Lee Mingwei on Creating Acts of Kindness

Rosabel Tan talks to Lee Mingwei about forging connections between strangers and the stories behind his works.

Rosabel Tan talks to Lee Mingwei about forging connections between strangers and the stories behind his works.

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

From Kindness by Naomi Shihab Nye

Lee Mingwei’s works are icebergs. Deceptively simple, they contain multitudes below the surface: ideas and moments merely hinted at, or untold, ready to be broken open. Some of that is inherent in the work; some of that is inherent in you. And while there are labels that elucidate his practice (relational aestheticism, participatory art) and his identity (Zen Buddhism and his ‘Eastern perspective’), none adequately capture the exquisite and joyous intimacy his work creates.

The 52-year-old Taiwanese Aboriginal has spent his career forging moments of connection, including major exhibitions at Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Mori Art Museum, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the Venice Biennale. His first solo show – which took place at the Whitney the year after he completed his MFA in 1998 – featured two works: The Letter Writing Project – which invited visitors to send letters of gratitude, insight and forgiveness – and The Dining Project, which saw strangers entering a lottery to have dinner with him in the Gallery each night. Random selection saw him cooking dinner for a wide range of guests, including “a 12-year old girl, a grandmother in her 70s, a tourist from Milwaukee, an editor of pornographic magazines, a Pakistani taxi driver who had been an art historian before coming to New York, and a bulimic who wanted to participate in the work in order to confront her illness.”

“People often mistake me as a female artist,” he tells me, because his first name – Mingwei – isn’t gendered, and because his works involve everyday domestic events, transformed into moments of potential: cooking and sleeping are no longer functional activities, but opportunities for human vulnerability, admission, emotion and beauty. They’re moments that feel more important now than ever before: acts that create space for empathy with people we know, as well as people we’ve never met. As a political work, it’s unassuming – quiet in the way that kindness is quiet. It never announces itself boldly, but invites strangers to reveal their best selves, exposing its own faith and optimism in the world in which it sits.

His works involve everyday domestic events, transformed into moments of potential: cooking and sleeping are no longer functional activities, but opportunities for human vulnerability, admission, emotion and beauty

It also invites an understated radicalism, and what’s especially striking about the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki exhibition, Lee Mingwei and His Relations: The Art of Participation, is the way it positions the artist firmly within the world. It actively rebukes the myth that art is a divine act of magic, instead exhibiting his influences – both personal and artistic – which gives the show a kind of balance, with the artist in the middle: preceded by his influences, completed by his visitors.

The following interview took place in two settings the day before the exhibition opened: in the unfinished exhibition space (where he’d occasionally pause to inspect minor details, like a missing stroke on a piece of translated wall text) and on the balcony of the Gallery cafe overlooking Albert Park.

Mingwei speaks with a soft and melodic American accent, and with an open smile that invites instinctive trust. He joins most of his sentences with ‘so’ and ‘and’, as though every thought necessarily leads onto the next and he speaks with sentences arranged in ways that feel more intuitive in Asian languages, giving his observations an off-kilter familiarity where time occasionally slips into present tense before returning to the past.

RT: Your grandmother has had such an influential position on your work. What was she like?

LM: I’m partly Taiwanese Aboriginal – from a group called the Pingpu tribe, and we’re matriarchal so we’re closer to the women in the family. My maternal grandparents lived in a town called Puli, and during summer vacation, my parents would drive us back and we’d spend about a month living with them.

My grandma had a clinic, which is unusual for a female doctor, and I remember the Han Chinese doctors didn’t want to have anything to do with the Aborigines, but my grandmother making a point of saying, 'No, everybody is equal when they come to my clinic.' I remember some of her patients would come in with bow and arrows, and tattoos on their face, and I remember they didn't use money for exchange, so they brought animals they hunted from the mountain in exchange for my grandmother's service.

When she retired, she would wake up early in the morning and make porridge for anybody who wanted to come and have food. Sometimes they weren't homeless, but were workers who didn't have enough money, and they would line up and she would be outside [her clinic] ladling the porridge.

She was very austere. She wasn’t what we think of when we think of a grandmother. Being a female doctor, she had a strong personality and she knew what she wanted. She knew how children should behave. One of those tiger grandmothers.

I was living in San Francisco when she passed away. There were a lot of things I wanted to tell her, so I wrote – over a year and a half – 120 letters to her. But of course there was no place I could send them. Some of the letters were simple – just feelings – and some were three or four pages. Some were just drawings. At the end, I burned all of these letters, as a way of sending them up to her.

