Loose Canons: D.F. Mamea

Playwright and screenwriter D.F. Mamea shares the people and art that shaped him.

Loose Canons is a series in which we invite artists we love to share five things that have informed their work. Meet the rest of our Loose Canons here.

David Fa’auliuli Mamea (Safune, Safotu) has worked on theatre, radio, television and film projects, some of which have been produced and broadcast. He has won the Adam Award for Best New Zealand Play and the Playmarket Best Play by a Pasifika Playwright (Still Life With Chickens, 2017), the New Zealand Writers Guild SWANZ Award for Best Play (Goodbye My Feleni, 2013) and the New Zealand Radio Award for Best Dramatic Production (Skyblue, 2013). His next play, Kingswood, about four university friends and a classic Holden stationwagon, will premiere at BATS Theatre in September as part of the inaugural New Zealand Theatre Month.

D.F. identifies as a Wellingtonian even though he hasn’t lived there for almost two decades. He resides in rural Northland with his Lovely Wife, son, cat, dogs, ponies, kunekune pigs, and innumerable chickens, including a rooster called Ghost Dog.

Still Life With Chickens, about an elderly Samoan woman who befriends a Barnevelder, was inspired by his mother’s adventures with keeping chickens. The idea for the play, along with the title, was all his Lovely Wife’s. Still Life With Chickens had a sell-out season in the 2018 Auckland Arts Festival, has just finished a week on the Manawatū Plains at Centrepoint Theatre, and is coming to Circa Theatre in May.

I was a tubby kid. Sickly, too: I used to think a typical school year was a couple of months of class time, and then the rest of the year was staying at home, or being taken to one of my parents' jobs because they couldn’t afford babysitting. When I was twelve, they sent me to Samoa for my health and for high schooling.

Samoa in the early 1980s for a tubby kid from Hataitai: there’s no television – and worse, chocolate is too expensive to be a regular part of the diet. I walked everywhere because everyone walked everywhere. I began to read. With no screen to passively absorb pictures and radiation from, I would read for hours on end.

J. T. Edson, Mack Bolan, Robert Silverberg, Isaac Asimov. Then Ed McBain, Ian Fleming, Dick Francis, Philip K. Dick, Stephen King. After I returned to New Zealand, I discovered James Ellroy, John Le Carré, Alan Moore and Charles Burns. Then as I took up screenwriting it was James Cameron, William Goldman, Aaron Sorkin.

No female writers, but. I’m still working to address that.

Desperado

Put a screen in front of me and I would watch its flickering images like my life depended on it. All of that content over the first 30 years of my life – the Wonderful World of Disney and Sunday Horrors, George Michael’s Faith music video and Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker, ET the Extraterrestrial and John Carpenter’s The Thing, Unsub and the Dead Dog Records season of Wiseguy – it all came together after Robert Rodriguez’s Desperado.

My friend Stevo and I had loved Rodriguez’s debut, El Mariachi, and we had high expectations for his follow up. When we left the theatre we tried to process our disappointment. We spent an afternoon at the Southern Cross bar deconstructing the film then rebuilding it to our satisfaction. I realised at the end that it was all about story: why should I care about who and what happens to them?

This was where I first learnt two things I would take into my writing: one, give the audience what they want – but different; and two, grab the audience straight away, and don’t – let – go until the credits roll.

Bird

My brother, Sleep, gave me a Charlie Parker CD set one Christmas. When I put it on the stereo, it wasn’t some come-to-Jesus moment, it was like, what the heck is this (it’s bebop), why is he going so fast (because he’s awesome), and what the devil is he doing to these jazz standards (he’s owning them). Art Pepper, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan followed. Then Nina Simone, Etta James, Blossom Dearie, Claire Austin and Diana Krall.

Give any one of them a jazz standard and you’ll get something utterly familiar yet absolutely distinct to the performer. That’s how I want to write.

Ella

When I met the woman who would become my Lovely Wife, we agreed that if we were to get together, we would only have puppies, and lots of them. Our first was a ‘West Auckland special’ – an eight-week-old puppy who fit in the palm of my hand, described at the pound as a mastiff-Rottweiler cross. We named her Ella.

The pound description gave my wife nightmares about how we were going to be able to afford to feed her, while I visualised a million self-portraits of ‘A Man and His Hound’. Ella grew into a medium-sized Staffordshire-Alsatian cross with the heart of a lion and the appetite of a rampaging gojira so the food bill was manageable, and self-portraits were never a goer anyway.

She died last year. I can’t believe I still miss her. She was just a goddamned dog. But she was our dog.

Sleep

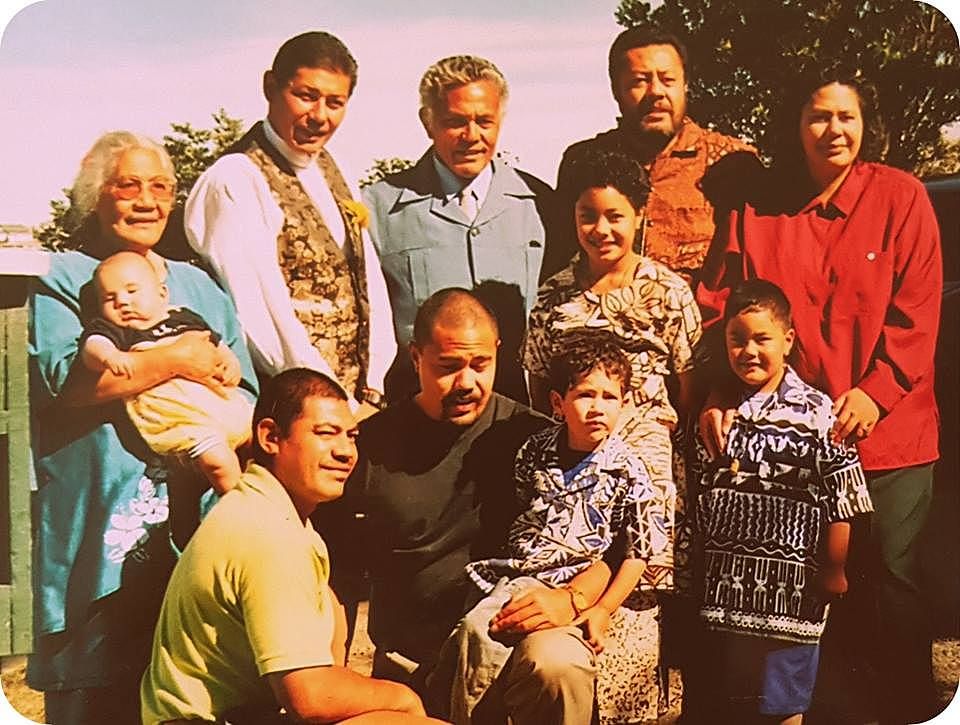

Silipa Mamea jun, 1959-2002. I can’t seem to get away from my brother. But I owe him my creative career: he introduced me to comics; he encouraged my drawings of soldiers and tanks and jet planes and flying saucers; and he took me to the opening night of Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall, which blew everyone’s minds at the time.

When I joined the workforce, I was constantly identified as ‘Sleep’s little brother’. I resented being in his shadow. I envied his independence. He had everything and I was nobody.

After he died, I found that I kept writing him into my stories. He’s a part of me and my life, and credit where it’s due, man – he gave me my first comic, and I haven’t looked back since.

Still Life With Chickens runs from 8 May – 2 June at Circa Theatre, and plays one night at the Taupō Winter Festival on 12 July. Tickets for the Circa Theatre season are available here. Tickets for Taupō Winter Festival are available here.