Loose Canons: Toby Morris

Toby Morris on Tintin, radicals, comics as journalism, and learning to be a different kind of man.

Loose Canons is a new series in which we invite artists we love to share five things that have informed their work. Today we hear from illustrator-gone-viral Toby Morris.

Since drawing his first comic as a child, Toby has gone on to forge a career as an illustrator and designer. He draws the monthly non-fiction comic The Pencilsword for The Wireless, and is half of the Toby & Toby combo behind the weekly series That is the Question for Radio NZ. He also draws concert posters for bands like Beastwars, Liam Finn and The Phoenix Foundation.

Toby will be one of the panelists at our upcoming event The Kill Screen, a conversation with artists on beginnings, ends, and killing your darlings.

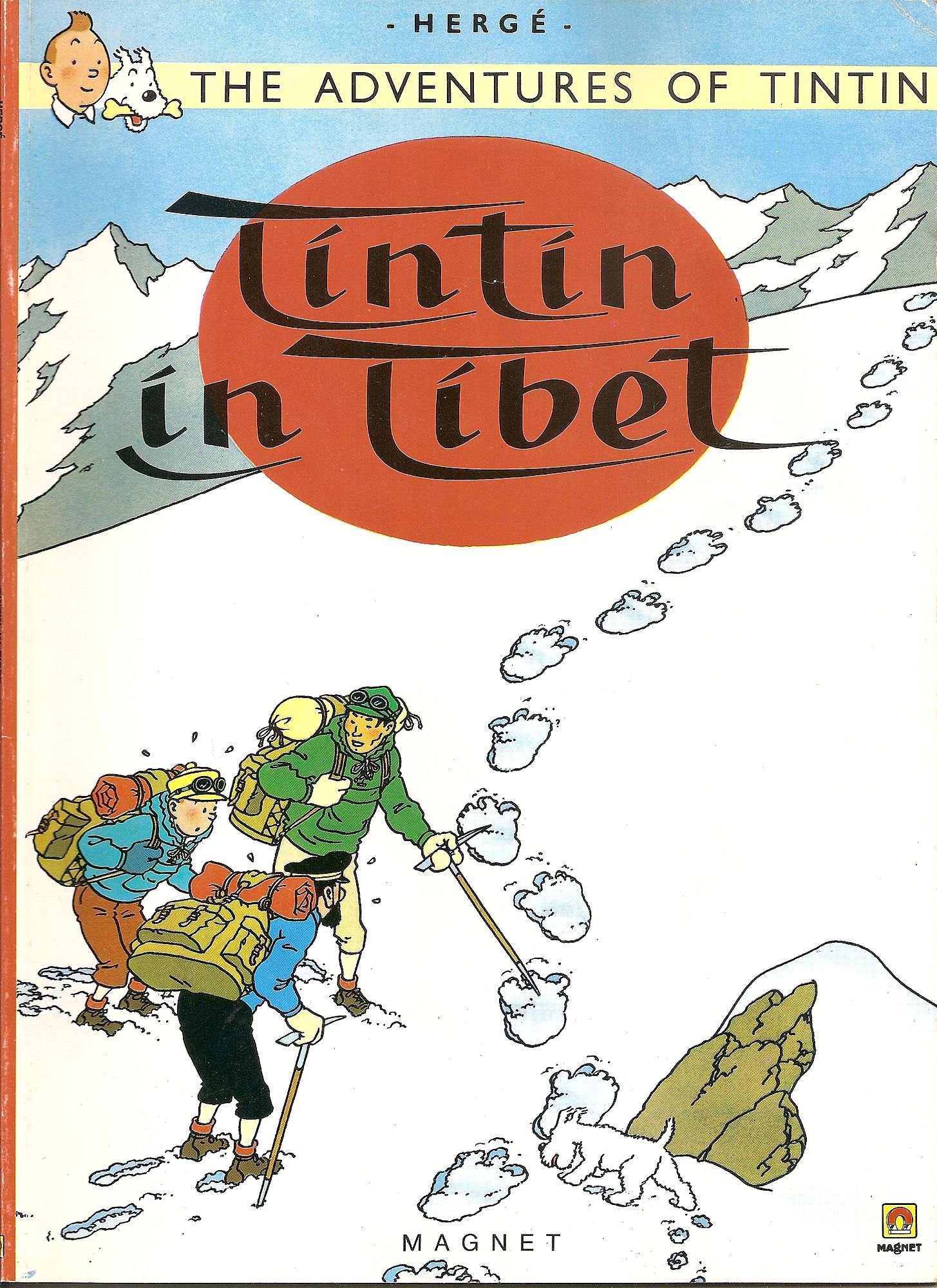

Tintin in Tibet

The first thing people often say when they see my drawing style is “Tintin?” Or sometimes “Tintin” somewhat accusingly. I’ll cop to that, without any shame. As a kid I received a gift of a big stack of Asterix and Tintin books and it really was a life changing event. And while Tintin is known for fast-paced adventures, it was always the calmness of Tintin in Tibet that fascinated me most. In this one there are no villains and very few twists and turns. It’s a clean and clear-minded story of a mission: An old friend of Tintin’s is in a plane that crashes in the Himalayas. Tintin goes to find him. That’s it.