The idea [with The Letter Writing Project] is that people can go in and write letters of gratitude, forgiveness and insight. You can address your letter and we’ll send it out for you, but you’ll notice that most of these aren’t sealed. When they’re not sealed, you’re encouraged to read the contents.

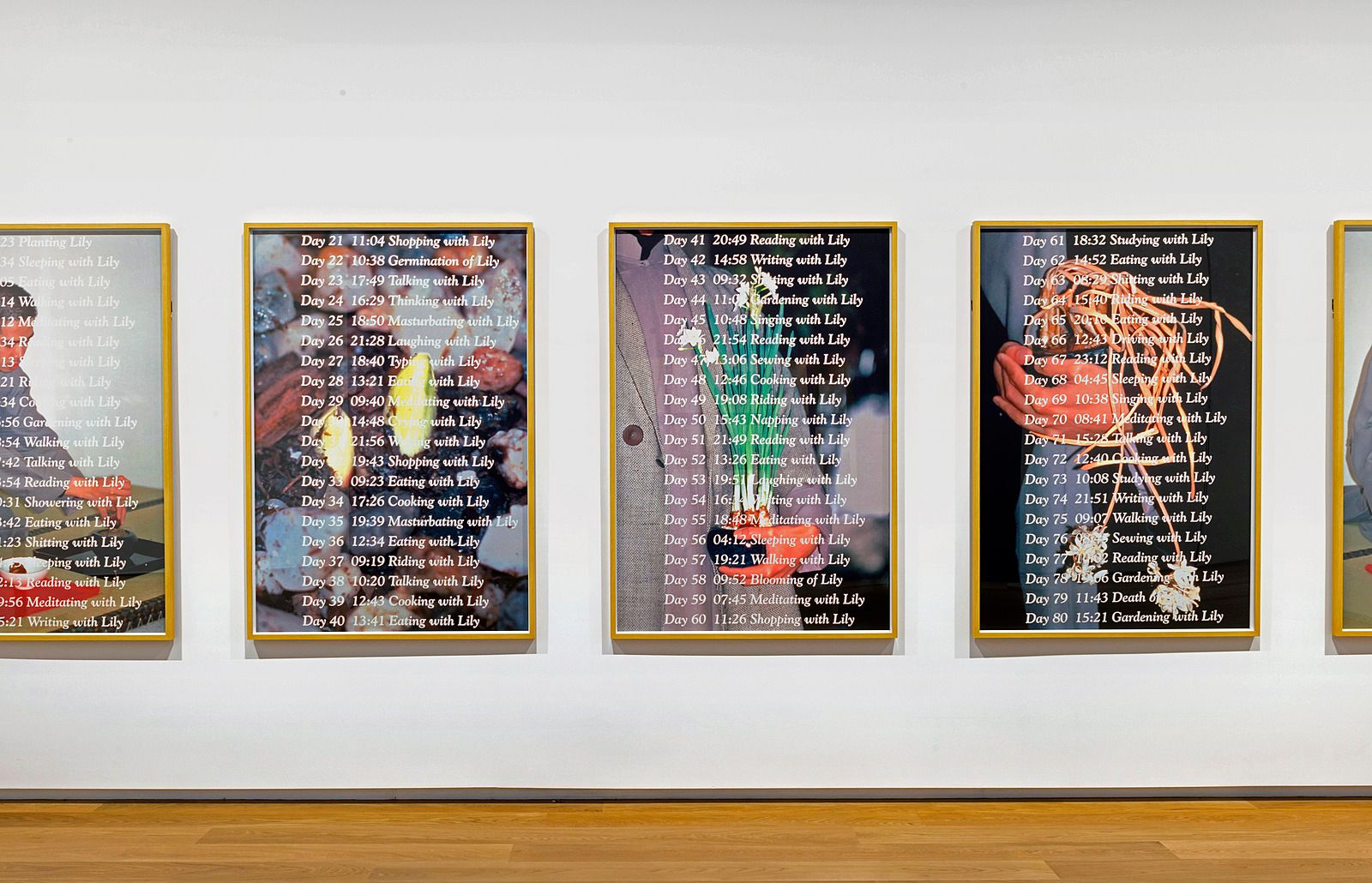

This is The Sleeping Project. This is my work [points to the beds and the surrounding nightstands] but not these [points to the surrounding artwork hanging on the walls], but they’re part of the show.

