Building the Community (Archive): The Work of Linda T.

Thinking of art as koha, the serious and invaluable work of Linda T..

Thinking of art as koha, the serious and invaluable work of Linda T..

Don’t ask me why I like art.

I don’t like art; I just think about it, engage with it everyday.

It helps me to build and complete works by engaging with different media.

It gives me methods to tell stories in a multitude of ways.

I don’t like art; I love it.[1]

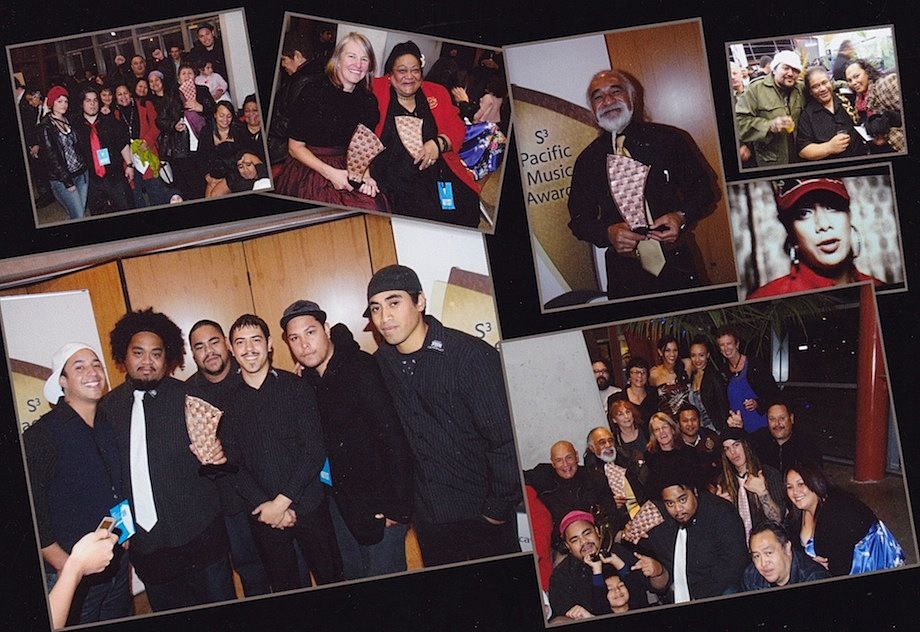

For decades, Tuafale Tanoa’i — known to most as Linda T. — has been a presence in arts and activist communities across Tāmaki Makaurau. She has been to countless music gigs, exhibition openings, protest marches, plays, lectures and public programmes. For all the event’s she’s attended, Linda T.’s likely been involved, most notably as a photographer and DJ, in just as many. As a text for Artspace’s new artist show in 2008 put it, “She is the scene and she’s been gigging it for a while."

It’s easy to confuse Linda T. the supporter with Linda T. the artist. In fact, there’s little difference between them. There’s a definite blur between social activity and making activity within her practice. This is partly because Linda T. is not only an active participant in her overlapping Māori, Pacific and LGBTQI+ communities, she’s constantly documenting their activities and stories too.

Don’t ask me why I have made the range of stories that I have.

Most of my recent works are snippets of my every day.

They are moving image shorts of art openings, community poetry sessions, artist talks, art works, private family gatherings, memorials to people whom have had huge lives, lectures by people I admire, community housing events, artists analysing art exhibitions, book launchings, performance installation works and music videos.

I am creating my own version of reality television

A couple of months ago, Linda T. opened her solo exhibition, Story Telling As Koha (STAK) at Studio One Toi Tu in Ponsonby. The exhibition gave a small glimpse into the sheer breadth of Linda T.’s collection of photographs, sound recordings, and video interviews. There are prints and video footage of a waka expedition, a filmed interview of a neighbour describing the plants in his garden, and a slideshow that flicks with nonchalant ease between black and white photographs of political marches in the 1970s and 80s to sepia-toned images of students in school uniforms standing next to a taxidermy elephant.

STAK offered only a sliver of Linda T.’s archive. She has containers upon containers of dvds, cds, records, photographs, notes, and unprocessed film in living space. And that’s not even close to all of it. She still struggles to pay for a commercial storage space where the rest, and the bulk, of her archives reside. The exhibition did though significantly give a glimpse of some of Linda T.’s earlier documentation. Known mostly for her installations from the late 2000s, STAK was the first time I saw Linda T.’s earlier material and the activism that it documented.

Looking through those earlier records, I was surprised by how young Linda T. was in many of the images, and how early she and her friends became involved in political action. “Due to the abuse that lots of people were going through, we had no choice as young people but to deal with it”, explains Linda T.. “We wanted our younger siblings and those coming in behind us [at school] to have somewhere to go to, to have a clearer path. We had to create those bridges or find the resources, and probably the language - we needed to make it safer in general.”[3]

Don’t ask me why I look at notions of identity, class, gender and sex.

They are everyday issues.

Having the power to define these issues produces social power in our present world. (Smith:2006)

Also because I can and I feel like I have to.

