Lost In The Darkness

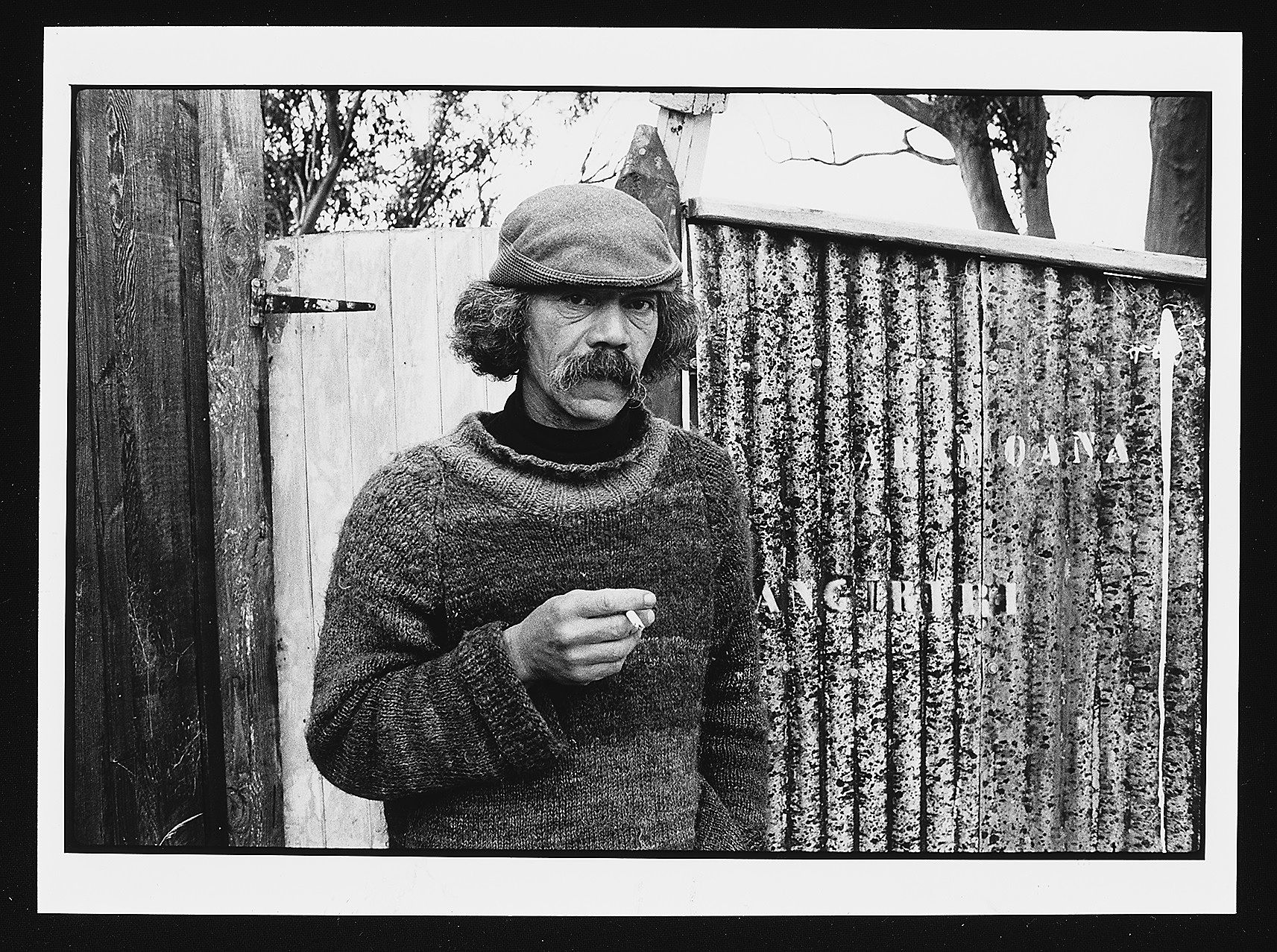

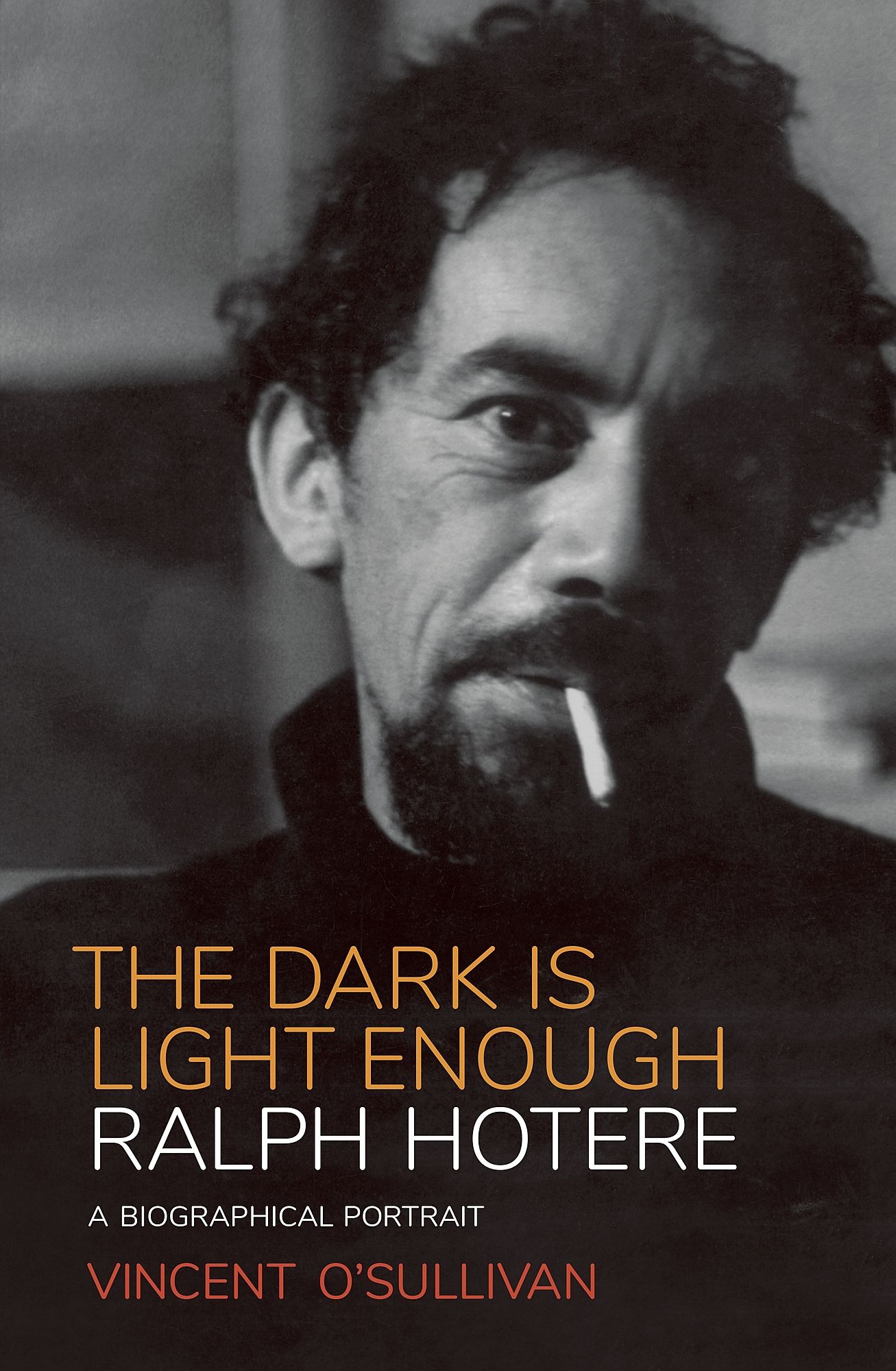