Visitors can fill out a card to sleep with me or one of the participating staff. There are dates you can select, and a week before each day, we select a person to share a night with us.

The idea came from my experience of riding a night-train from Paris to Prague. I was sharing the compartment with a Polish gentlemen, and he told me how his whole family went into Auschwitz and how he was the only person that survived. So after three, four hours of this very intimate conversation, he went to bed. And I was 17 - I didn't know what to do with this very complex story and feeling. So the origination of the project came from that seed, though of course at that time I wasn't thinking about being an artist, I was thinking about being a biologist. It wasn’t until 2000 that The Sleeping Project came to real fruition.

When each person arrives, they bring something they usually keep in their sleeping area and leave it with us [walks over to the nightstand sitting next to the left bed] This is mine. This is where the host sleeps, and this is what I have in my bedroom.

This is a book I always carry with me – 魏晋小说大观 (wèi jìn xiǎoshuō dàguān). Basically it’s a collection of 3rd and 4th century 小说 (xiǎoshuō) or essays documenting what the writers saw around where they lived [stops on a page]. These are 符 (fú) which - what is it in English? - it's not even a word, it's a kind of spiritual device. A spiritual diagram that you put on a piece of paper or board when you climb up the mountain to ward off any bad spirits.

Gradually all of these nightstands will be filled, so it's quite experiential in terms of an exhibition.

And this is The Mending Project. Every day there will be a mender, waiting for someone to bring something for repair. It’s a gradual, progressive project with very visible, bright mending,

Can you tell me a little about the story behind this project?

Yes - it was 2000, and 9/11 happened.

My partner’s office was in the north tower, which was the first building the aeroplane hit. Luckily, we were swimming that morning and he was late – by five minutes. He literally saw the airplane fly into his building. He said it was the darkest hole in the sky, and everything unthinkable started falling from that black hole – bits of the aeroplane engine, shoes, people, seats, purses, heads, all of it started falling.

He said it was the darkest hole in the sky, and everything unthinkable started falling from that black hole

We didn't have contact with each other for about five hours. I thought he was dead. He had started running uptown, and finally he found a phone that was working. And when he came back - I basically got everything from our drawer and started mending socks, and underwear, and pants. Subconsciously I think I knew something was wrong and I needed to repair, but I couldn't repair anything else.

It took me about nine years to really process that very highly charged moment of our lives and make it into something more poetic. That's how The Mending Project appeared.

It’s such an incredibly huge moment for this project to come from. It’s unnerving how such a small encounter can change everything.

I know! I remember him calling from his office around 10pm the night before. He didn’t usually stay so late, but it was stormy outside and he couldn’t get a cab.

When he called, he said, 'Oh listen to this', and I remember his office door was going 'eeehhhh' [he makes a creaking sound] because their building was swaying in the storm, and the door was closing and opening, closing and opening.

And when he came home, we had this conversation. We had been dating for about six months at that time. And I remember lying on the sofa, around midnight, and he said ‘I don’t want you to go first. It’d be so sad. I’m not willing to take on that sadness. I don’t want you to go first.’

That was the first and only time – we never had that conversation again. And it was so weird, because within eight hours, this thing happened.

That changed everyone's lives. That changed everything.

Your work strips back these complex, momentous, difficult experiences into small and simple shared acts, and so much of them tie into this idea of a gift.

It makes me think about my own mother. I don’t know how you’d define closeness, because in my family and I think in Singaporean Chinese culture in general, you don't talk very much. So we don't talk much, but when I was young and growing up in Brisbane, they sent me to a private Lutheran school. We didn’t have much money so this was a big deal, and my parents made a lot of sacrifices in order to send me there, and I remember the two years I was there – before we moved to New Zealand – my mum would spend the whole year hand-crafting these objects. One year she crocheted little soap covers, over and over and over again. And the next year she made these photo frames using fabric. And she’d make enough so that I could give a gift to everybody in my class.

[Nodding] Yeah, yeah, yeah, yup.

It’s interesting, because it was her way of expressing her love, but it wasn’t focused on me – it was focused on me and my place in this world.

And it’s a way of saying 'Please accept us into your community.' I remember something very similar when I immigrated to San Francisco. And my mother - she didn't make things. She catered - so she asked the bakery next to our house to bake these beautiful cakes for my first day of school, to give it to everybody. Similar idea. ‘Don't hit my child.’

How did you find moving to San Francisco? What was that like for you?

