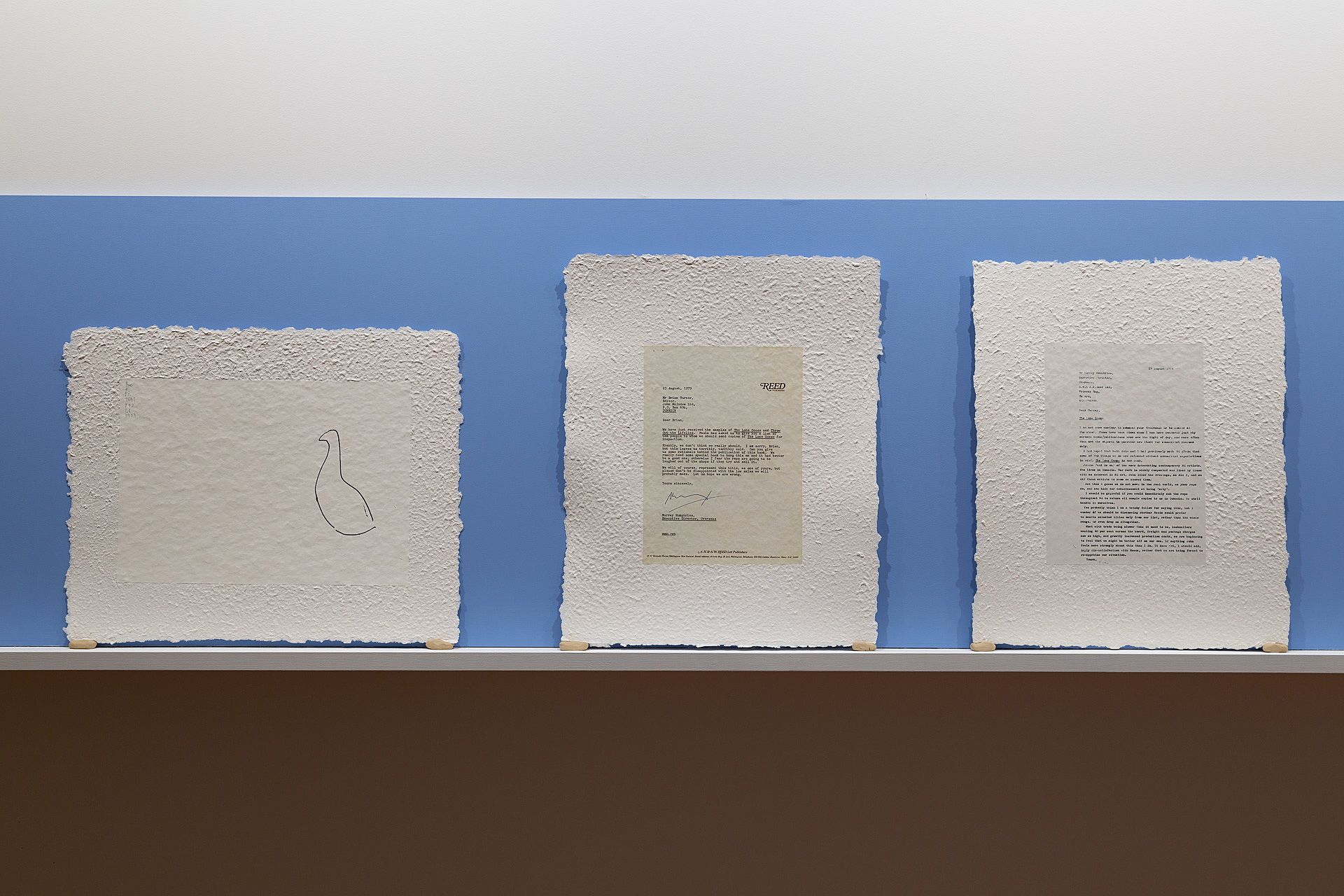

I want to begin with the little clay feet that brace large sheets of handmade paper. Not only because every story needs an origin, but because the act of providing support and raising up – this time for marginalised artists and communities – exists at the heart of Louise Menzies’ cross-media practice. In her exhibition In an orange my mother was eating at Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena, Menzies, the 2018 Frances Hodgkins Fellow, brings to our attention the work of three female artists: Frances Hodgkins (1869-1947), MC Richards (1916-1999), and Joanna Margaret Paul (1945-2003). Of these three artists, Hodgkins is perhaps the best known to an Aotearoa audience. However, it is not Hodgkins the famous expatriate artist that Menzies celebrates, but Hodgkins member of the precariat, designing textiles during a time of particular financial difficulty in the mid-1920s. In a similar manner, Menzies retrieves from the archive and presents a difficult moment in the life of painter and poet Joanna Margaret Paul – a moment from the late 1970s, when her children’s book The Lone Goose (1979) failed to garner support from her publisher’s distributor.

