Landmarks and Features: Henrietta Harris

We chat to New Zealand artist Henrietta Harris about The Hum, murder mysteries, and how she makes a living.

I

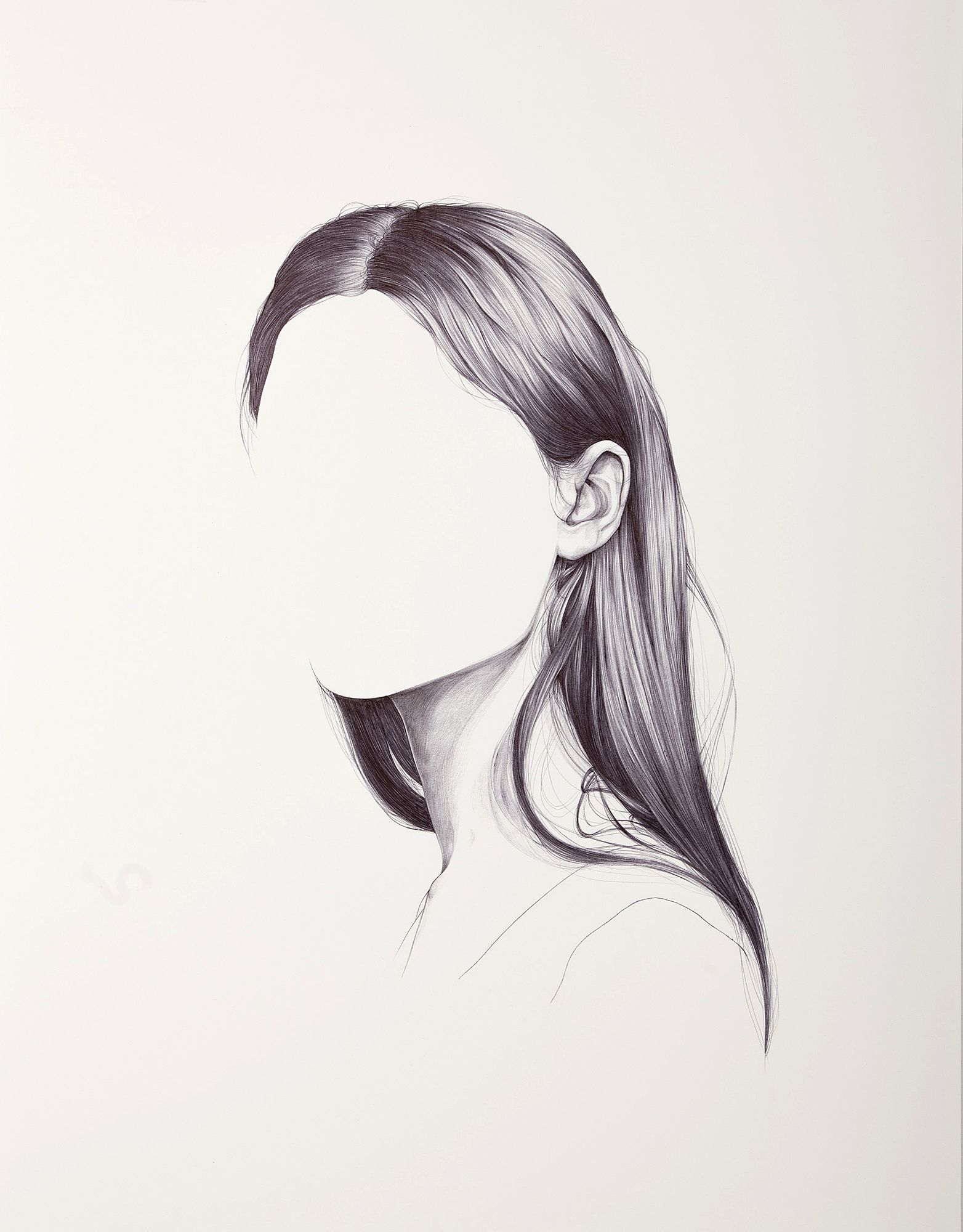

Like her portraiture, Henrietta Harris is at once entirely present and perplexingly hard to read. Sitting in a dimly-lit café, she speaks with careful composure, eyes widening with shy disappointment whenever the conversation turns personal. In the same way her drawings direct your gaze to the typically overlooked – a swerving jawline, a kinked eyelash – so, too, does spending time with the artist.

