On Literary Loneliness and Disclaimers*

*These are just ideas, not me writing on behalf of my entire race, everywhere.

“You asked me what it’s like to be a writer and I’m giving you a mess, / I know. But it’s a mess Ma – I’m not making this up. I made it down. / That’s what writing is, after all the nonsense, getting down so low / the world offers a merciful angle, a larger vision made of small / things, the lint suddenly a huge sheet of fog exactly the size of your / eyeball. And you look through it and see the thick steam in the all- / night bathhouse in Flushing, where someone reached out to me / once, traced the trapped flute of my collarbone. I never saw that / man’s face, only the gold-rimmed glasses floating in the fog. And / then the feeling, the velvet heat of it, everywhere inside me.”

– Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

When I first started reading Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous it was lockdown. I was making my way through a stack of books I panic-bought in the weekend when a potential lockdown hung heavy in the air. Getting down so low that we can see the world seems like at most times an impossible task, as well as the thing I feel myself failing at most days. Vuong gives us a letter to his mum. Writing about writing. He gives us poetry as novel. His prose helped me get down low, but my thoughts are still a mess.

My friend Rosabel said that sometimes writers articulate experiences you never knew you shared with anyone else. Taking anxious thoughts right from the silent pits of your mind and presenting them for you, as if they know you. Reading those words fixed on a page can be like unlocking parts of yourself you’ve never paid attention to.