It was after the Dominican Republic - I must have been 15 – and I was sent to a Benedictine school. The brothers and priests were all Hungarian, so they came from an old world aesthetic. We had horse-riding classes, Ancient Greek, Latin. For me it was quite an eye-opening experience because I hadn’t really lived in the West. I mean, the Dominican Republic wasn't really West in that way. Let's put it this way: I'd never lived in a first world.

It was an all-boys school, a very small school, and there were two Taiwanese there and three Japanese and two from Hong Kong. No one from Mainland China at that point because of the Cultural Revolution. The Asian students all stuck together and helped each other with math and science. We all did very well in those subjects [laughs]. I'm sure we had a similar background. Terrible in PE. It's like 'What's wrong, can you throw a ball?' 'No, but I can do calculus' [laughs].

So at what point did you shift from biology to art?

That was right after college, and my father – being a doctor – thought that as the first son [Mingwei has two older sisters and a younger brother, so he’s the eldest son], ‘Why not be a doctor and take over my clinic?’

I’d studied four years of biology and at the end, I showed my parents my report card. ‘It's not because I'm not doing well, it's just because I don't have the affiliation or passion for biology.’ Especially when I saw blood. I fainted. Twice.

So my parents said, ‘Well, what would you like to do? And I said: [laughs] I was going to say art, but I blurted out 'Art….chitecture." Just thinking that they would accept it because it's between art AND science

So my parents said, ‘Well, what would you like to do? And I said: [laughs] I was going to say art, but I blurted out 'Art….chitecture." Just thinking that they would accept it because it's between art AND science. And they did. So I studied architecture, which was helpful because – as you saw – many of these installations have architectonic elements to it. So I studied four years of architecture and textiles, and after I graduated I worked in a textile firm for two years before going to graduate school in sculpture.

My parents have been extremely accepting. For most Chinese, it's like, ‘What? You want to be an artist?’ Especially for a boy. It's really not something cool. But my parents have been very open, and without their spiritual, emotional and financial support, I could have never done all these projects which are what I think of as commercially unfriendly, because they're not paintings or things people can purchase. It’s about ideas. I see it more as a philosophy, or maybe a vocation, rather than a profession.

And how would you describe your philosophy?

If I have one, I think it's about having fun. Maybe fun is not - it is the word, but it could be misunderstood as something superficial. For me, it's about looking into a deeper meaning of what it means to be us, a human being, and what it is to be living in harmony with our surroundings, including people, plants and animals.

I was talking to a curator a few years ago, and I said, 'Oh, compared to other artists, I'm lazy because I only produce two works a year.' And she said. 'No, I always see you as an artist who loves what he does, and never sees it as work.’ And I thought what she said was very enlightening for me.

And if you're not making work that's subject to the same commercial imperative, there’s not that side of the pressure.

Yes. Exactly. I'm a headache to my gallery. ‘Mingwei, we need something to sell.’

Interestingly enough, quite a few of my works have been acquired by institutions and private foundations, so I'm very lucky to be doing work in a time where people are open to these possibilities. If I was doing this ten years ago, I don't think I'd be making a living.

Why do you think that possibility exists now?

I think there are several big name artists - like Marina Abramovic and Tino Sehgal – who are doing – not my type of work, but similar. We could all be lumped as performance art. They’re well-known enough now that museums have started acquiring their work, and once they started doing that…

I wonder if there’s something, too, about this particular moment we’re occupying. Now – more than ever before – it’s technically so easy to connect with other people, to meet strangers, to make friends, to have intimate encounters, but of course that’s not always the case. I feel like we have a heightened awareness of this possibility, and of all the moments we’re not experiencing it.

Exactly. And often with exhibitional artists, it's about number, like 'How many people can experience this work? The more the better.’ But in many ways my work goes against that grain, like The Sleeping Project. There are only eight participants - only eight people who can really experience that work, and not through monetary means.

So it's probably similar to people's attention to the slow movement – things that we've lost – but I haven’t been too conscious of that until recently.

There's a gentle politics in your work, in the emphasis it places on fostering kindness.

Especially between strangers, which is quite difficult these days. The interesting thing for me is that once you open that possibility, it becomes really easy for people to do it.

Lee Mingwei and His Relations

is at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

5 November 2016 – 19 March 2017

More info here

Mingwei will be speaking about his recent work

at Auckland Art Gallery in the exhibition space

Sunday 12 February – 10.30am