Kill the Auteur, Make Something Great

All good things must come to an end. And so should auteur theory, if cinema is to advance.

All good things must come to an end. And so should auteur theory, if cinema is to advance.

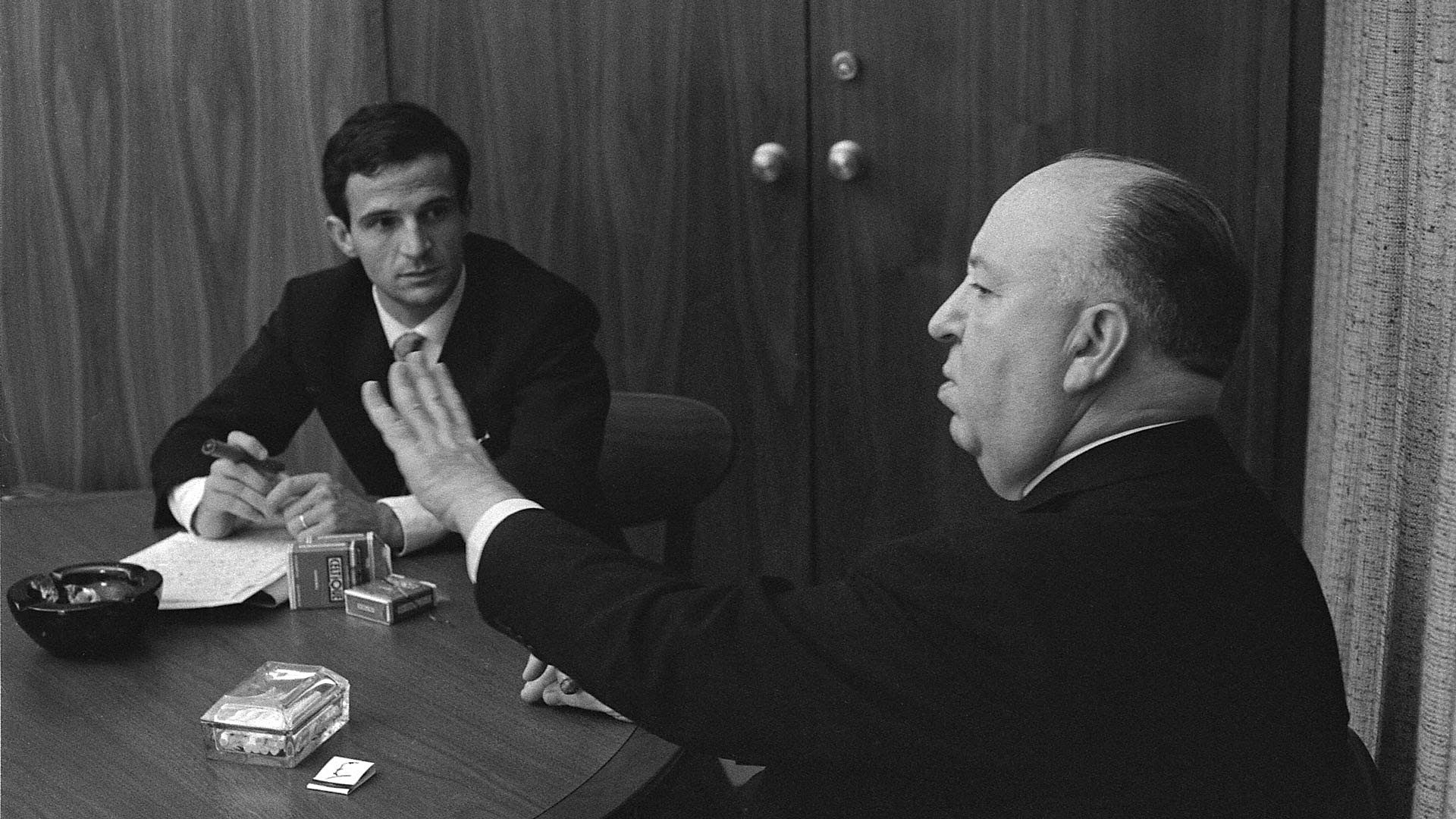

Pity the poor, tired, worn auteur theory. Conceived in France in the 1940s by the likes of André Bazin and François Truffaut as a way to assert the director, not the writer, as a principal author of a film, it has expanded to become the single most widely-accepted way for the masses to understand film production.