Her biggest show yet, The Hum, opened at the Robert Fontaine Gallery in Miami last week. It’s been a year in the making, the longest she’s spent on a series of works. “I’ve just been doing these huge paintings, for months, and each takes about a week, which is ages for me.”

Some of the pieces are impressively large. Spanning whole-body heights, they threaten to engulf you in their unsettling illegibility. “She’s done something that I don’t even know I can fully explain,” her gallerist Robert Fontaine tells me over the phone. “Artists have a responsibility to their generation to paint from their own time, their own moment in history,” he says. “Henrietta’s work is challenging because it’s painted with watercolour, yet she manages to calculate these interesting forms with a precision that watercolour doesn’t always allow.”

Her paintings also capture a truth rarely acknowledged in portraiture: that our sense of self – particularly when we’re young, which her subjects always are – is slippery, fluid, not yet fully formed. “I like people to look a bit vulnerable or unsure, or to be quite alone,” she says. “Eyes closed, or gazing at the ground. I’m drawn to that.”

II

She spent her childhood on a vineyard in Kumeu. Her father made wine and she spent her afternoons drawing. “I was very anxious and neurotic,” she says. She tilts her head, pauses. Adds, “but probably not as much as I thought.”

III

The past year – the one she spent working on The Hum – has been her hardest one yet. “My dad has Alzheimers,” she mentions hesitatingly. “Dealing with him is so surreal. He’ll have conversations with himself and you’ll feel like you’re losing your mind.”

She circles around this experience in the show, hinting but never stating this fact. Each of her titles revolve around memory and disjointedness; ‘the hum’ refers to the widely-reported but rarely-verified phenomena of low-frequency droning, audible only to a handful of the population. It’s not unlike a car idling patiently in the distance: always waiting, never moving, just audible enough to drive you mad.

Because she never got her licence, she never strayed far from home when she was growing up. This holds true even now: asked if she’d ever leave New Zealand, she shakes her head. She intends to continue exhibiting overseas, but Auckland is where her family is.

IV

A couple of years ago, she decided she wanted to be a fine artist rather than a commercial one. “I wanted to take it seriously.” She wanted to be in galleries, not magazines, so she started turning down advertising jobs to work on The Hum.

That swing led to a change in how she approached her art. “I used to have this weird thing where if something I was doing got too popular, I’d be like: Okay, that’s over. I’ve got to do something new – almost willing people not to understand me. But working on this show, I’ve had to think: hang on, this is actually my job, and I need to create a financial future for myself. So I’ve stopped being so stubborn. I’ve realised I should actually listen to what people are saying.”

