Power of the Story: A Review of Kurangaituku

Whiti Hereaka’s new novel, Kurangaituku, takes the pūrākau of Hatupatu and the Bird Woman apart like an old dogskin cloak, cutting it into patterns and shapes never seen before. Ariana Tikao reviews.

The matakite is standing opposite, pleading with me to cut off her hands. I refuse. She is getting more insistent, and now she is yelling at me in desperation. If I cut off her hands, she can transform into the bird woman, Kurangaituku. I complete the gruesome task and am sucked into what I recognise as the contemporary world. A hearing of sorts is taking place. I’m being questioned by two men speaking in Māori. They are trying to ascertain whether what I have done is tika or not. That dream still haunts me...

I remembered it a few years back while developing Wāhine: Beyond the Dusky Maiden,an exhibition about Māori women. Working as a Māori specialist at the Alexander Turnbull Library, with my co-curator I was selecting wāhine to profile, and as a child I had been intrigued by the story of Hatupatu and the Bird Woman. After this dream, I felt that Kurangaituku wanted to be represented, so I called my friend Aroha Yates-Smith for guidance. Aroha wrote a hugely significant PhD thesis on rediscovering the feminine in Māori spirituality. ‘Hine! e Hine!’, written in 1998, is about the importance of atua wāhine, our goddesses. Like so many wāhine in our pūrākau, the story of Kurangaituku had been corrupted, but through Wāhine: Beyond the Dusky Maiden, my colleague and I had a chance to let her story be viewed through another lens.

In the same folder was an accompanying note and translation by Hone Tūwhare, who worked for the library in the 1980s as a Māori specialist

I found a version of the kōrero in a manuscript in te reo Māori by an unknown writer in the library’s collections. In the same folder was an accompanying note and translation by Hone Tūwhare, who worked for the library in the 1980s as a Māori specialist. His note says that Kurangaituku went to the coast to gather kaimoana, and while she was gone, her captive Hatupatu killed and ate one of her kererū and then slaughtered her other pets.

When espying the dirty traitorous work that Hatupatu was doing the riroriro immediately flew off to find the old lady and tell her of Hatupatu’s misdeeds. When the old lady arrived Hatupatu had left. The old lady had a keen [sense of] smell and after sniffing in all directions discerned the path Hatupatu had taken. The chase began. – Hone Tūwhare

Tūwhare says that Hatupatu recites a charm, ‘Matati Matata’, to open up a crevice in a tree, which he hides in. He uses the same ‘password’ later to hide in a rock. When he emerges from the rock, he continues his escape and leaps over some boiling thermal water, but Kurangaituku falls into the pool. It is there that she dies.

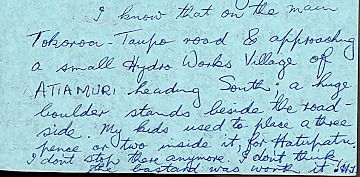

A note written by Hone Tūwhare in MS-Papers-2686 [detail], Alexander Turnbull Library

Tūwhare reveals he used to stop off at this rock, where his children would leave coins to Hatupatu. He finishes by saying, “I don’t stop there anymore. I don’t think the bastard was worth it! HT.”

Tūwhare also reveals that he used to stop off at this rock, on the side of the Tokoroa–Taupō Road, where his children would leave coins as an offering to Hatupatu. He finishes by saying, “I don’t stop there anymore. I don’t think the bastard was worth it! HT.” I couldn’t believe my luck in finding this little gem in the collection, and included it in the exhibition to demonstrate how Kurangaituku had been maligned, to provide some balance to the story. Over 200 years from when colonisation first began in this country, it feels opportune now to re-examine the stories we have been told. To understand the history and motivations behind the ways our kōrero, as wāhine Māori, have been shaped by others.

Whiti Hereaka’s new novel, Kurangaituku, published in 2021 by Huia, takes the pūrākau apart like an old dogskin cloak. Cuts it into patterns and shapes never seen before, weaves it into new narratives twisted in with old threads of kōrero.

[Hatupatu] told himself it was just a story, as if a story was something frivolous. But he knew the power of story. He had used it to shape reality…

This novel is multi-dimensional, and I feel that Kurangaituku may have pleaded with Hereaka (like the woman in my dream) for her story to be (re)told. Although Kurangaituku does not have her own audible voice in the book, she has been given an atamira, a platform.

A bird who cannot sing. A ridiculous creature.

It is sad indeed to be a creature who is unable to sing its own song. I have never had a voice of my own – I use the thoughts of others to communicate. I clothe myself in their accent, cadence and language.

There is a deep mamae in the narration, which has a certain resonance today. When I think of the above quote, it reminds me I am writing in this language of the coloniser. Although I have spent many years learning te reo Māori, it will never be my mother tongue. For most of us, it is necessary to communicate in English, the language we were first surrounded by, that shaped our being.

Kurangaituku uses the power of her mind to communicate with birds. In turn, they mould her with their own understanding of the world. In order to speak with Hatupatu, as he is human, Kurangaituku steals a pet tūī who has been trained to talk. The tūī can only speak a simplified version of her thoughts, growling when she tries to squeeze an idea into its mind that is too complex. For many of us second-language learners of te reo Māori, it is like that when we are trying to express ourselves fully in the reo of our tīpuna. I’ve felt that growl of resistance inside myself.

Although Kurangaituku does not have her own audible voice in the book, she has been given an atamira, a platform

Hereaka’s theatre background is evident when Kurangaituku breaks through the fourth wall, addressing the reader directly. Kurangaituku bemoans her unlovability:

I am a liar, a thief, a murderer. I killed the birds of my flock for a hunger that was more than physical. I would suck the sweet brains from their skulls and see their life experience … The book in your hands is bloodless, yet is it not the same thing? You sup on the experiences of others – how many lives have you tasted? … A story lets you glimpse the world of the other – past, present, and future – a life just waiting to be savoured.

The book is not an easy read. There’s a sex/rape sequence that could possibly do with a trigger warning. However, the violence of that scene is balanced out later on with a much more empowering sex scene between Kurangaituku and Hinenuitepō.

I feel some of the ideas around female genitalia are more aligned to a Western perspective, which doesn’t sit right in a story set in pre-European times. For example, the words ‘hanga kino’ and ‘whare haunga’ are used to describe Kurangaituku’s genitals, and translated in the book as ‘evil thing’ and ‘stinking house’. It is my understanding that wāhine were revered for their whare tangata, their power to house future generations in their wombs. Perhaps that sense of disgust and shame relates more to Kurangaituku not being fully human, and it is Hatupatu’s own whakamā at wishing to mate with her that is being projected onto Kurangaituku with that negative imagery? Kurangaituku also uses the anachronistic phrase “It is what it is” – a common cliché of our times.

The structure is much like Māori oratory – not linear, but existing in different times, cycles, and spaces all at once, then looping back on itself

Despite the above, Hereaka and her publisher have produced a unique novel that is one to experience. When I first picked it up, I wondered which end to start from. The two covers mirror each other like those upside-down dolls from childhood. Set in supernatural realms, the timeline is measured in aeons, not years or centuries. The structure is much like Māori oratory – not linear, but existing in different times, cycles, and spaces all at once, then looping back on itself. This challenges us to see stories as more complex, to read in different ways, and from multiple viewpoints and directions.

The song before the light is almost a prayer, an entreaty for the light to return.

Darkness must inevitably arc into light. Ki te whaiao, ki te ao mārama

It’s a daily miracle, and the birds’ song is partly joy that the light has returned, andpartly joy that they are alive to witness it.

Kurangaituku is published by Huia Publishers.