But into a simple form Herge packs a whole world. As a kid I admired Tintin's pure dedication and bravery. I was fascinated by the glimpse into Buddhism, and loved being transported so convincingly to the top of the world. As an adult I read it again and see a writer grappling with themes of loyalty, mortality and his own creation that threatens to consume him. “Cut the rope,” says Captain Haddock, dangling helplessly from a climbing rope tied to the fearless boy reporter. “Better for one to die, rather than two isn’t it?”

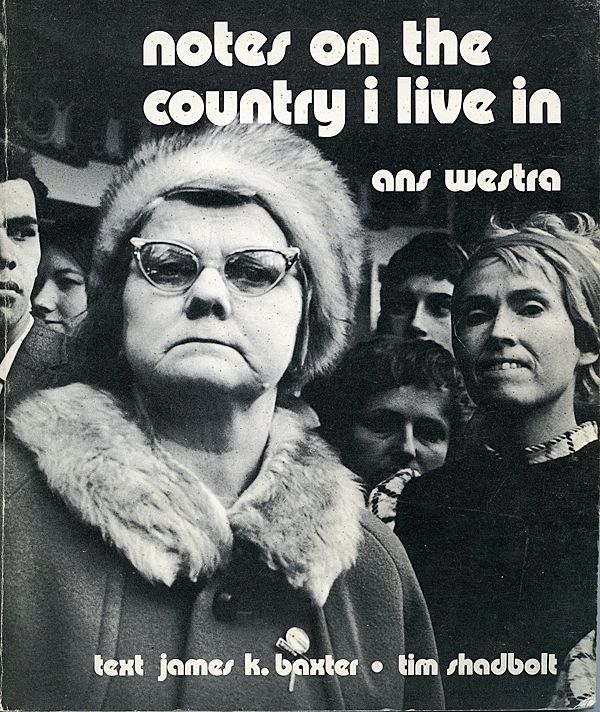

Notes on the Country I Live In

After years of searching through my parents' bookshelves for something, I realised this was the gem I didn’t even know I was looking for. Ans Westra’s 1972 collection of black-and-white documentary photography paints a rich picture of early '70s New Zealand. While the book spends time with cultural luminaries of the time, like James K Baxter and Sam Hunt, the majority of the characters are everyday people - young, old, urban, rural, Māori, Pakeha. The radicals and the enchantingly mundane. We see protests, we see sheep sales. We see communes and homes and rugby clubs and workplaces and we see extremely ordinary New Zealand shopping streets full of perfectly normal people. What characters! I loved it - I soaked up every picture and tried to peer around the edge of the frame to see more.

There is a glorious plainness in it that I found entrancing - Westra doesn’t sneer or look down on anyone in it, she is just there - everywhere it seems - to give us a window in. I took from this book, and still take, a deep respect for the so-called little guy, and a knowledge that there is beauty in the mundane.