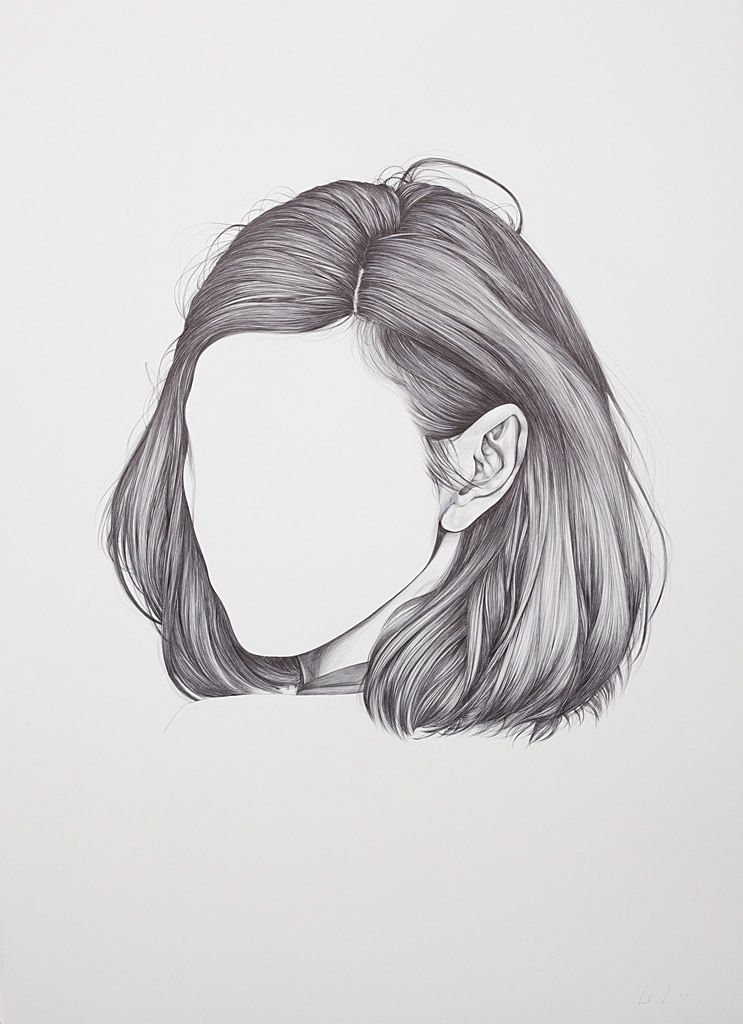

She really does listen. When specific drawings receive enough attention on her Instagram, she’s more likely to continue making that kind of work. Of course, it’s not always easy to predict, and she doesn’t always follow their lead. Sometimes she’ll spend a week on a painting, but it’ll be ignored in favour of a quick sketch. “The pen drawings are popular because the tools are so accessible,” she comments. Most people will have used a ballpoint pen in their life, so they appreciate what she can do, whereas watercolours are more mysterious and harder to understand.

Her career has reached a peak in the past year: last November she exhibited at Art Basel and after this solo exhibition she’ll be part of a forthcoming show in Tokyo. Jonah Hill wants to buy her work, Sam Smith wants to collaborate. Here in New Zealand, she was a finalist in last year’s National Contemporary Art Awards, but she ended up losing to a tube of plaster. “I felt so out of place there,” she remarks. “I felt like I was the token technically-quite-good-so-we’ll-put-it-in.”

The paradox of Henrietta’s practice is that in any other industry, she might be accused of selling out. But in the contemporary art world, her mainstream popularity practically consigns her to a niche. She feels like her work isn’t conceptual enough to be accepted. She gets seen as an illustrator, but not an artist. “It’s silly and naïve of people to categorise her as that,” says Fontaine. “We forget that Andy Warhol was doing windows and Salvador Dali had been doing china plates and Picasso was doing wallpaper designs at the beginning of their careers.”

Henrietta’s own collaborations extend into fashion and music: she’s painted for labels like Liam and for record companies like Flying Nun. Two Easters ago, she painted an ostrich egg for the Department Store, imposing on its smooth head a kind of angry topography. Karen Walker bought it, and six months later Henrietta received a letter saying it had inspired their resort collection. There was also some money enclosed. “I was quite chuffed,” she says.

It’s unique to hear an artist speak so frankly about the commercial elements of their work: so often it’s treated as a subject that taints their integrity, rather than a pressing, fundamental reality. After all, the artist really does have to live like everybody else. As for how she’ll continue making that living, she’s not sure what she’ll work on next. She’s contemplating oils, she’s considering bigger canvases, but ultimately, she’s not sure. “Everything I’ve done over the past year has been leading to this. If it sells well, then I might keep doing it. Because it’s just work, you know? It’s just a job.”

V

Though she hasn’t done many interviews, Harris gets asked a lot of questions online. There are two she especially hates, and she fields them with increasing regularity: what pen she uses, and where she gets her ideas. “The question should be how many years I’ve spent teaching myself to draw.”

The answer to that is more than a decade. “I just kinda work till I’m absolutely burnt out.” You can see that dedication in the evolution of her style, but she feels it in her body, in stiff joints and sore arms. For a while she was worried she’d have to stop drawing for good. “My wrist is so weak now,” she explains. “And this –“ she extends her right arm, “I can’t straighten it fully anymore.”

In the same way she’s reframed her practice as a commercial enterprise, stripping away much of the romanticism, she’s also changed her routine: she exercises, sees a physiotherapist, and sticks to office-job hours rather than toiling late into the night. Every morning, she walks into the CBD, up the four flights of stairs to her studio, and puts on a murder mystery audiobook. The chapters bookend her day. Recently she tried some Ian McEwan, but suspects it’s just a phase. “All the books have a twist at the end, and they’re all horrible.” There are exceptions. She liked Sweet Tooth. “But I think my audio file was incomplete.” She blinks. “I think I missed the twist at the end.”