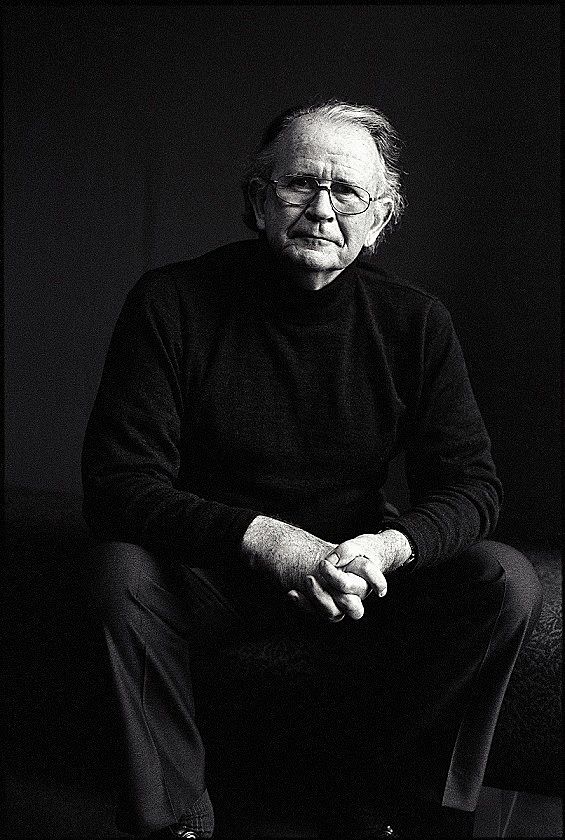

An extract from Vincent O'Sullivan's biographical portrait of Ralph Hotere, The Dark Is Light Enough.

