So, You Want to be the “Largest Polynesian City in the World”?

We’re not your interesting cousins you get to pull out when you need an edge.

We’re not your interesting cousins you get to pull out when you need an edge.

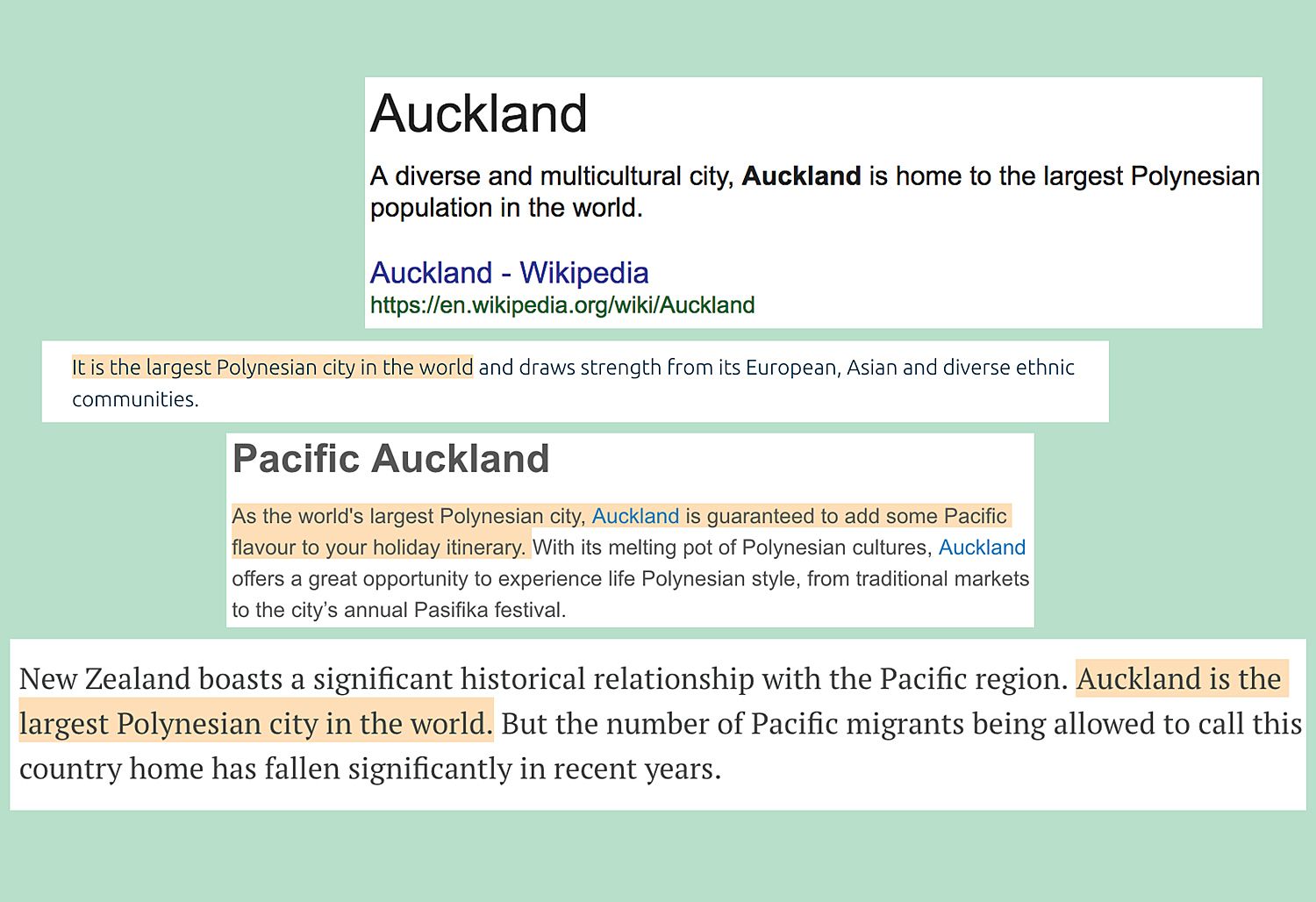

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland is the “largest Polynesian city in the world”. Or so you would believe. This phrase is a classic; pulled out in news headlines, tourist brochures and many casual conversations, especially in these weeks after Pasifika and Polyfest. Tāmaki Makaurau of course does have a large Polynesian population, and I’m included in that number. Our Polynesian populations are innovative, resilient shape-shifters who are 100% worth celebrating (all the time, not just in March, might I add). Yet there is something more sinister at play with the repetition of this diversity tag-line. One-liners like these start to act as myths, which we repeat "over and over again without knowing why". They become like "superstitions or catechisms", which are carried on for so long that they become ways in which we identify ourselves – whether or not we see ourselves as personally or geographically Polynesian.

