Living Taonga

Arihia Latham responds to Te Papa Tongarewa’s series Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho and the call to listen to keep stories of whānau, tīpuna and taonga alive.

I was back home at my marae last month. It’s a flight to Timaru and then a 45-minute drive south to the coast of Waimate. Waihao beach is a rise of musical greywacke stones. Their stories are ancient – I sat listening to the wind curl these pūrakau into my ears in whispers. The waves, crashing our power here, now. Back at the marae we are all reminded to stay out of the back paddock where the tohorā bones are buried – still curing under the earth. So, of course, all I can think about is the bones. It’s like they call to me in my dreams. We are here for a taonga pūoro wānanga run by my cousin, Ruby Solly. We are back here – her, me and my daughter – the day before everyone else arrives, and it feels like our place, but hasn’t always. Our marae doesn’t have a lot of taonga or carvings. Our hapū is spread far away and sometimes we forget it is our job to change the past for the future. We are changing that with these wānanga and creating a set of taonga pūoro to live here. We are helping to warm our whare with our voices, with our company, we are creating treasures for our uri to find in the future and wonder at their creation. This feels clunky sometimes. Mostly, though, it feels more and more like this is what our whare needs. It needs us to be here keeping it company, filling it with waiata and taonga and ngā mahara – our memories.

We are creating treasures for our uri to find in the future and wonder at their creation

Kahu Kutia (Tūhoe) has directed a powerful five-part series, Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho, as a resource for Te Papa Tongarewa, enabling us to understand the way in which our taonga are found, rescued, returned or stored. Quietly calling for our hands, our voices, our wairua to come back to them. Series presenter Khali Meari (Ngāti Rangi) is soft and strong in this role of showing the mamae and the magic of uncovering, and sharing how to access our taonga stored in museums and archives.

Quietly calling for our hands, our voices, our wairua to come back to them

Isaac Te Awa in Episode 1 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka

In the first episode, my whanauka Isaac Te Awa (Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Ngāpuhi), Curator Mātauranga Māori, opens the vaults of Te Papa to share some of the most amazing taonga kept there. He speaks about what is kept at the museum and the bias that exists there: “We see a lot of taonga that are collected in terms of mau rākau, weapons… we see a lot of beautiful whaakairo, we see lots of beautifully carved pieces of toki and pounamu. What we don’t see is anything to do with kids’ toys or wāhine. What that means is we are left with a collection that is already biased towards how Pākehā perceived us. So to try to tell Māori stories out of those taonga is the challenge.”

I want to see it swinging in the hands of rhythmic story, I want to feel the pūkana staring us down behind it