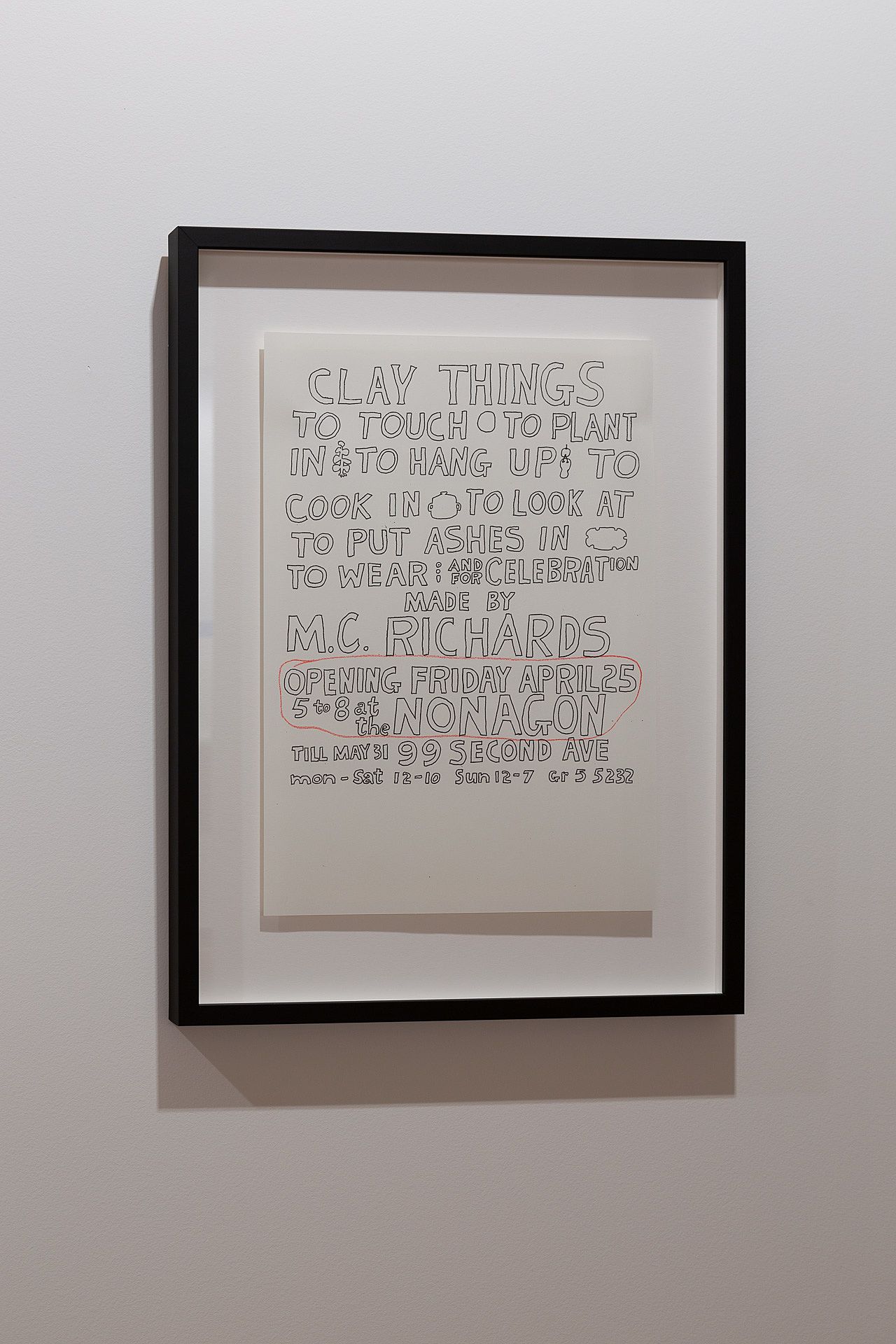

Menzies’ retrievals and reinterpretations of Hodgkins’ textile design and Paul’s children’s book can be seen as both a (necessarily delimited) form of collaboration, and an attempt to compassionately and inventively recirculate the marginalised aspects of these two artists’ lesser known works. The third artist that Menzies invokes, MC Richards, stands a little outside this grouping. The artefact of Richards’ that Menzies has chosen to reinterpret is not an artwork, but a poster advertising Richards’ 1958 exhibition. That said, Richards’ original handwritten poster could also easily be considered an artwork. Advertising her exhibition Clay Things to Touch, to Plant in, to Hang up, to Cook in, to Look at, to Put Ashes in, to Wear, and for Celebration, it is here that we find the impetus for the little clay feet bracing sheets of handmade paper. From the many possible applications of clay on Richards’ poster, Menzies has materialised the feet as supports for excerpts from Paul’s children’s book The Lone Goose, and correspondence between Paul, her publisher, the distributor, and associated parties, which are embedded into large sheets of handmade paper. These two newly iterated works, poster and children’s book, speak to each other from opposite sides of the large main gallery space.

...Menzies raises up what these artists had to do in order to continue making work, the difficulties they faced, and the marginalisation they experienced either during their lifetimes, or since their death, or both

In an orange my mother was eating is rich with discursive relationships within and between artworks, such that a type of familial resemblance exists despite the disparate eras, styles, and practices of the three artists Menzies works alongside, and despite the different forms Menzies’ works take: digital video, prints set in handmade paper, framed Risograph print, textile, printed matter. The discursivity of Menzies’ interactions as they materialise into traditionally marginalised media such as textile and handmade paper (to name two prominent examples) perform distinctly feminist actions of retrieval, reinterpretation, recontextualisation and recirculation. Or to nuance that claim somewhat, it is the aspects of the three women’s practices that Menzies works with that individually and cumulatively offer an occasion to remember and re-evaluate what it is to be a female artist in a normatively heteropatriarchal (art) world. As with earlier projects on forgotten histories, Menzies raises up what these artists had to do in order to continue making work, the difficulties they faced, and the marginalisation they experienced either during their lifetimes, or since their death, or both. In conversation with Hodgkins, Paul and Richards, Menzies’ exhibition is concerned with the intersection of artistic practice and financial imperatives, or career: both historiographies of careers, and contemporary pressures on artistic careers.

