Loose Canons: Shane Bosher

Former Artistic Director of Silo Theatre and general theatrical maestro Shane Bosher pops by to tell us about the people and work that have inspired his career.

Loose Canons is a series in which we invite artists we love to share five things that have informed their work. Meet the rest of our Loose Canons here.

Shane has been a director, dramaturg, producer and strategic development consultant for the last 20 years. Following training at Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School, he has worked for all of New Zealand’s major theatre companies including Auckland Theatre Company, Downstage, Court Theatre, Circa Theatre, Bats, Fortune Theatre and the New Zealand Actors Company, as well as the Auckland Arts Festival and the New Zealand Festival.

From 2001 to 2014, Shane was the Artistic Director of Silo Theatre. During his tenure, he directed some of the company’s most lauded productions, including Angels in America, Speaking in Tongues, Private Lives, The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs, Tribes, Top Girls and Tartuffe. From 2015 to 2017 he was based in Australia, directing The Kitchen Sink for Ensemble Theatre, The Pride for Darlinghurst Theatre, Straight for Kings Cross Theatre and sell-out productions of Cock and The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant for Redline. His other recent work includes productions of Venus in Fur for Auckland Theatre Company, Jumpy for Fortune Theatre, A Streetcar Named Desire for Silo Theatre, Cock for Auckland Live and the world premiere of The Things Between Us for Christchurch Arts Festival. As a playwright, Auckland Arts Festival and Creative New Zealand supported the development of his latest work, Everything After, which won the Adam New Zealand Play Award for 2018.

He was named one of the Aucklanders of 2005 by Metro magazine and in July 2007 they named him one of the Most Influential People Under 40. He is the recipient of three Auckland Theatre Awards and has been awarded Director of the Year by the New Zealand Listener four times. He has undertaken professional development at the Donmar Warehouse and Young Vic in London, and The Public Theater in New York.

In 2018 he will direct the New Zealand premiere of Homos, or Everyone in America at Q Theatre for Auckland Pride and Cock for Circa Theatre.

FAMILY AND DRAMATURGY

There are artists and colleagues who come into your life when you most need them. John Verryt and Elizabeth Whiting have defined much of my working life. I grew up watching their work at Mercury Theatre and in contemporary dance. I often joke that it was John’s colossal evocation of a New Orleans village (complete with crumbling villa and shitting goat) for The Rose Tattoo that sent the Mercury under. I didn’t know until recently that it was Elizabeth who had clothed Kilda Northcott, Marianne Schultz, Shona McCullagh and others in vibrant saffron yellow for Douglas Wright’s Gloria. It was the first piece of contemporary dance I saw that really kicked me in the rubber parts and it makes absolute sense that she was involved.

Designers are a production’s dramaturgs. Sometimes the glory of their work is in the finest of details. John will strip things away until there seems to be nothing, but you’ve in fact been left with everything that is essential – these days he has zero interest in fussy adornment. He’s also wonderfully Dutch and no-nonsense, putting his finger on exactly what isn’t working dramatically in a production. I’ve bristled and wanted to hurl knives at him in rehearsal rooms when he’s rocked out the words “that bit’s boring” but he’s never been wrong.

Elizabeth is often the glue that holds a production together. She lives in texture and nuance, knowing that a lumpy cardie or the right pair of shoes can unlock a character’s performance. She’s an expert problem solver and will often work on the sidelines as a bit of a performance coach.