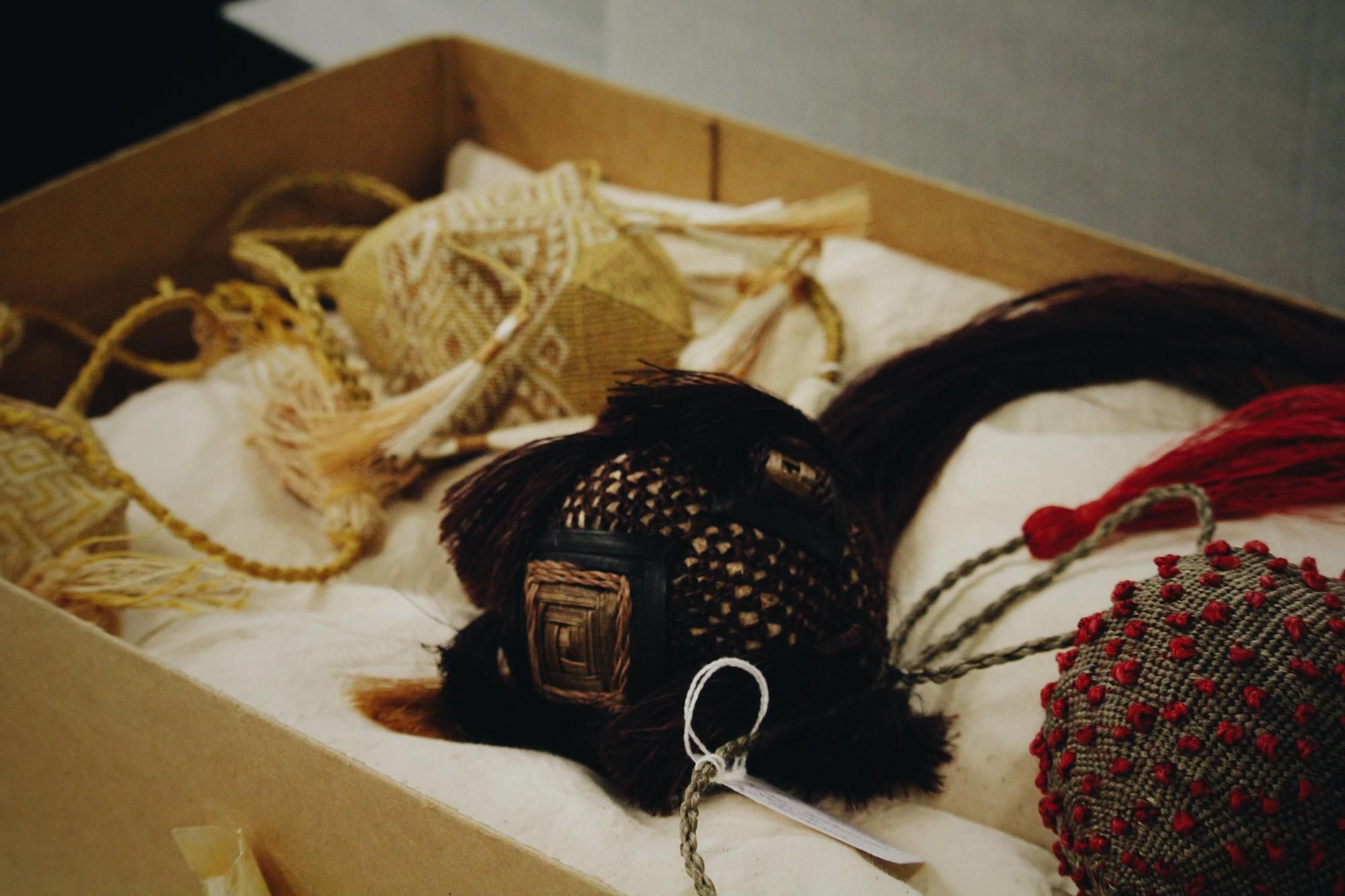

Te Awa’s role at the museum is a way to keep the door to our taonga open for artists and whānau to come and learn and reconnect with our traditional practices. He has a familiarity and lightness with the taonga, and speaks of them like whāngai children that don’t have known homes, and he is caring for them till they do. “To bring in practitioners, whānau, hapu and iwi who can use taonga to create their own art forms, to share their own kōrero and stories, it’s about bringing people inside the building and connecting with things that they’ve been so detached from. I think that’s what I love most about my job.” One poi made with the lace-like strips of houhere bark is stuffed with newspaper that shows its approximate age. I want to see it swinging in the hands of rhythmic story, I want to feel the pūkana staring us down behind it. There are pūtorino with intricate carvings and they are begging for the warm breath to give them a voice, but in the interest of their preservation, they are wahangū.

Poi at Te Papa in Episode 1 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka

This was one of the most exciting things about learning about and making taonga pūoro back home with my cousin. Her personal collection is so vast that we could just pick up and play and befriend the taonga that spoke to us. I felt like a tamaiti – wide eyed with wonder. My fingers and lips led me to the instruments that wanted me to play them. We found each other through the quiet of the wharenui, where my dreams were full of soundscapes. We greeted each dawn with our breathy learners’ sounds as te rā danced into the sky above the paddocks. Above our whale bones, the taonga sighed a mihi, and our marae was creaking with harikoa at having us there.

I felt like a tamaiti – wide eyed with wonder

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna in Episode 2 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka

In Episode Two, Te Whanganui-a-Tara jewellery maker Keri-Mei Zagrobelna (Te Āti Awa, Te Whānau-a-Apanui) shares her inspiration in recreating some of the traditional shapes and techniques. What I love about Zagrobelna is the way she speaks about the mauri of the taonga, about how mokemoke they are for company. She says she goes to keep them happy, she goes to listen to them. “Nan taught me how to talk to them and talk to objects, talk to taonga, talk to our tīpuna.” I think of all our taonga sitting in captivity around the world, and how few people would understand this concept that our taonga are living entities.

"I don’t own them. They are what they are and I am just a kaitiaki here to look after them."

Zagrobelna isn’t afraid to talk about her process of making as one that is led by the material, led by tīpuna, guided by the mauri of the piece as it comes into te ao marama. “I don’t own them. They are what they are and I am just a kaitiaki here to look after them, and then if they want to be realised into an object or made into something, that will naturally kinda come through, often sparked through inspiration of looking at the material that’s flooring it but looking at the whakapapa of the material, and then also seeing how our tīpuna might’ve used that material as well.”

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna and Khali Meari in Episode 2 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka

As I sat at the lagoon that forms the mouth of our awa and gathered uku and shaped pūtangitangi from our whenua, I felt this hard. The shapes and feelings were old to me. The shapes and feelings were new to me. My cousin picked up the clay orb and held it straight to her lips, the dark smear of earth marking her cheek as she played the sweetest note of return to the crashing waves cheering like a stadium of our tīpuna whose hands were dragged away from here. Those whose mouths became wahangū.