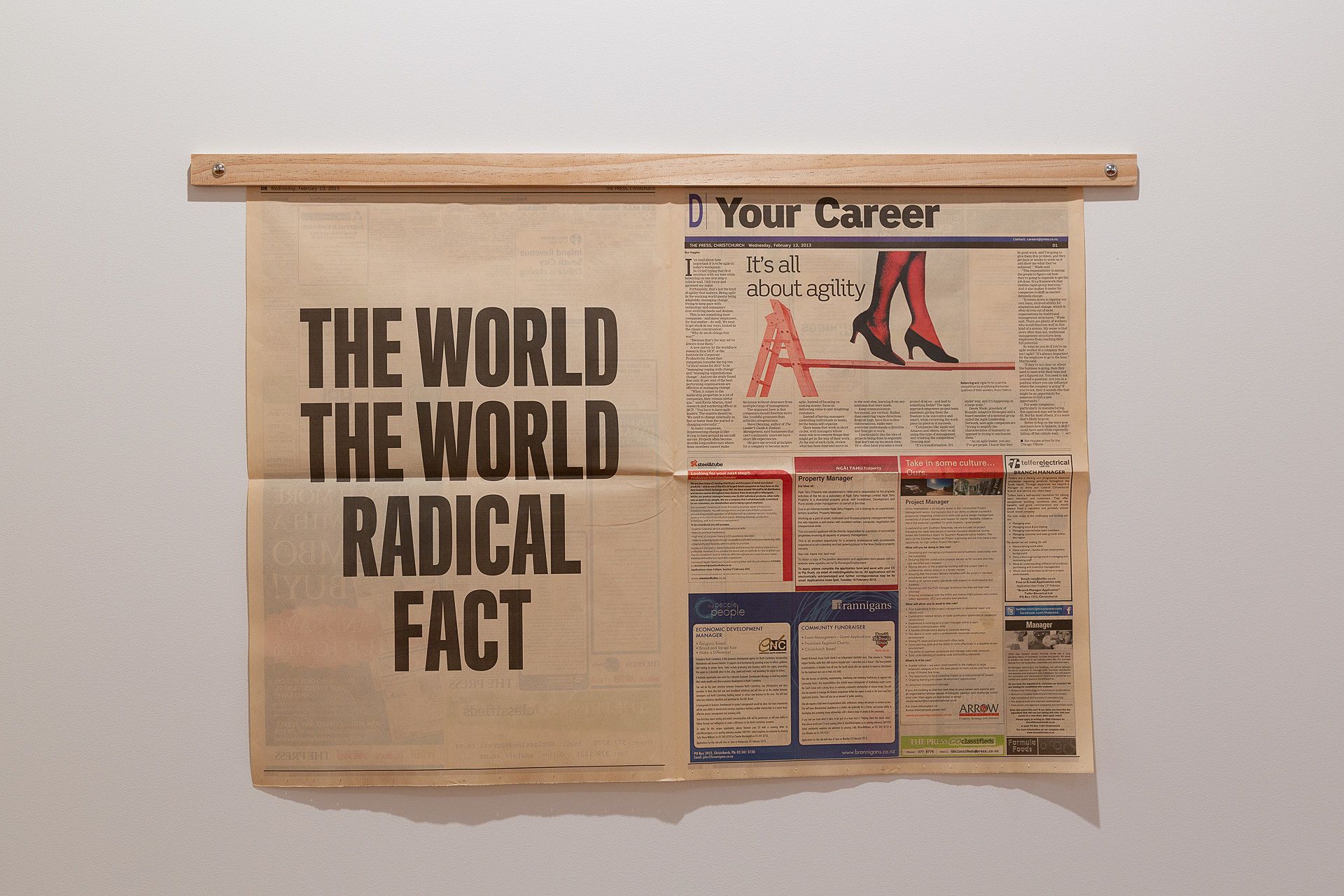

Three separate but interrelated works in the smaller right-hand gallery speak to difficulties of art making through the mechanism that yokes historiographies and contemporary practice: time. In many ways, the unassuming lynchpin of Menzies’ exhibition is the self-referential work The World, The World, Radical, Fact (2013/2019), a page work printed in an issue of Christchurch’s The Press on Wednesday, February 13, 2013. Occupying a whole page of the newspaper, the work comprises the titular phrases centred horizontally and vertically. They are, in part, translations of newspaper names such as Le Monde (The World). This subtle intervention gains traction and further connotative meaning when the newspaper is opened out to reveal “The World, The World, Radical, Fact” vertically stacked on the left-hand side, opposite a job vacancies page on the right-hand side with the header: ‘Your Career,’ by Rex Huppke. The by-line beneath ‘Your Career’ reads, “It’s all about agility,” and the piece itself is peppered with catch phrases like “being adaptable, managing change, trying to keep pace with consumers’ ever-changing needs and desires.”

With this repeated application of Hodgkins’ textile design to three never-more-quotidian chairs, Menzies amplifies the everyday, stopgap nature of Hodgkins’ financial situation and temporary employment at this time

The World, The World, Radical, Fact is affixed to the wall above a temporary sculpture comprising three chairs from the Frances Hodgkins studio that Menzies has had reupholstered. Temporary, as they will eventually be returned to the studio, each piece of furniture – adjustable office chair, padded three-legged stool, and rigid office chair – has been reupholstered with a contemporary version of an original textile design by Hodgkins: Untitled (textile design no. ll), 1925. The design, which Hodgkins would have originally made for Forrest Hewit of the Calico Printers’ Association, centres on the iterability of a black hybrid shape that is part rectilinear, part circular, and set against a brilliant pink-red background. With this repeated application of Hodgkins’ textile design to three never-more-quotidian chairs, Menzies amplifies the everyday, stopgap nature of Hodgkins’ financial situation and temporary employment at this time. There is also, to trade on the theme of recirculation, something decidedly ‘full circle’ in Menzies’ application of Hodgkins’ design to furniture belonging to the fellowship eventually established in her name.