Films are routinely referred to in shorthand by their director’s name – the new Nolan, the latest Spielberg, classic Bigelow – as if directorhood and authorship are indistinguishable. And in those cases where the dissonance is too glaring to be ignored – be it in films strongly driven by producers, actors, or collaborative filmmakers – the theory is not put aside for more accurate authorial theories. Instead, it’s distorted to argue that, say, Marvel Studios are in fact the real auteur of Marvel movies, or that Steven Seagal is the true auteur of his movies – a distortion that ends up literally as far away from the original notion of recognising the director as possible.

I don’t hate auteur theory, even if it has largely run its course and had a necrotising effect on cinematic culture from both audience and creative perspectives

I don’t hate auteur theory, even if it has largely run its course and had a necrotising effect on cinematic culture from both audience and creative perspectives. Without it, history wouldn’t have celebrated the likes of Hitchcock, Samuel Fuller, or Howard Hawks, all of whom worked in ostensibly disreputable genres and used cinema in vivid and expressive ways that are still part of our cinematic vocabulary today. This in turn powered a range of filmmakers who expanded the notion of ‘direction as personal expression’ into the popular cinema, from Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola to John Cassavetes and Quentin Tarantino. And auteur theory still has its uses, even in 2018: see how Thor: Ragnarok differs from other Marvel films in Taika Waititi’s use of themes of Indigenous sovereignty, or how the recent strand of vulgar auteurism has justly elevated the reputation of directors like John Hyams, whose stock in trade tends towards direct-to-video Universal Soldier sequels, and yet whose camerawork and staging of action is more worthy of analysis than the average Oscar-nominated director. (I’m more sceptical about the vulgar auteurist celebration of Resident Evil director Paul W. S. Anderson, but my jury’s still out.)

But when your only tool is a hammer, everything begins to look like a nail. For every individual director who uses cinema uniquely to express their viewpoint, there are a dozen who are essentially traffic cops given ‘a film by’ credit. And for independent filmmakers, if your only choices are ‘the power of the system’ or ‘the crusading genius of the auteur’, that distorts your line of vision. You believe that you have to look like a powerful, lonely, misunderstood genius whose force of vision must come from the top down and drive every element of its creation. You believe that you have to be, say, James Cameron.

I don’t hate James Cameron, either, even if I find horrific the reports of how he runs his co-workers into the ground with long hours

I don’t hate James Cameron, either, even if I find horrific the reports of how he runs his co-workers into the ground with long hours. Cameron’s made some great films and he’ll continue to make great films, infused with his personal sensibility. Hold up Terminator 2 or Titanic (yes) against any 2017 big-budget spectacular, and the difference is night and day. The fact that his personal sensibility is less of the woozy romanticism of Godard or Wong Kar-Wai and more about “wouldn’t it be cool if a guy wearing a mecha-suit had a giant knife?”, or that his motivation for certain camera angles is most sharply driven by his love of scuba diving, doesn’t make auteur theory any less relevant in understanding his films.

Cameron is also auteur theory taken to its logical endgame. Rumour has it that on Avatar Cameron did at least one take operating each of the cameras covering a scene (he’d have minimum two cameras for most scenes, sometimes more). Steven Soderbergh once noted that he took solace in the fact that while Cameron seemed to be able to do everything, he probably still needed makeup people – until the day he saw Cameron fixing an actress’s makeup. In a collaborative medium, he’s ensured that there is no element of the operation that he does not have tangible control over.

Which is, y’know, one way to make a film.

*

Here’s another. Get nine talented people in a room. Have a theme in mind, and a loose structure for encapsulating that into a feature-length film. Develop a strategy to divide that theme into eight stories, with a formal carapace that provides a bit of unity, some consistency of production, and a lot of individual freedom. Then have those talented people go hard and make their films. Or, more accurately, their film.