Ralph sent his mother a postcard in August 1962, with news she was waiting to hear. ‘We are in Italy,’ he told her, ‘on the way to the Sangro River. We go on tomorrow to Rome ... At the moment we are staying in a motor camp in a town called Alassio on the sea with John Lee and his wife also who have come down from England. Yesterday was my 31st birthday. Had a nice day.’ He signed off, ‘Raukura and Bet.’ Those were important places to the family, Rome and Sangro.

Here were the great monuments of the Catholicism he was raised in, the filaments that ran from the small wooden church in Mitimiti to St Peter’s Basilica, where he made a sketch of Michelangelo’s Pietà. There was an even stronger incentive to cross the country to the military cemetery south of Ortona on the Adriatic coast, near the Sangro river. It meant a great deal to Ralph, as it did for his whānau back home, that he was the first to visit his brother’s grave. Among his strongest memories was Jack in uniform, on his final leave, playing his guitar at the party at their home in Taikarawa while Ralph leaned on his brother’s knee. Now he stood near Jack again, at the simple sandstone grave with its name and regimental number beneath the stylised New Zealand fern, and the date 23.12.43. Rows of graves fanned out to either side of it, with the names and ages of others who died on the same campaign.

The million small deeds by which a military formation moves are like the separate strokes of a painter’s brush

Jack Hotere’s story had its parallels with hundreds of other young Māori who left their small communities and farms to find their graves in places they had never heard of. Ralph knew some of the details of his brother’s story, but not all. Jack had enlisted in the Territorial Corps at Rawene, a few hours from home, then done basic training for six months at Ōkaihau, another six in Auckland at Narrow Neck, further weeks at Trentham, and finally at Papakura. He sailed down the Waitematā in July 1943, and a month later was with the Māori Battalion in Egypt. But for ‘the 28th’, fighting in the Middle East was at an end; the front had moved across the Mediterranean to Italy.

With most of the New Zealand Division, they were to begin on what was considered ‘for the Allies one of the most toilsome campaigns of the war’. The Battalion had arrived in the heat of Egypt to train for a markedly different climate and terrain. Part of the toughening up was the longest march the Division was ever to make, the hundred miles from base camp at Maadi to the ships at Alexandria that would take them to the southern end of the Italian peninsula. It would be another month before newspapers at home were permitted to announce where ‘the boys’ were now engaged.

The intention was to take Rome, with a three-part plan that would move Allied forces up both the western and the eastern sides of Italy, and a coastal landing in Anzio. Jack was with the New Zealanders and other Dominion forces who moved quickly along the eastern route, between the sea and the high central chain of mountains. They would confront the German lines at the Sangro river. What at first was expected to be a fairly straightforward advance turned into a tough ordeal. Quite apart from the experienced Panzer and parachute divisions set to impede them, Italian geography seemed to be working for the enemy. As did the weather. Within a few weeks, a mild autumn had moved into bitter winter. The broad shingle bed of the Sangro, with its braided channels and its backdrop of high snow-clad peaks, put South Islanders in mind of home. After heavy rain the levels rose quickly, the channels became torrents. And once the rain started, the poorly maintained roads and the scoured tracks were quagmires.

In the first few weeks there was little engagement with the Germans. When the two armies came to close quarters, the Māori troops were held back in a supporting role. The first New Zealanders crossed the Sangro at the end of November with, as the official war historian put it, ‘many men fighting their first action. The country across the river became more hazardous. The plan to move swiftly on Orsogna, the little town almost directly level with Rome on the country’s other side, became a matter of one ridge slowly taken, then another.’ Early in December the Māori Battalion moved along a spur towards an escarpment rising sheer above the Ortona road.

In the middle weeks of December there was intense fighting in the rough, broken hills under cold, overcast skies. Planes bombed the Allied positions, while the ground attacks persisted. In one of the bizarre pieties of war, ‘By a kind of tacit agreement the cemetery was left vacant by both sides.’ It was on ‘one of these raids made on most days’ that Jack Hotere, aged twenty-two, was killed on Thursday, 23 December. Back home, the family had celebrated Christmas before Ralph, on horseback on the hill behind the farm, saw the official telegram delivered that informed the family ‘with regret’. Jack’s letters home continued to arrive into the new year. A chaplain wrote to the family, saying how Jack had died attempting to help his best mate, and was buried beside him.