They become like superstitions or catechisms, which are carried on for so long that they become ways in which we identify ourselves – whether or not we see ourselves as personally or geographically Polynesian

But for starters, is there any truth to the storyline; secondly, where did it originate; and third, whose agenda does it even push?

*

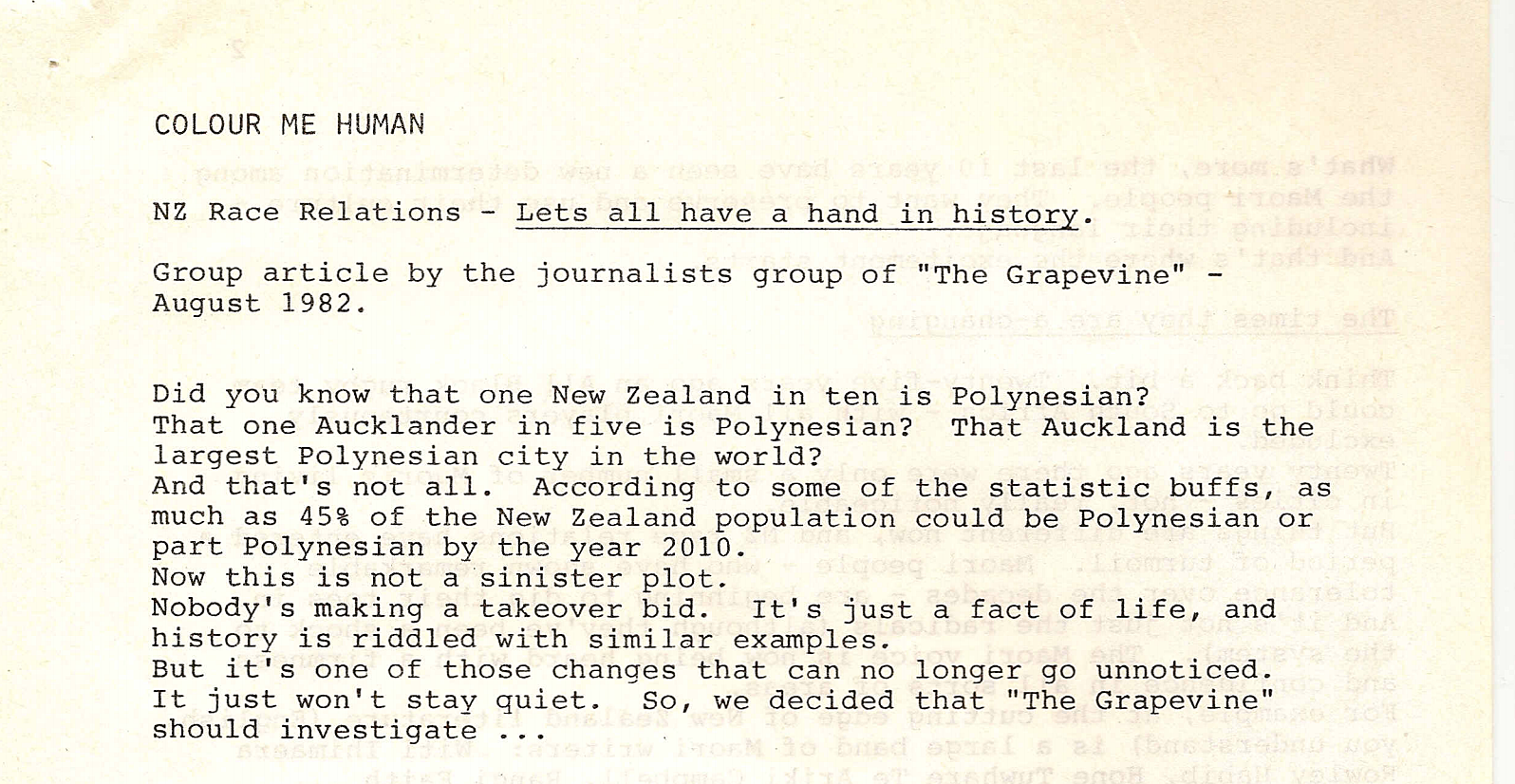

Auckland was first identified as the “largest Polynesian city” in 1966, in an article called Auckland, New Zealand's Largest Urban Area written by J. S. Whitelaw and G. T. Bloomfield. The authors were writing from a planning perspective – and a Pākehā one at that – based on the results of Aotearoa New Zealand’s 1966 census.