The discursive relationship between the newspaper work, with its call for agility, adaptability and change management, and Menzies’ recirculation of Hodgkins’ financially precarious moment is extended by the third work in this grouping: a twelve-month, February to February calendar titled 2019 (2018). A calendar marks time, and Menzies’ calendar simultaneously plays with time whilst also acknowledging its importance: the latter with particular reference to her own year as the Hodgkins fellow. Known equally for her text-based works and artist books, she has based the calendar, which was designed with Dunedin-based artist Matthew Galloway, on the principle of repeating months. The first month of the calendar, February 2019, is an altered reproduction of a February 1991 calendar month, and March 2019 is an altered reproduction of December 1989, with the corresponding days and dates matching. The wide variety of calendars sampled in this project is the result of Menzies’ long hours spent in the extensive ephemera collections at the Hocken, and includes calendars from the Māori Women’s Welfare League, Country Calendar, and Everyday Goddesses – celebrating women from Nelson. The design element that links such varied calendars is a physical collage that connects between pages through the use of different die-cuts (shapes punched out to reveal a portion of the following page). For the range of die-cuts Menzies drew on another historical archive, this time at Dunedin Printers, who still retain a collection of one-time or occasional die-cut moulds. Menzies’ reprising of calendar months echoes the re-presentation of the newspaper work, with its two respective dates of 2012 and 2019, by underscoring the self-referential significance the newspaper work must hold for Menzies to exhibit it in a new context. In such a way, this re-presentation embodies Menzies’ idea that you have to trust in the presence of an object that appears to be travelling with you.

If Menzies’ newspaper work is travelling with her, so too is the life and work of US artist MC Richards. In her artist talk in mid-February, Menzies expressed the importance of Richards, even if she is only directly invoked in one poster work. Richards was a powerhouse and the exhibition poster points to the significance of her practice. But, as has historically been the case for women artists, Richards has slipped into obscurity, while her Black Mountain College colleagues John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg continue to burn brightly. Menzies and US art historian Jenni Sorkin are separately engaged in the project of bringing Richards back into wider consciousness. Both draw on the archival remnant of Richards’ poster advertising her exhibition Clay things… (1958). According to Sorkin, Richards’ exhibition qualifies not only as a Happening, but as the first Happening – a full year before Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 parts in 1959.[1] On the basis of Richards’ Clay things… Sorkin attempts to move Richards “to the center, rather than the periphery of experimental practice.”[2] Perhaps in a different world it would not matter who got there first, but Western culture and art history place immense importance on chronological precedence. In this particular climate where precedence equals prestige, being first generates a place in the canon, retrospective exhibitions, cultural capital and sales. Or rather, it does if you are a (white) male artist.

Menzies’ engagement with Paul’s work can be seen, in part, as an engagement with motherhood, and an extension of her thematic concerns with art making, financial precarity and patriarchal gatekeeping

Menzies may not necessarily share Sorkin’s efforts to reinstate Richards at the centre of mid-20th-century experimental practice, but her re-presentation of Richards through her poster is at the very least an opportunity to explore Richards’ life and work. As a self-described “teacher, potter, poet" who lived in a series of intentional communities, and worked at the crossing point of inner and outer realities, Richards’ philosophies, ceramics, paintings and poetry have much to offer.[3] In the context of Menzies’ exhibition, with its focus on the vicissitudes of career and historiography, and in relation to the West’s emphasis on hierarchies of precedence, Richards gives us pause to consider how different processes of evaluation and canonical construction could engender inclusive and non-hierarchical realities.

To a lesser extent than Richards, the work of New Zealand artist and poet Joanna Margaret Paul was undervalued during her lifetime; from the 1970s, when Paul first began to make experimental films and poetry in the early days of feminism (or women’s lib), more or less until her death in the early 2000s. The main aspect of Paul’s practice that Menzies accents is the way Paul blended art and life, refusing, as Jill Trevelyan writes, “to see them as mutually exclusive.”[4] Menzies’ appreciation of the flow between domestic and artistic life is evident in her re-presentation of Paul’s undervalued children’s book The Lone Goose, and in her use of the poem Where was I born? (1981) in her digital video work, and of a line from that same poem as the title for the exhibition. Of the three artists Menzies works with and alongside in this exhibition, Paul was the only one to have had children. Menzies’ engagement with Paul’s work can be seen, in part, as an engagement with motherhood, and an extension of her thematic concerns with art making, financial precarity and patriarchal gatekeeping.

