Is This Conversation Over-Cooked?

Reflections on HERE: Kupe to Cook at Pātaka Art + Museum

Migoto Eria reflects on HERE: Kupe to Cook at Pātaka Art + Museum, asking if it hits the mark biculturally, inclusively and with autonomy.

Tūi, tūi, tui, tuiaTūia i runga, tūia i raro

Tūia i roto, tūia i waho

Tūia te here tangata, ka rongo te pō, ka rongo te ao

Tūia te muka tangata,

I takea mai i Hawaiki nui, Hawaiki roa, i Hawaiki pāmamao

Te hono i wairua ki te whai ao, ki te ao marama

Tīhei Mauriora

The sewing of thread, and the binding together of two pieces of fabric. The needle of ancient thread goes up and down, in and out. The bringing together of the two pieces, being that of people and that of origin, of that distant place called Hawaiki. And once the two pieces become one, light comes forth. We celebrate life.1

It was rather exciting to be able to experience Pātaka’s interpretation of Cook’s encounter with Aotearoa, as 2019 is the 250th year since the arrival of the Endeavour. What I was looking forward to before visiting the exhibition is the unravelling of a complex and challenging conversation, and how I was going to apply my litmus test: is it going to hit the mark biculturally, inclusively, but more so with autonomy?

What I look for are words such as: biculturalism, Māori and Pākehā, colonisation, tangata whenua.

This year I’ve experienced many renditions of how people have responded to the 250th year since Cook’s voyage. This has created, in my mind, a platform of what to expect and an almost predictable narrative, mainly containing the words/names: Dual heritage, encounters, voyaging, Cook, Banks, Endeavour, native specimens, Tupaia. What I look for are words such as: biculturalism, Māori and Pākehā, colonisation, tangata whenua.

And more importantly, who’s talking about us – and are they Māori or Pākehā?

So I ponder here on the conversation of biculturalism in Aotearoa, and how well this exhibition has achieved this.

Entering the exhibition, we plunge into the depths of blue, to Tangaroa and to Te Moananui-a-Kiwa. It’s refreshing that there is an added element to this supposed bicultural conversation, and that is that our cousins from the Pacific are also integral to this whole process. Cousins is an understatement, they are our tuakana (the elder sibling of our Pacific Family).

The word HERE is the first dialogue you experience on walking into the exhibition. Depending on your perspective, you are going to think of either the locative and being present, or the Māori interpretation, meaning to bind, to tie up. This has to do with the binding of lashings or mooring a vessel on the water. Both perspectives are valid and suitable for this kaupapa and make for a very simple but effective start to a discussion of voyaging, travelling through time and across the sea.

What was clearly the centrepiece of the entrance was a large round stone with a hole in the middle, its smooth surface indicative of the many hands that have touched and admired it. This stone is called a punga, an anchor stone, with the name Maungaroa. The notion of anchoring to a place, or being fixed to a place after travelling a long way, is achieved here. The stone itself is said to be one brought by Kupe from Rarotonga, according to archaeological research, and was renamed after it arrived here to Te Huka-a-Tai.

A famous Kiwi icon, our yellow street signs with black uppercase type, made by the Automobile Association, or AA. I’m using the words Kiwi and icon in an attempt to avoid the word kiwiana and then visuals of pavlova and gumboots… this way-finding installation is very interesting. Firstly we recognise it as a Kiwi icon. Secondly, the place names on it aren’t places you’d find in Aotearoa. Thirdly, the whole post itself is on the ground as if someone had slowly reversed their car into it. And then I thought, aren’t we in the sea? This installation is by Margaret Aull, called Seek Utopia, The Way Home series, 2013.

Challenging the narrative of ‘lost at sea’, Greg Semu recreates the ‘accidental’ arrival in his work The Arrival, 2016. His depiction shows a theatrical representation of the characters, as well as the intentional temporary backdrop of blue tarpaulin and clear plastic instead of the tumultuous waves of the sea. The image is almost convincing enough to be a print of the original painting until close inspection gives you a better understanding of what’s actually going on: it’s not true, it wasn’t an accident, nor were the several other arrivals!

I see a silhouette of a woman wearing Victorian dress staring out to the ocean. I’m seeing shades of The Piano, when the mother and daughter arrive at the beach to unpack their crated piano that has come off a ship. This is the 19th century, settlers arrive on the coastline of Aotearoa with their long dresses dragging on the sand and, of course, rescuing their pianos. As you walk past this work, the image’s movement catches the eye. I was already familiar with the work of Yuki Kihara, who had exhibited in Napier at MTG Hawke’s Bay. In her work Takitimu Landing Site, Waimārama, 2017, Kihara references the fact that Māori and Rarotongan histories speak of the creation of an ancestral waka that was made in Sāmoa. Takitimu, known as Te Waka Tapu o Takitimu, was the vessel that carried priests, or tohunga, so is remembered as the waka that carried higher knowledge, or wānanga. I can’t help but feel that the woman has been orphaned of something important and, as her dress suggests, is in mourning. Perhaps mourning for family or that this is what has become of the landing site of the great Takitimu waka: desolate, isolated and lonely.