“Since the War an extensive migration of Maoris from rural areas to Auckland has been taking place; initially the Maoris (33,926 in 1966) tended to gravitate to the inner city area but now a high proportion live in the peripheral suburbs. Their place in the central city has been taken by Samoans, Cook Islanders and other Pacific migrants (16,057 in 1966) making Auckland the largest ‘Polynesian’ city in the Pacific.”

In this article Whitelaw and Bloomfield were homogenising Māori, “Samoans, Cook Islanders and other Pacific migrants” within the term Polynesian. In the same vein, Sir Guy Powles used the term the “largest Polynesian city,” inclusive of Māori and Pacific migrants alike, in his address to the 20th Conference of the Maori Women's Welfare League at Auckland, in July 1972.

“In recent years the growth in the urban Maori population has exceeded the overall growth figure – this means that the rural Maori population is decreasing. What we have witnessed in our life-time is what has been described as the greatest Polynesian migration in history – because of the numbers involved – the movement from the country to the town. One consequence of this is that the great city of Auckland, in which we are, is proud to call itself the largest Polynesian city in the world.”

Again, this grouping of Māori and Pacific peoples as Polynesian was used by a group of journalists called The Grapevine in an article titled Colour Me Human in 1982, which was reproduced by the Department of Education and is accessible online here. In this article, and in fact all of the earlier examples, the term Polynesian is used to highlight demographic change in Aotearoa New Zealand’s population.

The definition of Polynesian in these three examples is markedly different to its contemporary use, which in my interpretation excludes Mana Whenua from the Tāmaki Makaurau region. The exclusion of Māori from the “largest Polynesian city” line means that the phrase has become interchangeable with the term Pacific, becoming completely detached from its original use and inception (although it is important to note that Polynesian in and of itself is a problematic term and colonial way of dividing the Pacific Ocean, but we’ll save that for another time). This is clear in contemporary uses, which contextually align with the promotion of events such as Polyfest and Pasifika, Pacific migrant exceptionalism (like the claiming of Joseph Parker despite the lack of financial investment in his campaign), and boast of Tāmaki Makaurau’s Pacific communities in the promotion of our city’s tourism – all while using the line “largest Polynesian city.”

A few issues arise in the separation of Māori and Pacific migrants in these contemporary uses of the term. One being that it makes the claim factually incorrect, as Damon Salesa notes in this slide from his 2013 presentation Rethinking Pacific Auckland.

Another issue that arises in the separation of Māori and Pacific migrants is that it denies the strength of the relationship between Tangata Whenua and Pacific peoples that comes from a shared Indigeneity to Te Moananui a Kiwa. This is not the same effort to flatten Brown bodies as with the original conception of the term, but rather an acknowledgement of the strength that comes with Pacific people acknowledging their responsibilities as tauiwi, and Māori and Pacific communities subsequently working together. After all, when the relationship of Pacific migrants to Māori is mediated by Pākehā culture, let’s not forget who that really serves.

After all, when the relationship of Pacific migrants to Māori is mediated by Pākehā culture, let’s not forget who that really serves

Another, perhaps even more damaging, issue is the way that boasting Auckland’s status as the “largest Polynesian city,” actually implies that the Polynesian parts of our city are looked after and maintained. We know damn well that it’s the complete opposite. In Auckland University Associate Professor Toeolesulusulu Damon Salesa’s latest book Island Time: New Zealand’s Pacific Futures, Salesa argues that “Auckland is not a Pacific city as much as it is a city that contains another, Pacific, city. Most Aucklanders, especially most Pākehā Aucklanders, simply live as neighbours, and typically distant neighbours, to Pacific people and their Pacific city. Auckland is better understood as a mosaic, a mosaic comprised of often highly segregated or concentrated neighbourhoods, of ethnoburbs and suburbs. These neighbourhoods, if they are Pacific neighbourhoods, are highly likely to experience ‘extreme concentration’ and deprivation.”

Furthermore he argues that the “mixed isotopes of poverty, inequality and ethnicity” that make up Tāmaki Makaurau are difficult to prise apart, yet are very conveniently kept apart narratively, especially in respects to being the “largest Polynesian city”. The text further urges us to move away from the “comforting narrative” of being a ‘superdiverse’ city as “it is both a blunt and blinkered analysis, and seems curiously distant from the actual lived experience of people: it is important to remember that diversity is ‘not innocent miscellany.’”