I can’t shut up about Waru since seeing it at the New Zealand International Film Festival 2017. Which I feel bad about, because its principal kaupapa – to understand the question, “If it takes a village to raise a child, does it take a village to destroy one?” – is not what has principally captured my imagination. Going in, I was sceptical of its formal gambit – eight stand-alone scenes, each done in one take, each by a different filmmaker (seven writer-directors, one writer-director team).

coming out of the cinema, I was floored. One of my long-held gripes with ‘social issue filmmaking’, so to speak, is its reductive storytelling nature

However, coming out of the cinema, I was floored. One of my long-held gripes with ‘social issue filmmaking’, so to speak, is its reductive storytelling nature. Be it Ken Loach or Paul Haggis or whomever, ‘issue films’ have inevitably felt like a narrow, blinkered perspective on the complicated problems of society, which are convincing only to the extent that their narratives shutter out the rest of reality. Waru neatly slices through this Gordian knot by saying “okay, let’s bring in the rest of reality”. While ultimately the realities depicted in Waru are too far from my experience for me to assess whether something important has been missed, the inclusion of such a wide range of perspectives was fiercely invigorating, and one that would have been impossible from a single director’s perspective.

To be clear, auteur theory can be useful to a degree in understanding Waru – authorial differences in each segment can be clearly perceived, and those can be connected to other works by the creatives involved. But by approaching the film from a non-auteurist mindset, its creators have made something unique – and distinct from other omnibus films like New York, I Love You; V/H/S or 11’09”01 September 11 – something deeply collaboratively conceived. And that's where I think the inspirational genius of Waru lies. By not looking to create a film that fundamentally adheres to the auteur model, they’ve broken the game wide open for any number of non-traditional models for feature films, Kiwi or otherwise.

Waru is an extreme example, but it’s far from the only film made in a collaborative manner. From filmmaker pairs ranging from Christopher Pryor and Miriam Smith (The Ground We Won, How Far Is Heaven) to the Coen Brothers and the Wachowskis, the notion of collaboration is understood to a degree, even if these pairs have historically been forced into a single director’s credit. Even in the realm of celebrated auteurs, it is rare we find them standing alone. Thelma Schoonmaker has edited every Martin Scorsese film. Stanley Kubrick never wrote an original screenplay, often standing on the shoulders of giants, sometimes – think Arthur C. Clarke in 2001: A Space Odyssey – walking alongside them. The films of Quentin Tarantino have changed – and not for the better, at least in the short term – with the death of Sally Menke, his editor since Reservoir Dogs, in a hiking accident between Inglourious Basterds (his masterpiece) and Django Unchained (which I like, but has its sloppiness). The films of Claire Denis are, to my eyes, always stronger and more interesting when she is working with DOP Agnès Godard.

For a long time, my major problem with the fetishisation of auteur theory was that it wiped out the collaborative contributions of all these people whose collective intelligence makes a film so much better than any individual can on their own. (I haven’t even begun to talk about actors!) But, there’s a bigger, more corrosive problem, and I think it’s been destroying film

For a long time, my major problem with the fetishisation of auteur theory was that it wiped out the collaborative contributions of all these people whose collective intelligence makes a film so much better than any individual can on their own. (I haven’t even begun to talk about actors!) But, there’s a bigger, more corrosive problem, and I think it’s been destroying film.

*

“TV is so good right now.” It is, isn’t it? Quick two-part quiz:

- Who directed your ten favourite TV shows last year?

- Does that tell you anything about their principal creators?

Putting Twin Peaks: The Return to one side, I’m guessing most of these shows are made using traditional television production practices. A showrunner works with a writing room to break the story beats over a season, possibly in consultation with actors and producers. Then scripts are written by members of the writing room and directed by external directors, with the showrunner keeping an eye over everything. That’s how they’ve made every show from The Sopranos and Breaking Bad to Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and all points in between.