Menzies’ recirculation of Paul’s The Lone Goose comprises selected pages from the children’s book and correspondence between publisher Brian Turner of John McIndoe, distributor Murray Humphries of Reed Publishing and Paul, and a letter of support from Norah Familton of the Dunedin City Public Library. Facsimiles of this correspondence are interspersed with remade pages from The Lone Goose, and all pages are embedded in the fibrous paper, which is handmade by Menzies. Where Paul’s publisher, Turner, describes the book as “pure organic pleasure!” Turner’s distributor Humphries responds cuttingly, “I am sorry, Brian, but this leaves us terribly, terribly cold.” The drama ensues as Turner tries to gain support for the beleaguered children’s book, and presses Paul into ways of “marketing” it. The Lone Goose is a beautiful book that reveals Paul’s skilful use of line to capture form. Menzies’ interpolation of correspondence with recreated pages from the book itself brings to light the difficulties attending a genre considered to be marginal, made by an artist who, as artist Peter Ireland writes,“existed on the margins of the art world: where she lived, how she practised, and what she believed in.”

Menzies chooses to concentrate precisely on the interweaving of familial and artistic lives, on what it means to live and make art with young children

In a recent article on Paul’s experimental films, arts writer Eleanor Woodhouse describes Paul’s work as “ungraspable and oblique, a many-faceted and shifting thing that denies easy comprehension, and has always resisted classification and assimilation into any existing framework or canon of New Zealand art.” It is a description that reflects a late-20th-century resistance in Aotearoa to interdisciplinary practices such as Paul’s, and to her unashamed focus on the objects and events of everyday family life. Menzies chooses to concentrate precisely on the interweaving of familial and artistic lives, on what it means to live and make art with young children. She explores this thematic in her digital video work In an orange my mother was eating (2018).