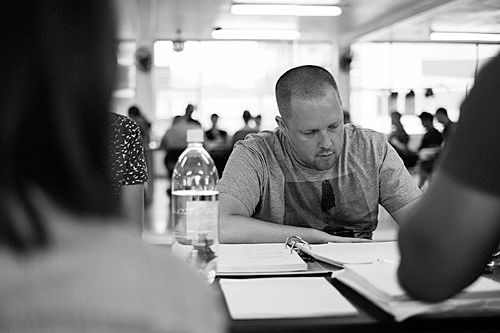

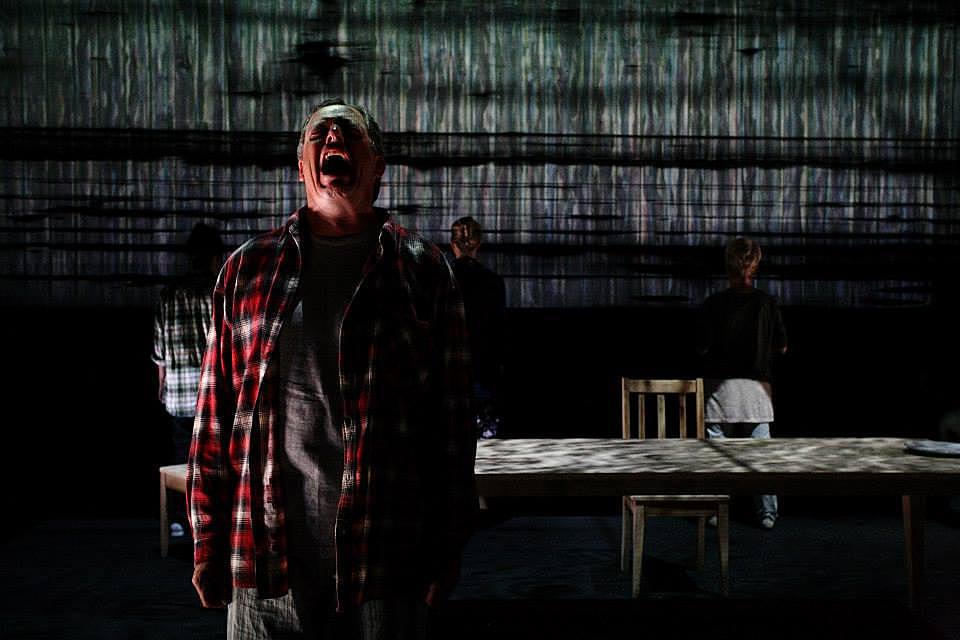

Years back we all worked on a production of When the Rain Stops Falling. It was one of those rare occasions when everything comes together: extraordinary cast, beautiful writing and composition, generous and well-imagined design. But it was a production that wasn’t necessarily easy to make. Peter Elliott and I were trying to wrap language around a moment of significant change in the play, where his character is removed from the story, leaving us with (just) a primal scream at the heavens. It’s the sort of moment in a play that can feel almost impossible to enter unless you know in every part of your bones what it is that you’re doing and why you’re doing it – and we were still very much feeling our way into it. In a costume fitting, Elizabeth blithely slipped the words “oh, he’s exorcising the trauma of the family tree” into conversation. And that was exactly it. Peter, being the fine actor that he is, was hovering around this idea already, but Elizabeth’s words gave him a kind of extra permission.

They’ve also rescued me more than once. When Silo Theatre was under threat, John invited me over for chicken soup to talk about everything but. Elizabeth has generously opened her home to me on more than one occasion. Not only are they great champions of my work, but they’re staunch critics of it as well.

They really are family to me. They are the backbone of our industry and it still completely befuddles me that they don’t have all of the letters and laurels after their names.

MURDER SHE WROTE

Because Angela Lansbury. Because memes. Because gloriously overcooked acting. Because cosy murder.

THE PICTURE OF DORIAN COREY

I’m known for getting lost in rabbit holes of research, Googling well into the night to find threads off threads off threads. I call them magnificent obsessions. Recently it’s been all about connecting with musical theatre geeks in Sweden about flop Broadway musicals.

Perhaps my greatest magnificent obsession, though, has been Dorian Corey. When I was at drama school, I encountered the doco Paris is Burning for the first time. It’s a love letter to the Harlem ball culture in the 80s. My friend Rhys and I would regularly hire it from Aro Video, drink cheap champagne and yell at the television.

Dorian is the queen in the peach nightie who unpacks what shade is. Throwing shade now seems to have been appropriated by almost everyone. We forget (or perhaps don’t even know) that it descends from slave culture and was claimed by African American women and gay men over time as a way of communicating covertly. Dorian gave us, the viewers, its context, its example and its meaning.

I fell down a rabbit hole with Dorian while trying to find out what had happened to all the doco’s subjects. Like many in the film, Dorian was one of the many to be claimed by AIDS. But here’s where it gets curiouser and curiouser. After Dorian died, a mummified body was found stuffed in a garment bag in the back of a closet. They reckon the body had been dead for about 15 years. Perhaps he was an abusive ex-boyfriend, perhaps Dorian killed him in self-defence during a burglary. Who knows? As I said, a magnificent obsession.

EMILY WRITES

My favourite poem is one I’ve never finished. Emily Dickinson, in full Gothic mode, wrote:

The soul has bandaged moments -

When too appalled to stir -

She feels some ghastly fright come up

And stop to look at her -

I mean, shut the front door. I’ve never read beyond that first stanza. There’s something just so immaculate about those first four lines, I just haven’t been able to risk reading what comes next, for fear it’ll turn into some wonky romantic hoo-hoo.

People think of depression as a passive state. Doom, gloom, alone in my room. I like to think that it’s a state of deep reflection that precedes change. The bandaged soul in this poem is a metaphor for the suffocating grip of depression, but it also suggests protection. I mean, if something is wounded, what do we do with it? To me, it’s a chrysalis moment – this soul is actually on the brink of transformation and change.

I use this image with actors all the time, to shepherd them away from sentiment and toward something more contradictory and trickier.