This production model is roughly 8765% better (author’s estimate) at harnessing collective intelligence than the traditional filmmaking model: guy writes screenplay alone, then as director finds people who can bring his vision to screen via micromanagement. That’s not to say that the television production model is always better – many of the things that people find most compelling about film are individual formal choices and expressions that are necessarily diluted in a collaborative environment – but its relative success against film over the past few years bears consideration.

Recently, some television shows have been harnessing the best of both worlds, using a series director and a strong writer to bring two strong voices to their show that work in tandem. True Detective creator Nic Pizzolatto brought in indie filmmaker Cary Fukunaga to direct season one, with electrifying results. (That Pizzolatto’s ego led to Fukunaga not returning for season two, and the subsequent audience reception of season two, gives a lovely case study to those who would like to ascertain the extent to which the success of season one was attributable to Pizzolatto’s writing or Fukunaga’s direction.) More recently, Big Little Lies combined showrunner David E. Kelley’s acerbic point of view with the swoony sensuality of director Jean-Marc Vallée (best known for Wild and Dallas Buyers’ Club). Whether Kelley will be able to strike gold again in season two (this time working not with Vallée but with Andrea Arnold, and having exhausted the source novel) remains to be seen.

One could go on for ages, with the profusion of television and Netflix, and filmed material that blurs the lines. (Is Errol Morris’s Wormwood, as recognisably auteurist a project as he’s ever done, a ‘movie’ or a ‘TV series’? What about OJ: Made In America? They’ve both played in movie theatres, after all, even though 99% of their audience saw them on TV.) The point is that in television – at least internationally (locally is a whole separate can of worms) – creative collaborations of all types are blooming, and everyone who likes watching good stuff is better off for it.

Meanwhile, people still want to be film directors.

*

I know it’s more than ego at play. It’s the burden of history

I guarantee you, if you go to film school, or if you make a 48 Hours film, or if you just decide to make a movie with your friends, the first, biggest, and possibly most resentment-stirring fight is about who will be the director. I’ve done all these things, and I’ve seen all those fights.

Often people say it’s about the ego, and I’m sure that’s true to a certain degree. We want something to be proud of, something we can put our name on. But as somebody who has eschewed a ‘film by’ credit on his feature (I hate them, unless you’ve literally made the film on your own, shut up, and yes, I do know their contractual history so yes, fine, you have to have them but that doesn’t mean I have to stomach them) I know it’s more than ego at play. It’s the burden of history.

Because films are supposed to have a director, and directors are supposed to be in charge – that’s how you think a film gets made – and you start shaping your collaborative methods around that received model. It means that you hear yourself saying things like, “Well, I’m the director, so this is what we’re doing.” It means that you close yourself off to ideas that are not your own.

It means you kind of become a terrible person, and moreover, you completely waste a significant portion of the collective intelligence that’s in the room with you. And you probably wind up with a worse film.

To be fair, even within a traditional power structure some directors are much greater at harnessing collective intelligence than others. For every Hitchcock-wannabe with meticulous storyboards begrudgingly illustrated with ‘meat props’ in order to execute their vision, there are lovely talented people who can put their egos to one side and let the best idea reign. (And there are also people who completely lose sight of the overarching vision in the flurry of ideas and inspiration on set, and come back with unusable footage, or a film that needs to be entirely reconceived because its script got lost in translation.)

In an industrial context, standardisation of roles has its place, and that’s why the structure persists in larger film productions. It’s reliable, it communicates everyone’s jobs well, and it’s optimised to best return a product that professionally meets the requirements of its investors.

If we let go of our grip on auteur theory, we’ll find there are countless other tools that we can use to advance our creative dreams to the next level

To which I say, great, and if you want to get into something that has high returns on investment, I hear biotech is doing well. But if you want to make awesome stuff in a collaborative medium, go collaborate. We live in an age where the tools of audiovisual storytelling are cheap, where you can endlessly prototype, revise, and shoot. We live in an age where a film like Waru is more vital than any of the traditionally structured dramas we’ve been churning out. If we let go of our grip on auteur theory, we’ll find there are countless other tools that we can use to advance our creative dreams to the next level.

Put down that hammer. Pick up a camera. Find some collaborators. And make something awesome.