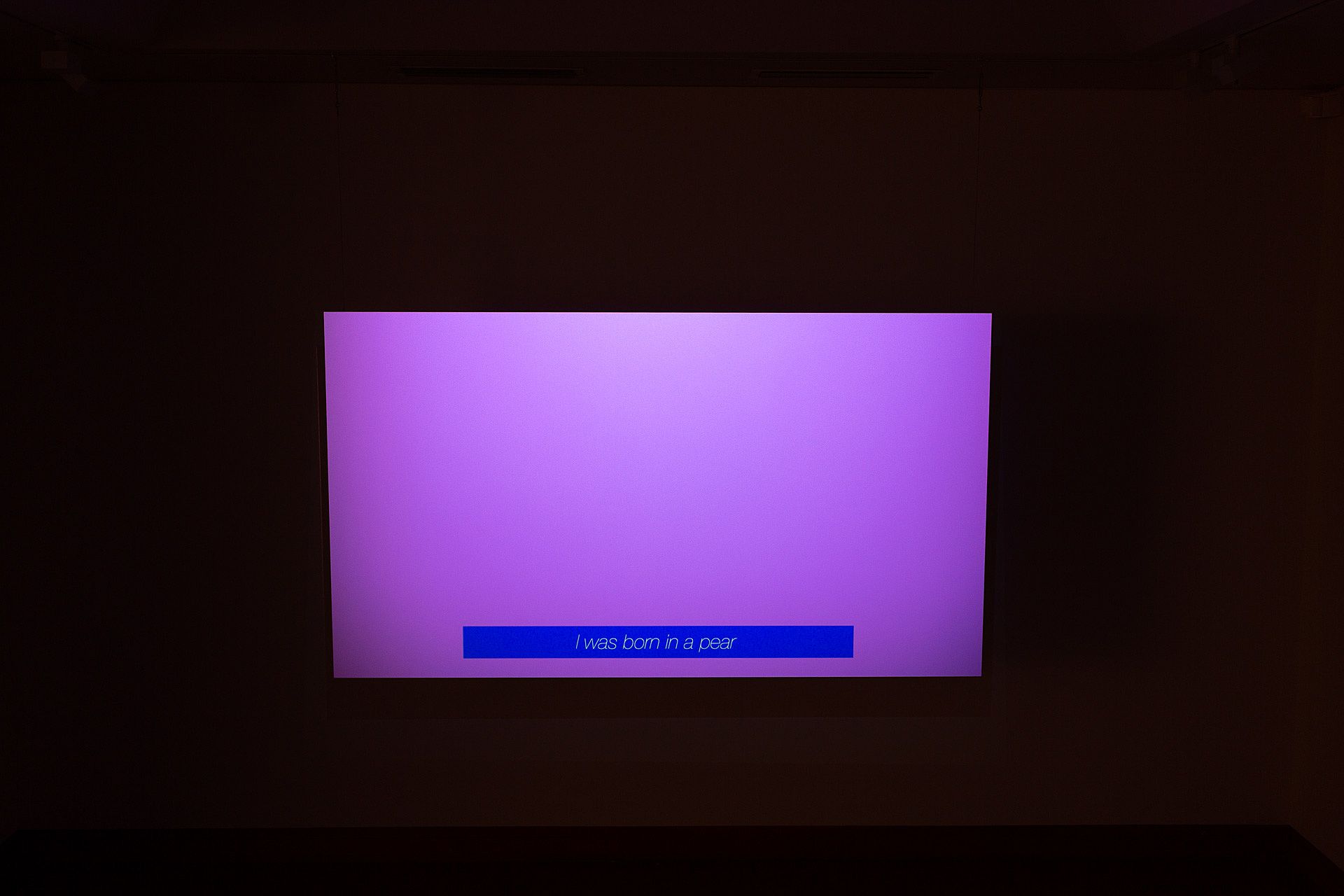

In this film, Menzies intersperses two short narrations of trips taken with her daughter Ezra, to Pigeon Hill and to Moeraki, with Paul’s poem, and a cameo of Paul’s son, Pascal Harris. The film alternates between digital colour fields with Paul’s poem delivered line by line as white text on an electric blue band, stills of Pascal, and of matagouri at Moeraki. Paul’s poem Where was I born? (1981), which records a conversation between Paul’s daughter Maggie and her friend Charles, both aged five years, is the film’s dominant thread. The poem is an extraordinary record of imagination, as the children list possible places where they might have been born (in an orange, a hot fire, my bones, a pea). It also evinces Paul’s attunement to and valorisation of her children’s world. Menzies’ short narratives formally mirror Paul’s poetics of the short line, as in the following excerpt, “this is Pascal / Joanna’s son / that’s her there / in the photo.” In this short excerpt, which is paired with a still portrait of Pascal, Menzies brings another child of Paul’s into the work. It is as if Menzies is honouring Pascal’s relationship to his mother. In a separate commentary on his mother’s work, Pascal writes, “I remember feeling, not thinking, / that I was part of her body.”[5] Yet another intergenerational relationship can be found in the film’s soundtrack, The Empty Foxhole (1966) by jazz musician Ornette Coleman. Suggested by Menzies’ partner Jon Bywater, the track features father Ornette Coleman and his ten-year-old son Denardo Coleman on drums. The jazz soundtrack and loosely syncopated subtitle format remind me of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ text-based animations in Adobe Flash, but you can breathe more easily with Menzies’ work.