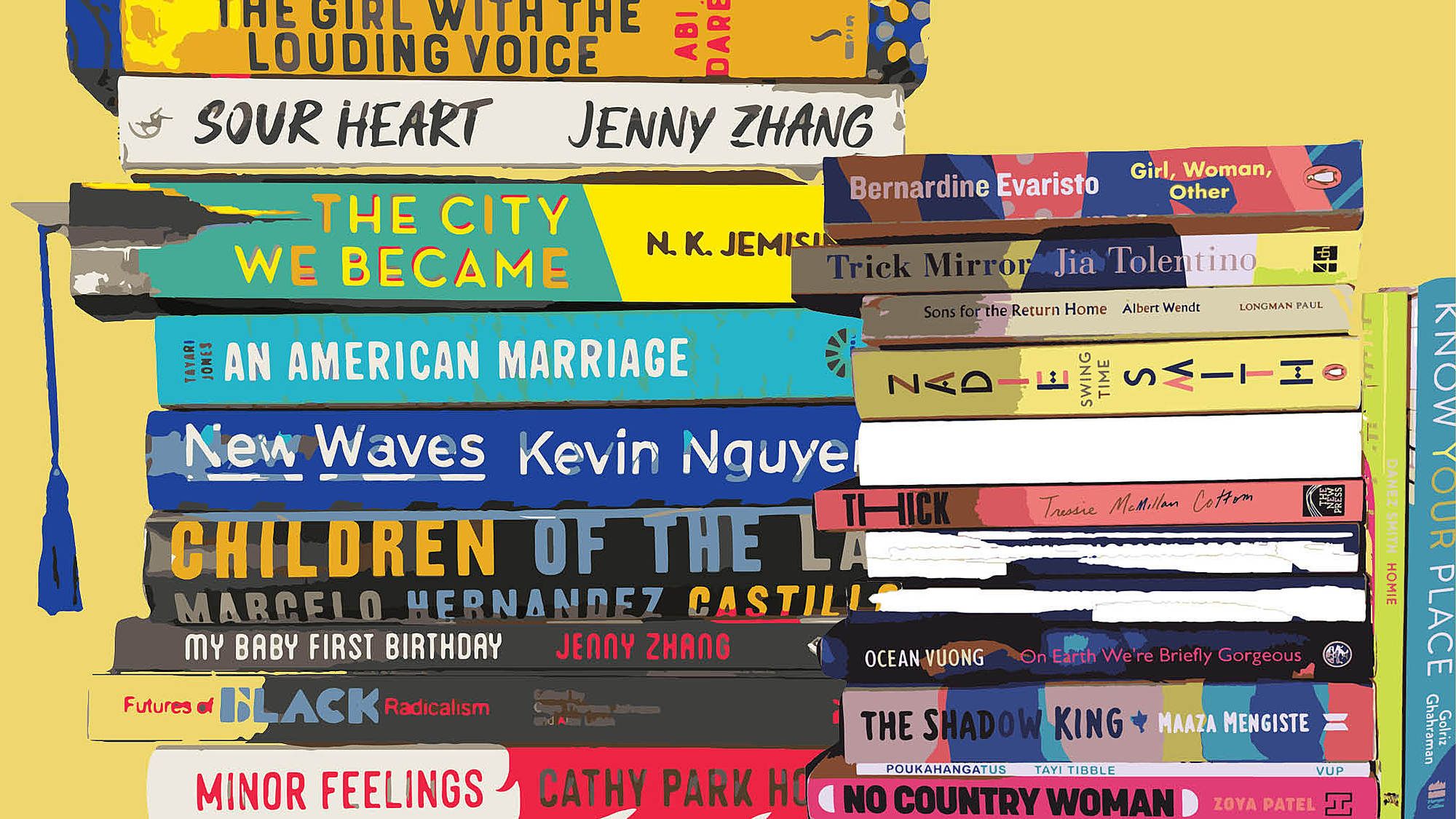

I try to buy a lot of books. I understand royalties. And like to think about my coins being dropped directly into the authors’ pockets. I think about two things when I choose what to buy: the cover (I can’t help it, I’m art-school trained), and making sure they’re stories by BIPOC writers – regardless of genre. I read On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous somewhere between Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion, Danez Smith’s Homie and Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other. All of which sat on my nightstand with some other well-loved global and local friends to keep them company.

I always longed to be a part of this global BIPOC community of authors ... then maybe I wouldn’t feel the pressure to be all things to all people at all times.

In lockdown, I lay on my side and looked at the pile of books. I saw diasporic experience stacked on top and on top of itself, like a stack of my own longing for echoes of a similar experience to mine. Looking at this stack, I saw books that, in concert, create a collective literary assemblage. A stack of books that, despite the weight of history, don’t need to do the heavy lifting but rather allow for nuance, poetry and cultural specificity, simply because of their collective mass; because of the simple reason that there are many of them.

I always longed to be a part of this global BIPOC community of authors, because I thought that then maybe I wouldn’t feel the pressure to be all things to all people at all times. Maybe I would be able to not write about race and not have my work packaged that way despite my resistance. And maybe, just maybe, I would actually know what I wanted to write because I would have the freedom to know my own mind outside a constant and relentless balancing act.

As I read more and more of this work, I also started to no longer see myself in the words because I saw them, the authors, their cultural specificities and the things that make them uniquely them and not me. I realised, like a baby bird waiting with its beak and throat open for its mum to regurgitate worms, that I was being eagerly fed by global BIPOC books – mostly from everywhere except here. And when they are from here, mostly by non-Pacific BIPOC authors. Looking at my nightstand, at the depth of fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry and theory by BIPOC writers from the US and UK, I suddenly felt lonely. While the words of non-white writers from the US and UK have been a lifeline for a long time, I hadn’t even realised that the mum feeding me wasn’t my own.

*

“… as we sit trapped in the nightmare, we are well aware that it is happening to us.”

“The reality is that marginalised identities are both ours and imposed. We live our lives, interacting with the systems out there in the world, from the prism of our races, our genders, our manifested religions, and our sexualities, whether we want to or not.”

“Majority identity holders get to interact with the world as individuals seemingly devoid of group identity.”

“It turns out that only the perspectives of the less-advantaged identity carriers are dismissed as ‘identity politics’.”

– Golriz Ghahraman, Know Your Place

I can hardly make a comparative argument between my own experience as a writer and that of Golriz Ghahraman, an amazingly ferocious MP who faces constant abuse and threats, but I feel her words deeply when she writes about all the things that she balances. She’s not simply ‘a politician’, she’s the first refugee politician of New Zealand, a burden that won’t go away until she’s not the only one.