And while we’re in the water, the work I AM WAI (2012) by Israel Tangaroa Birch is a wonderful play on the word WAI and the words I AM. As the narrative suggests in this section of the exhibition, wai is a huge part of the navigator’s experience, but it is more than that. If you turn the word WAI on its head it becomes I AM. This is that conversation about the care of the mauri of our water in Aotearoa, and that it isn’t a Māori thing, it’s about sustenance and life. As Bruce Lee suggests: “Be water, my friend.” Wai is part of us, and part of our whakapapa. If we become one with water, then, water is our past and our future.

What I’m finding quite difficult is trying not to indulge too much in each of the artworks or to place bias on some and not others, as I too am one of the ships lost at sea in the first section of the exhibition (with no directions), and perhaps this is intentional, I needed a life buoy...

Floating and bobbing into the next section, I see it features a work by Kazu Nakagawa. What is striking to me in this work is the idea that we are one people by the sea, and by the sea we transgress time, knowledge and history. It’s almost as if we communicate by sea, as it is what we understand most, and in a mutual sense. As Nakagawa suggests, the space between the Japanese and the Pacific peoples is called ‘Ma’ or is known as the space between two structures. This also acknowledges the migration of people to Aotearoa who know the ‘Ma’ only too well, the space between home and Aotearoa.

We experience Tupaia’s ordeal through the pilgrimage to Tahiti, in the video Tupaia’s Endeavour, where to this day, the ordeal that Tupaia and Taiata endured is mourned, acknowledged and remembered.

Tupaia, the Tahitian guy who could speak to and be understood by Māori, the same guy who traded a crayfish in exchange for a piece of cloth. It is he who helped Cook navigate the Pacific, and also tried to bridge the gap of communication with the Māori people. Not all advice from Tupaia was respected and taken seriously by Cook, both on navigation and on first encounters of the visited sites. And to think of the moral and emotional strain on an already stressful relationship and situation, it’s no wonder Tupaia had become ill after losing his companion Taiata. It is recorded that at the death of Taiata, Tupaia was overwhelmed with grief, and a painful and relentless sob was heard at a distance for the loss of his friend. Only two days later, Tupaia himself died. We experience Tupaia’s ordeal through the pilgrimage to Tahiti, in the video Tupaia’s Endeavour, where to this day, the ordeal that Tupaia and Taiata endured is mourned, acknowledged and remembered.

Many elements of emotional and physical turmoil, their reality and impact, surface in other interpretations of this encounter. However, the realities and impacts, although interpreted through a human perspective, also affected the environmental and cultural perspectives – all peoples, environments and sites that this voyage touched. We witness the non-human impacts of this voyage through works such as Bill Hammond’s Unknown European Artist, 2004, and then the coming together of both environmental and emotional impact is captured in Megan Jenkinson’s The Florentina Pectora (Flowering Heart), 1987. Physical implications, illness and disease are explicitly articulated by blood-stained handkerchiefs and napkins, and the hanging strands of ribbon that remind me of the all-too-common notion of mourning and sadness – whilst assembled in such a way that seems from a distance to resemble a kākahu Māori, or Māori cloak. People clothed with illness, disease and sadness, all the while using a napkin to wipe their sadness, and gifting ribbon empathetically to those they visited in different places.