This vision of Tāmaki Makaurau as the “largest Polynesian city” in the world features heavily in the diversity narrative of our public policy, not to mention how heavily it is littered through current and historic Auckland Council strategic documents and plans, which state that “Our ethnic groups make valuable contributions to life in Auckland. Pacific peoples, for example, are prominent in high-profile sectors such as sports and the arts, and they provide economic and trading links to the Pacific Island nations. Our status as the world’s largest Polynesian city is a key aspect of our identity.” As a region and a nation, we are quick to prop up the diversity of our population as something that gives us an edge, an upper hand, an example of how we’re doing good. This has been a point of interrogation in the work of Salesa, who stated that “In New Zealand, diversity has become what it has in the States. It’s a public policy and consumable item. So nowadays the really affluent schools want some diversity because they need to sell that to the people who are actually fee-paying. Because those parents realise that if they send their kids to all-white schools, they will actually be missing out on something. So those parents, just like at Harvard and Yale, are in favour of a manageable level of safe diversity. And a lot of that has transferred into public policy.”

As a region and a nation, we are quick to prop up the diversity of our population as something that gives us an edge, an upper hand, an example of how we’re doing good

Holding on so tightly to Auckland’s branding as the “largest Polynesian city” when Polynesian peoples (and their marginalised living conditions) are of so little concern serves other strategic means. With the phrase’s ambiguity, the city is constructed as being geographically Polynesian, giving it some stake in – and power over – the region and its neighbours. This is no different to how America constructed the term Asia-Pacific, in which they included themselves in order to justify some geopolitical interference with Asia. And for Pākehā who claim Pacific Island identity because New Zealand is a Pacific Island, give me a break, and I don’t care if your Polynesian friend sanctioned it.

This geographic claim to Polynesia, disguised as being celebratory in nature, takes advantage of the Pacific’s easy-going nature – placing us as the fun side-thing. This simplifies the Pacific’s long and entangled history with Aotearoa New Zealand, abdicating our country’s responsibilities to the region in the eyes of Middle New Zealand. This was evidenced in the insipid ‘commentary’ spouted by Mike Hosking in response to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s trip to the Pacific, which was titled What return does New Zealand get for splashing the cash in the Pacific. In reality, Pacific migrants in New Zealand have played a major role within the country’s economy. This includes an export market valued at over $1.3 million annually, a tourism market bringing in nearly 100,000 people annually, 11,100 low-paid labourers working in our orchards through the RSE Scheme and who fish to bolster New Zealand Fisheries, which alone is estimated to be worth around US$6.4 billion a year. On top of this we do the jobs that you don’t want to do, that you don’t want to see, as the labour force that keeps this city going. And note, I haven’t even touched on the All Blacks (or Silver Ferns or Warriors or Black Ferns or other professional athletes and Olympians), artists, actors, theatre makers or politicians yet.

This storyline of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland as the heartland of Polynesian experience does not come from us, but rather co-opts us and our value, painting an alternate reality of the city

This storyline of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland as the heartland of Polynesian experience does not come from us, but rather co-opts us and our value, painting an alternate reality of the city. Ultimately this serves a purpose that does not benefit Polynesian people, because for many of us who call Auckland home, we are still excluded from parts of the city that are hostile toward us. This glossing over of Pacific realities is easy to do in a city that is so segregated. One can celebrate the fictional Pasifika festival version of us, while at the same time never having to confront Pacific marginalisation.

So Auckland wants to be the “largest Polynesian city” in the world? Great! But let’s recognise that for that storyline to even be true it has include Māori, as it did when the phrase was originally coined. Furthermore, let’s move beyond the Pacific community being whipped out as a nod to the interesting cousin on the side, and rather acknowledge the long and integral role of Pacific people here in Aotearoa New Zealand.

*

Postscript: My world oscillates between many Pacific cities. Every morning I leave Ranui, a West Auckland Pacific city very similar to the one down the road that formed me, Henderson.

I drop my kids in their Pacific city: their bilingual Samoan preschool in the heart of Ponsonby. Here English is not to be spoken and the smells of Samoan food linger at 8am. The locked gates around their a’oga amata protect them.

Having just dropped them off, I write this final draft from Lei, a Tongan-owned café on Williamson Ave. Then this afternoon we will return to Ranui to start the process again.

Pacific people in Aukilani – us homeowners, postgraduate-educated, ‘successful’ ones included, not just the ones that fit the ‘deficiency’ stereotype – are running between buoys. The buoys are Pacific spaces that can be seen as evidence of Auckland being “the largest Polynesian city” – Pacific-owned businesses and bilingual schools – and yet, they are floatation devices, offering brief reprieves from the environments that are so obviously hostile. My Auckland, the only city I really know, isn’t a Polynesian city; it’s a Palagi one, with Islanders living in it.