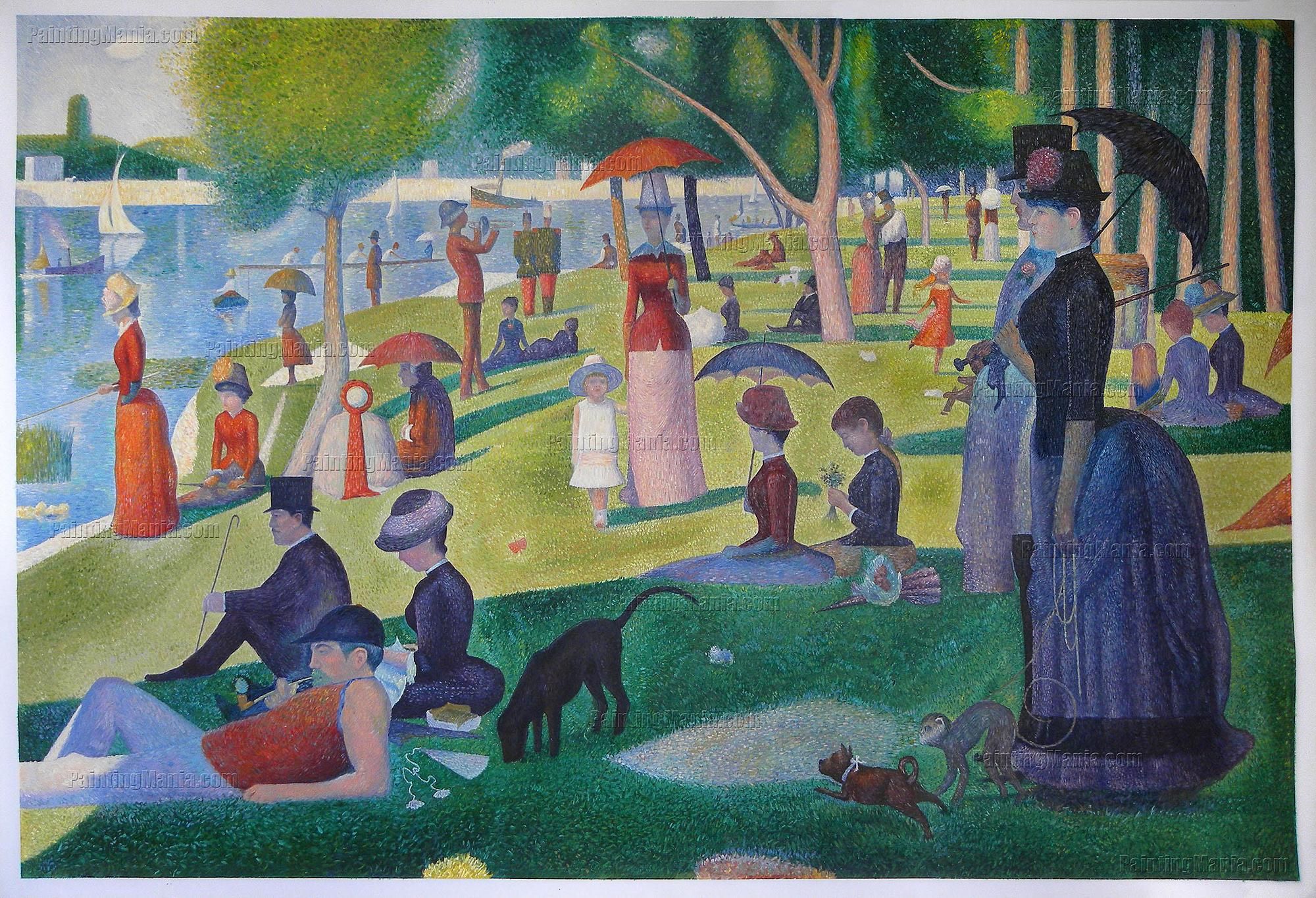

WHITE: A BLANK PAGE OR CANVAS

When I was a 14-year-old pretending like I wasn’t growing up in Hamilton, an older gentleman who seemed to have completely figured me out (before I’d even begun to) gifted me a TEAC cassette. On it was a ripped recording of Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George. It’s a musical inspired by the French pointillist painter Georges Seurat and his painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. But it’s really about our need to connect to our past and live in our present. It’s also about how fucking hard it is to make art.

I spent hours of my teenage years in my bedroom belting out Move On and have spent years of my adult life imagining the production I would make. Over time I’ve resigned myself to the fact that I will never be Bernadette Peters and that the show is perhaps just too niche to programme. To those of you who are reading, I would happily settle for Company, Night Music, Merrily or Into the Woods.

In 2011, I made a private pilgrimage to Chicago to visit the original painting. Standing alone in front of La Grande Jatte at 9am, I cried like a 14-year-old. Many of my friends have done the exact same thing. It really is a work (painting and musical) of majesty and spiritual grace.

Homos, or Everyone in America runs from January 30 to February 16 at Q Theatre as part of Auckland Pride Festival. Tickets available here.