‘Basically,’ ... ‘they are about the stupidity of war.’ The occasional celebratory ring of intense colour is an echo of what has been lost in the darkness

There is a distant irony as the war historian N.C. Phillips, searching for an image to suggest the difficulty of writing an account of confused warfare, hits on the image of painting. ‘The million small deeds by which a military formation moves and has its being are like the separate strokes of a painter’s brush, which compose themselves into intelligible purpose and design only when observed from a distance as parts of a total picture.’ There is a further irony that the Hotere paintings that came from visiting Jack’s grave so trenchantly challenge any such ‘intelligible purpose’ for those who died.

It meant a great deal to Ralph, and to his parents and family back home, that one of them at last had stood with Jack, drawing him back into the circle of the whānau. As soon as he and Bet were back in Vence, the emotional force of visiting the cemetery near Ortono, the stirred memories of his brother and the more general grief for young New Zealanders who had died in the same campaign, were directed to his first enduringly important series. It set a pattern for most of Hotere’s painting life. A deeply personal event, a compelling idea, a dominating public or political occasion, a resonant arrangement of words, would propel him to work on a series of paintings that expanded and diversified until their impelling drive was resolved.

Over the next eighteen months many of the Sangro paintings would take shape on the dismantled sides of small packing cases that had once contained television parts, with their central plywood panel surrounded by four raised strips of wood. The paintings mostly used the form of this thick dark framework, with the painting’s centre in vigorous bright colours, often insistent reds carrying the vividness of youth into notions of blood and confusion and loss. Their effect is insistently elegiac. ‘Basically,’ as Ralph said, ‘they are about the stupidity of war.’ The occasional celebratory ring of intense colour is an echo of what has been lost in the darkness that surrounds it. At times the running of paint and blood are deliberately paralleled. The repetitive ages of the young soldiers had struck home as Ralph walked the rows of graves. The numbers were now repeated in his paintings, at times like the simple scrawled figures on a school blackboard, at others blocked in with the kind of stencilling familiar to young men who had worked on farms or in freezing works or wool stores.

Te pō oti atu, the darkness we are all destined for

Now the men themselves, like the beasts and carcasses that had been their trade, were themselves ‘numbered’ as much as named. We were a country that exported youth. These numbers, across the broad bands of darkness that heavily sealed off the squares of living colour, conveyed too how individual loss merged into communal, repetitive, senseless death. In one work that was kept in the family, unusual in that it was painted on board with grey as its dominant colour, the right-hand section asserts in unusually large numerals the day, month and year of Jack’s death. To its left, an unpainted section of the board shows the grain and knotting of the wood, roughly in the shape of a heart; beneath it, a photograph of Ralph, kneeling, one arm resting along the top of his brother’s grave, holding against the tombstone the rosary his mother had given him to take from home.

For the first time Hotere used extensive areas of black, mostly in the wide framing borders. It was also, perhaps, the first occasion that he drew on the significance of black with the specific Māori resonances of what was meant by te pō. It carried a mythic force that went beyond the surface suggestions of night and darkness and the realm of death. In its fine gradations in Māori traditional thought, black might variously, and in this case so appropriately, present and represent te pō uriuri, the extreme darkness; te pō tangotango, the darkness that cannot be penetrated; te pō oti atu, the darkness we are all destined for. Ralph did not need to have one particular significance in mind.

As a Māori, and irrespective of the precise immediate ring te pō might have for him, he was using black with a range of emotional possibilities that were more extensive than a Pākehā viewer might have thought likely. This series that the visit to Jack initiated was the beginning of what, in terms of style and emotional depth, sets Hotere apart from other New Zealand painters — his now lifetime engagement with what te pō both declares and contains, what it takes to itself, what it allows to be revealed.

Not that Ralph explained in any way what he was doing. For another five decades, his remarks on what his art might ‘mean’ would be few, evasive, often a touch impatient. Already he was frank in his scepticism about professional critical writing. The phrase ‘elected silence’ is as apt as any for what Ralph considered the artist’s appropriate response to questions about his work. The answers, so far as he was concerned, were already given in the images that provoked them.

.

The Dark is Light Enough: Ralph Hotere – A Biographical Portrait, by Vincent O’Sullivan, is published by Penguin.