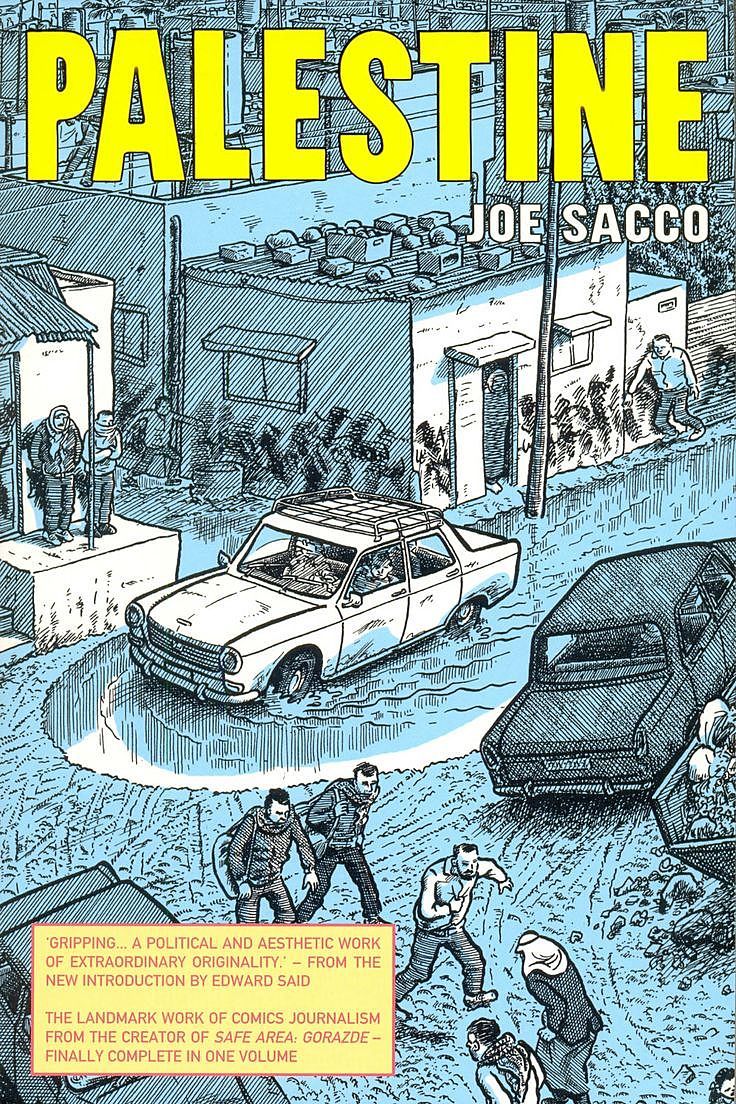

Palestine by Joe Sacco

Comics journalism? Comics journalism! Why the hell not? It’s perfect. Why did no one think of it before? The very idea made me love Joe Sacco before I’d even opened the book.

Palestine was the first of his that I read. Through detailed drawings, the stories of real Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip through 1991 and 1992. He spent time there, getting to know people, the history, the neighbourhoods. And it shows - there is such confidence in his material that he can let his drawing style vary wildly (often in the same frame) from cartoony exaggeration to lifelike documentation. He knows exactly when to emote and when to play it straight.

It looks like it must have taken him thousands of years to draw. As a result, and I think this is a trick that comics can pull in a unique way, he manages to simultaneously capture very human emotional storytelling and factual, believable reporting. We’re right there with the people. They come alive when he lets their arms flail like rubber or their eyes grow large like saucers while telling us a story, and then he knows exactly when to dial to back, using drawings packed full of details that give us the cold reality that hits double hard because we’re emotionally invested through the people: the bleakness of a bombed out street, or a simple leaky roof. And boots stepping around muddy puddles. There's a lot of stepping around muddy puddles.

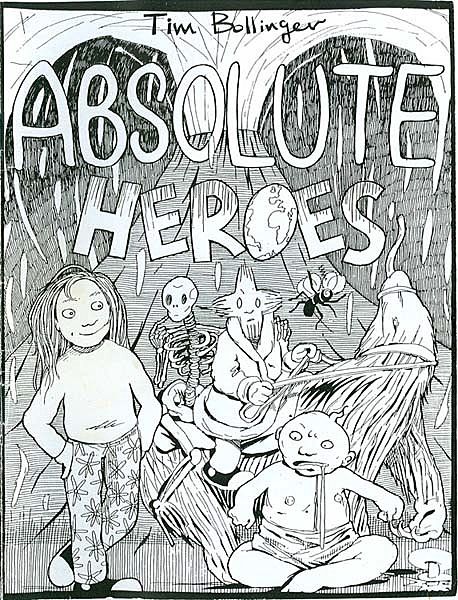

Absolute Heroes

Apart from Tintin and Asterix I never read other comics until well after I started making them. I thought comics were just terrible American superhero junk, so finding titles like Absolute Heroes, Dylan Horrocks’s Pickle and Love & Rockets by Los Bros Hernandez was like a bolt of lightning for poor little teenage me.

Bollinger’s Absolute Heroes just floored me: a wild and unpredictable story expressed in a lively, loose and almost punk drawing style, and, best of all, all told with a distinctly New Zealand voice! I still love the warmth and energy in it. You get the sense that the ideas are arriving faster than the pen can scribble them down, that the drawing is playing frantic, puffing catch-up to the wild writing.

Vehicle

I first discovered The Clean through the 90s covers tribute album God Save The Clean. I was 16, the perfect impressionable age, and it was HLAH’s raucous version of 'Beatnik' that lead me down the path. See you later, old me.

I got Vehicle out from the Library and it took about 20 seconds of opener 'Drawing to a Whole' to fall in love. The warmth! The life in it! The personality, the charm! It was inviting, and human. And compared to everything else I was listening to (this was the age of grunge remember) it actually made me feel good. And, of course, like Absolute Heroes, it blew me away that it sounded so unashamedly and defiantly kiwi. Not in a parochial, blokey tourist souvenir way - this felt real, and intelligent. In a literal sense the accent was unmistakable, but it’s also there, more deeply imbedded, in the whole tone. Much is written about the crudeness and looseness of early Flying Nun, and I certainly learned a lot about the value of imperfection, and the human touch, but The Clean on show in Vehicle is a perfectly formed unit. John Campbell said recently that Chris Knox and The Clean showed him how to be a “different kind of New Zealand man.” Well, me too.

Catch more of Toby's creative insights at The Kill Screen on the 17th of September at Q Theatre.