But do we acknowledge our assembled nature?

Menzies’ exhibition makes me think about many issues, but mainly about relationships, and especially the politics of relationships. We are always in relation to others. We live our lives as assemblages of assemblages, to paraphrase writer, artist and philosopher Manuel DeLanda.[6] But do we acknowledge our assembled nature? And if we do, who do we choose to acknowledge? For every canonical reference, another artist or writer is quietly diminished and slowly erased. Donna Haraway summarises the essentially political act involved in going beyond the canon with her well-known dictum: it matters who we think with, and which stories we choose to tell.[7] In this exhibition, and in previous bodies of work, Menzies makes productive allegiances with the less-loved, under-appreciated, and overlooked moments in artist’s lives in an effort to help us think about what it means to make art, who gets to decide it is art, and how we can make the process more equitable.

Louise Menzies: In an orange my mother was eating

16 February – 30 March, 2019

Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena

[1] Jenni Sorkin, “The Pottery Happening: M. C. Richards's "Clay Things to Touch...” (1958),” Getty Research Journal 5, (2013): 197.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, 200.

[4] Jill Trevelyan (and Sarah Treadwell), Joanna Margaret Paul Drawing (Auckland: AUP Press and Mahara Gallery, 2006), 11.

[5] Pascal Harris, Light on Things: Joanna Margaret Paul (Dunedin: Brett McDowell, 2016), unpaginated.

[6] Manuel DeLanda, Assemblage Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 3.

[7] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 12.