Khali Meari and Maimoa Toataua-Wallace in Episode 3 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka.

The third episode, in which Khali visits Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision and meets staff member Maimoa Toataua-Wallace (Ngāti Maniapoto), is a beautiful reminder of how our memories and taonga have many forms. There are so many stories sitting there unwatched, their own mauri needing to be tended to and seen, lest we forget. The ability to beam our tīpuna passed onto a screen is some freaky business, but it’s something most of our younger generation could riff off. Being able to hear the rangi of our reo, listen to the waiata and karakia. See the faces of our tīpuna and also witness the important events of the past as they happened. These taonga are living. Toataua-Wallace speaks of his hopes here: “Koirā te tino whāinga mōku te tino wawata mōku i roto i ēnei i ēnei tūmomo mahi. Kei āhei ngā iwi, ngā hapu, ngā whānau, te kitea i ō rātou ake taonga, ngā mea katoa.” That we can see and engage with the taonga of our people.

There are so many stories sitting there unwatched, their own mauri needing to be tended to and seen, lest we forget

Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision in Episode 3 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka.

Videography is now one of the most common forms of sharing and communication through social media. It’s a way for us to keep these stories alive across generations that might not consider coming to the vaults of a museum.

Amber Aranui and Khali Meari in Episode 4 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka.