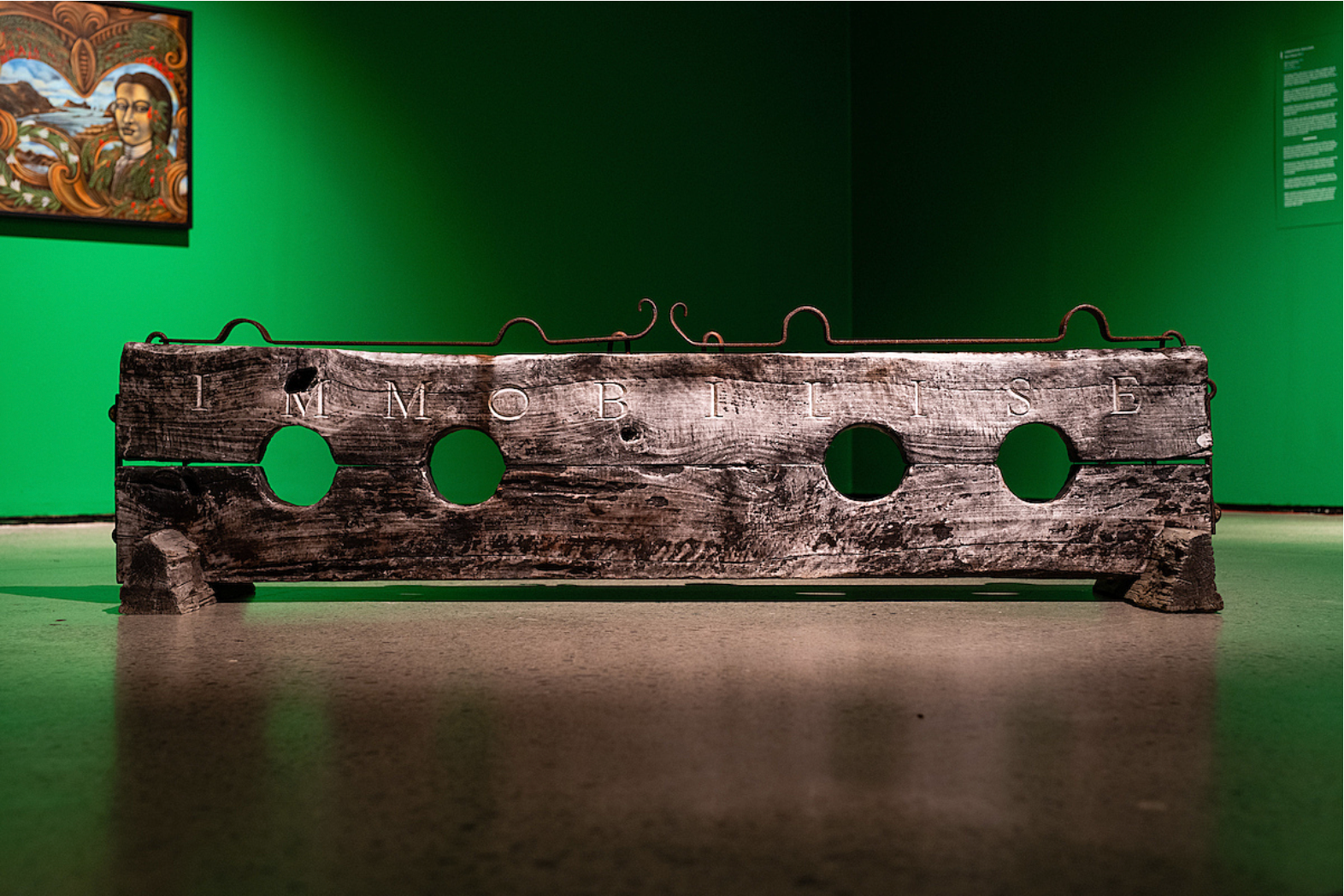

I think about the cultural lens, perspectives, and who is being documented or subjected as an item of research, but more, who is practising autonomy and is in a position of power? Who is the one etching perspectives about a culture that they are seeing through a microscope? Rangi Kipa’s Immobilize, 1999 challenges the one-sided narrative of Cook that overlooks the grim and malicious nature of the relationships he had with those he brought onboard, some without consent. Immobilize sees a person locked into a situation, in the most demeaning and demoralising way, and also speaks to Cook’s practice of abducting and ransoming high-ranking people to be part of his expedition.

One will never truly understand Cook’s full intentions and perhaps he too wasn’t sure, but he made some devastating decisions which will forever be etched into the DNA of all people, sites, times.

Is this conversation over-Cooked? The conversation being, acknowledging the 250th year since Cook’s visit, and asking if we have started to regain consciousness of the full picture: the importance of understanding and learning about all perspectives. This is only but a trailer of the mini-series; one must actually read the book and not resort to watching the movie. One will never truly understand Cook’s full intentions and perhaps he too wasn’t sure, but he made some devastating decisions which will forever be etched into the DNA of all people, sites, times. The residual energy of another time acknowledged and articulated here in this exhibition, true agents of cultural redress.

I hope that we can continue this kōrero, cooked or medium-rare, and chew on the fat a little longer. Every little bit helps.

1 This karakia was written by the Pou Tikanga of the Ringatū Church, Wirangi Pera of Te Aitanga a Mahaki.

HERE: Kupe to Cook

11 August – 24 November 2019

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Pātaka Art + Museum. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

All photographs by Mark Tantrum.