The reading I did during lockdown made me reflect on the pressures I feel in my own writing. That stack of books was marked by writers who had authority over who they would be. Or maybe I’m just insecure in comparison. They seem to me, at least, to be people who don’t think about the balance that I find paralyses me. Or they at least push through it.

The more books I read, the more I realise that I don’t know what the difference is between my writing and me writing disclaimers.

Editors and academic supervisors always tell me that I qualify myself almost apologetically. One supervisor told me that there is a fine line between humility and self-degradation, and that self-degradation isn’t cute. When I wrote False Divides, I wanted to be really clear that I was “writing from my specific vantage point of the Pacific Ocean”. I wanted to be really clear about that because I didn’t want my ideas to be taken to be more than they are: just ideas. But by the third inclusion of the same phrase, my editor had to tell me to stop. I think the editor’s sentiment was along the lines of, “we get it, it’s your book.” And yet still it was held as more than it is.

In feedback on a recent piece I wrote for Pantograph Punch, which I later killed before it could see it the light, my editor commented that it’s interesting how much I seem to preface everything I write – that I would take a paragraph to qualify myself before making my actual point. Basically, I seem to be obsessed with disclaimers. Sometimes my writing, on closer inspection, is 2000 words of only disclaimers.

It feels so natural that sometimes I don’t even know I’m doing it. But the more I think about it, the more I realise I have always qualified myself, my writing and ideas because I’ve felt I had to. I can’t just say an artwork is racist, I have to qualify why it is, so that I know, and you know, there is no doubt in the matter. I can’t just share a feeling, I have to rationalise it so that I don’t get called an emotional woman, I have to intellectualise it, so I don’t get called an irrational brown woman.

*

“… I found that I could hardly trust anything that I was thinking. A doubt that always hovers in the back of my mind intensified: that whatever conclusions I might reach about myself, my life, and my environment are just as likely to be diametrically wrong as they are to be right. This suspicion is hard for me to articulate closely, in part because I usually extinguish it by writing. When I feel confused about something, I write about it until I turn into the person who shows up on paper: a person who is plausibly trustworthy, intuitive, and clear.”

– Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion

I read Jia Tolentino at the same time as Rose Lu’s All Who Live on Islands. Both books were striking to me for the way that they said everything and nothing about identity all at the same time. I still struggle with working out if it’s just about making a conscious decision to write what you want or it’s about strength in numbers. And if it’s just you deciding, yourself, how do you even work out what is your interest and what is external pressure? How do you write for you when you also write for a public?

I think I’ve always overcompensated because, in retrospect, I’m lonely. I come from visual arts – a large community of Pacific makers who are all my age and who have all had experiences like mine, and where at any given time there is a yet-to-be-seen exhibition of Pacific art. And I’m now trying to find those same people in literature, and on that ‘local’ table at Unity Books. There’s a feeling that when there are more of us, we’re all that little bit freer to be who we want to be. And not who everyone else tells us to be.

It is precisely strength of numbers that will unburden us

There is of course a wealth of Pacific literary masters – poets, theatre writers, scholars and novelists –whose words have wrapped around me for years, like a tiger-print mink blanket the weight of a small child. But they are my elders, not my peers. They are people who have laid pathways for me but are not walking alongside me. There is, too, a scattering of Pacific voices my age or thereabouts – poets, theatre writers, screen writers and scholars alike – people whose words are published online, on platforms like this one, or who sharpen their literary prowess in 280-character tweets. Like chocolate chips in an XXL cookie. But still I often feel lonely, or like the lone Pacific voice for any given thing at any given time. And so no matter what I write, it will be taken to mean more than just my ideas. No matter how many disclaimers or prefaces I write.

Being a part of those literary communities overseas, even just as a reader, can fill that gap for a period of time. Yet, ultimately, it’s not quite enough. I begin to see that this big amorphous ocean of BIPOC misses the specificity that makes us uniquely us and that places us uniquely here, and it is precisely strength of numbers that will unburden us. Or I maybe I just need to unburden myself. Until that happens, I will continue to be nourished by these other literary communities, including BIPOC literary communities here that aren’t quite my own, and I’ll continue to be lonely. I think, if I’m honest, I’m just keen to make some friends, on the page and off.