Growing up in 1970s inner-city Auckland, safety was understood in its most direct terms. For Linda T., the tool of survival was community work. As a gay, New Zealand-raised Samoan teenager at Auckland Girls’ Grammar, Linda T., with her friends, became active in either creating or referring to resources for victims of abuse. They directed people towards supportive and resourceful community people in Maori Affairs, the Race Relations Conciliators office, Rev. L.I. Sio of Newton church in Edinburgh Stree, rape crisis and self defence. They also joined the Māori Women's Welfare League and listened to guest lectures by educator Louisa Crawley and P.A.C.I.F.I.C.A (Pacific Allied Womens Council Inspires Faith in Ideals Concerning All) founder and president Paddy Walker on Pacific women’s rights. “We were around lots of cool women, who were working within their own communities, they were working for our communities,” says Linda T.. “Us being part of those bigger organisations created a whole lot of learning for us.”[4]

Linda T.’s archive functions, partly, as a record of some of those learnings. The images trace Auckland Girls’ Grammar students as they undertook a range of activities, from lobbying for a whare wananga to participating in Polyfest and attending Black Women’s hui. Often, the same figures show up in later images. Linda T.’s material records a loose, amorphous coming together of people who were carving out cultural spaces, championing indigenous knowledge and encouraging safe practices.

Don’t ask me why I can’t remember what I did last week.

Memories are created with my camera. I’d have to check my files.

I am thankful that when I awaken that I remember my name, my identity, my cultural up-bringing and who my family and friends are.

In 1988, Linda T. suffered unexplained bouts of amnesia. She was unable to remember most details of her life, and many details about herself. Though short-lived, the occurrence exacerbated what was already a tendency towards fervent documenting and hoarding. Her archive then, also, functions to record that which might be personally forgotten, and nothing escapes her camera. There are wedding photos, music gigs, recreational events, catalogued right next to the political gesture is the prosaic moment, all captured with the same level of dedication and intent.

Everyday is Mother’s Day (2014 onwards) is an ongoing series of photographs capturing Linda T. and her mother Ema Tanoa’i as they go about their days. Collectively, they show the range of places that Linda T. goes with her mother, suggesting a care to engage with her at all times. Individually, the images hint at a gradual loss. Ema has dementia, and the photographs act as clear tools of trying to record and trying to stay active. They are some of Linda T.’s most beautiful and poignant works.

Don’t ask me why I like to tell stories.

I don’t like to tell stories; I just think about it everyday, in different ways.

To help create histories that link the past to the present.

To help to re-address colonial issues and to feed into decolonising minds

I don’t like to tell stories; I love it.

While Linda T.’s archive captures moments that are inseparably personal and political, it’s also an ongoing investigation into what it means to share those memories. Inspired by the work of seminal filmmakers Merata Mita, Barry Barclay and Sima Urale, Linda T. is critical of mainstream filmmaking processes and their monocultural exclusion of minority voices. Working against the modes of studio production and a capitalist distribution mentality, Linda T. aims to break down the individualistic production of media, and the exclusion of viewers from the making process.

Don’t ask me why I question western methodologies.

I don’t like it but I question western methodologies everyday, in angry ways.

It enables me to address a ‘politics of difference and otherness’ (hooks, 1990)

It highlights imperialism, critiques notions of ‘identity for oppressed groups’.

(hooks, 1990).

It forces me to look at my ancestral knowledge and my numerous roles in the present and future.

I don’t like to question western methodologies; it creates more work for me,

I dislike that intensely.

In his seminal lecture ‘Celebrating Fourth Cinema’, Barclay puts forward Fourth Cinema as a descriptor of Indigenous Cinema – a type of cinema that is driven by an allegiance in indigenous cultural values that precede and persist within the construct of the nation state. As such, it’s concerned less with surface features or visuality, and more with the ways in which that cinema can accentuate indigenous cultural value. Within Maori cinema, Barclay cites whanaungatanga, wairua, or aroha as some values that could inform productions. Technical finish is of secondary concern, and is in fact a slippery step on a path into complicities with mainstream orthodoxy.

Linda T. similarly places primary value outside of aesthetics. She instead strives to follow a methodology grounded in the concept of ‘koha’. At a fundamental level, Linda T. follows this through by gifting her work – usually in the form of a burnt DVD – back to those who helped make it. More expansively, Linda T. creates installation environments that are designed to put people at ease. The equipment she uses is often low-fi and familiar; CRT box TVs, VCR players, VHS tapes, video cameras, projectors, cd players, headphones. It’s technology that we know, and know from our own domestic environments. It’s also the most economical choice. Being borderline obsolete, or at the very least, not the latest high-tech equipment, older technology makes it cheaper for Linda T. to present things en masse. There are always multiple TVs and her images are often tiled to maximize the number of images per sheet. It’s unlikely that minimalism will ever be a value in her approach to installation (or in her archive). Generosity is much more important.

Don’t ask me why I use ‘koha’ as a work methodology.

It is part of a concept of giving, addresses notions of affordability and being accessible and exclusive.

It’s a way of life.

It addresses my alternative culture politics.