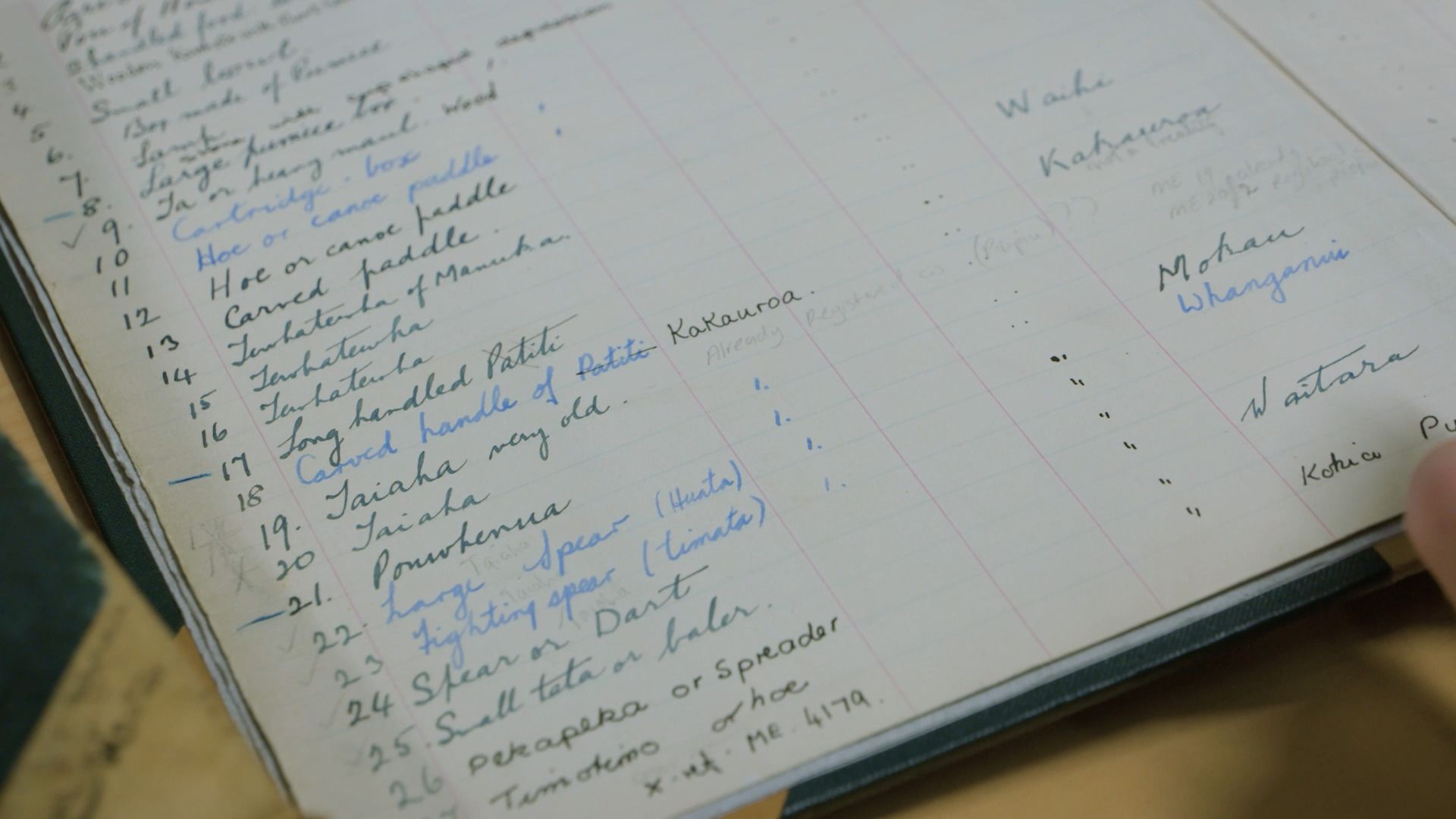

In Episode Four, Te Papa staff member Amber Aranui (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) speaks about her mahi with repatriation of our tīpuna and taonga from overseas. This mahi feels so important. Finding our tīpuna and taonga that were stolen or ended up overseas, and finding their whānau to take them home: “for us it’s about reconciliation, reunification and reconnection of taonga and tūpuna back with us that live today.”

"It’s about reconciliation, reunification and reconnection of taonga and tūpuna back with us that live today"

I loved the way she spoke about the museum as a safe halfway point. Never the end. The resting point is when the taonga get home. This feels such a relief in this strange meeting of past hē/wrongdoings with future aspirations to re-indiginise and hand the mana of our taonga back to the rightful kaitiaki. Hearing that our national museum sees themselves as a safe landing place, not a long-term home, feels like a step in the right direction, facing our past and moving into a future where our taonga can be kept company by whānau. I love Aranui’s hopes for the future: “I see the future of museology, particularly for our taonga, is that museums, wherever they are in the world, they relinquish that power, that power of the narrative, where it’s the museum telling the story of the people. Now it’s the people telling the story of the people, in the museum space.”

The museum as a safe halfway point...the resting point is when the taonga get home

Episode 4 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka.

In Episode Five there is a beautiful example of this – whānau caring for and holding the mana of their memories at home. Waitangi Teepa (Tūhoe, Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi) talks about being the guardian of written manuscripts of their whānau. Her role is Kaihahu Mahara: an exhumer of memories. The meaningful events and feelings shared are all kept and read through her careful curation. “This particular collection that we’ve got, this is the Hēnare Matua letters and manuscripts. They were written by at least 600 different tīpuna. But they are petitions, and they’re not only land petitions but they are petitions about mākutu, they’re petitions about adultery, about alcoholism. So, everything about life.”

Episode 5 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka.

The thread of speaking to our taonga arises again here and I love this kōrero about showing manaaki and spending time on whakawhanaunga with our taonga – whatever their form. Teepa says, “Like all taonga, you know, when you get your pounamu for the first time you’ve got to bond with it. I’d go into the stack room and I’ll be like ‘Mōrena!’ and then we’d have conversations. And everyone would be like ‘What are you doing?’ And I’m like, ‘I’m bonding, I’m bonding with my tīpuna. You fullas have to realise they haven’t seen anybody. I am the first human, living human, they have come across. I am going to give them the manaakitanga that we do as Māori.’

"I’m bonding, I’m bonding with my tīpuna."

I think of how we are all in a place of being Kaihahu Mahara at any given moment. Choosing to record our kaumatua on our phones, to take pictures and videos, to write stories or interviews. Choosing to make taonga and to use them, and keep their meaning alive in te ao hurihuri. Choosing to take them home. When I sat with my whanauka composing a waiata for our marae, the pesky thought of Who are we to do this? floated in at one point. But I realised, as the melody and oro of our very presence in our whare lifted with our collective voices, that this is exactly the memory I want this whare and our uri to hold. Not only do we have the role of keeping memories and taonga alive, we have a responsibility to set right the mamae of the past with our hopes for the future. When I cast my eyes around our wharenui, the sight of taonga shaped by our whenua, with the water from our awa, by the hands of the uri of Waihao, the kupu of our waiata becames the rongoā for all of the time our whare stands unoccupied, for all of our tāua and pōua that didn’t know this as home due to having our tikanga and reo beaten from them and their lives pulled to the cities.

Not only do we have the role of keeping memories and taonga alive, we have a responsibility to set right the mamae of the past with our hopes for the future

This series feels so timely with my own personal exploration with my whanauka back home. It makes me feel tau with my desire to sit in the back paddock and speak to the whale bones beneath. To tell them we are here. We are waiting for them. As we fossicked for small bones and taonga on the beach, it made sense to me that we listened carefully for those that warmed in our hands and asked to come home with us. I wish I had recordings of my tīpuna here. But I know that we can create that for our uri that are to come. It is up to all of us to listen carefully, to seek out and warm our taonga with our aroha. This is the call to keep our stories alive.

Episode 5 of Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho. Credit: Renati Waaka.

“You are it, so live it.”– Keri-Mei Zagrobelna, quoting her nan

Watch Ngā Taonga Tuku here. All five episodes are available to watch now.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership series with Kahu Kutia and Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand. Made possible through the Te Awe Kōtuku Mātauranga Māori Fund and the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.