Editing is in fact close to non-existent in Linda T.’s work. In part, that reflects her belief that content is the primary purpose of the recording, not technical mastery. It’s also an active decision to refuse to shape the content that ultimately is the korero of other people. Consequently, there are many moments in . T’s videos that feel clunky, like an adjustment of a tripod mid-filming. Leaving the data raw is also an acknowledgement that the content is never finished; it’s always being adapted into new compilations, or grows with the addition of new recordings.

Don’t ask me why I use performance installation art.

I find it exciting and interactive.

It’s painful and pleasurable.

It is inclusive and exclusive.

For me it is a realm that is ‘instantaneously planned spontaneity’. It’s unique and only happens once.

Linda T. presents her archive selections as ‘performance installations’. Alongside designated ‘viewing zones’, Linda T. often creates lounge room-like ‘sets’ where people are invited to be interviewed or perform in some manner. This new material is then either looped back into the installation as a live feed and recorded to enter into the archive and feed into future exhibitions. One particularly charming example is the ongoing project ‘dancing feet’, where audience members can dance on a designated stage in front of a camera pointed at their feet, while simultaneously seeing their feet projected in real time on a wall or playing on a monitor. The effect is democratising, breaking down the zone between passive viewer and stolid object, to create a space of fun and participation. It’s impossible to describe the warmth of the installations without acknowledging the warmth of Linda T. herself. Her presence doubles as host, and consequently her live projects always feel inviting.

Don’t ask me why I highlight indigenous intelligence.

To empower my learned and lived experiences, acknowledging my extended family and our authentic ancestral knowledge.

I feel that this ‘society is based on lies, on untruths, on hallucination’ (Sontag:1999),

on fabricated colonial histories. (Turner:2005)

I believe indigenous knowledge to be true.

One of Linda T.’s longest projects is LTTV, a makeshift TV ‘lounge’ where a number of guests are interviewed and recorded on video. In media, choosing who gets to speak is an inherently political decision, because it involves choice: who gets to speak inevitably means also choosing who doesn’t. Undeniably, there is a strong Pacific and Māori lean in Linda T.’s selection of interviewees. A glance at the title of her video compilations shows multiple DVDs featuring the Merata Mita, the poet and activist Rev. Mua Strickson-Pua, musician Tigilau Ness, as well as innumerable Pacific art compilations and Pacific artist interviews. Though the guests are carefully chosen, the interviews are not pre-planned, and they take on a sprawling and spontaneous path.

Don’t ask me why I seem to be exclusive.

It empowers my own communities.

It encourages consciousness-raising aspects to my different narratives.

It creates boundaries and bridges that can privilege some voices by denying others.

It is a performative act, which offers space for change and spontaneous shifts between my cultural identity and

western paradigms.

It helps me to look at better access to knowledge.

It’s difficult to separate Linda T.’s performance installations from her work in the intergenerational arts collective, D.A.N.C.E. Art Club. Recently, they undertook a legendary attempt at breaking the Guinness World record for continuous DJing in a public space. Like Dancing Feet, the work was dependent on audience engagement; a key caveat of the record is that two people must be dancing at all times. The call out for dancing volunteers created a swell of invested people, with the dancing linked to an online live stream for long-distance supporters.

Don’t ask me why I love to dance.

I enjoy the sense of freedom; my mind relaxes into a different zone.

I feel free from universal conversations and worldly interactions.

I feel free from social constraints.

D.A.N.C.E. art club projects and Linda T.’s individual practice share a belief in working on a local rather than mainstream broadband. Perhaps one of the most indicative projects of D.A.N.C.E. Art Club’s inclusive spirit is D.A.N.C.E FM 106.7. The collective took a mobile radio station around Taupo, meeting and broadcasting with communities in the region. In an essay on D.A.N.C.E. FM 106.7, curator and critic Mark Amery talks about hosting as a DJ term that could apply equally to the style of D.A.N.C.E Art Club’s practice. Rather than authoring content, D.A.N.C.E. FM 106.7 encouraged people to speak and listen to each other. Linda T.’s art practice operates in the same way. Her installations don’t just represent communities – they actively nourish communities, providing a safe space that, even if just for a moment, holds and supports people in coming together.

The danger of an inclusive, participatory, people-focused arts practice is that it can get tagged as a-critical. That an indifference for technical aesthetics is read as hobbyist, or that a lack of editing gets confused for a lack of discernment. To do so would fail to acknowledge that these practices deliberately eschew modes of production and aesthetic values that have historically propped up monocultural media. Linda T. still operates from a need for the basic safety of her communities. She moves away from traditional conventions of image-and exhibition-making in the full awareness that the traditions of selection, editing, and even slick aesthetics have served to disconnect minorities from their stories. Instead, the social is both her subject matter and her methodology. Her works defy an easy assessment because they are circular and grounded in conversations: participating in them, recording them, performing them, all in a loop. With supporting her communities in mind, Linda T. sidesteps mainstream practices, and creates a whole new way of doing things that is idiosyncratically her own

Don’t ask me why I don’t have a favourite movie.

I haven’t made it yet.

[1] Linda T., The Auto-interview, 2007-ongoing

[3] Personal correspondence, July 15 2017

[4] Personal correspondence, July 15 2017